Month:

December, 2012

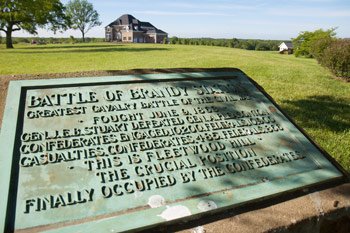

The Brandy Station Foundation has finally issued a statement about the purchase contract for Fleetwood Hill:

MAJOR NEWS: CIVIL WAR TRUST TO BUY FLEETWOOD HILL

It is my pleasure to inform you that on December 19, the Civil War Trust and Mr. Joseph A. Troilo, Jr., reached agreement for the Trust to purchase Tony Troilo’s fifty-seven acre property at the southern end of Fleetwood Hill. A link to an article from the December 21 edition of the Culpeper Star-Exponent is:

http://www.dailyprogress.com/starexponent/news/local_news/article_8eb4f41c-4af0-11e2-a40e-001a4bcf6878.html.

This agreement is the culmination of more than twenty years preservation efforts in Culpeper County. However, major work remains: now the Trust must raise $3.6 million to pay for the property. We encourage you to support the Trust with your generous donations. Also, as you know, we are holding a ball at the Inn at Kelly’s Ford on the evening of March 16, 2013, to commemorate the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. We will donate one-half of the proceeds from the ball to the Trust. So, come to the ball, have a good time, and help pay for Fleetwood Hill.

Joseph McKinney

President, Brandy Station Foundation

Let’s not break our arms patting ourselves on the back, shall we?

Let’s remember that this is the same organization that stood by and did NOTHING when Troilo started digging his recreational lake, even though McKinney had advance knowledge that he was going to do so. Let’s remember that this is the same organization that issued a statement saying that it’s okay if a local landowner wants to dig up the battlefield for his or her own purposes. And most importantly, this is the same organization that sat on its hands and did NOTHING for months while this critical parcel of land was listed for sale with a realtor. It did NOTHING to arrange for the land to be appraised, and it did NOTHING to negotiate a deal with the Civil War Trust.

In short, the BSF has once again proved the truth of what I’ve been saying here all along: the current, incompetent leadership of the BSF is not interested in battlefield preservation, and its incompetent leadership has rendered the organization entirely irrelevant.

So, while I applaud Useless Joe McKinney and the Board of Appeasers for getting on the train once it had already left the station, the fact that it wasn’t the original passenger on the train is what I find terribly troubling. You should too.

Scridb filter This past spring, I was asked to write a short article (about 1000 words) on horses in the Civil War for The History Channel Magazine. I had less than a week to do so, but I got it done. It was supposed to appear in the January/February 2013 issue, but there has been a regime change at the magazine, and the new editorial staff decided not to use any of the articles that it had in the hopper, including my article. Lest it go to waste, I’ve decided to run it here. Enjoy.

This past spring, I was asked to write a short article (about 1000 words) on horses in the Civil War for The History Channel Magazine. I had less than a week to do so, but I got it done. It was supposed to appear in the January/February 2013 issue, but there has been a regime change at the magazine, and the new editorial staff decided not to use any of the articles that it had in the hopper, including my article. Lest it go to waste, I’ve decided to run it here. Enjoy.

The photo is of U.S. Grant’s three horses, Egypt (on the left), Cincinnati (in the center) and Jeff Davis (on the right), taken at Cold Harbor, Virginia in the spring of 1864.

THE LOYAL STEEDS: HORSES IN THE CIVIL WAR

By: Eric J. WittenbergDuring the era of the Civil War, 1861-1865, there were no internal combustion engines fueled by gasoline, so there were only three ways to transport men, equipment and supplies: by boat, by train, or by horse. Horses were the primary means for logistics. Horses were used by artillery, by cavalry, by infantry, and by teamsters to move men and equipment. When the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, there were approximately 3.4 million horses in the Northern states, and 1.7 million in the Confederate states. The border states of Missouri and Kentucky had an additional 800,000 horses. During the Civil War, the Union used over 825,000 horses for the purposes described above.

More than 1,000,000 horses and mules were killed during the Civil War. In the early days of the conflict, more horses than men were killed. Just at the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg alone, the number of horses killed was about 1,500—881 horses and mules for the Union, and 619 for the Confederacy. The toll taken on these loyal animals—upon which both sides relied heavily—was staggering, and is all too often overlooked.

Napoleon once wrote, quite correctly, that “an army moves on its stomach,” meaning that logistics are the key to the success of an army in the field. The great Union general, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, understood this well, prompting him to write, “Every opportunity at a halt during a march should be taken advantage of to cut grass, wheat, or oats and extraordinary care be taken of the horses upon which everything depends.”

The artillery relied heavily on horses, which were the primary means of moving heavy cannons from place to place. In so-called “mounted artillery”, which typically served with the infantry, the men who served those cannons either walked or rode on the caissons or limber chests, while horses and mules pulled the guns. The horses involved were usually big draft animals that were capable of bearing heavy weights. Maj. Gen. John Gibbon, who wrote the standard treatise for artillerists in the Civil War, The Artillerist’s Manual, described the ideal artillery horse:

The horse for artillery service should be from fifteen to sixteen hands high … should stand erect on his legs, be strongly built, but free in his movements; his shoulders should be large enough to give support to the collar but not too heavy; his body full, but not too long; the sides well rounded; the limbs solid with rather strong shanks, and the feet in good condition. To these qualities he should unite, as much as possible, the qualities of the saddle horse; should trot and gallop easily, have even gaits and not be skittish.

When artillery served with cavalry, it was called horse artillery, and each man had his own horse, so that the artillery could keep pace with fast-moving cavalry.

Draft animals also served to move the army’s vast wagon trains of supplies. Typically six horses or mules drew each wagon, which could be full of supplies, personal baggage, or medical supplies. Draft animals and mules also pulled ambulances, which carried wounded men from battlefields. As just one example, after the Battle of Gettysburg, a seventeen-mile long wagon train of wounded men was needed to remove the most seriously injured Confederate soldiers from the battlefield. But for the horses and mules that made it possible, these men probably would not have made it back to safety.

The most obvious use of horses in the Civil War was to carry cavalry. Cavalry featured mounted men who used their horses to move from place to place, and who could fight either mounted or dismounted. A cavalryman and his horse became a team, and men often developed deep bonds with their horses. Those horses often faced stern tasks.

Capt. George Baylor of the 12th Virginia Cavalry left this description of that close bond:

The cavalryman and his horse got very close to each other, not only physically, but also heart to heart. They ate together, slept together, marched, fought and often died together. While the rider slept, the horse cropped the grass around him and got as close up to his rider’s body as he could get. The loyal steed pushed the trooper’s head gently aside with his nose to get at the grass beneath it. By the thousands, men reposed in fields fast asleep from arduous campaigns with their horses quietly grazing beside them, and nary a cavalier was trod upon or injured by his steed.

They were so faithful and unfaltering. When the bugle sounded, they were always ready to respond, for they knew all the bugle calls. If it were saddle up, or the feed, or the water call, they were as ready to answer one as the other. And they were so noble and so brave in battle. They seemed to love the sound of the guns. The cavalryman might lie low on the neck of his horse as the missiles of death hissed about him. But the horse never flinched, except when struck.

Lo! As we should, we build monuments for our dead soldiers, for those we know, and for the unknown dead. So with the ultimate sacrifice of our lamented fallen honored upon their noble deaths, is it not also just that we recall their valiant steeds? What would you think of a monument some day, somewhere in Virginia, in honor of Lee’s noble horses?

Without the horse, there could be no cavalryman.

The lore of the Civil War is replete with famous horses. Confederate commander Gen. Robert E. Lee had his beloved Traveler. Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson had his Little Sorrel. Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, who made a legendary 22-mile dash from Winchester to the battlefield at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, rode his warhorse Rienzi. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had his Cincinnati. Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest had his King Philip, and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the victor at Gettysburg, had his Old Baldy. These famous mounts carried their masters into battle and into legend.

In some ways, the horses that suffered and died during the Civil War were more important than the men who rode them. The Union certainly could not have prevailed in the Civil War without the horses that it relied upon so heavily.

As a student of cavalry operations, I’ve come to understand that a cavalryman is effectively two indivisible parts: man and horse. As stated above, without the horse, there could be no cavalryman. In many instances, the loyal horses did their duty until the could do more, collapsed and died. And for the cavalryman, it was akin to losing his best friend. The photo is of the cavalry horse monument in Middleburg, Virginia. It depicts a played out horse, weary and worn to a nub, still doing his duty.

As a student of cavalry operations, I’ve come to understand that a cavalryman is effectively two indivisible parts: man and horse. As stated above, without the horse, there could be no cavalryman. In many instances, the loyal horses did their duty until the could do more, collapsed and died. And for the cavalryman, it was akin to losing his best friend. The photo is of the cavalry horse monument in Middleburg, Virginia. It depicts a played out horse, weary and worn to a nub, still doing his duty.

It’s easy to forget about the sacrifices of the loyal steeds during the Civil War, and I hope that this brief article helps people to remember those sacrifices.

Scridb filterTo each and every one of you who takes the time to indulge my rantings, Susan, Nero, Aurora, Jet, and I all wish each and every one of you a joyous holiday season, a merry Christmas, and a happy, healthy, and prosperous 2013. Personally, I will not miss 2012 in the least, and can only hope that 2013 is a better year for all of us.

Thank you for indulging me. I appreciate all of you.

And for those who are traveling: please be safe. There’s a big winter storm coming, so please exercise caution as you travel to see your loved ones.

Scridb filterToday’s issue of the Culpeper Star-Exponent contains an article about the purchase contract to save Fleetwood Hill that I discussed here yesterday. That article contains a statement by Tony Troilo that I find really perplexing: “[Troilo] credited Brandy Station Foundation President Joe McKinney as being instrumental to the sale. ‘He kept the CWPT in the mix,’ Troilo said.”

Those of us who make up the board in exile of the Brandy Station Foundation have been in constant communication with Bud Hall about this. And Bud has been in constant communication with the Civil War Trust about this, and NOBODY has said a word about either the BSF or Useless Joe McKinney and his Board of Appeasers doing anything whatsoever about this. Indeed, this happened in spite of Useless Joe and his useless gang, not because of anything that they did. Indeed, when you do nothing, it’s hard to claim credit for doing something.

And so, I ask: What did you do, Useless Joe? What role did you play in preserving Fleetwood Hill? Pray tell. We would all like to know.

For the record, I would like nothing more than to be proved wrong, and if Useless Joe and the Board of Appeasers demonstrate to me that I am wrong, then I will gladly apologize. However, knowing what I know about this situation, I am not the least bit concerned about having to do so….

UPDATE, DECEMBER 24, 2012: As of today, there has not been even so much as a mention of the contract for the preservation of Fleetwood Hill on the Brandy Station Foundation’s website. This is, perhaps, the single most important land preservation deal yet signed, and certainly is the key acquisition of the Brandy Station battlefield. One would think that the BSF, allegedly the steward of the battlefield, would say something about such a critical transaction, but there is nary a word. This is yet more evidence of the fact that this organization is NOT interested in battlefield preservation. Either lead, follow, or step aside, Useless Joe and the Board of Appeasers.

Scridb filterI am just thrilled to share with you the press release issued by the  Civil War Trust earlier today:

Civil War Trust earlier today:

Civil War Trust Announces Preservation Opportunity at Fleetwood Hill on Brandy Station Battlefield

NEW OPPORTUNITY EMERGES JUST AS ORGANIZATION ANNOUNCES SUCCESSFUL COMPLETION OF CAMPAIGN TO PRESERVE 964 HISTORIC ACRES AT NEARBY KELLY’S FORD

(Culpeper, Va.) – The Civil War Trust, America’s largest nonprofit battlefield preservation group, today announced the that it has secured a contract with a Culpeper County landowner to acquire 61 acres of core battlefield land at Fleetwood Hill on the Brandy Station Battlefield. This is the first step in what is anticipated to be a national fundraising campaign to ultimately preserve this site and open it to the public. This opportunity comes just a few months before 150th anniversary commemoration of the battle, fought on June 9, 1863.

“The Civil War Trust is pleased to confirm that we have reached an agreement with a local landowner to place under contract his 61-acre property on Fleetwood Hill,” noted Civil War Trust President James Lighthizer in a statement released earlier today. “Protection of this property at the epicenter of the Brandy Station battlefield has been a goal of the preservation community for more than three decades.”

Although pleased with the agreement, Lighthizer cautioned that “several steps remain before the transaction is completed and the property can be considered preserved — chief among them raising the $3.6 million necessary to formally purchase the land.” He noted the Civil War Trust’s intention “to launch a national fundraising campaign next year with the aim of raising the money in time for the 150th anniversary of the battle in June 2013. Further details of this exciting opportunity — including mechanisms for public involvement and donations — will be announced in the new year, once additional groundwork for the project is laid.

Brandy Station, with nearly 20,000 troopers in blue and gray engaged in the struggle, was the largest cavalry battle ever fought on American soil. More than 1,000 men became casualties as a result of the battle. Although a Confederate victory, Brandy Station is often referred to as the battle where the Union cavalry came into its own after years of being dominated by Southern horse soldiers. The epicenter of fighting at Brandy Station took place on the slopes of Fleetwood Hill, described by historian Clark B. “Bud” Hall, as “without question the most fought over, camped upon and marched over real estate in the entire United States.”

“I truly believe that this acquisition, if successful, will be the most important battlefield preservation achievement not just at Brandy Station, but in all of Virginia’s Piedmont, a region that was of immense military and strategic significance during the Civil War,” remarked Hall. “Although it most closely associated with the climactic fighting of June 9, 1863, there were, in fact, 21 separate military actions on Fleetwood Hill during the Civil War—far more than any other battle venue in this country.”

The Civil War Trust has long been committed to ensuring the protection and appreciation of the battlefields in Culpeper County, Virginia. To date, we have helped protect nearly 1,800 acres at Brandy Station — more land than at any other individual battlefield in the nation

In the 1990s, Brandy Station was also the scene of a high-profile preservation battle. At one point, 1,500 acres of the battlefield were rezoned to allow for light industrial development. Later, a 515-acre Formula One auto racetrack was proposed for the site. However, due to the persistence of preservationists throughout the country, plans to develop the battlefield were thwarted. Today, the Civil War Trust owns 878 acres of the Brandy Station Battlefield that are open to the public; interpretation of the site includes educational signage, walking trails and a driving tour.

The Civil War Trust has been also been actively involved in preserving land at other battlefields in Culpeper County. This summer, on its 150th anniversary, the Trust announced an effort to preserve an additional 10 acres on the Cedar Mountain Battlefield. More recently, the Trust completed a national fundraising campaign to place a perpetual conservation easement on 964 acres at Kelly’s Ford, site of the war’s first large-scale cavalry engagement. These transactions were made possible through the generosity of Trust members and the financial support of matching grants from the American Battlefield Protection Program, administered by the National Park Service, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and the Virginia Department of Transportation.

Learn more about the Battle of Brandy Station at www.civilwar.org/brandystation.

The Civil War Trust is the largest nonprofit battlefield preservation organization in the United States. Its mission is to preserve our nation’s endangered Civil War battlefields and to promote appreciation of these hallowed grounds. To date, the Trust has preserved more than 34,000 acres of battlefield land in 20 states, and nearly 3,000 on important Culpeper County battlefields like Brandy Station, Cedar Mountain, and Kelly’s Ford. Learn more at www.civilwar.org, the home of the sesquicentennial.

I congratulate Tony Troilo for doing the right thing. And I congratulate the good folks at the Civil War Trust for their diligence and dedication to making this happen. But most of all, I congratulate Clark B. “Bud” Hall for making this happen. This–the capstone of Bud’s preservation career–would not have happened without his zealous advocacy, leadership of the “board in exile” of the Brandy Station Foundation, and for his dogged perseverance with the Trust to ensure that this deal got done.

We’re only part of the way there, though.

The heavy lifting must now be done. We have $3.6 million to raise. Every one of you who regularly reads this blog and has asked me what you could do to help–the time is now for you to open your checkbook and help us to raise the money. This opportunity will never come around again, and we must do all we can to make this happen now. Please contribute whatever you can to help to save the single most fought over piece of ground on the North American continent. Beside being fought over in four major engagements, this parcel also housed Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s headquarters, Army of the Potomac, for the army’s winter encampment in 1863-1864. You would be hard-pressed to identify a more important parcel of unprotected ground anywhere in this great land of ours, and I encourage each and every one of you to do what you can to help.

And think how much fun it will be to see that hideous McMansion come down when the time comes! 🙂

Scridb filterAfter all of the horror of the events in Connecticut last week, I thought it might be fun to lighten things up a bit.

With thanks to my friend Dan Mallock, the party responsible for this idea, we’re going to discuss the ugliest/worst Civil War monuments in America. Specifically, I want everyone to chime in and let me know which you think is the ugliest/worst Civil War monument that you’ve ever seen. I will gladly post photos if anyone wants me to do so. Just send them along.

Here’s my nominee: the Nathan Bedford Forrest action figure along I-65 in Brentwood, Tennessee. This is, without doubt, THE most hideous, stupid-looking thing I have ever seen. It’s a horror.

Here’s my nominee: the Nathan Bedford Forrest action figure along I-65 in Brentwood, Tennessee. This is, without doubt, THE most hideous, stupid-looking thing I have ever seen. It’s a horror.

Dan, on the other hand, believes that the James Longstreet carousel horse monument wins the prize. It’s definitely my second choice, and it’s really pretty horrific too. From my perspective, however, it cannot hold a candle to just how horrendous that Forrest action figure is.

Dan, on the other hand, believes that the James Longstreet carousel horse monument wins the prize. It’s definitely my second choice, and it’s really pretty horrific too. From my perspective, however, it cannot hold a candle to just how horrendous that Forrest action figure is.

So, those are the first two entries in the competition. What do the rest of you think?

UPDATE, DECEMBER 21: Since it was nominated by Brian, here is the Stonewall Schwarzenegger statue on Henry House Hill on the Bull Run battlefield.

One of the things that I have always loved about this blog is that it gives me a venue to try out some ideas/theories here before doing anything further with them. If people laugh, then that’s the end of it. However, if people say, “hey, there’s something to that”, then it’s worth taking it a step further. This post is one of those experiments. Let’s see how it goes.

By way of introduction, back in October, I was the keynote speaker at Ohio Day at Antietam. I did a talk on the role played by Ohio troops in the Battle of Antietam. In the process of researching it, I realized that there is no book on the subject to be found anywhere other than the book published by the Ohio Monuments Commission pertaining to the monuments to Ohio troops erected at Antietam, so I decided to do a book on the subject. My project actually covers Ohio troops in the entire 1862 Maryland Campaign, meaning that it covers the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam, and the Ohio troops (three regiments and two brigade commanders) involved in the Harpers Ferry debacle. There are four parts to the book: the units and the roles they played, the roles played by the two future presidents of the United States (Hayes and McKinley), profiles of other prominent Ohio officers (including Ohio-born Confederate Brig. Gen. Roswell S. Ripley) in the campaign, including profiles of the regimental commanders (two of whom were killed in the fighting on the Otto Farm or at Burnside’s Bridge), and finally, the three Medal of Honor recipients from Ohio. The book will be titled Buckeyes Forward: Ohio Troops in the 1862 Maryland Campaign. It will feature lots of maps and photos and should appeal to the general public, which is the intended audience.

One of the prominent commanders profiled is George B. McClellan. While a native Philadelphian, Little Mac was living in Cincinnati when war came, and his initial commission as an officer during the Civil War was by Ohio Gov. William Dennison, who placed him in command of all of Ohio’s troops. McClellan’s initial campaigns in West Virginia primarily involved Ohio troops, so it’s a legitimate connection. McClellan is, of course, a terribly controversial fellow. Stephen Sears has made a career of vilifying McClellan, to the point of being unfair about it. Ethan Rafuse has written a very balanced and fair study of McClellan’s role in the Civil War that I believe is probably the definitive word on the subject.

One of the prominent commanders profiled is George B. McClellan. While a native Philadelphian, Little Mac was living in Cincinnati when war came, and his initial commission as an officer during the Civil War was by Ohio Gov. William Dennison, who placed him in command of all of Ohio’s troops. McClellan’s initial campaigns in West Virginia primarily involved Ohio troops, so it’s a legitimate connection. McClellan is, of course, a terribly controversial fellow. Stephen Sears has made a career of vilifying McClellan, to the point of being unfair about it. Ethan Rafuse has written a very balanced and fair study of McClellan’s role in the Civil War that I believe is probably the definitive word on the subject.

As I was assessing Little Mac’s career with the Army of the Potomac, I was suddenly struck by its similarities to the career of Douglas MacArthur. Specifically, I was struck by the problems that both generals had with their commanders in chief, which problems led to the ends of both of their careers commanding troops in the field. Let’s explore those parallels a bit.

George B. McClellan was a Democrat who believed that the Civil War was primarily about preserving the Union, and not about abolishing slavery. He did not believe in total war, and tended to be cautious and conservative. He served under an administration of the other party, meaning that many of his political beliefs were squarely at odds with those of the Commander-in-Chief. There is no doubt that McClellan disdained Lincoln, and made a poor decision by snubbing the President of the United States in November 1861 by making Lincoln wait for half an hour when Lincoln called upon him. Their relationship only went downhill from there. McClellan’s letters to his wife Ellen, which were not intended to be read by the public, were extremely insulting of Lincoln, calling him a baboon and other such unflattering names. The posthumous publication of these letters has undoubtedly tainted the perceptions of McClellan of many modern historians, which is unfortunate.

In a draft of his memoirs, McClellan made the following statement, which does not appear in the final version of the book, which perhaps describes his military career better than any other statement I have yet read: “It has always been my opinion that the true course in conducting military operations, is to make no movement until the preparations are as complete as circumstances permit, & never to fight a battle without some definite object worth the probable loss.”

Sears, who is not only Little Mac’s harshest critic but also the leader of the anti-McClellan movement, says of him:

There is indeed ample evidence that the terrible stresses of commanding men in battle, especially the beloved men of his beloved Army of the Potomac, left his moral courage in tatters. Under the pressure of his ultimate soldier’s responsibility, the will to command deserted him. Glendale and Malvern Hill found him at the peak of his anguish during the Seven Days, and he fled those fields to escape the responsibility. At Antietam, where there was nowhere for him to flee to, he fell into a paralysis of indecision. Seen from a longer perspective, General McClellan could be both comfortable and successful performing as executive officer, and also, if somewhat less successfully, as grand strategist; as battlefield commander, however, he was simply in the wrong profession.

At the same time, when asked who was his ablest foe during the Civil War, Robert E. Lee declared, “McClellan, by all odds!” Certainly, Lee’s opinion counts. McClellan had some real talents. He was an outstanding organization and trainer of men; the Army of the Potomac as we know it is largely the result of his efforts. He was an outstanding strategist and an able tactician. He had a really rare gift for motivating men and for earning their love and trust; just the rumor that he was returning to take command of the Army of the Potomac in the days just before the Battle of Gettysburg had a genuinely electric impact on the men in the ranks, who loved him dearly.

However, there can be little doubt or dispute that the following statements are true:

McClellan was a child of privilege who achieved great accomplishments at a precocious age; he became general-in-chief of the Union armies at the age of just 36. He had an oversized ego that seems to have gotten in the way of his making good decisions for his career path. He graduated at the top of his West Point class and had the support of high-ranking officers (such as Winfield Scott) who helped advance his career path. He was a Democrat whose personal political beliefs and philosophies were at odds with those of the Republican President. He disagreed with Lincoln’s decision to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in the wake of McClellan’s close victory at Antietam, and McClellan did not keep his displeasure with this political decision to himself. Indeed, there were times where McClellan was plainly insubordinate of Lincoln. His refusal to comply with the orders of the Commander in Chief led directly to his dismissal as commander of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, 1862. He never led troops in the field again, and he ran for President on a peace platform that was diametrically opposed to the policies of the Lincoln Administration.

The parallels with MacArthur’s life and career in numerous ways are striking.

Douglas MacArthur was also a child of privilege. His mother came from a prominent Virginia family, and his father was a Medal of Honor recipient who achieved the rank of lieutenant general in the United States Army (in fact, Arthur MacArthur and Douglas MacArthur are one of only two father-son combinations to be awarded the Medal of Honor). MacArthur graduated first in his class at West Point, and was fortunate to be appointed to serve on his father’s staff early in his career. He performed outstanding service in World War I, and received rapid promotions as a result. In 1925, at the very young age of 44, he became the Army’s youngest major general, and eventually became its youngest chief of staff.

Douglas MacArthur was also a child of privilege. His mother came from a prominent Virginia family, and his father was a Medal of Honor recipient who achieved the rank of lieutenant general in the United States Army (in fact, Arthur MacArthur and Douglas MacArthur are one of only two father-son combinations to be awarded the Medal of Honor). MacArthur graduated first in his class at West Point, and was fortunate to be appointed to serve on his father’s staff early in his career. He performed outstanding service in World War I, and received rapid promotions as a result. In 1925, at the very young age of 44, he became the Army’s youngest major general, and eventually became its youngest chief of staff.

During World War II, MacArthur became Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in the Pacific Theater of Operations, and is one of only a handful of men to wear the five stars of a General of the Armies. He developed the strategy that won the war in the Pacific and deserves recognition for being an able strategist. He eventually became the military governor of Japan after the end of World War II and is rightfully credited as one of the architects of the robust parliamentary democracy that succeeded the militaristic imperial regime that brought about World War II.

When war broke out on the Korean Peninsula, MacArthur was the first commander of the U.N. troops sent there, and his refusal to obey the orders of President Harry S. Truman led to his being relieved of command and ordered to return home to the United States. MacArthur never commanded troops in the field again. He was given the honor of addressing Congress, and gave a legendary speech that included the oft-quoted line, “I am closing my 52 years of military service. When I joined the Army, even before the turn of the century, it was the fulfillment of all of my boyish hopes and dreams. The world has turned over many times since I took the oath on the plain at West Point, and the hopes and dreams have long since vanished, but I still remember the refrain of one of the most popular barrack ballads of that day which proclaimed most proudly that “old soldiers never die; they just fade away. And like the old soldier of that ballad, I now close my military career and just fade away, an old soldier who tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty. Good Bye.” MacArthur, a conservative Republican, toyed with running for President, but ultimately decided not to do so, clearing the way for the nomination of Dwight D. Eisenhower, who served two terms as President of the United States.

Let’s recap: MacArthur was a child of privilege who accomplished great things at a young age, including becoming chief of staff of the Army. He had an immense ego that was often the subject of jokes and disdain, and which got in the way of his military career. He graduated at the top of his West Point class, and had the support of high ranking officers in important positions that allowed his career to thrive early on. He was a conservative Republican whose political views ran counter to those of Democratic President Harry S. Truman that brought him into open conflict with the commander-in-chief of the United States. His refusal to obey a direct order of that commander-in-chief led to his relief from command of the armies, and he never commanded troops in the field again. He toyed with running for President on a platform that would have been diametrically opposed to many of the policies of the Truman Administration.

Like McClellan, MacArthur is not remembered as a great battlefield commander. Instead, his defeat in the Philippines in the early days of World War II is, perhaps, the most crushing defeat ever suffered by the United States of America. The fact that the most renowned biography of him is titled American Caesar speaks volumes for the nature of his personality and of his legacy. Like McClellan, MacArthur is not fondly remembered or considered to be one of the greats of American military history.

I wonder what you all think of this comparison. I just found the similarities and parallels striking. Please feel free to weigh in.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like