Author:

To all of my readers, I wish you a very merry Christmas and a happy, healthy, and prosperous new year. I hope that 2012 is a better year for all of us.

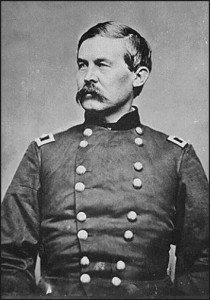

Scridb filter On December 16, 1863, the United States Army lost its best cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. John Buford, who died of typhoid fever in the rented house of his fellow horse soldier, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, in Washington, D.C. Buford’s dear friend Maj. Gen. John Gibbon once said that “John Buford was the finest cavalryman I ever saw.” He died in the arms of his staff officer and surrogate son, Capt. Myles W. Keogh (who later died with Custer at the Little Big Horn). The Union’s loss was enormous, almost unimaginable.

On December 16, 1863, the United States Army lost its best cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. John Buford, who died of typhoid fever in the rented house of his fellow horse soldier, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, in Washington, D.C. Buford’s dear friend Maj. Gen. John Gibbon once said that “John Buford was the finest cavalryman I ever saw.” He died in the arms of his staff officer and surrogate son, Capt. Myles W. Keogh (who later died with Custer at the Little Big Horn). The Union’s loss was enormous, almost unimaginable.

Buford was promoted to major general–a long overdue promotion that had long been sought on his behalf–on his deathbed the day he died. In a moment of lucidity, he said, “too late.” And sadly, it was. His final words, as befit the finest cavalryman in the army, were “Put guard on all the roads, and don’t let the men run back to the rear.”

This was the obituary of Buford that ran in the New York Times the next day:

Major-Gen. JOHN BUFORD, who died at Washington yesterday, was a graduate of the West Point Military Academy, and in the Regular army held the rank of Major in the Inspector-General’s Department. He was appointed Brigadier-General of Volunteers on the 27th of July, 1862, and assigned to the command of a cavalry brigade under Gen. POPE, in his Virginia campaign of that year. When that army was merged with the Army of the Potomac, Gen. BUFORD was assigned to the command of the regular cavalry brigade, which he held until the formation of the cavalry corps into three divisions, when he was placed in command of the First division, and served throughout the severe campaigns of the past ten months with the most distinguished gallantry. He was considered the best field cavalry commander in the service, and was noted for his coolness and judgment under fire. He was about forty years of age, of full habit a man of generous nature and warm impulses. Before his death the President rewarded him with the commission of Major-General. The country has lost a noble spirit and a brave defender.

The great cavalryman was buried in the post cemetery at West Point, where he rests under a handsome monument paid for the by the men of his First Cavalry Division.

The great cavalryman was buried in the post cemetery at West Point, where he rests under a handsome monument paid for the by the men of his First Cavalry Division.

As some of you may recall, in January of this year, I commenced an experiment. I purchased a black and white Nook with the intention of using it to download public domain regimental histories and the like from Google Books for use in my various projects. A little over a week later, and on the recommendation of Steve Stanley, I exchanged it for a Nook Color. I then began to experiment with it in the hope that I could make it work the way that I hoped to use it. The experiment proved to be terribly frustrating.

As some of you may recall, in January of this year, I commenced an experiment. I purchased a black and white Nook with the intention of using it to download public domain regimental histories and the like from Google Books for use in my various projects. A little over a week later, and on the recommendation of Steve Stanley, I exchanged it for a Nook Color. I then began to experiment with it in the hope that I could make it work the way that I hoped to use it. The experiment proved to be terribly frustrating.

I gave up on the experiment today. No matter what we tried, we were unable to make the thing work with …

The other day, I received this e-mail through this blog:

I am serching for info on the 6th georgia calv. company K My 3 great grandfather Andrew Jackson Brigman from walker co georgia was inlisted as a private on the confedrate side. I can find no info on this company, but have found sevral publications on genalogy sites regarding this very company, I am wondering what he did and where he fought. the family folk lore was that he had his 3 fingers shot off, in the war at some point. and was left for dead by the union troops.Or he played dead one or the other. I am wondering how to find this info if it is true. and as well why soon after the war did he move from walker county georgia where he had a plantation and family to lousiville Ky and then to Paducah, was he shipped to paducah because of wounds, Paducah is known for the union hospital sites but not confedrate? Ahh !!! Im so confused I need help if you can steer me in the right direction, Or give me a creditable web site I would be so greatful.

I get at least one inquiry like this per week. While I am flattered that you think I know enough about the war to answer questions about your specific ancestor, the very substantial likelihood is that I don’t. More likely than not, your ancestor served in a unit that I know nothing about. The 6th Georgia Cavalry, being a Western Theater unit, is not one that I know anything about. And while I appreciate your confidence in me and in your taking the time to write, if I did the research to answer every one of these inquiries, I would have no time to do anything else. Consequently, I made the decision that, unless it’s something I can answer in ten minutes of less, I will not do so, and that I will not typically respond to those inquiries for the simple reason that doing so takes time that I don’t have to spare.

I regret it if that offends the folks who make those inquiries, but I simply don’t have time. But I do thank you for your interest and for your faith that I might somehow be able to help. If I can, I will. If not, then the likelihood is that I will not respond.

Scridb filterThis evening, I have added a link to my friend Steve Cunningham’s excellent West Virginia in the Civil War website under the “Civil War Sites” category. Take a few minutes and check out Steve’s site, which is chock-full of good and useful information. You won’t be disappointed.

Scridb filterOn this Thanksgiving Day, when we all have to much to be thankful for, I want to share this, Brian Pohanka’s final interview, wherein he talks about the importance of battlefield preservation. It is haunting and bittersweet to see his image and to hear his voice again so many years after his untimely death, but it’s critical that we continue his work. I miss his wise counsel.

Here is a link to the interview.

And to all, a happy Thanksgiving. Be grateful for what you have. I know that I am. I am grateful to everyone who takes the time to visit this blog, and I am grateful to everyone who takes the time and spends their hard-earned money to read my books.

Scridb filterThe following neo-Confederate hooey was posted on Facebook today:

The legacy of Captain Henry Wirz should be rewritten. This man was a hero for doing the best he could. And, on his final night before his execution, Stanton sent govt agents to Wirz`s cell offering a bribe to for liberty if he implicated President Davis for Andersonvilles problems. Wirz stood strong to his values with integrity and chose death before excepting a bribe against Davis, even though he was completely innocent himself…..This is just another example how evil and devious Stanton really was to try and bribe Capt Wirz into lying against President Davis….God bless Captain Wirz, you were a hero for that act alone!

This is, of course, a mainstay of neo-Confederate doctrine. As it goes, Wirz was a hero and martyr, and only the wardens of Elmira and the other Union POW camps were war criminals. The heroic Wirz, by contrast, maintained his heroic character by refusing to implicate Jefferson Davis. So, therefore, his war crimes weren’t so bad. Ummmm…no.

As I said, this is a mainstay of neo-Confederate doctrine. Try this one on for size, which appears on a prominent neo-Confederate website, that of the Georgia Heritage Council:

A Confederate History Minute (9) – by Calvin E. Johnson, Jr.

Captain Henry Wirz, Confederate Hero and Martyr

Captain Henry Wirz was born, Hartman Heinrich Wirz in November 1823, in Zurich, Switzerland where his father, Abraham Wirz was highly respected.

At the outbreak of the War Between the States, Wirz enlisted in the Fourth Louisiana infantry on June 16, 1861. He was promoted to sergeant a year later and was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. He never recovered from the injury to his left wrist and it caused him great pain for the rest of his life.

Wirz was promoted to Captain on June 12, 1862 and was first detailed to General John Winder where he was given command of a Confederate military prison in Richmond, Virginia.

After serving a year as special emissary to President Jefferson Davis in Paris and Berlin, on March 27, 1864, he was installed as commandant of Andersonville Prison at Fort Sumter in Georgia. Wirz did the best he was able to do with many Union prisoners and the little food and medicine. It is written that the guards got the same food and medicine as the prisoners.

The Confederacy sent a distress message to Union President Abraham Lincoln and Union General Ulysses S. Grant. The South pleaded for an exchange of Confederate and Union prisoners. Lincoln and Grant, however, refused believing the Union prisoners might go home but the Confederate prisoners might go back to fight.

Captain Henry Wirz was unfairly charged of war crimes and it is written that no witnesses for the defense were allowed to testify. Among those who would have is a Union soldier who was a prisoner at the prison.

For over 30 years there have been efforts to exonerate the good name of Captain Henry Wirz. There is an annual memorial service to Wirz on the Sunday nearest November 10th each year in Andersonville, Georgia, at the monument to Wirz placed there by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (Georgia Division).

This sort of rewriting of history really is appalling. Wirz was hanged for a reason. He was neither a hero nor a martyr. He was a war criminal. Casting him in any other light is just plain wrong, and is something we need to remain constantly vigilant in battling. Call these neo-Confederate revisionists on their nonsensical hooey. Don’t let them get away with it.

Scridb filter The following inquiry appeared on some forum boards:

The following inquiry appeared on some forum boards:

What is the reasoning behind most historians today not willing to accept that Stuart’s attack was in cooperation with Pickett’s attack ? Now I have heard that one reason was because neither Stuart nor Lee made mention of it in their Gettysburg Battle reports. They also did not make mention of the signal shots but most historians think they happened, but not as signal shots.

The reason I am bringing this up again is due to the more research I do the more sources I find that state that Stuart was acting in cooperation with Pickett’s attack. Even the Union General in charge in the East Cavalry fighting, General D.McM.Gregg in an article states that it was. I have so far found 10 different sources that back’s this claim up. I just can’t accept it when historians say there is no evidence that Stuart was in cooperation with the frontal attack on Cemetery Ridge on July 3rd, 1863. As I have stated I have 10 different sources so far.

There actually is a rather simple explanation to all of this.

Let’s remember that late in the day on July 2, 1863, there were two separate but simultaneous engagements involving two separate divisions of Union cavalry on or near the far left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia’s position. David M. Gregg’s Second Division was engaged with Confederate infantry of the Stonewall Brigade of Maj. Gen. Edward “Alleghany” Johnson’s Division on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge, while Judson Kilpatrick’s Third Division tangled with troopers of Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Brigade at Hunterstown.

Brinkerhoff’s Ridge is squarely on the far left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia’s infantry position. The Stonewall Brigade ended up performing flank duty because of the breakdown of command after Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins was severely wounded that morning, and nobody thought to tell Col. Milton J. Ferguson, Jenkins’ senior colonel, that he was now in command of the brigade. Because of that inexplicable breakdown, Jenkins’ men failed to perform the flank duty. That forced the Stonewall Brigade to do so, keeping it tied up for most of the day and leaving it unavailable to assault Culp’s Hill. Stuart himself sat on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge and watched the climax of that fight. He knew that the Stonewall Brigade was fighting dismounted Union cavalry there. He could see Gregg’s guidons.

Just a few miles away at Hunterstown, Kilpatrick’s division tangled with the rearguard of Hampton’s Brigade, which was escorting the tail-end of the infamous wagon train captured by Stuart during his ride to the Gettysburg battlefield. A short but very spirited fight occurred there before both sides broke off.

Therefore, as the sun set late in the afternoon of July 2, there were a total of four brigades of veteran Union cavalry operating in the vicinity of Lee’s flank and rear, well positioned for a possible dash around the flank and into Lee’s rear, where they could make immense trouble.

Hence, on the night of July 2, Robert E. Lee knew that two of the three divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps were operating on or near his far right flank. He was legitimately concerned that the Federals might try to dash around that flank and make mischief in his rear. He was so concerned, in fact, that he called Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden’s Northwestern Brigade–a command that Lee did not know or particularly trust, largely because it was untried–to the battlefield. The following are Imboden’s own words, from an 1871 article that appeared in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: “on arriving near Gettysburg about noon, when the conflict was raging in all its fury, I reported directly to General Lee for orders, and was assigned a position to aid in repelling any cavalry demonstration that might occur on his flanks or rear. None being made, my little force took no part in the battle. I then had only about 2,100 effective mounted men and a six-gun battery.” (emphasis added by me)

Lee was concerned enough about this situation that he placed Imboden’s command in a position where it could quickly and readily deal with a thrust at the flank or into his rear.

By contrast, there was no known force of Union cavalry operating on Lee’s far right. In fact, Brig. Gen. John Buford’s First Division had left the field about 11:15 on the morning of July 2, and no cavalry troops (other than a single regiment of Gregg’s division) had been sent to take its place. Thus, as morning broke on July 3, there was absolutely no cavalry threatening Lee’s far right, as neither Wesley Merritt’s Reserve Brigade nor Elon J. Farnsworth’s brigade of Kilpatrick’s division arrived in the vicinity of the Confederate far right flank until about 11:00 in the morning of July 3. Consequently, the small force of 100 or so troopers of the 1st South Carolina Cavalry, with a single piece of horse artillery, was more than sufficient, as there was no known threat.

As J. D. Petruzzi and I have documented extensively in our book Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg, both Stuart’s men and horses had just finished a grueling eight day expedition around the Army of the Potomac that took a tremendous toll on both men and horses. Indeed, both men and mounts were at the limits of their endurance when they arrived on the battlefield very late in the afternoon of July 2, and neither men nor animals were in condition to undertake or engage in aggressive offensive activity, something that is well-documented. Therefore, the only mission for these troopers that makes any sense, given their worn-out condition, is a purely defensive one.

Given those circumstances, does it make nothing but sense for Lee to send Stuart and his three and a half brigades (about half of Jenkins’ brigade went with Stuart) to hold and protect that flank? So that there would be a significant force under his trusted and beloved cavalry commander, should that two-division threat to the flank and rear develop?

When analyzing all of these factors, and given Stuart’s dispositions and deployments on what became East Cavalry Field, it seems quite obvious to me that Stuart’s primary mission was to guard the flank. He deployed in an ambush formation, intended to draw David M. Gregg’s troopers in and engage them, thereby keeping them tied up and unable to make that dash around the flank. Stuart, always the opportunist, was looking for opportunities, and should he be able to defeat and scatter Gregg’s troopers, then, and ONLY then, would he attempt to make his own dash down the Low Dutch Road and into the rear of the Army of the Potomac’s position.

Finally, neither Lee nor Stuart EVER said anything about Stuart’s activities that day being somehow coordinated with the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble assault on the Union center. That, to me, is proof positive that neither officer contemplated anything other than what they both said in the official reports.

If you have studied the engagement on East Cavalry Field, and you know both the terrain and the condition of Stuart’s command, the battle plan that I have laid out above is ONLY explanation of Stuart’s mission on July 3 that makes any sense.

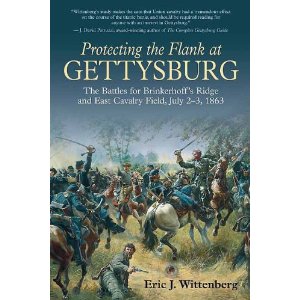

This essay is a synopsis of a small part of the 5500 word essay that I have written to rebut the ridiculous and implausible theory of Tom Carhart for the new edition of my book Protecting the Flank that will be published by Savas-Beatie in the early spring of 2012.

Scridb filterShameless self-promotion, November 16 edition: My NEW book, The Battle of White Sulphur Springs: Averell Fails to Secure West Virginia, is now out! This is the first and only detailed tactical study of this strategically important battle. It features the great maps of Steven Stanley and I am really excited about it. For those who have already ordered, you orders will ship on Saturday. If anyone is interested, please contact me!

Scridb filterMy friend Mike Block used to be a member of the board of trustees of the Brandy Station Foundation. Mike resigned that position in protest over the complete abrogation of the BSF’s duties as stewards of the battlefield. He has now posted his version of these events on his blog, and for those interested in this issue, it’s riveting but appalling reading.

A few thoughts, in no particular order:

1. Joseph McKinney was receiving flak from you, the readers of this blog, about his inactivity regarding this disaster. That pressure not only did not impact him or the board’s decision-making, it seems to have encouraged him to go the other way. He even mocks Bud Hall’s quite accurate description of this problem as “an unmitigated disaster.”

2. McKinney expressly admits that he failed to show leadership in this crisis, and, in fact, stated quite clearly that he didn’t want to spend much time on the greatest crisis faced by this battlefield since the development threats that led to the original land acquisitions.

3. From McKinney’s own words it is quite clear that they view this whole fiasco as nothing but a public opinion problem that needs to be quieted and dealt with and not as a preservation crisis. In other words, the spin is more important than doing their duty as stewards of the land. I find that absolutely incomprehensible and appalling all at the same time.

4. All of this makes it abundantly clear that neither the BSF board nor Joseph McKinney care a whit about preserving this battlefield, and that they have no business being at the helm of the organization tasked with preserving this hallowed ground.

Resign. Now.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like