Author:

The following article, by a correspondent embedded with the Army of the Cumberland’s Cavalry Corps, appeared on page four of the July 8, 1863 issue of The New York Herald. The entire issue is fascinating, as it covers the fall of Vicksburg, the retreat from Gettysburg, and Tullahoma. Nearly all of page four is devoted to the Tullahoma Campaign, which is often overlooked as compared to the other two campaigns.

MR. E.D. WESTFALL’S DESPATCHES

Headquarters, Reserve Corps

Army of the Cumberland

Shelbyville, Tenn., June 28, 1863

CAVALRY OPERATIONS

The corps of reliable gentlemen have been under a cloud since the movement of the army commenced, left Tuesday. I dislike to acknowledge that all my efforts to enlighten Herald readers in regard to movements on the right have proved futile, but they have this far. A special order denies us the use of the telegraph, and minute hairsplitting about “passes” prevents employment of messengers. However, things have assumed such shape today that I venture to tell how Stanley’s cavalry–temporarily under Gordon Granger’s command–came into possession of this stiff little Union burg. God prosper, henceforward, every loyal man in it. They have suffered enough.

OUR START AND PROGRESS

The “reserve corps,” with General R. B. Mitchell’s cavalry division, moved from Triune on Tuesday morning; the infantry eastward, on the old Murfreesboro road, the cavalry southward, on the Eaglesville pike, directly through the enemy’s country. The infantry, General A. Baird’s division, reached Salem, four miles from Murfreesboro, in good order, without molestation.

THE CAVALRY ADVANCE GUARD,

consisting of the Second Michigan and Ninth Pennsylvania regiments, came upon the rebel pickets just outside the little hamlet called Middleton, eleven miles from Triune. The rebels showed a force about equal to ours, and evinced a desire to obstruct our further advance. They were driven slowly along the execrable road, through the village, till they reached a dense woods beyond it, when they made a desperate stand, opening on our advance with two pieces of artillery. They held the woods and a ploughed field in front of it for an hour, shouting savagely and firing extremely wild.

THE FIGHT.

General Mitchell, impatient at the delay–for night was near at hand–ordered the Second and Ninth to dismount and charge across the field. The passage over the moist, ploughed ground, in the face of the enemy’s fire, was extremely difficult for dismounted men. But these two regiments had an excellent reputation to sustain, and they made the trip, reserving their fire till they approached within thirty yards of the rebel line, then delivering it with precision and rapidity. The graybacks could not stand it, and broke and fled most frantically, leaving eight dead men and sixty or seventy dead horses, but carrying off their wounded and the two guns. The enemy proved to be Brigadier General Martin’s command—part of Wheeler’s cavalry force. 0ur loss was two killed and six wounded. The cavalry camped near the field that night. Three log houses in the village—nearly half its complement of tenement–were accidentally burned during the melee by Tennessee cavalry of Mitchell’s command, who knew them to be the property of violent rebels.

ANOTHER SKIRMISH.

Next day, after another skirmish at Fosterville in which the rebels were again discomfited, the cavalry reached Christiana, on the Shelbyville pike, eight miles and a half from Murfreesboro, where they found Colonel Minty’s and Ed. McCook’s brigades of General Stanley’s cavalry, commanded by General Stanley in person. Infantry and artillery having come over from Triune via Salem in the meantime, quite an imposing force encamped at Christiana in the pouring rain on Wednesday night, and were ready for the offensive in any direction when the day came. Here, I learned that the Twentieth army corps (McCook’s) had passed down the pike in the direction of Shelbyville on Tuesday, and all day long General Granger waited for orders and listened to the sound of McCook’s cannon in the front, six miles away. The rain and the mud were fearful.

EXCITING RUMORS

were afloat that Sheridan’s division of McCook’s corps had met the rebels, and had been driven back in disastrous rout; that a vast force of enemies were approaching the reserve corps on the Shelbyville road; but Gen. Granger was unable to get hold of any positive information respecting either of the exciting topics. So isolated was the reserve that two days passed before we knew exactly where to find Rosecrans’ headquarters. During Thursday and Friday there was considerable skirmishing between pickets of the opposing parties, and our infantry were several times drawn up in line of battle, to await and repel an attack.

SATURDAY MORNING.

Twenty regiments of Stanley’s cavalry moved toward Shelbyville from Christiana, Generals Granger, Stanley and Mitchell at the head of a column of fours which stretched along the pike a distance of four miles. It was a splendid show of strength, and calculated to terrify any force we expected to meet. Four miles in front of Christiana, the cavalry came upon the pickets of the rebel force stationed al Guy’s Gap, and skirmishing began. The rebels were driven luck till we discovered their line of battle formed across the pike at the entrance of the gap.

GUY’S GAP

is naturally a very strong position, and we expected to find it fortified extensively and to meet with a stubborn resistance. The cavalry was deployed to the right and left, and the bugles of the twenty regiments sounded the advance. Ten minutes were sufficient to give us possession of the gap, from which we could see the rebels fleeing along the straight pike toward Shelbyville in the utmost confusion. While the force directly in front were engaged seizing the gap, the regiments on the right were engaged with a strong column of rebels which had been unearthed in that quarter. This column, we afterward learned, was the command of Colonel Cruse, Forrest’s right bower, who was marching from the vicinity or Eaglesville and Triune, across the country, to join General Wharton’s cavalry, near Hoover’s Gap. The presence of Colonel Cruse on our right was unknown to the rebels who held the Gap in front, and his meeting with our cavalry so near Shelbyville was unexpected. He retired with the loss of three men, made a detour toward Shelbyville, and attempted to cross the pike again. Here he met the advance of the Union column, in full pursuit of the rebels from the gap, and his passage was again blocked. This time he gave it up for a bad job and retreated towards Middleton, whence he had come. Since we have heard from Cruse in the vicinity of Triune, and presume he is endeavoring to reach Wharton by way of Columbia.

FORREST DANGEROUSLY WOUNDED.

From a prisoner I learn that Forrest is unable to fight just now, being in a dangerous condition from a wound received in the Spring Hill live fracas. I am convinced that up to the time we appeared in front of Guy’s Gap the rebels knew nothing of our advance in form. I am convinced, also, that had been blessed with sunshine instead of pouring rain all the while, General Rosecrans’ plans for the destruction of Bragg’s army would have succeeded before now.

PURSUIT OF THE REBELS—THEIR WORKS.

The rebel troops who made the stand at Guy’s Gap (Martin’s brigade, of Wheeler’s command) were hotly pursued five miles further down the pike, to the outer line of fortifications around Shelbyville, four miles from the town. Those outer works consisted of a line of rifle pits with flanking batteries, extending from Duck river on the left to Hog mountain on the right–a distance of eight miles. They had been built regardless of expense, and their completeness, location and finish showed them to be the work of a skillful engineer. Reaching this line of works, the rebels paused in their mad flight und made hasty preparation for another stand. A twelve-pounder

cannon, belonging to Wiggins’ rebel battery, was placed in position to rake the pike. The Seventh Alabama Cavalry supported the piece, and opened fire on the head of the Union column as it appeared before the works.

THE CHARGE

was sounded, the Union cavalry rode further up the pike, clamored over the earthworks, sabered such misguided beings as showed a belligerent disposition, and the line of rifle pits was ours. The rebels succeeded in getting away with their guns, but 459 privates, with all the officers of the Seventh Alabama cavalry, were temporarily lost lo the rebel service, prisoners of war. Three brigades of Infantry and two regiments of cavalry, a portion of General Leonidas Polk’s command, had evacuated the position five hours before, and retreated through Shelbyville toward Tullahoma.

THE CHASE WAS KEPT UP.

The Fourth United States cavalry and Seventh Pennsylvania in the advance were close upon the heels of the rebels as they entered Shelbyville. The chase for the last four miles was of the most exciting character. Houses along the road were filled with Union people, who came to the roadside fences, shouted, clapped their hands, hooted at the pale and panting rebels, and cheered the pursuers on. Here and there a jaded rebel horse would drop, with the blood gushing from its mouth and pouring from its wounded sides; the next instant ferocious blue jackets would be upon its terrified rebel rider, with keen sabre in hand, demanding unconditional surrender or swift death. Rebel canteens, haversacks, broken muskets, clothing and corn meal were strewn along the pike throughout the whole distance, from the earthworks to

the town, and dead bodies were numerous.

SHELBYVILLE—THE FIGHT.

It was half past six o’clock when the Unionists reached the town. Four pieces of Wiggins’ rebel battery were planted in the public square, facing towards Murfreesboro, and rebel cavalrymen were flying to and fro in wild confusion. General Wheeler himself was in command. The force, we afterwards learned, was five regiments of cavalry with the four pieces of cannon above mentioned. The cannon in the square opened on our brave fellows, and Wheeler rode about like a madman, trying to get his rebels in shape to make a fight. General Granger sent Lieutenant Colonel Minty with a flanking force of four regiments to our left, and ordered the Fourth United States cavalry and Seventh Pennsylvania to charge into the square and take those guns at all hazards. The charge was made in the presence of an admiring audience of Shelbyville people, who lined the sidewalks, filled the windows and covered the housetops and porches, regardless of bullets, which were flying through the streets from both directions. It was so fierce and desperate that Wiggins was able to fire but one shot from his cannon before he lost three of them. This single round ball cut down six men and four horses. The fourth piece was dragged out of the square, down past the railroad depot, across the Duck river bridge, and started on the gallop toward Tullahoma.

THE SCENE AT THE BRIDGE

beggars description. Men and horses crowded upon it inextricable confusion, the stream filled with rebels struggling to gain the opposite bank, our exasperated soldiers firing at them in the water; Wheeler frantically calling for volunteers to stay the Union torrent long enough for his escape. The First rebel cavalry answered his call, and made a really gallant stand, checking our advance momentarily, while Wheeler and his body guard dashed into the stream and swam for dear life and liberty. Upwards of fifty rebels were drowned in the passage of this stream, among them Major Reid, Wheeler’s adjutant general, and Major Buford, Forrest’s chief of

staff. Wheeler himself, thanks to the bravery of the First rebel cavalry, escaped. The regiment was destroyed or captured almost wholly to save a little major general. The flanking force of Colonel Minty by a citizen in regard to the location of the Tullahoma pike, and the number of fences they expected to encounter. They did not succeed in cutting off the retreat, and the remnant of the rebel force, who were so warlike in the morning, got off towards Tullahoma dispirited and dismayed.

IN POSSESSION OF SHELBYVILLE.

Thus, Saturday night at eight o’clock, General Granger was in possession of Shelbyville, with eight hundred prisoners, three pieces of cannon, twenty thousand bushels of corn and other stores, besides inflicting upon the rebels a loss nearly three hundred killed and wounded. Our total loss since leaving Christiana amounted to eighteen killed and three wounded. It was cheering to meet so many loyal people as we met in Shelbyville. The town has not been belied. Old people and young people, young men and maidens, waving little copies of the Stars and Stripes, stained and dusty from a year’s concealment in secret places, greeted us with “Thank God, you’ve come at last!” The Union feeling is so universally evinced that I did not wonder longer why the rebels “could not bear the town of New Boston.”

Colonel Brownlow’s First Tennessee cavalry participated in the attack. Many of his men were residents of Shelbyville in peaceful times. It was a sweet morsel to these men to fight rebels in the neighborhood of their former homes. A young Tennessean of BrownIow’s regiment rode up before his father’s door while the fight was going on. He dismounted hurriedly and embraced his aged parents, who hardly recognized him at first. The young warrior exchanged short greetings with them, the gray haired man holding his son’s carbine, the feeble mother grasping the bridle of her son’s horse, while the young man eagerly drank the water his pretty sister brought to him—a very pretty but fleeting picture of the “wanderer’s return.” The tableau was dissolved by the old man thrusting the gun into the soldier’s hand, bidding Charley “go on and get your revenge.” The restless Colonel was full of the spirit of his father. He jumped from his horse, kissed his sweetheart, whom his quick eye had singled out from a throng of excited maidens, mounted, again and joined in the charge. Another of Brownlow’s men—his wife looking on then shot the man who had driven him from Shelbyville in front of his own door. Incidents of this character were plenty.

The town of Shelbyville has been treated much better by the rebels since Buell left than one would expect. They left it last night, threatening to return today and burn it, but I fancy it is safe for the present.

The June 27, 1863 Battle of Shelbyville, addressed in detail here, is one of the most fascinating cavalry battles in the war. Minty’s single brigade, augmented by Col. William Brownlow’s First Middle Tennessee Cavalry, made a saber charge that broke and routed two full division of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps. Wheeler went flying into the Duck River, barely escaping capture. I know of no other similar cavalry charge during the entire course of the Civil War. But it has gotten little attention over the years. I aim to correct that.

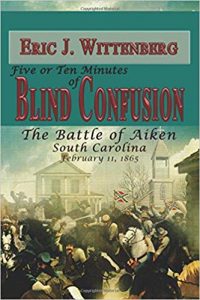

Scridb filter I am proud to announce the release of my newest title, Five or Ten Minutes of Blind Confusion: The Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, February 11, 1865. The short but ferocious cavalry battle at Aiken was the sole Confederate battlefield victory during Sherman’s 1865 Carolinas Campaign–it was one of the few Confederate battlefield victories in any theatre of the war in 1865–and had great strategic significance. Confederate commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler disobeyed orders to pursue Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry at Aiken, meaning that the defensive line of the Edisto River, south of Columbia, South Carolina, lacked sufficient manpower to hinder the advance of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s armies on Columbia. Thus, while Aiken was a tactical battlefield victory from Joe Wheeler, it was a strategic disaster that directly led to the fall and burning of Columbia.

I am proud to announce the release of my newest title, Five or Ten Minutes of Blind Confusion: The Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, February 11, 1865. The short but ferocious cavalry battle at Aiken was the sole Confederate battlefield victory during Sherman’s 1865 Carolinas Campaign–it was one of the few Confederate battlefield victories in any theatre of the war in 1865–and had great strategic significance. Confederate commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler disobeyed orders to pursue Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry at Aiken, meaning that the defensive line of the Edisto River, south of Columbia, South Carolina, lacked sufficient manpower to hinder the advance of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s armies on Columbia. Thus, while Aiken was a tactical battlefield victory from Joe Wheeler, it was a strategic disaster that directly led to the fall and burning of Columbia.

This book is the first and only detailed tactical study of this important but overlooked engagement. It features five excellent maps by master cartographer Mark Anderson Moore, and represents the second book that I have published with my friends at Fox Run Publishing. I will have copies to sign and ship in a week or so. In the interim, copies are available for sale here.

Scridb filter Those of you who know me in person, or who have been long-time readers of this blog, know how important my battlefield preservation work is to me. While telling the stories of the Civil War is of crucial importance to me, the preservation of hallowed ground is, without question, the most important work that I do when it comes to my historical work. Thus, it is my honor to share this article from the May 26, 2018 issue of The Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star:

Those of you who know me in person, or who have been long-time readers of this blog, know how important my battlefield preservation work is to me. While telling the stories of the Civil War is of crucial importance to me, the preservation of hallowed ground is, without question, the most important work that I do when it comes to my historical work. Thus, it is my honor to share this article from the May 26, 2018 issue of The Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star:

Central Virginia Battlefields Trust adds three to board of directors

May 26, 2018The Central Virginia Battlefields Trust has elected three new members to its board of directors. Chris Mackowski, John McManus and Eric Wittenberg will each serve three-year terms.

“John and Eric both bring excellent experience as attorneys, which is expertise a preservation organization like ours can always benefit from, and Chris and Eric are both top-notch historians,” said Tom Van Winkle, president of CVBT. “We have some projects in the works right now that are particularly relevant to their skillsets, so their additions to the board come at a fortuitous time for us.”

Chris Mackowski, Ph.D., is the editor-in-chief and co-founder of Emerging Civil War. He is a professor of journalism and mass communication at St. Bonaventure University, Allegany, N.Y., and historian-in-residence at Stevenson Ridge, a historic property on the Spotsylvania battlefield. He has also worked as a historian for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. Mackowski has authored or co-authored more than a dozen books on the Civil War, and his numerous articles have appeared in major Civil War magazines. He also serves on the national advisory board for the Civil War Chaplains Museum in Lynchburg.

Attorney John McManus has called Fredericksburg home for more than 22 years. As managing partner of Hirschler Fleischer’s Fredericksburg office and a member of the firm’s board of directors, McManus is active in the local business community and committed to preserving the area’s rich history. Among other leadership roles, McManus serves on the board of governors for the Community Foundation of the Rappahannock River Region and is a former board member of Rappahannock Goodwill Industries Inc.

Eric J. Wittenberg is an award-winning historian, blogger, speaker and tour guide. His specialty is Civil War cavalry operations, and much of his work has focused on the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps and on the Gettysburg Campaign. He is the author of 21 published books on the Civil War and more than three-dozen articles that have appeared in various national magazines. He is also deeply involved in battlefield preservation work and often assists the American Battlefield Trust, formerly the Civil War Trust, with its efforts.

The Central Virginia Battlefields Trust preserves land associated with four major Civil War campaigns: Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Incorporated in 1996, CVBT has since helped preserve more than 1,200 acres of historic battlefield terrain.

The Central Virginia Battlefields Trust is one of the leading local advocacy group partners for the American Battlefield Trust, and has done some remarkable battlefield preservation work in its own right, having saved 1200 acres of important battlefield land in and around the Fredericksburg, Virginia area.

It is my honor and my privilege to have been asked to join the CVBT board of trustees. I join a group of talented and dedicated volunteers who are committed to saving endangered battlefield land. By joining the CVBT board, I am able to make a more direct contribution to the preservation work that means so very much to me.

The CVBT covers its overhead from the dues that its members pay. Please consider joining the CVBT and help us to accomplish our goal of saving battlefield land. Every membership helps us to cover our overhead and to devote resources to buying battlefields. I hope that you will consider doing so. For more information about membership in the CVBT, please click here.

Scridb filter On Monday, I received a call from old friend Clint Schemmer, who is the communications manager for the Civil War Trust. Clint called with some very important news.

On Monday, I received a call from old friend Clint Schemmer, who is the communications manager for the Civil War Trust. Clint called with some very important news.

For the past few years, the Trust has expanded its scope of coverage to include the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. That work was being done by the Civil War Trust, and that just didn’t seem quite right. Clint called to tell me that the Trust has undergone a significant reorganization to accommodate these changes. He sent along the press release for it, which I reproduce for you below:

NATIONAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION GROUP FORMS AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD TRUST

New umbrella organization will build upon success of Civil War Trust in preserving our nation’s hallowed battlegrounds(Washington, D.C.) – The Civil War Trust, a national nonprofit preservation group recognized for its success in saving battlefield land, has formed the American Battlefield Trust — a new umbrella entity dedicated to preserving America’s hallowed battlegrounds and educating the public about what happened there and why it matters today.

The new umbrella organization reflects how the Civil War Trust’s battlefield preservation achievements have grown and its mission expanded to include other conflicts from America’s formative first century. In 2014, at the request of the National Park Service, the Trust extended its mandate to include protection of Revolutionary War and War of 1812 battlefields. Its decision to do so coincided with the passage of federal legislation aimed at preserving battlefields of those two conflicts. Since then, the Trust has saved nearly 700 acres of battlefield land associated with the American Revolution and War of 1812 while continuing to save Civil War battle sites at a record pace.

Earlier this month, the Department of Interior announced that the Trust had been selected to serve as the federal government’s nonprofit partner for the commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States. The organization’s commitment to protecting Civil War battlefields was recently underscored by the announcement that it would be saving 18 acres of core battlefield land on historic Seminary Ridge at Gettysburg.

“We see preserved battlefields as outdoor classrooms that both illuminate and inspire,” said American Battlefield Trust President James Lighthizer. “They allow young and old alike to walk in the footsteps of America’s first citizen soldiers. No Hollywood movie, documentary, or museum exhibit can compare to standing amid the now-quiet trenches of Yorktown or gazing across the field of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg.”

The Civil War Trust will continue as the principal division under the American Battlefield Trust umbrella, focusing on battlefields and educational outreach related to that conflict. A second division known as the Revolutionary War Trust will serve a similar function, concentrating on battlefields associated with America’s War for Independence. According to Lighthizer, “this new organizational structure gives us the strength and flexibility needed to protect critically important battlefield land in an increasingly competitive real estate market.”

The formation of the American Battlefield Trust is the latest step in the evolution of the modern battlefield preservation movement, which began in the mid-1980s in response to the loss of important historic sites to spreading commercial and residential development. The new entity is a direct descendant, through a series of mergers and name changes, of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites, founded by a group of professional historians and preservation advocates in 1987.

The organization is best known for its high-profile battlefield preservation efforts, including protection of the historic epicenter of the Antietam battlefield, the site of George Washington’s famous charge at Princeton, the Slaughter Pen Farm at Fredericksburg, and Robert E. Lee’s battlefield headquarters at Gettysburg. In addition, as the Civil War Trust, it engaged in grassroots campaigns to prevent development at Chancellorsville and the Wilderness in Virginia; Franklin, Tennessee; and Morris Island, South Carolina (site of the famous charge portrayed in the movie Glory).

“Over those years and under a variety of names, we have saved nearly 50,000 acres of battlefield land throughout the United States, while earning accolades for being one of the most efficient and effective nonprofits in the nation,” said Lighthizer. “Now, as the American Battlefield Trust, we will continue that tradition of preservation leadership.”

Although primarily known for its land preservation successes, the organization is also firmly committed to promoting the rich and diverse history of America’s first century conflicts. Using battlefield land as a unique and powerful teaching tool, the Trust’s educational efforts include popular videos, you-are-there Facebook Live broadcasts, GPS-enabled smartphone apps, online battle panoramas, animated maps, classroom field-trip sponsorships, a national Teacher Institute, hundreds of website articles and images, and “Generations” events that encourage family members of all ages to experience history in the places where it occurred.

The American Battlefield Trust is dedicated to preserving America’s hallowed battlegrounds and educating the public about what happened there and why it matters today. To date, the nonprofit, nonpartisan organization has protected nearly 50,000 acres of battlefield land associated with the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War. Learn more at www.battlefields.org.

The Trust has been–and remains–the most effective battlefield preservation advocacy group in the country, and I have long supported its work. Now it will be able to continue its work in preserving Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites under an appropriate name while still doing great work in preserving Civil War battlefields. Please continue to support the Trust’s efforts. Nobody does it better.

Scridb filterDr. John Wyeth, who documented the exploits of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry in the latter portion of the Civil War, started out as a private in the 4th Alabama Cavalry of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s corps. Wyeth was present at the June 27, 1863 Battle of Shelbyville, Tennessee, during the Tullahoma Campaign. Shelbyville was an overwhelming Union victory, where Col. Robert H. G. Minty’s single brigade, augmented by two additional regiments, shattered Wheeler’s command, routed it, and sent Wheeler himself flying headlong into the deep, rushing waters of the Duck River to escape capture.

Writing in 1898, Wyeth left this vivid description of the mounted fighting at Shelbyville. It’s too good of a description not to share:A cavalry fight well sustained on both sides is lively enough when one takes part in it, but it seems exceedingly tame on paper. This one did not lack in spirit. About a score of such “scraps,” some of which, of larger growth, have passed to place on the bloodiest pages of history, the writer does not recall a contest which, for downright pluck in giving and taking hard and heavy knocks through several hours, surpasses this Shelbyville “affair.” The carbines and rifles were flashing and banging away, at times in scattering shots, when the game was at a long range, and then when a charge came on, and the work grew hot, the spiteful, sharp explosions swelled into a crackling roar, like that of a canebrake on fire, when in a single minute hundreds of the boilerlike joints have burst asunder. Add to all of this the whizzing, angry whir of countless leaden missiles which split the air about you; the hoarse unnatural shouts of command–for in battle all sounds of the human voice seem out of pitch and tone; the wild, defiant yells and the answering huzzahs of the opposing lines; the plunging and rearing of the frightened horses; the the charges here and there of companies or squadrons, or more than these which seem to be shot from the main body, as flames shoot out of a house on fire; here and there the sharp, quick cry from some unfortunate trooper who did not hear one leaden messenger–for only those are heard which have passed by; the heavy, soggy striking of the helpless body against the ground; the scurrying runaway of the frightened horse, as often into danger as out of it, whose empty saddle tells the foe that there is one less rifle to fear–all these sights and sounds go to make up the confusing medley of a battlefield. And then there was the artillery, not thundering away–for artillery never thunders when one is near it. Two or three miles away the reverberations of the atmosphere convey to the ear the sound of distant thunder, but when, on the field, one faces or stands behind the battery which is engaged, the noise seems more like the sudden throb or impulse of some huge pump than the prolonged muffled sounds which are akin to thunder. So, for nearly three hours, passed this little fight.

That vivid description could have been of any cavalry battle, not just Shelbyville–it would be just as applicable to the Battle of Brandy Station, as just one example. It’s one of the finest descriptions of mounted combat I’ve yet found.

Scridb filterHere’s the next in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten cavalrymen of the American Civil War.

George S. Acker was born near Rochester, New York on December 25, 1835. In 1839, his family relocated to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where he lived the rest of his life. “He was a bright and chivalrous young man,” recalled a local resident. He worked in a Kalamazoo hotel before the outbreak of the Civil War, where he was a “popular assistant.”

With the coming of war, he decided to enlist. He helped to recruit a company of the 1st Michigan Cavalry and was commissioned a captain. While serving in the 1st Michigan Cavalry, Acker “took an active part in the contests at Winchester, Orange Court Honse, Cedar Mountain, and the second Bull Run, where, a charge that he led freed Lt. Col. Charles H. Town, who had been captured, and brought him back into the Union lines, badly wounded. He was made Major on September 2, 1862 in recognition of his gallantry.

When the 9th Michigan Cavalry was formed that fall, he was assigned as its lieutenant colonel.The 9th Michigan Cavalry was mustered into service in May 1863. The 9th Michigan, then commanded by Col. James L. David, was ordered to Covington, Kentucky, leaving by detachments, on May 18, 20, and 25, 1863, respectively. Then, on June 4, the regiment marched to Hickman’s Bridge, where on June 12, they were ordered to Mount Sterling, to pursue guerrillas, whom they overtook at Triplett’s Bridge, then completely routed.The regiment then joined the pursuit of Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry, which invaded Indiana and Ohio. Acker “was very prominent in the pursuit and capture of the notorious rebel Gen. John H. Morgan in Ohio in July and August 1863,” noted his obituary, which also said, “He said to his command, ‘Come,’ and led them wherever the enemy opposed or danger threatened.” The 9th Michigan played a significant role at the July 19, 1863 Battle of Buffington Island in southeastern Ohio. In November 1863, Acker was commissioned colonel of the 9th Michigan Cavalry.The Detroit Free Press described Acker’s role in the battle of Morristown, fought on December 10, 1863 as part of the Knoxville Campaign: “Col. Acker threw himself at the head of his regiment and shouted: “Boys, charge the rascals with a yell,’ and himnelf setting the example, with revolver in hand, charged full speed up the hill. The enemy broke ranks and ran in confusion to the rifle-pits, and when the boys saw Col. Acker standing in the rifle-pits sending its contents along the trender, it was enthusiasm run mad that sent his men like a swarm into tbe ditches. It was in vain the rebels tried to stay the storm. After the first charge was fired our boys clubbed their muskets, and thus fought their way through their fortifications.” Acker was wounded in the right leg in combat at Bean’s Station on December 14, 1863 during the Knoxville Campaign. Acker returned to duty in March 1864, in time for the beginning the Atlanta Campaign and commanded his regiment throughout that critical 1864 campaign.

He briefly commanded a brigade during the March to the Sea, and retained command of his regiment for the rest of the war, participating in the battles of the Carolinas Campaign and then in the pursuit of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army to Raleigh, North Carolina. A soldier of the 92nd Illinois remembered him as “a cool and brave cavalry soldier.” He was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers at the end of the war, and mustered out in June 1865. His obituary noted that “His services are often referred to as among the most valuable and gallant of the many excellent officers of Michigan regiments.”

After the Civil War, he led a quiet life, working as a hotelkeeper and milkman. Acker died on September 6, 1879 at the young age of 44. He apparently never married, as his obituary indicates that he was survived by his mother and sister. He was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Union City, Michigan.

Here’s to Bvt. Brig. Gen. George S. Acker, forgotten cavalryman, who did his duty well and honorably throughout the Civil War.

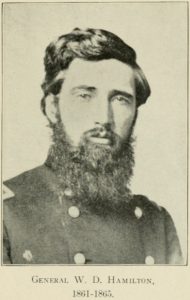

Scridb filterWilliam Douglas Hamilton was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland on May 24, 1832. He immigrated to the United States with his parents and two siblings six years later, and the family settled on a 200-acre farm near Newark in Licking County, Ohio. Two uncles had had settled in Ohio three years earlier, and parents followed their brothers to America, settling in a a Scottish enclave that developed along the National Road in Central Ohio.

As a youth, he worked on the farm and then taught school to earn his way through college and then law school. He graduated from Ohio Wesleyan College in Delaware, Ohio and from the Cincinnati Law School in 1859. He then established a law office in Zanesville and practiced law until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. When Fort Sumter was shelled in April 1861, Hamilton was recuperating from typhoid fever. He immediately decided to enlist.

Abandoning his law practice, he raised the first company for three years’ service in that part of Ohio, and was assigned to the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry as captain of Company G. He served in the West Virginia and Shenandoah Valley campaigns of 1861 and 1862. Fortunately, he was at home in Zanesville on recruiting duty when his regiment surrendered to Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s troops at Harpers Ferry in September 1862, so he avoided that disgrace.

In December 1862, Ohio Governor David Tod directed Hamilton to recruit the 9th Ohio Cavalry. The regiment was organized in 1863 for three years’ service. The first four companies mustered in at Zanesville in January 1863, and it took until September, October, and December for the remaining eight companies to be mustered into service. The first four companies were organized as a battalion and placed under Hamilton’s command. The regiment was finally completed and united in Alabama in early 1864. Hamilton was originally commissioned as a major of the new regiment, earning promotions to lieutenant colonel in 1863, and finally to colonel later that year. He was known as an officer who “takes great care of his soldiers” and who “does not let them suffer.” Two brothers, Robert and Henry, also enlisted in the same company and were killed during the war.

The 9th Ohio Cavalry served honorably in the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and the Carolinas Campaign. In particular, Hamilton and the 9th Ohio served critical roles in the December 4, 1864 Battle of Waynesboro, Georgia during the March to the Sea, and at the February 11, 1865 Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, where a cousin, Lt. Arthur Hamilton, the regimental adjutant of the 9th Ohio Cavalry, was mortally wounded.In all, William D. Hamilton served one year in the infantry and then three years in the cavalry during the course of the American Civil War. Among the battles he participate din were Cheat Mountain, Decatur, Buckhead Creek, Waynesboro, Aiken, Averasboro, and Bentonville. He was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers for “gallant and meritorious service rendered during the campaign ending in the surrender of the insurgent armies of Johnson and Lee” upon recommendation by Sherman and Judson Kilpatrick.

After the Civil War, Hamilton abandoned the practice of law and became an industrialist in the coal and iron business. He successively was president of a rolling mill company located in Newark, Ohio. He organized and served as treasurer of the Newark, Somerset and Shawnee Railroad, which was later purchased by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. He then served as president of the Ogden Iron Company at Orbiston, Hocking County, Ohio, which later merged with another company. Then, he acted as president of the Hamilton Coal and Iron Company, operating in Athens County, Ohio. Finally, his last role was as president of the Southern Slate Company.Hamilton was a Republican, a member of the Wells Post, G.A.R., in Columbus, Ohio, the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, and the First Congregational Church in Columbus. He published a well-regarded memoir of his wartime service in 1915 titled Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman After Fifty Years.

Hamilton married Sarah Cheaver Abbott of Zanesville in 1866. The couple had two daughters, Mrs. C. E. Gillette, wife of Major Gillette of Philadelphia, and Mrs. Charles E. Sudler, of Chilhowee, Tennessee and two sons, William E. Hamilton of Columbus and Charles R. Hamilton of Cleveland. His grandson, Douglas Hamilton Gillette, was a member of the West Point Class of 1915, and Hamilton dedicated his memoir to his grandson.

Hamilton died in Columbus, Ohio on January 22, 1916, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Greenlawn Cemetery. Sarah Hamilton died in 1920 and was buried alongside her husband. She also rests in an unmarked grave.

The Central Ohio Civil War Roundtable has made the marking of General and Mrs. Hamilton’s graves a group project. We hope that it will come to fruition during 2018, as this forgotten horse soldier deserves recognition for his honorable service during the Civil War.

Here’s to William Douglas Hamilton, forgotten Ohio cavalryman.

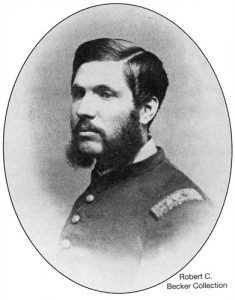

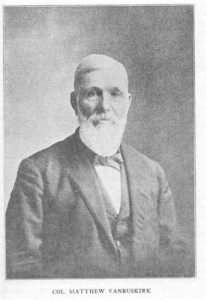

Scridb filterIt’s been a very long time since my last post, and even longer since my last Forgotten Cavalrymen profile. I’ve been working on the February 11, 1865 Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, which will spur several of these profiles. Here’s the first one, of Lt. Col. Matthew Van Buskirk of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry.

Matthew Van Buskirk was born in Buckmantown, Clinton County, New York, on January 1, 1835. He was the son of Lorenzo Dow Van Buskirk and Louisa Van Buskirk, and had one brother, Albert, born March 20, 1841 (Albert Van Buskirk was killed in action at the Battle of Drury’s Bluff near Petersburg, Virginia on May 16, 1864). After completing his education, the young man relocated to Illinois in 1851, and was still living there with the coming of war in 1861.

He enlisted in the 92nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which was organized at Rockford, Illinois, on September 4, 1862, and was quickly elected captain of Company E. The 92nd Illinois consisted of five companies from Ogle County, three from Stephenson County, and two from Carroll County.The newly formed regiment left Rockford, 11 October 1862, with orders to report to Gen. Horatio G. Wright, in command of the defenses of Cincinnati, Ohio. The regiment was assigned to Gen. Absalom Baird’s Division of the Army of Kentucky. These men soon marched into the interior of Kentucky and was stationed at Mt. Sterling in October to guard against rebel cavalry raids during Braxton Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky. Later, it was assigned to Danville, Kentucky. On January 26, 1863, Baird’s division, including the 92nd Illinois, was transferred to the Army of the Cumberland. The division was assigned to serve in Franklin, Tennessee, and assisted in the pursuit of Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn’s Confederate cavalry raiders. They advanced to Murfreesboro,and occupied Shelbyville, Tennessee on June 27, 1863.

The 92nd Illinois Infantry converted to mounted infantry on July 22, 1863 and was rearmed with Spencer repeating rifles. It was then assigned to join Brigadier General John T. Wilder’s Lightning Brigade for the rest of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’ command of the Army of the Cumberland. During the early phases of what became the Chickamauga Campaign, with the Lightning Brigade leading Rosecrans’ advance, the 92nd Illinois crossed the mountains at Dechard, Tennessee, and took part in the movements opposite and above Chattanooga. The 92nd Illinois then crossed back over the mountains and joined Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas at Trenton, Alabama. On the morning of September 9, the Lightning Brigade led the Union advance to Chattanooga, helping to drive the Confederates from Point Lookout. The 92nd Illinois then entered Chattanooga, unfolding the Union banner on the Crutchfield House. They then pursued the retreating Confederates. Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry attacked the Lightning Brigade near Ringgold, Georgia, inflicting significant casualties on the Federals. At Chickamauga, the 92nd Illinois supported Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds’ Division of Thomas’ 14th Corps.

In April, 1864, the 92nd was doing picket duty at Ringgold, Georgia. On May 7, 1864, the 92nd Illinois, which had now been converted to light cavalry and armed with cavalry weapons, began Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign as part of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s Third Cavalry Division. The 92nd Illinois participated in the Battle of Resaca, Kilpatrick’s failed raid around Atlanta, as well as the Battles of Bethesda, Fleet River Bridge, and Jonesboro, where the regiment lost one-fifth of the men engaged. The regiment moved from Mount Gilead Church, west of Atlanta, on October 1, and took an active part in the operations against Hood’s army, including taking heavy losses at Powder Springs. About this time, Van Buskirk was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 92nd Illinois after Col. Smith D. Atkins was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers and assumed command of a Federal cavalry brigade.

The 92nd Illinois then participated in the various engagements and skirmishes in Sherman’s March to the Sea and then through the Carolinas Campaign of 1865. During its term of service, the 92nd Illinois participated in some forty battles and skirmishes. The regiment was mustered out at Concord, North Carolina, on June 21, 1865, and was then discharged at Chicago, Illinois, on July 10, 1865.

Van Buskirk “was popular with his soldiers and trusted by his superior officers,” noted one biographer. With the end of the war, he settled in Iowa Falls, Iowa, where he successfully operated a store selling boots, shoes and crockery and later dry goods and other items, growing his business into a general merchandising business. Later, he became a gentleman farmer. He married Nellie C. McGiven in 1866, and they had seven children together. Van Buskirk died on January 10, 1901 and was buried in Iowa City’s Union Cemetery. “He was a clear-brained, noble-minded man of action and his life record is worthy of emulation by the youth of this locality whose careers are yet matters for the future to determine,” declared his biographer.Here’s to forgotten cavalryman Matthew Van Buskirk, who performed his duty capably and with honor throughout the American Civil War.

Scridb filterMy old friend and fellow cavalry historian Bob O’Neill has started a new blog that I want to recommend to you. Bob is THE authority of the cavalry battles in the Loudoun Valley of Virginia during the Gettysburg, and that’s one of the focuses of the blog, which is called Small but Important Riots. That’s the title of Bob’s excellent but LONG out of print on these engagements from 1993. Bob’s working a new edition–truly excellent news for those of us interested in these fascinating engagements–and has also written a very good book on the cavalry division assigned to the defenses of Washington until just before the Battle of Gettysburg that I commend to you.

Bob’s new blog, which I have added to the blogroll, focuses on cavalry actions in the Loudoun Valley, and contains some really interesting bits. If you have an interest in Civil War cavalry, please check it out.

Scridb filter

An 1876 portrait of Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. Many of Meade’s possessions are in this collection

Civil War Museum transfers collection to Gettysburg with Constitution Center exhibit planned

Updated: May 4, 2016 — 3:22 AM EDT

by Stephan Salisbury, Culture WriterThe homeless Civil War Museum of Philadelphia, steward of what scholars regard as one of the finest collections of Civil War materials anywhere but possessing no place to display them, reached an agreement Monday to transfer ownership of its roughly 3,000 artifacts to the Gettysburg Foundation, the private, nonprofit partner of the National Park Service.

At the same time, the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall has agreed to mount a permanent exhibition exploring the constitutional impact of the Civil War, using artifacts drawn from what is now the foundation’s Gettysburg collection.

It is believed it will be the first museum exhibit exploring the war’s constitutional legacy.

Like the Flying Dutchman, the Civil War Museum has traveled for years, rich in its memories of the dead, but invisible and portless in the land of the living.

“Our goal is to preserve the collection with integrity and to ensure the collection will be available to the citizens of Philadelphia,” said Oliver St. Clair Franklin, board chairman of the Civil War Museum. “And we’re very pleased the National Constitution Center is going to preserve space for an exhibition to explore what was our greatest constitutional crisis.”

Joanne M. Hanley, president of the Gettysburg Foundation, which owns and operates the visitor center and 22,000-square-foot museum at Gettysburg National Military Park, called the collection “priceless.”

“The significance of these pieces, you can’t put into words,” she said. “There’s no hyperbole that can describe them.”

Jeffrey Rosen, chief executive and president of the Constitution Center, said the future constitutional exhibition, focusing on passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, would be a few years in the making.

For one thing, he said, all money for the exhibition, which he estimated might cost up to $2 million, would have to be in hand before proceeding.

“Our exhibition is contingent on securing funding in advance,” he said. “As soon as the funds are secured, we’ll have a better sense of the timeline.”

The postwar constitutional amendments, among other things, abolished slavery, addressed equal protection under the law, defined citizenship, and guaranteed the right to vote.

Sharon Smith, president and chief executive of the Civil War Museum, said the collection was currently in storage at Gettysburg, where it played a central role in the Gettysburg Foundation’s commemorative exhibition related to the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Gettysburg.

That exhibition closed last year, but Hanley said the collection would be deeply mined for a long-term exhibition scheduled to open at the end of June on the art of the Civil War.

“We will always have major pieces on view,” Hanley said.

Smith said she believed the agreement with the foundation and the NCC would conclude the Civil War Museum’s odyssey, which began in earnest about a decade ago and has included lawsuits, virtual closure, failed partnership efforts, an aborted relocation to Richmond, Va., a failed state bailout, a failed deal with Independence National Historical Park, and seemingly endless searches for a home.

“It’s been like a soap opera,” Smith said. “It’s been going on for years and years.”

The roots of the museum go back to the end of the Civil War, when Union officers formed the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS). In 1888 they founded a museum in Philadelphia, and over the years, Union officers and their descendants donated a rich array of artifacts, including plaster casts of Lincoln’s hands and face, battle photos, Jefferson Davis’ smoking jacket, battle flags, the first John Wilkes Booth wanted poster, bullet-riddled tree trunks, photos of black soldiers and regiments, diaries, letters, drawings, swords, and firearms – a seemingly endless stream of personal, quirky, evocative objects.

For years, the collection was housed in a stately Pine Street mansion. But internal squabbles broke out in 2000, sparked by dwindling finances, declining visitation, a failed affiliation with the Union League, and an incendiary proposal to move everything to a new museum in Richmond, former capital of the Confederacy.

The Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office stepped in and blocked the Richmond move. In the next several years, the Pine Street building was sold. An effort to move into the historic First Bank of the United States, located in Independence Park, fell through. The artifacts found homes in boxes, and the museum searched in vain for a home in Philadelphia, city of its birth.

On the plus side, however, a strong affiliation grew with the Gettysburg Foundation, which has conserved and stored much of the museum’s collection and now stores it, officials said.

(The famous preserved head of Gen. George G. Meade’s horse, Old Baldy, which was displayed by the Civil War Museum for many years, was returned to its owner, the Grand Army of the Republic Museum and Library in Frankford, in 2010.)

The framework of the agreement just announced – the transfer of ownership of artifacts to Gettysburg, with a subsequent long-term loan to the NCC – emerged in the last two years as the best alternative to a stand-alone Philadelphia museum housing the collection.

In an April 25 letter to museum chair Franklin, the head of MOLLUS in Pennsylvania said his organization was “saddened” to learn that despite “a decade of work,” the museum would not have a new museum home in Philadelphia.

That said, commander-in-chief James Alan Simmons wrote that the museum’s plan of transferring the artifacts to the Gettysburg Foundation is “prudent and appropriate” and “the best alternative.”

The Civil War Museum, while giving its artifacts to Gettysburg, remains owner of an archive of more than 10,000 documents – journals, diaries, papers, photographs, books. Those materials are housed at the Union League, under a separate stewardship agreement, and are available for research.

“We’re running on fumes,” Smith said, regarding the museum’s finances. “There’s virtually no money. We’re down to a very small amount. That’s why it’s important to make sure all this is taken care of.”

ssalisbury@phillynews.com

215-854-5594

@SPSalisbury

Count me as being vehemently opposed to this arrangement. Having seen that collection, I know it is nothing short of spectacular. The airport terminal that is the Gettysburg Visitor Center already fails to display the vast majority of the artifacts in the Rosensteel Collection, claiming lack of display space. If that’s the case, what are the odds of even a small percentage of these items ever being displayed again? Slim to none.

Shame on former Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell for breaching the agreement to fund a new museum.

These items should be on display at the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, where at least they would be seen, instead of languishing in storage.

The Constitution Center exhibit will be great. I attended an event with Jeffrey Rosen at Dickinson College in March, and know him to be a dedicated and enthusiastic director of a great project. But that exhibit is NOT a Civil War exhibit. It’s constitutional law exhibit, and there is no place in it for most of the artifacts in the MOLLUS Museum’s collection.

I will, however, be pleased to see some of those artifacts back home in Philadelphia where they belong, which will be the best thing about that exhibit.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like