Category:

Research and Writing

I just found a very interesting tidbit….

A certain Gettysburg licensed battlefield guide has stated a theory that Farnsworth’s Charge occurred a mile or so away from where traditional accounts place it. I’ve always maintained that that theory is just that–a theory. J David Petruzzi and I wrote a very lengthy essay rebutting this theory that appears as an appendix to the second edition of my book Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions, the content of which was largely based on the words and comments of the veterans of the battle.

I just found a new one. In this one, a private of the Fifth Corps, wrote, “During this time the Union cavalry made its appearance on our left in rear of Hood’s division. Kilpatrick sent Farnsworth forward across Plum Run. He charged the infantry, and endeavored to capture their reserve artillery and supplies. Though unsuccessful, and its leader and many of his men were killed and many made prisoners, yet it proved a useful diversion. It told upon the final issue of the battle by preventing Longstreet from reinforcing the rebel centre, to assist in the final and main attack which Lee was maturing. It also spoiled the execution of a plan Hood had formed to capture our supply trains.” The source for this is Warren Lee Goss, Recollections of a Private. A Story of the Army of the Potomac (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1899), pp. 211-212.

This demonstrates that the other theory is just plain wrong–Plum Run flows nowhere near where that theory places the charge. If, indeed, Farnsworth’s Charge crossed Plum Run as Goss contended, it had to have occurred where the traditional interpretations of the battle place it. This map shows the course of Plum Run, which empties into Rock Creek far from the southern end of the battlefield (to see a larger version of this map, simply click on it). That alternate theory says that the charge happened along the Emmitsburg Road near where Wesley Merritt’s Reserve Brigade fought. Plum Run is nowhere near there.So much for that other theory…

Scridb filterThere were many important early chroniclers of the American Civil War. Most have been long forgotten in the tidal wave of books on the Civil War that has marked the last 150 years. Few were more important than Bvt. Maj. Gen. John Watts DePeyster of New York. DePeyster wrote a number of very influential works on the war, including treatises on tactics and a vigorous defense of Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles’ conduct during the Battle of Gettysburg. DePeyster was very influential in his time, but he is almost completely forgotten by history today. To learn more about American History, visit this post about the “forgotten generation”.

John Watts DePeyster was born on March 9, 1821, the son of Frederic de Peyster, a wealthy and powerful New York lawyer, investor and philanthropist. His great-great grandfather, Abraham de Peyster, was an early mayor of New York City, as was Abraham’s brother Johannes. His grandfather was a nephew of Lt. Col. Arent de Peyster, commandant of the British garrison at Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Detroit controlled during the American Revolution. John Watts DePeyster was a first cousin of Civil War hero Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, the one-armed, swashbuckling general killed at Chantilly on September 1, 1862. He was also a nephew of the legendary dragoon, Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny.

DePeyster inherited vast wealth at a young age, more than one million dollars by the time he was twenty-one. He studied law at Columbia College, although he did not graduate on account of his poor health. He became an invalid at a young age due to a heart affliction he developed during service as a volunteer firefighter with the No. 5 Hose Carriage during his collegiate years, including a major fire in 1836 that caused his health problems. He helped to organize the New York Police Department and the Fire Department of New York.

DePeyster married Estelle Livingston (1819-1898) on March 2, 1841. They had five children: John Watts De Peyster was born 2 December 1841 and died 12 April 1873), Colonel Frederick De Peyster , who was born 13 December 1842 and married Mary Livingston, Estelle Elizabeth De Peyster Toler, (James B Toler), who was born 1844 and died 12 December 1889, Colonel Johnston Livingston De Peyster, who was born 14 June 1846 and married Julia Anna Toler and Maria Livingston De Peyster (born7 July 1852 and died 24 September 1857).

In 1845 he entered state service in New York and was soon named colonel of a militia regiment. The consistently poor state of his health prohibited him from commanding troops in the field. He served as state Judge Advocate General and then as Adjutant General, holding the rank of brigadier general, until he resigned his commission in 1855 after a conflict with the Governor of New York. He traveled extensively through Europe as a military observer, and implemented many reforms that modernized the militia for the upcoming conflict as result of his travels. He continued to serve in an administrative capacity throughout the war after his efforts to obtain a field commission.

In 1861, DePeyster went to Washington, D.C., to solicit a commission as a brigadier general in the Regular Army and offered to raise two regiments of artillery, which he felt best suited his expertise and physical condition. However, New York had already raised its recruitment quote of 75,000 men, so he met with no interest. Rebuffed, he returned home to New York. In June 1863, just before the Battle of Gettysburg, he turned down a commission as a colonel of cavalry offered to him by prominent New York Senator Ira Harris on behalf of Generals Joseph Hooker and Alfred Pleasonton—Pleasonton, a known careerist, may have thought that the wealthy DePeyster’s social connections could have helped his career.

All three of DePeyster’s sons served in the Union armies during the Civil War. His eldest son and namesake, John Watts DePeyster, Jr., served as an aide-de-camp and as an artillery commander with the Army of the Potomac and received a brevet to brigadier general of volunteers. His middle son, Frederic DePeyster, III, was a colonel and a regimental surgeon, and his youngest son, Lt. Johnston DePeyster, commanded a battery of artillery and received credit for hoisting the first Union flag to fly over Richmond in April 1865.

He penned a well-respected treatise titled New American Tactics that was serialized in The Army and Navy Journal that advocated using skirmish lines instead of main lines of battle, a revolutionary theory for the times. In spite of his ill health, DePeyster still achieved the rank of brevet major general of the New York State Militia in 1866. After the war, he was active in the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, a veterans’ organization for former Union officers.

DePeyster and his family resided on an estate–Rose Hill–located in Tivoli, Duchess County, New York. He was a prolific writer and an accomplished military historian. After the Civil War, he was known as “America’s foremost military critic.” In that capacity, he published hundreds of pieces, including, perhaps, approximately fifty under the pseudonym “Anchor.” One commentator noted DePeyster’s “keen eye for topography, his long and still unceasing military education, his uncommon memory, his power of description and his opportunities for using his abilities constitute him the only as well as the first military critic in America.” DePeyster “rejoiced in overriding conventionalities and often showed strong bias, particularly in defense of a familial connection, but his writings show exceptional knowledge of military history and science.” This kind of erudition comes through plainly in DePeyster’s writings.

He strongly supported his fellow Empire Stater and close friend, Daniel E. Sickles, and, using the “Anchor” pen name, vigorously defended Sickles’ role at the Battle of Gettysburg. He also defended Hooker’s role leading up to the battle, and harshly criticized the role of the XI Corps at Chancellorsville. He praised the generalship of George H. Thomas, helping to establish Thomas as one of the pantheon of great captains of the Civil War. In numerous articles, including The New York Times and various scholarly journals, he correctly predicted the coming of the Franco-Austrian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

DePeyster was actively involved in alumni activity of his old friend Sickles’ former command, the III Corps. An organization called the Third Army Corps Union was formed as a beneficial society for the wives and children of veterans of the III Corps, and DePeyster helped write its history. Long his cousin’s advocate, DePeyster also wrote a fawning biography of Kearny. He was particularly interested in the Battle of Saratoga, and donated a memorial called the “Boot Monument” which commemorates Benedict Arnold’s heroic role and wounding in the battle (although he is not mentioned by name, and the memorial depicts only his boot), in 1887. DePeyster also authored numerous other well-regarded works of a military nature.

Because DePeyster enthusiastically defended Sickles’ conduct at Gettysburg, he took up his pen to attack George Gordon Meade. He penned a number of articles under the “Anchor” anonym that were published in a veterans’ publication in 1867, after the end of the war, and well after the release of the Joint Committee’s report. DePeyster then bundled them and published them under his real name in book format under the title The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War, or Slaveholders’ Rebellion. He devoted half of his book to his criticisms of Meade’s conduct of the pursuit of Lee’s army.

His list of publications included Life of Field Marshal Torstenson (1855), The Dutch at the North Pole (1857), Caurausius, the Dutch Augustus (1858), Life of Baron Cohorn (1860), The Decisive Conflicts of the Late Civil War, or Slaveholder’s Rebellion (1867), Personal and Military History of General Philip Kearny (1869), The Life and Misfortunes and the Military Career of Brig.-Gen. Sir John Johnson (1882), and Gypsies: Some Curious Investigations, Collected, Translated, Or Reprinted from Various Sources (1887). He also contributed to numerous other books, biographies, publications, and articles.

After the war, DePeyster became a major real estate developer in his hometown of Tivoli, New York. In 1892, he constructed a large Methodist church that remains an active congregation to this day. He refurbished an old school house and turned into an industrial school for girls. Then, in 1895, he constructed a very large brick firehouse for the local fire department which remained in use until 1986. He eventually had a falling out with Tivoli’s mayor–his own son, Johnston–and DePeyster barred the mayor from entering the building, forcing the village government to relocate to another building until the old firehouse was restored in 1994, when the village government again too up residence in the firehouse.

A 1908 newspaper article stated:

Gen. John Watts De Peyster, the millionaire philanthropist, is living the life of a recluse at Rose Hill, the ancestral seat of his family, at Tivoli. He is reputed to be worth millions, much of his property consisting of real estate in the city of New York, which has been in possession of his family over a century. He had isolated himself from his kindred and it is believed will give his fortune at his death to the institutions he has founded.

Years before the death of his wife, the general and Mrs. De Peyster lived apart and Col. Johnson L. De Peyster, the general’s only son still living, lost his father’s friendship by espousing his mother’s cause. Father and son did not speak or hold any communication with each other, although their two estates adjoined. Gen. De Peyster was persistent in his estrangement from his son even up to the son’s death. He did not visit him or inquire about him when he was ill. When Col. De Peyster died in May, two years ago, the grim old general closed the gates of Rose Hill.

A delegation of villagers who wished permission to drape De Peyster hall in memory of the colonel, who was very popular in Tivoli, was turned away without an audience. Gen. De Peyster refused to attend his son’s funeral. His sole concession was to offer to the widow the keys of the family vault. The tender was ignored and Col. De Peyster’s remains were laid at rest in the vault of Johnston Livingston, an uncle of the colonel’s on his mother’s side.

In 1901, he donated several thousand books and maps to the Smithsonian Institution, one of many major philanthropic gifts he gave over the court of his life. He donated the money to construct the first library at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and donated one of the largest collections of rare books about European military history, a collection gathered while he traveled Europe to research a biography of Napoleon he published in 1896. He also served as Vice President of the American Numismatic Society. Post #71 of the New York G.A.R. in Tivoli, New York was named for him.

De Peyster died in 1907 of natural causes at a family residence in Manhattan. He was buried in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Cemetery in Tivoli. He willed his massive manor house Rose Hill to a local Children’s Home.

DePeyster’s vigorous defense of Sickles and his aggressive attacks on George Gordon Meade’s conduct of the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia after the Battle of Gettysburg played a major role in relegating Meade to under appreciated obscurity in the years after the American Civil War, which makes DePeyster worthy of study.

Scridb filter With many thanks to Dave Roth, the publisher, for giving me permission to reprint it here, here is Rob Grandchamp’s extraordinary review of “The Devil’s to Pay”: John Buford at Gettysburg. A History and Walking Tour that appears in the current issue of Blue & Gray Magazine. I’m humbled by such a wonderful review, which is the finest review any of my books has ever gotten.

With many thanks to Dave Roth, the publisher, for giving me permission to reprint it here, here is Rob Grandchamp’s extraordinary review of “The Devil’s to Pay”: John Buford at Gettysburg. A History and Walking Tour that appears in the current issue of Blue & Gray Magazine. I’m humbled by such a wonderful review, which is the finest review any of my books has ever gotten.

Award winning historian Eric Wittenberg, who has had a lifelong fascination with Union General John Buford, has researched and authored this tome. It combines the sharp research and intellect that he brings to his work, extensive use of primary manuscript sources, as well as the maps and images that Savas Beatie’s works are known for.

Wittenberg begins with a brief biography of Buford and an overview of his First Cavalry Division. The book is heavily illustrated with photographs, and includes many never before seen images. In addition, highly detailed maps throughout the text show the position of Buford’s men in this battle. Arriving in Gettysburg on June 30, 1863 Buford carefully surveyed the ground and determined to hold a series of ridges west of the town in order to delay the Confederates and allow the Union infantry to get into position. Wittenberg notes that Buford’s tactics on the morning of July 1 are still taught to cadets at West Point as a classic example of the use of cavalry (now replaced with wheeled vehicles, but still employing the same concepts).

Much of the book covers Buford’s actions on the first day at Gettysburg. Through a series of breakdowns in Confederate leadership, and with superb use of the terrain and their breechloading carbines, the eight regiments of Buford’s command were able to hold the ground against an overwhelming Confederate offensive. The descriptions of this action are the most detailed and descriptive this reviewer has ever seen. The maps highlight the action, allowing the reader to view the text down to the company and regimental level. In addition, the well placed footnotes allow for further serious scholarship. It is evident that Wittenberg has done his homework, as the book contains many sources not previously seen by historians. Buford’s men held their positions until the I Corps arrived on the field, and continued to support General John Reynolds’ flanks until the corps retreated back to Gettysburg.

While most books that narrate the story of Buford’s men at Gettysburg end with his division being relieved at the end of the First Day, this book does not. On the morning of July 2, one of the brigades supported the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters and the 3rd Maine in a reconnaissance in force near Pitzer’s Woods on Seminary Ridge. This engagement is often overlooked, but Wittenberg provides a detailed overview of the brief fight at Pitzer’s Woods, which was the opening of the battle on the southern part of the line on the Second Day. After this engagement, army commander General George G. Meade wisely sent Buford’s worn out division back to Westminster, Maryland to guard the supply train and refit.

The main part of the book ends with a historiography of Buford’s legacy and his role at Gettysburg. Several important appendices are also present, including one on the Buford monument at Gettysburg, a driving tour of positions associated with Buford’s command, and a discussion about the long held thought that Buford’s men were armed with Spencer repeaters, rather than single-shot breechloading carbines, at Gettysburg. Wittenberg, through deep research, has finally determined that the command was not armed with Spencers until the fall, and that Buford’s eight regiments carried a miscellaneous assortment of carbines.

In conclusion, this book is typical of what we have come to expect from Wittenberg: meticulously researched, superbly illustrated, and well written. While many books have been written about the early morning fighting at Gettysburg on July 1, 1963, this is the first book that has focused solely on the very important role that John Buford and his First Cavalry Division played in the fighting. While often an unsung hero of the battle, this book has brought Buford’s role in the action back to life. It is one of the better books to come out of the Civil War Sesquicentennial. “The Devil’s to Pay” is an exceptional read and must-add to any Civil War collection.

It simply does not get any better than that, I am very grateful to Rob for his incredibly kind words about my labor of love. That is, without question, the single best review one of my works has ever received.

I do need to correct Rob’s statement about when Buford’s command might have been armed with Spencer repeaters. Rob incorrectly states that the First Cavalry Division was armed with Spencer carbines in the fall of 1863. The Spencer carbine only went into mass production in September 1863, and there were not sufficient quantities of them available to distribute until the winter of 1863-1864. When the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps took the field in the spring of 1864, it was largely armed with Spencers, but not before that time.

Scridb filter One of my favorite projects of mine, and one of the projects I am most proud of, is my 2009 biography of Ulric Dahlgren, Like a Meteor Blazing Brightly: The Short but Controversial Life of Colonel Ulric Dahlgren. The book has been universally well received. Unfortunately, the publisher, Edinborough Press, lost its distributor, and even though I have always had inventory of them, it has not been available through Amazon or otherwise for quite a while now. Sadly, Edinborough’s efforts to obtain a new distributor have not been successful.

One of my favorite projects of mine, and one of the projects I am most proud of, is my 2009 biography of Ulric Dahlgren, Like a Meteor Blazing Brightly: The Short but Controversial Life of Colonel Ulric Dahlgren. The book has been universally well received. Unfortunately, the publisher, Edinborough Press, lost its distributor, and even though I have always had inventory of them, it has not been available through Amazon or otherwise for quite a while now. Sadly, Edinborough’s efforts to obtain a new distributor have not been successful.

Dan Hoisington, the publisher at Edinborough, has graciously agreed to revert the publication rights to the book back to me, and I have struck a deal with my favorite publisher, Savas-Beatie, for the book to become generally available again. One of the many reasons why I love working with Savas-Beatie is its really outstanding distribution network, so the prior problem should not arise again.

In very short order, Savas-Beatie will make an eBook version of it available in all digital formats (Kindle, iPad, Android, Nook, etc.) for download. A 6 x 9 trade paperback of the book will be available later this year at a price yet to be determined. Once I know the date and the price, I will let everyone know.

In the interim, hardcover copies of the original edition of the book will continue to be available through me for the original price of $29.95, and are available either signed or unsigned. Please contact me directly to purchase those.

And Ted Savas and I are working on bringing back another old favorite of mine that has been out print for far too long. Stand by for important news on that soon…..

Scridb filter On December 3, I traveled to Pittsburgh to film an episode (my second) of Pennsylvania Cable Network’s “PA Books” programs on The Devil’s to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg. I’ve been advised as to the air dates for my interview, which are: The program will air on Sunday, January 4th at 7PM. Additionally, it will air as part of PCN’s “Best of 2014” block on Monday, December 29th (2014) at 1PM. I hope some of my Pennsylvania friends will check it out on your local cable networks! It will also be available for download as a podcast on PCN’s website once the program airs on PCN.

On December 3, I traveled to Pittsburgh to film an episode (my second) of Pennsylvania Cable Network’s “PA Books” programs on The Devil’s to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg. I’ve been advised as to the air dates for my interview, which are: The program will air on Sunday, January 4th at 7PM. Additionally, it will air as part of PCN’s “Best of 2014” block on Monday, December 29th (2014) at 1PM. I hope some of my Pennsylvania friends will check it out on your local cable networks! It will also be available for download as a podcast on PCN’s website once the program airs on PCN.

Time for some shameless self-promotion. Over the weekend, I signed off on the page galleys for my newest book, The Devil’s to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg. A History and Walking Tour. The file has been sent to the printer, and in about five weeks, my publisher, Savas Beatie, LLC, will have books.

Time for some shameless self-promotion. Over the weekend, I signed off on the page galleys for my newest book, The Devil’s to Pay: John Buford at Gettysburg. A History and Walking Tour. The file has been sent to the printer, and in about five weeks, my publisher, Savas Beatie, LLC, will have books.

This is, in many ways, the culmination of my life’s work. I began researching what started out as a bio of John Buford not long after Susan and I got married din 1992. This study of John Buford at Gettysburg has been percolating all that time. The book will feature 17 of Phil Laino’s excellent maps (including two that have never before been mapped) and more than 80 illustrations (including three images that have never before been published). I’m really excited to finally see this in print after all of these years.

The book will sell for $32.95 plus $3.95 for shipping. I will also be offering a special collector’s edition that contains a special signed and numbered bookplate that will make for a perfect gift for $75.00. Shipping is free for the special edition. I am taking pre-orders for signed copies beginning tonight. Those interested can pay one of three ways: by PayPal, by credit card, or by check. If you wish to pay using PayPal, please use the email address eric_at_civilwarcavalry.com (I have stated the address that way so that bots don’t pick it up as easily). If you wish to pay by credit card, please send me an email to that address, and include your name, address, credit card number, expiration date, CVV on the back (the three-digit or four-digit code), and the billing address. If you want to pay by check, please send me an email at that address, and I will provide you with a mailing address.

Thank you for your interest in my work, and I hope everyone enjoys the book, which has been a LONG time coming.

Scridb filterI received the following challenge:

List 10 books that have stayed with you in some way. Don’t over think it. They don’t have to be the “right” books or great works of literature, just books that have impacted you in some way.

So, here goes, in no particular order:

1. The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War. This was the one that started it all for me. Bruce Catton’s wonderful prose and THE coolest maps ever made.

2. William Manchester’s marvelous The Arms of Krupp, 1587-1968. My master’s thesis was a direct result of having read this book.

3. Carlo D’Este, Patton: A Genius for War. Simply put, THE finest military biography that I have ever read.

4. Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command. An epic study that not only taught me a lot about the Confederate side of the Civil War, it also introduced me to the Lost Cause.

5. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit: There and Back Again. Yep, I’m a nerd. This proves it.

6. Cornelius Ryan, A Bridge too Far. This epic study of the wretched, miserable failure that was Operation Market Garden is one of the finest campaign studies ever written.

7. Alan T. Nolan, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. This groundbreaking book directly led to the publication of one of my books.

8. Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels. Full of factual errors but one of the finest pieces of historical fiction ever written, this book was the introduction to the Civil War for many a person.

9. John Hennessy, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas. This is THE best Civil War campaign study I have ever read, and I aspire to doing as well some day.

10. Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Moses was the most powerful man in New York, but his ego and downfall brought about the bankruptcy of New York in the 1970’s. This epic biography taught me the art of biography.

There are, of course, many, many other worthy candidates for inclusion on such a list–in fact, limiting the list to ten entries really unreasonably limits things. But these are the ten that come to mind without overthinking it, and I think that this list is a worthy one.

Feel free to leave your own lists here in the comments. It should make for some interesting discussion.

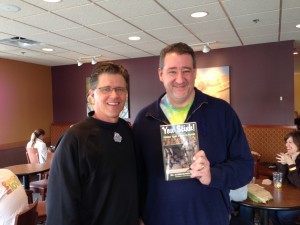

Scridb filter Shown in the photo with me is my friend David Raymond, who wrote the foreword to You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players. Unless you’re either a long-time, die-hard Phillies fan, or a die-hard fan of the University of Delaware’s football program, the likelihood is that you don’t know who Dave is. Click on the photo to see a larger image.

Shown in the photo with me is my friend David Raymond, who wrote the foreword to You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players. Unless you’re either a long-time, die-hard Phillies fan, or a die-hard fan of the University of Delaware’s football program, the likelihood is that you don’t know who Dave is. Click on the photo to see a larger image.

The other photo is Dave’s alter ego, the Phillie Phanatic. Dave was the original Phillie Phanatic. He wore the green suit from the time that the character was introduced in 1978 through the 1993 World Series season, and then he passed the suit on to the current Phanatic’s Phriend, Tom Burgoyne. Dave then founded Raymond Entertainment Group, where his self-bestowed (but very accurate) title is Emperor of Fun and Games.

The other photo is Dave’s alter ego, the Phillie Phanatic. Dave was the original Phillie Phanatic. He wore the green suit from the time that the character was introduced in 1978 through the 1993 World Series season, and then he passed the suit on to the current Phanatic’s Phriend, Tom Burgoyne. Dave then founded Raymond Entertainment Group, where his self-bestowed (but very accurate) title is Emperor of Fun and Games.

One of the products delivered by the Raymond Entertainment Group is fun. And by fun, I mean The Fun Department. Since 2006 The Fun Department has been delivering Fun to corporations throughout the tri-state area. “We are out to make corporate America smile one face at a time”, says Dave. The Power of Fun is a message that Dave delivers everyday with Raymond Entertainment and The Fun Department. Dave regularly gives his Power of Fun speech to groups in the hope of teaching them that bringing joy, laughter and fun to every day life is not only therapeutic, it is good business. After years of delivering this message in person, Dave decided that it was time to deliver the message of Fun to the masses by writing a book.

And then Dave asked me to be his co-author for the project, which will be called The Power of Fun. We’re still mapping out the contents of the book and precisely what it will cover, but Dave and I both think that this collaboration will be great fun, and that it is important for us to preach the gospel of Fun.

And so, I will be tackling a project very much unlike anything else that I have ever done. Life is all about challenging oneself and stretching one’s limitations. There is much to learn by this project, and there is much for us to teach. I’m greatly looking forward to working with Dave to spread the word about the Power of Fun. Please stay tuned for periodic updates.

In case any of you are interested in booking Dave for a presentation on the Power of Fun, you can reach him by clicking here.

Scridb filter The photo at the left is of Brig. Gen. John Buford, whom I freely acknowledge is my single favorite figure of the Civil War. I’ve long harbored a fascination with Old Steadfast, as his men called him, and have had four articles on his role in the Gettysburg Campaign published in Gettysburg Magazine. Three of my books also touch on Buford’s career heavily. But I’ve never done a monograph on Buford at Gettysburg, which is the topic that got me started on him in the first place.

The photo at the left is of Brig. Gen. John Buford, whom I freely acknowledge is my single favorite figure of the Civil War. I’ve long harbored a fascination with Old Steadfast, as his men called him, and have had four articles on his role in the Gettysburg Campaign published in Gettysburg Magazine. Three of my books also touch on Buford’s career heavily. But I’ve never done a monograph on Buford at Gettysburg, which is the topic that got me started on him in the first place.

About three weeks ago, I realized that I have published something book-length on every major cavalry action that took place north of the Mason-Dixon Line during the Gettysburg Campaign but one: John Buford’s actions at Gettysburg. I am now in the process of correcting that oversight. I am doing a monograph on Buford’s role at Gettysburg, June 30-July 2, 1863. It will include 16 of Phil Laino’s excellent maps, a lot of photographs (including some rare, seldom-seen images), and a walking/driving tour with GPS coordinates. There will be three appendices: one addressing the myth of the Spencers, another discussing whether Buford’s defense was a defense in depth or something else, and one addressing the question of whether Lane’s Brigade formed square to defend against a feinted mounted charge by Buford’s two brigades at the end of the first day’s fighting at Gettysburg. J.D. Petruzzi will do an introduction for the project for me. I don’t expect it to be a terribly long book, but it will be jam-packed with useful information.

I have been researching this for more than 20 years, and I am confident that this is going to be a quality project. In many ways, it’s like visiting with an old friend, and I’m enjoying coming back to what has always been my first love with respect to the Battle of Gettysburg. Sit tight–I will update as to progress.

And, in a few days, I will have an announcement about another fun project that has nothing whatsoever to do with the Civil War. Stay tuned…..

Scridb filter This article appeared in the August 13, 1865 edition of the New York Times and is the earliest account of the fascinating story of how Ulric Dahlgren’s remains were secretly recovered and taken to a safe spot near Atlee’s Station, Virginia.

This article appeared in the August 13, 1865 edition of the New York Times and is the earliest account of the fascinating story of how Ulric Dahlgren’s remains were secretly recovered and taken to a safe spot near Atlee’s Station, Virginia.

COL. ULRIC DAHLGREN.; Curious Story Regarding the Disposition of his Remains.

Published: August 13, 1865From the Richmond Bulletin, Aug. 5.

The month of March, 1864, is memorable in Richmond for one of the grandest Union raids that up to that time had menaced the Confederate capital — a raid which was the immediate precursor of Gen. GRANT’s famous campaign from the Wilderness to James River. The history of this raid is too familiar to the minds of all of our readers to make necessary any recapitulation of it, even if it comported with our space. It is known that COL. DAHLGREN, after the attack on Richmond on Tuesday, the 1st of March, did not succeed in forming a junction with Gen. KILPATRICK, and while passing through King and Queen Counties, toward Gloucester Point, was killed, on the night of Wednesday, March 2, near Walkerton. It is also known that his body was brought to Richmond, but what disposition was made of it by the Confederate authorities was kept a mystery at the time, and the facts, even to this day, have never been published. We purpose to give them to the public for the first time, vouching for their entire authenticity.

When intelligence was received in Richmond of the death of Col. DAHLGREN, messengers were sent to bring it to the city for identification. It reached the city on Monday, March 7, by the York River Railroad, and laid during that day at the depot, where it was examined by large numbers of persons. His death had been caused by a gun-shot wound in the head. The little finger of one hand had been cut off on the field where he fell by some one anxious to secure, with the least trouble, a valuable diamond ring. That night the body was carried to Gen. ELZLY’s office, in Belvin’s block, and the next day. having been placed in a common pine coffin, of the kind then used for the burial of soldiers, which in turn was placed in a box, was transferred to the Oakwood Cemetery, a mile east of the city. The hearse used on this occasion was a four-mule street wagon, and the attendants consisted of a Confederate officer of inferior rank and two soldiers. Arriving at Oakwood, which was the burial place or all soldiers who died at Chimborazo, Howard’s Grove, and other hospitals in the eastern portion of the city and suburbs, the negro grave-diggers and other attendants about the cemetery were driven off and ordered to absent themselves until notified that they might return. One of the negroes, now living in the city, having his curiosity excited, secreted himself in the woods near by determined to see what was to be done. The two soldiers dug a grave, placed the box in it and covered it up. They then shouted to recall the attendants of the cemetery, and getting into the wagon, returned to the city. The only circumstance in the proceedings that struck the negro as unusual was the mystery observed and the circumstance of the box, no corpse ever having been brought there before except in a pine coffin; but there having been a great deal of talk as to what was to be done with the body of Col. DAHLGREN, he at once decided that this could be no other than the corpse of that officer. He, however, kept his opinion to himself at the time.

The question, what had been done with the body of DAHLGREN? was the subject of inquiry and conversation for many days in Richmond, to be revived from time to time up to the day of the evacuation. And there were many stories on the subject — that it had been burnt, sunk in the river, &c. A city paper of that day announced, with a solemn and knowing air, that it would never be found until the trump of doom should sound. A number of Union men of the city, believing it possible that it might be recovered, were anxious to secure and preserve it for the family of the deceased. Prominent among them was Mr. F.W.E. LOHMAN, a grocer, doing business near the New Market. Mr. LOHMAN at once began his inquiries and investigations — which, in the then state of popular feeling, it was necessary to conduct with great caution — determined, at whatever cost and risk, to ascertain its fate. After nearly a month’s patient and untiring inquiry, he, with the assistance of Mr. MARTIN MEREDITH LIPSCOMB, whose business it was to attend the interment of all Union prisoners who died at this post, made the acquaintance of the negro grave-digger, whom we have mentioned as being the sole spectator of the burial of Col. DAHLGREN. They found him at Oakwood, pursuing his regular business. When first approached on the subject, the negro was very much alarmed, and protested he would have nothing to do with the matter. But after repeated assurances by Mr. LIPSCOMB, whom he knew well, that he might rely upon LOHMAN, and that no harm should befall him, he consented, on Mr. LOHMAN’s giving him a hundred-dollar note, to point out the grave. This he did by walking near and casting a stone upon it, while LOHMAN and LIPSCOMB stood at a distance. He was afraid to employ any other method lest he might excite the suspicion of the superintendent of the cemetery or some of the attendants. The grave lay among thousands of those of Confederate soldiers. Subsequently, after a great deal of persuasion and the promise of a liberal reward, the negro agreed to meet Mr. LOHMAN at the cemetery on the night of the 6th of April, at 10 o’clock, and exhume the body.

The appointed night having arrived, Mr. LOHMAN, his brother, JOHN A. LOHMAN, and Mr. LIPSCOMB, started for the cemetery in a cart drawn by a mule. The night was dark and stormy, and well suited to conceal their movements. The party left the city at 9 o’clock, and reached their destination about 10, and there found waiting for them the grave-digger and two assistants. The negroes being assured that all was right, began their work of exhumation, the three white men remaining with the cart outside the inclosure of the cemetery. The heavens were hung with their deepest black; no object ten feet distant could be distinguished, and no sounds broke upon the loneliness of the place save the howling of the winds and the resurrectionist’s spade. Once the mule, snuffing the tainted air of the city of the dead, attempted to break away, but was quickly quieted by a firm hand.

In twenty minutes from the time the negroes began their work they approached the cart, bearing between them the coffin, which, being badly made, fell to pieces as they rested it on the ground. It was then discovered that the body bad not decomposed in any perceptible degree. Mr. LOHMAN satisfied himself of the identity of the corpse by passing his band over it. The little finger, torn off to secure the jewel it bore, and the leg, lost in battle, were missing. He paid the negro with whom he had contracted fifteen hundred dollars, and placing the body in the cart, the party started on their return. The mule, alarmed as animals frequently are when drawing a dead body for the first time, become difficult of management, and with the darkness of the night, made the first part of the expedition one of no little peril. More than one hour was spent in reaching the gaslights of the city on Church Hill. It was part of the plan to convey the body to the house of WILLIAM S. ROWLETT, a Union man, living on Chelsea Hill, a half mile northeast of the city, there to remain until a metallic case could be procured for it. From Church Hill, Mr. LOHMAN drove down Broad-street to Seventeenth-street, thence up Seventeenth-street to its northern terminus, and thence up the hill to Mr. ROWLETT’s, reaching the last place at 2 o’clock on the morning of the 7th of April. Here the body was wrapped in a blanket, and Mr. LOHMAN came to the city in search of a coffin, which he obtained by the aid of Mr. LIPSCOMB. On his way into the city from ROWLETT’s, LOHMAN notified a number of persons of Union sentiments, among whom were several ladies, where the body had been placed, and they hurried out to see it. Several of these persons had seen Col. DAHLGREN while he was exposed at the York River Railroad depot, and immediately recognized the body as his. The metallic coffin having been procured, and the body placed in it, the two LOHMANS, at noon on the 7th, set out with it, concealed, in a wagon loaded with young fruit trees, for the farm of ROBERT ORRICKS, a Union man, living in Henrico, two miles from Hungary Station.

At 4 o’clock that evening they reached ORRICKS’, and buried the body under an apple-tree in a field, avoiding the graveyard for tear of exciting inquiry, which might lead to discovery.

The rest of this story may be told in a few words. ORRICKS, some months after the second burial of Col. DAHLGREN, succeeded in getting through the Confederate lines, and seeking an interview with Com. DAHLGREN, informed him of what had been done to secure the body of his son. The corpse of the soldier laid in this, its second grave, until the evacuation of Richmond, when an order having been sent for it by the War Department, it was again disinterred by the two LOHMANS and sent to Washington.

It has been our object to left the veil of mystery from an obscure and interesting event. In doing so, we have confined ourselves to facts strictly relative to the secret fate of Col. DAHLGREN’s body from the time of its arrival in Richmond, which, until after the capture of the city, remained, to all except the few individuals named by us in the course of our narrative, one of the most impenetrable mysteries of the war. Many Confederate officials knew that the body had been deposited at Oakwood, but they were ignorant to the last that it had ever been removed. It has at length found its last resting place.

This is a largely accurate description of a fascinating event with all of the hallmarks of a great thriller.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like