Month:

October, 2011

Today, I received the sad news that my old friend Blake Magner has died. Blake did the maps for nearly half of my books, and we had a great working relationship. Blake was a Vietnam War veteran, and he was a fellow who enjoyed an adult beverage or six or seven. He could be crusty, but he was always fun to be around, and always good for a laugh.

Today, I received the sad news that my old friend Blake Magner has died. Blake did the maps for nearly half of my books, and we had a great working relationship. Blake was a Vietnam War veteran, and he was a fellow who enjoyed an adult beverage or six or seven. He could be crusty, but he was always fun to be around, and always good for a laugh.

For years, he was the book review editor for Civil War News, and I worked with him in that capacity. I also represented him and his company, CW Historicals, professionally, so I had a lot of dealings with Blake over the years.

You will be missed, old friend. Rest well. And have a beer with Brian Pohanka for me, please.

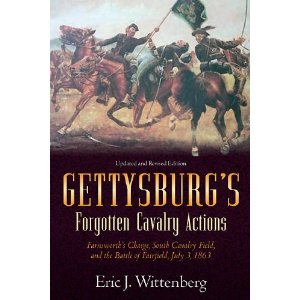

Scridb filter For those of you who have been waiting for the new edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions yesterday. The History Book Club and the Military Book Club have made a deal with Savas-Beatie to issue a special hardcover edition of the book for their members. That process has slowed up the printing process for the softcover edition, but I’m excited about it. This book has never had a hardcover version, nor did I ever expect that it would, so I am very excited about that.

For those of you who have been waiting for the new edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions yesterday. The History Book Club and the Military Book Club have made a deal with Savas-Beatie to issue a special hardcover edition of the book for their members. That process has slowed up the printing process for the softcover edition, but I’m excited about it. This book has never had a hardcover version, nor did I ever expect that it would, so I am very excited about that.

The downside is that it will only be available to book club members. I will get a couple of personal copies, but I do NOT expect to have any to sell. If you want the hardcover edition, you will have to join the book club and purchase it that way. But I figured that you should know that that option will be available.

Scridb filterFor those of you who have been waiting for the release of my book on the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, here’s an update for you. I finished my review of the draft of the index for the book yesterday and signed off on it. That means that I have now completely signed off on the page proofs. As soon as my final changes get made, it’s ready for final proofread and then it’s off to the printer.

I will keep you posted as to release date once I know it.

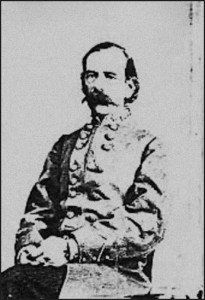

Scridb filterIt’s been quite a while since I last profiled a forgotten cavalryman. In many instances, the soldiers that I profile were heroic in their own but were nevertheless forgotten by history. In this instance, we celebrate a soldier whose incompetence and inefficiency make him worthy of remembrance. I learned of the inefficient career of William L. “Mudwall” Jackson while working on my White Sulphur Springs book, and realized that he’s one of those forgotten horse soldiers who deserves to be remembered, if for no other reason than his magnificent nickname.

Jackson, a second cousin of the lamented Confederate hero, Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, was born on February 3, 1825 in Clarksburg in what later became West Virginia. He was a descendant of John Jackson, a member of a landed Irish family who settled in Maryland about 1748, and twenty years later removed to the Buckhannon River region of western Virginia. His son Edward was the grandfather of both William L. Jackson and Thomas J. Jackson. One of John Jackson’s sons served as a Congressman from Virginia, and one of his grandsons later served as governor of West Virginia.

Young William’s father died in 1836, when William was only 11, leaving the family with serious financial problems. The boy ended up with the responsibility of the bulk of the chores on the family farm. In 1838, his mother remarried. His new stepfather, although a minister, harbored political aspirations, which evidently rubbed off on William. An uncle, John Jay Jackson, took in William and allowed the young man to apprentice in his law office in Parkersburg in what became West Virginia. John Jackson was a prominent and prosperous local attorney, and William learned the tricks of the trade from his uncle.

In 1847, he completed his legal studies and was licensed to practice law, which became a lifelong pursuit. He returned to his home town of Harrisville, where he opened his own law office. Jackson’s career as a jurist and Democratic public official during the ante-war period was prominent and distinguished. He served as Commonwealth’s Attorney in his district and was twice elected to the Virginia Legislature. He also served twice as Second Auditor, as Superintendent of the State Library Fund and as Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1857-1860). In 1860, he was elected Circuit Judge of the Nineteenth Judicial district of Virginia. He married Sarah Elizabeth Creel on December 19, 1849, and together they had three children.

William L. Jackson was a big man, standing about six feet tall and weighed about 200 pounds. He had a shock of dark red hair and piercing blue eyes like those of his famous cousin, all of which made him stand out in a crowd. Jackson was not known as an eloquent speaker, but he was known as a forceful one.

In 1861, when he had been but once around his circuit, the war broke out. Judge Jackson strongly supported Virginia’s secession and enlisted in the Confederate army as a private. He quickly made his way up the ranks. In May, 1861, Major F. M. Boykin, Jr., writing from Grafton, recommended that General Robert E. Lee appoint Judge Jackson to military command at Parkersburg, as “a gentleman of great personal popularity, not only with his own party, but with those opposed to him politically, and devoted to the interests of Virginia, to the last extremity.”

On May 30, the advance of a strong Union column drove a small Confederate force out of Grafton. At daybreak on June 3, the Federals surprised this same unit, commanded by the Confederate Colonel George A. Porterfield, at Philippi, forcing Porterfield to withdraw his green and bewildered troops south to Beverly and then twelve miles further to Huttonsville. The Federal seizure of Beverly, at the junction of the Staunton-Parkersburg stage road and the turnpike to Grafton, would secure northwestern Virginia for the Union and place Staunton in grave danger. All Confederate troops available were hurried there from Staunton, and a qualified officer, Colonel Robert Selden Garnett, Adjutant General of Lee’s headquarters, was ordered to proceed to Western Virginia to assume command of these troops.

Jackson was commissioned a lieutenant colonel of Virginia volunteers, and reported for duty to Colonel George A. Porterfield at Huttsonville, Randolph county, in June. Two new regiments of infantry were organized, and Jackson was commissioned colonel of one of them, the 31st Virginia Infantry. Jackson established his headquarters at Hunttonsville, where he was responsible for defending the so-called “Huttonsville Line”, which stretched for about thirty miles from southwestern Pocahontas County to Warm Springs in Highland County. His primary responsibility was to block any movement toward Staunton by Union forces.

In 1862 he became a volunteer aide on the staff of his cousin, Stonewall Jackson. While serving on his famous cousin’s staff, Jackson served in the campaigns and battles around Richmond, Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Harpers Ferry and then at Antietam.

On February 17, 1863, the Confederate War Department authorized Jackson to raise a regiment for the Provisional Army of the Confederate States of America within the lines of the enemy in West Virginia. By early April, he had organized and recruited a new unit, the 19th Virginia Cavalry, and Jackson was elected colonel. The new regiment joined the brigade of Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins, as part of the Army of West Virginia, commanded by Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones.

The newly-formed 19th Virginia Cavalry participated in several raids, with Jackson commanding his regiment and acting as Jenkins’s adjutant general. His men joined the Jones-Imboden Raid against the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, where the unit secured 300-400 new recruits. In July, he commanded a second expedition to Beverly, where and at Huttonsville he was engaged with Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell’s Fourth Separate Brigade of the Middle Military District command. He continued in the department of Western Virginia, frequently opposing Federal incursions, his command increasing to the dimensions of a small brigade of cavalry, during the remainder of 1863. His lackluster pursuit of Averell’s raiders during the August 1863 raid that culminated in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs earned Jackson the unflattering moniker of Mudwall.

The newly-formed 19th Virginia Cavalry participated in several raids, with Jackson commanding his regiment and acting as Jenkins’s adjutant general. His men joined the Jones-Imboden Raid against the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, where the unit secured 300-400 new recruits. In July, he commanded a second expedition to Beverly, where and at Huttonsville he was engaged with Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell’s Fourth Separate Brigade of the Middle Military District command. He continued in the department of Western Virginia, frequently opposing Federal incursions, his command increasing to the dimensions of a small brigade of cavalry, during the remainder of 1863. His lackluster pursuit of Averell’s raiders during the August 1863 raid that culminated in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs earned Jackson the unflattering moniker of Mudwall.

While pursuing Averell through Huntersville, Jackson’s troopers found “Mudwall Jackson” scrawled on the walls of the old county courthouse, “the principal feature of which was a complaint that ‘Mudwall Jackson’ would not fight,” as Confederate soldier John McNeel reported. McNeel saw this graffiti a few days after Averell’s men evacuated Huntersville, “and it was understood by the Confederate soldiers as having been put there by a Yankee soldier, and as we Confederates understood it at the time, the animus of the verse was because the dead ‘Stonewall’ had been so hard on the Yankees, and the live ‘Mudwall’ had escaped their net.”

“The fact is, he was as brave a man as lived, and never refused to fight, when the attendant circumstances were anything like equal,” claimed one of Jackson’s men. While Stonewall Jackson was most famous for his brigade’s stand at the First Battle of Bull Run, Mudwall Jackson was notorious for giving way. A Confederate soldier explained the origin of the nickname: “We called him ‘Mudwall’ in contradistinction from Stonewall Jackson because ‘Old Averill’, as we called Gen. Averill, always without an exception ran over him, knocked him down and ran him off.”

Averell nearly destroyed Jackson’s small brigade during the November 1863 Battle of Droop Mountain. After defeating Jackson’s command at Mill Point in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, Averell drove the Southern cavalry to Droop Mountain, where Brig. Gen. John Echols’s infantry brigade reinforced Jackson’s cavalry. In the Battle of Droop Mountain, Averell turned the Confederate flank and routed the Southern command from the field, inflicting another ignominious defeat upon Jackson’s little brigade.

In the spring of 1864, Jackson was stationed at Warm Springs. He fought at Cloyd’s Mountain in early May, where Jenkins was killed, and then he joined Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s command. He assumed command of a cavalry brigade, participating in opposing Maj. Gen. George Crook’s May 1864 expedition, and he helped to defend Lynchburg from the advance of Maj. Gen. David Hunter’s army in June. After the repulse of Hunter’s army, Breckinridge’s command–and Jackson’s brigade, joined Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s army as it advanced down the Shenandoah Valley, crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, and advanced on the defenses of Washington, D. C. When Early fell back, Jackson commanded his brigade when it served as Early’s rear guard, and repulsed a Federal attack at Rockville, Md.

His brigade was assigned to the cavalry division of Maj. Gen. Lunsford Lomax, and was involved in nearly every engagement during the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, including the Third Battle of Winchester, the fight at Fisher’s Hill and Port Republic, the Battle of Tom’s Brook (the worst defeat suffered by the Confederate cavalry in Virginia during the entire Civil War), and in the Battle of Cedar Creek, among others. He was promoted to brigadier general on December 19, 1864. On May 3, 1865, he disbanded the last organized Confederate forces at Lexington, Va., after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Worried about being charged with treason, Jackson fled to Mexico, but soon returned to the United States and gave his parole in Brownsville, Texas on July 26, 1865. He returned to West Virginia, but learned that ex-Confederates had been banned from practicing law in the Union’s newest state.

Forbidden to practice law in his native state, West Virginia, Jackson, with his wife and children, instead settled in Louisville, Kentucky, where he resumed his pre-war legal career. He soon attained prominence in the local legal community, and in 1872 he was appointed Judge of the Jefferson Circuit Court. Based on a sterling reputation as a stern, fearless but eminently fair judge, he was regularly re-elected to that office until his death from Bright’s Disease on March 24, 1890. His judicial career was distinguished by high moral courage, as well as professional ability, and he was regarded as one of the leading jurists of Kentucky. “Judge Jackson was always noted for his fastidious dress, polished manners and dignified bearing,” recorded his obituary. “Upon the bench he was sternness personified, but in private life a most agreeable gentleman and of an exceedingly social nature. His form was tall and his features clean cut and remarkably handsome.”

Forbidden to practice law in his native state, West Virginia, Jackson, with his wife and children, instead settled in Louisville, Kentucky, where he resumed his pre-war legal career. He soon attained prominence in the local legal community, and in 1872 he was appointed Judge of the Jefferson Circuit Court. Based on a sterling reputation as a stern, fearless but eminently fair judge, he was regularly re-elected to that office until his death from Bright’s Disease on March 24, 1890. His judicial career was distinguished by high moral courage, as well as professional ability, and he was regarded as one of the leading jurists of Kentucky. “Judge Jackson was always noted for his fastidious dress, polished manners and dignified bearing,” recorded his obituary. “Upon the bench he was sternness personified, but in private life a most agreeable gentleman and of an exceedingly social nature. His form was tall and his features clean cut and remarkably handsome.”

“A man more highly respected or more ably endowed never occupied the seat. He has been an ideal Judge-stern and impartial in enforcing the law, but with a kind heart beneath his severity, ever prompting him to be merciful. He is a man of great personal courage, and never shrunk from the performance of his duty, under the most trying circumstances,” claimed the Parkersburg, West Virginia newspaper a few days before his death. “In private talks he is as genial and courteous as he is dignified. His face is a splendid Roman face, and is an index of a splendid Roman character. His friends could never do enough for him and his enemies pay tribute to his nobility and worth.”

Mudwall Jackson was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. When his wife died, she was buried alongside him, and the two rest under a handsome rose-colored granite monument.

While William L. Jackson may not have been a great battlefield commander, he was, by all accounts, a good man and an excellent jurist. And he is worth remembering if for no other reason than for his magical nickname of “Mudwall.” Here’s to Mudwall Jackson, forgotten Confederate cavalryman.

Scridb filterSince I’ve been asked to report these things more often, I will try to remember to do so. Details, such as time and place, for each event are available by clicking on the link provided for each program.

Later this month, I have two Civil War Roundtable appearances, which are my last two of the year. On Wednesday, October 19, 2011, I will be presenting to the Civil War Forum of Metropolitan New York. The topic for that talk is Ulric Dahlgren’s short but controversial life.

The next night, October 20, I will be speaking to the Civil War Roundtable of Fairfield County, Connecticut, which meets at the Stamford Historical Society. The topic there will be an old favorite, Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg.

On November 16, I will be doing a presentation to the Ross County Historical Society in Chillicothe, Ohio. That talk will be titled “The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command.”

I hope to see some of you at one or more of these programs!

By the way, this is the 1,200th post that I’ve done since this blog began in September 2005. As always, I remain grateful for your continued support and for taking the time to visit my little corner of the Internet.

Scridb filterLest we lose sight of Lost Cause and neo-Confederate ideology, I highly recommend taking a few minutes of your time and read the excellent and though-provoking post on Rea Redd’s blog today. Both Rea and David Blight nail it.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”–George Santyana, The Life of Reason, Volume 1, 1905

Scridb filterThis past weekend was one of my favorite events, the annual Middleburg Conference on the Art of Command in the Civil War, hosted by the Mosby Heritage Area Association. This was the 14th annual conference, and my fourth as a presenter. More than 90 attended, meaning that this year’s conference was the largest yet for the MHAA, which is a tribute to Childs Burden (the man who is responsible for the conference and the president of the MHAA) and the rest of his officers and board, all of whom do a great job. All proceeds benefit the good work interpreting the area being done by the MHAA.

This year’s program was titled “Cavalry to the Field!” and dealt with mounted operations in the Eastern Theater. The best thing about it was the gathering of the cavalry guys, as I like to call our merry little band of brothers. It’s been something like 14 years since we were all together at a conference last, and I really enjoyed having the opportunity to get caught up with all of them. On the program were old friends Bud Hall, Horace Mewborn, Bob O’Neill, Marshall Krolick, Bruce Venter, and Bob Trout. A number of the attendees, including Jim Morgan, Jim Nolan, and a handful of others, are also old friends, and it was also great to see them. Also on the program was J.E.B. Stuart, IV, who gave a really interesting talk on his great-grandfather’s service in the west during his years in the Regular Army before the Civil War.

I did a talk based on our book Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. I’ve done that talk dozens of times, but this was the first time that I’ve ever given it with someone actually named Jeb Stuart in the room, and let me tell you, it was a little intimidating to do so. Luckily, I had chatted with Colonel Stuart, who is not only a former Regular Army officer, but also a true gentleman, and knew that he didn’t disagree with my interpretation of those events. Nevertheless, it was intimidating.

I did a talk based on our book Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. I’ve done that talk dozens of times, but this was the first time that I’ve ever given it with someone actually named Jeb Stuart in the room, and let me tell you, it was a little intimidating to do so. Luckily, I had chatted with Colonel Stuart, who is not only a former Regular Army officer, but also a true gentleman, and knew that he didn’t disagree with my interpretation of those events. Nevertheless, it was intimidating.

This photo is of the panel discussion at the end of the day on Saturday. Bud Hall is beside me, and because I was leaning forward to answer a question, he can’t be seen there. From left to right: Horace Mewborn, Bob Trout, Marshall Krolick, Jeb Stuart, IV, Bob O’Neill, me, Bud Hall (although you can’t see him next to me), Bruce Venter, and the fellow at the lectern is Childs Burden. If you want to see this photo (or the other two) in a larger version, just click on the photo.

This photo is of the panel discussion at the end of the day on Saturday. Bud Hall is beside me, and because I was leaning forward to answer a question, he can’t be seen there. From left to right: Horace Mewborn, Bob Trout, Marshall Krolick, Jeb Stuart, IV, Bob O’Neill, me, Bud Hall (although you can’t see him next to me), Bruce Venter, and the fellow at the lectern is Childs Burden. If you want to see this photo (or the other two) in a larger version, just click on the photo.

Sunday featured a full-day tour of the Brandy Station battlefield. Naturally, Bud Hall led the tour, but a number of us helped. I had responsibility for one of the buses, and Mike Block, a former member of the board of trustees of the Brandy Station Foundation, was with me. Mike and I have led several tours of the battlefield previously, and we work well together. Bruce Venter, who is the world’s only known fan of Judson Kilpatrick, also pitched in when we visited Rose Hill, the Stevensburg house that served as Kilpatrick’s headquarters during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac in 1863-1864. There were about 75 people on the tour, and we needed an extra bus to accommodate the entire crowd.

Bud asked me to discuss the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry’s heroic charge into the teeth of the Confederate horse artillery on the St. James Church plateau during the morning phase of the fighting on the Beverly Ford road. That’s me describing the action at St. James Church.

Bud asked me to discuss the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry’s heroic charge into the teeth of the Confederate horse artillery on the St. James Church plateau during the morning phase of the fighting on the Beverly Ford road. That’s me describing the action at St. James Church.

This was my first visit to the Brandy Station battlefield since May, when Lake Troilo was at its worst. I knew that some efforts have been undertaken to begin to try to correct the terrible harm done to the battlefield by Tony Troilo, but I hadn’t seen the state of things again until yesterday. The good news is that the dams of Flat Run have been removed and that the pond seems to have pretty well drained. However, the draining of the pond doesn’t restore the earth that was turned in order to build the dams and dig the pond, nor can it ever. While Troilo is under orders to restore things, we will never know how many artifacts and final resting places of dead soldiers were disturbed by this process.

The final stop of the tour was on a parcel of land owned by the Brandy Station Foundation and which overlooks Lake Troilo and the southern face of Fleetwood Hill. While we were there, Bud told the whole sordid tale of the construction of Lake Troilo and the complete and utter abandonment of its duty to protect the battlefield by the president and board of directors of the Brandy Station Foundation. The attendees–many of whom are well-heeled major donors to battlefield preservation efforts–were as horrified to learn of the betrayal by the BSF of its duty to protect the battlefield as we were when it first happened.

At the end of the day, it seems like the only people who think that the BSF’s non-handling of this situation is appropriate and acceptable are the ones who betrayed the trust reposed in them to serve as stewards of the battlefield. That speaks volumes. However, the ones responsible not only refuse to do the right thing by resigning, they refuse to acknowledge that they were wrong about this situation. I guess the next time a developer comes along, the BSF will welcome him or her with open if the check has enough zeroes after it, like what happened with the Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association and the casino promoters.

Nevertheless, the conference was an overwhelming success, and I was honored to have played a small role in it. I look forward to being invited again soon. And for those who have never attended this excellent program, please consider doing so, as you will not be disappointed.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like