Month:

March, 2013

Yesterday, I was one of the presenters at the “Gettysburg Before and After” conference put on by Hagerstown Community College. Dennis Frye, the chief historian at the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, gave a very interesting talk on the role that Harpers Ferry played in the Gettysburg Campaign.

Yesterday, I was one of the presenters at the “Gettysburg Before and After” conference put on by Hagerstown Community College. Dennis Frye, the chief historian at the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, gave a very interesting talk on the role that Harpers Ferry played in the Gettysburg Campaign.

Part of what he discussed caught my attention, as it lends some fascinating new insight into the decisions made by the Army of the Potomac’s high command on July 12, 1863. These insights have caused me to re-evaluate some of those decisions. The facts are worthy of presenting here.

By way of background, the Army of the Potomac’s high command considered throwing a pontoon bridge across the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry because the river was too flooded to ford. Doing so could allow Union troops to get around behind the Army of Northern Virginia’s position. The question was when. Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, the army’s chief engineer, had this responsibility. He corresponded with Lt. Col. Ira Spaulding, the chief engineer at Harpers Ferry, who was responsible for the pontoons. The exchange between Warren and Spaulding is worth repeating here.

Here is the first, sent by Warren:

HEADQUARTERS ENGINEERS, ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

July 10, 1863–10:30 a.m.Colonel Spaulding, Engineer,

Harpers Ferry:Sir:

Events are yet to determine where we shall want the bridge across the Potomac and when. Directions will be sent to you in time. I have ordered the transportation train to join you, and to load up to 200 feet of bridge, which we may require on the Antietam Creek.

By order:

G. K. Warren,

Brigadier General of Volunteers, Chief Engineer

O.R. vol. 27, part 3, p. 628. Spaulding responded the next day.

SANDY HOOK,

July 11, 1863–11:45 a.m.General G. K. Warren:

Lieutenant [Ranald S.] MacKenzie is absent with General Naglee, and I opened your dispatch to him.

The Potomac above the railroad bridge at this point has fallen 4 feet within the past forty-eight hours, and is still falling slowly. It is still 4 to 5 feet above the stage of water which renders it fordable here.

The troops of the Engineer Brigade under my command now here have been constantly at work or making forced marches ever since the army left Falmouth, and I take it for granted they are liable at any moment to be called up for extraordinary exertions. Is it desirable that they should be kept incessantly at work here by General Naglee upon work not indispensable to the efficiency and success of the army?

I. Spaulding,

Lieutenant-Colonel, Volunteer Engineers

O.R. vol. 27, part 3, p. 646. The emphasis is mine. This is a critical piece of intelligence. If the river had fallen 4 feet in 48 hours, and it had only another 4-5 feet to drop in order to be fordable, then at the very latest, the river would be fordable within 48 hours, and probably much less if it continued to be dry. In other words, at that rate of dropping, the Potomac would be fordable no later than July 13. And the Williamsport crossings are upriver from Harpers Ferry, meaning that they would fordable before the crossings at Harpers Ferry.

On July 13, as the Army of Northern Virginia was preparing to cross that night, Warren wrote:

HEADQUARTERS ENGINEERS

July 13, 1863–5 p.m.Colonel Spaulding:

We may want a bridge across the river before long. If sending away the 100 men to repair the canal will not interfere with laying the bridge, it is desirable to have it done.

G. K. Warren,

Brig. Gen. of Vols., Chief Engineer, Army of the Potomac

O.R. vol. 27, part 3, p. 672. The pontoon bridge was laid the next day, AFTER the Army of Northern Virginia had already made it to safety across the Potomac. Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg’s Second Cavalry Division had a major engagement with Confederate cavalry at Sandy Hook, near Harpers Ferry, the next day.

There’s some real food for thought here. Specifically, on July 11, Spaulding advised Warren–the Army of the Potomac’s chief engineer–that the Potomac River was dropping and would be fordable no later than July 13, assuming no more rain fell. Once the Potomac could be forded at Williamsport, which is 15 or so miles upstream from Harpers Ferry, the Army of Northern Virginia could cross to safety. This means that Lee could escape unless the Army of the Potomac moved quickly to attack it.

On the night of July 12, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, held a council of war with his officers. Meade was anxious about whether to attack the Army of Northern Virginia’s entrenched positions along the Potomac, the strength of which was obvious to anyone caring to look. Meade, his chief of staff, Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys, and his corps commanders all attended. They included: Gens. James Wadsworth (filling in for an ill Gen. John Newton, temporary commander of the 1st Corps), William Hays (in temporary command of the Second Corps), William H. French (commanding the 3rd Corps after Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles was severely wounded at Gettysburg), George Sykes (5th Corps), John Sedgwick (6th Corps), O. O. Howard (11th Corps), Henry W. Slocum (12th Corps), and Alfred Pleasonton (Cavalry Corps). Also attending were Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, who commanded a division of emergency militia troops that had joined the Army of the Potomac, and chief engineer Warren.

Meade strongly favored an attack on July 13, but he wanted the support of his corps commanders before issuing the orders to do so. Wadsworth, Howard, and Pleasonton favored an attack. So did Warren. Sedgwick, Slocum, Sykes, French, and Hays opposed it. However, none of Humphreys, Pleasonton, or Warren were permitted to vote, meaning that a majority of the commanders with a vote opposed the attack. While Meade could have overridden the vote and could have ordered the attack anyway, he reluctantly took the advice of his commanders, which was to spend the 13th probing the Confederate lines and to attack on the 14th. Nobody knew that Lee’s army would steal away on the night of the 13th and that the general advance of the Army of the Potomac on the morning of the 14th would find the trenches empty and the Confederates gone.

The record fails to indicate whether Warren advised the council of war of the critical intelligence forwarded by Colonel Spaulding–that the Potomac was steadily dropping and would be fordable the next day if the rains continued to hold off. Warren was a conscientious officer, and presumably he did pass on that important piece of information. But we do not know for sure. Had he failed to do so, one cannot help but wonder whether that critical piece of information might have changed the outcome of the July 12 council of war.

Conversely, if Warren did, indeed, pass along that critical intelligence, that makes the vote of the five corps commanders who opposed an attack all the more puzzling. And it also makes Meade’s decision not to override their vote and order the attack anyway all the more perplexing. It is a cliche that councils of war never vote to fight, so the outcome of the July 12 council was somewhat predictable. Another cliche comes to mind: for want of a nail, a kingdom was lost.

In the end, I remain convinced that short of ordering the attack on July 13–an attack that had no guarantee of success, given the incredibly strong position held by the Confederates–there is little, if anything, that Meade could have done to prevent the Army of Northern Virginia from making its escape once the depth of the Potomac River dropped enough for it to become fordable. And, in the end, I cannot fault Meade for not wanting to attack that incredibly strong position–bristling with artillery behind earthworks–without having a better idea of its make-up and without having some idea if there were any weak spots to exploit or particularly strong points to avoid. A good army commander would not make such decisions rashly, and Meade was not a rash man. It’s entirely possible, then, that this critical piece of intelligence might have made no difference whatsoever in the big scheme of things. But it is tantalizing.

This is an incredibly fascinating twist, and it demonstrates how the smallest scrap of information can have far-reaching and unforeseen consequences. Thanks to Dennis Frye for passing this information along.

Scridb filterThis is the 1,300th post on this blog since it began in September 2005. Had anyone suggested that it would still be around and still going strong, I would not have believed it.

1,300 posts is a LOT of posts.

I appreciate all of you. I treasure my interactions with all of you here, which is, in large part, why this blog is still around and still going strong. Thank you for your support in the past, and thank you for your support going forward. And with your continued support, it will continue to go forward….

Thank you to all of you who indulge my rantings. It means more to me than I can say.

Scridb filter Here is another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten Civil War cavalrymen. Today’s profile is of a particular favorite of mine.

Here is another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten Civil War cavalrymen. Today’s profile is of a particular favorite of mine.

Nineteenth Century American cavalrymen were the fighter pilots of their era—devil-may-care, flashy, equally eager to impress the women and eager to seek glory for dashing deeds of courage. When modern students of the Civil War think of cavalrymen, they conjure up images of Jeb Stuart, with his ostentatious ostrich plumes, or of George Custer and his flowing blonde hair and outrageous uniforms. Certainly, the cavalry produced more than its fair share of cads like Earl Van Dorn and Judson Kilpatrick.

However, it also produced some extraordinary soldiers—quiet, modest, competent men who went about their business in an efficient, professional way. This category includes men like John Buford, David Gregg, Wesley Merritt, and Thomas C. Devin on the Northern side, and Wade Hampton, Matthew C. Butler, Lunsford L. Lomax, and Thomas T. Munford on the Southern side. More interested in doing their jobs well than in reaping favorable press clippings, these men avoided the harsh spectacle of the press’s prying eyes.

Theophilus F. Rodenbough fell into the latter category. In fact, it’s quite likely that only a handful of readers of this blog have ever heard of Rodenbough. He probably would have wanted it that way. Nevertheless, his story has languished in obscurity for more than a century, and the time has come to pay tribute to a brave man who was a fine soldier who sacrificed his health in the service of his country. Instead of allowing that to destroy his life, Rodenbough used his post-Army career to become one of the most gifted and prolific military historians of the Nineteenth Century.

The son of Charles and Emily Rodenbough, Theophilus Francis Rodenbough was born in Easton, Pennsylvania on November 15, 1838. The boy’s father owned a rolling mill and wire factory where the first telegraph wire was made. He had one brother, Joseph K. S. Rodenbough, who was also a successful businessman in Easton after the Civil War. His father was active in the Presbyterian church, and served on a number of boards of trustees, including that of a local bank.

Theophilus, a child of privilege, attended private schools, had special tutors, and enrolled in a course of mathematics and English literature at Easton’s Lafayette College in 1856 and 1857. He left Lafayette after a year of studies and tried his hand at business, a field for which he was not well suited. The young man seemed adrift, searching for his life’s calling. As the storm clouds of war gathered on the horizon in 1860, the young man realized that he might enjoy a soldier’s life, and he set about pursuing his new dream.

Rodenbough enlisted the assistance of Representative Andrew H. Reeder, his Congressman, and began his campaign to obtain an officer’s commission. On March 27, 1861, a scant two weeks before the first shots at Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln signed a second lieutenant’s commission for Rodenbough. Rodenbough would join the 2nd U. S. Dragoons, a legendary unit that produced the likes of John Buford and Wesley Merritt. Not long after the outbreak of the Civil War, the Regular Army’s mounted units were reorganized and the 2nd Dragoons received a new designation, the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Now that he wore a second lieutenant’s shoulder straps, Theo Rodenbough had to learn his chosen trade. Unlike today, where new officers have the benefit of attending Officer Candidate School, there was no such luxury in 1861.

To learn how to be a soldier, Rodenbough reported to the Cavalry School of Practice at the Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. There, he underwent intensive training and learned his new trade. The bright young man quickly demonstrated administrative abilities and became post adjutant and quartermaster for the Cavalry School, serving in that role during the first year of the Civil War. As a reward for his good service, he was promoted to first lieutenant later in 1861. By the time he reached his first anniversary in the United States Army, the young officer had mastered the skills needed to command horse soldiers in the field, and he joined his regiment in time to participate in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

On July 17, 1862, just fifteen months after joining the army, Rodenbough received a second promotion, this time to captain. By way of comparison, John Buford, considered by many to be the finest cavalryman of the American Civil War, did not receive his captain’s bars until he had served in the army for eleven years. Of course, the coming of war provided ample opportunities for a capable officer to advance his career, and Rodenbough benefited by it. Rodenbough served with his regiment throughout 1862, and was captured at the Battle of Second Bull Run on August 30, 1862. He was exchanged a week later and rejoined his regiment just in time for the 1862 Maryland Campaign. In October 1862, he went on recruiting duty, raising a new company of Regulars, Co. L, of which he assumed command.

During the spring of 1863, he led a squadron on the Stoneman Raid in April-May, 1863. He commanded a squadron at the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, where he was slightly wounded and had two horses shot out from under him. On June 28, 1863, Capt. Wesley Merritt, commander of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, received a commission as brigadier general of volunteers and assumed command of the Army of the Potomac’s Reserve Brigade. Rodenbough, the regiment’s senior captain, took command of the 2nd U.S., just two scant years after joining the army. His rise through the ranks of the Regular Army, notorious for slow promotions, was meteoric.

He commanded the 2nd U.S. at Gettysburg and during the retreat, as well as during the fall fighting in 1863. Rodenbough had two more horses shot out from under him during the course of the Gettysburg Campaign. In the spring of 1864, with Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan in command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, the Union horse soldiers expected a busy campaigning season. They were not disappointed. Rodenbough led his regiment at the Battle of Todd’s Tavern on May 7, 1864, at Yellow Tavern on May 11, and during the Richmond Raid of May 1864.

During the opening moments of the Battle of Trevilian Station, on June 11, 1864, Rodenbough received a serious wound when shot at point blank range in the left shoulder by a South Carolina cavalryman. Following Merrit’s instructions, Rodenbough led the advance of the Regulars himself, riding alone and in front of the rest of the Reserve Brigade. As he turned to give orders, a South Carolinian of Brig. Gen. Matthew C. Butler’s Brigade shot him. Rodenbough turned over command of the regiment to his senior captain and retired, desperately wounded.

Merritt praised his subordinate. “Had Rodenbough simply detached the squadron, transmitted the orders through his adjutant and remained with his regiment he would have executed my order in the customary way. As it was I judged his action then as I have since regarded it as especially distinguished and of great benefit, as an example of valor, as well as leading quickly to an important result.” Sheridan urged Rodenbough’s promotion as a result of his valor on June 11. Thirty years later, Merritt submitted Rodenbough’s name for a Medal of Honor, over Rodenbough’s objections, writing, “I know of no living officer more surely entitled to the honor than he.” In 1894, Rodenbough received the Medal of Honor “for distinguished gallantry in action at Trevilian Station while handling his regiment with great skill and unexampled valor.” Rodenbough responded, “I value this distinction especially because it comes to me at the instance of my former commander, Gen. Merritt.”

Rodenbough went on sick leave and recruiting duty before rejoining his regiment in September 1864, just in time for the Third Battle of Winchester. There, in the great mounted charge of five brigades at Fort Collier, on September 19, 1864, with Rodenbough leading his Regulars forward, he received another severe wound, this time costing him his right arm, which was amputated three inches below the shoulder. “At the battle of the Opequon, he displayed almost unparalleled gallantry and coolness,” observed Maj. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert, commander of the Army of the Shenandoah’s Cavalry Corps, “finally, near Winchester while charging at the head of his regiment in a brigade against the enemy’s infantry, he received a wound which cost him his right arm.”

In recognition of his valor at Winchester, he was brevetted major “for gallant and meritorious service.” The severely wounded captain spent three weeks convalescing in the Winchester home of a staunch Unionist before going home to Easton for another three weeks. He then did recruiting duty in Philadelphia from November 1864-April 1865. He received a brevet to lieutenant colonel “for gallant and meritorious conduct during the war” on March 19, 1865.

During the winter of 1864-65, Sheridan and Torbert mounted a campaign to obtain a colonel’s commission for Rodenbough so that he could take over the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry. “He is a gallant and meritorious young officer,” wrote Sheridan, “and would do honor to the grade asked for him.” Torbert echoed a similar note: “He is one of the most deserving young officers of the cavalry, and will not disappoint any trust reposed to him.” With such distinguished support for his promotion, Rodenbough received a commission as colonel of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry on April 29, 1865, and the thrice wounded officer served in the Middle Military Division, commanding the Brigade District of Cumberland, Maryland and the Sub-District of Clarksburg, West Virginia from June until November 1865.

Just four years and four months after joining the army, in July 1865, he received a brevet to brigadier general, U.S. volunteers, “for gallant and distinguished conduct during the war,” and also received an assignment to duty at that rank from President Andrew Johnson. Dated March 13, 1865, he also received a brevet to colonel in the U. S. Army “for gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Todd’s Tavern,” May 7, 1864 and to brigadier general, U. S. Army “for gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Cold Harbor.”

In recommending Rodenbough for his final brevet, Sheridan wrote, “Colonel Rodenbough was one of my most gallant and valuable young officers, under my command, in the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. He was constantly in the field with his regiment, the 2nd U. S. Cavalry (a portion of the time in command of it), from the spring of ’62 up to the time of his being wounded whilst gallantly leading his regiment at the Battle of Opequon, September 19, 1864.”

On October 31, 1865, he mustered out of the volunteer service and returned to 2nd U. S. Cavalry. In the winter of 1865-66, he joined the staff of Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge as Acting Assistant Inspector General, a position he held until May 1866. “An educated soldier of strict integrity and excellent morals, his ability and past services entitle him to promotion,” urged Dodge in a letter to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in 1866. Rodenbough served at various posts in Kansas in 1866, and then received an appointment as major of the 42nd U. S. Infantry on July 28, 1866. He served with the regiment at Hart Island, New York and in various staff positions until May 1867, when he assumed command of the Plattsburgh Barracks in New York until the end of the year.

He then commanded the regiment and post of Madison Barracks in Sackett’s Harbor, New York from December 1867 to April 1869. “On the eve of your departure from this command I avail myself of the opportunity to express my thanks for the efficient manner in which you discharged your duties while serving under me in the Department of the East,” proclaimed Maj. Gen. George G. Meade in the spring of 1869, “both as regimental commander and in charge of the military station at Sackett’s Harbor. Your official course has met my approval, and I feel confident that to whatever position you are assigned you will display the same zeal and efficiency which characterized your conduct here.”

Rodenbough went on recruiting duty in Cincinnati and Detroit for a time. In December 1870, he appeared before a Retiring Board commanded by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. After hearing testimony from surgeons and from Rodenbough himself, the panel concluded that the cavalryman was “incapacitated for active service, and that said incapacity is due to the loss of his right arm, about three inches below the shoulder joint, in consequence of a wound received at the Battle of Winchester, September 19, 1864.” He was retired “with full rank of Colonel of Cavalry, on account of wounds received in the line of duty.” He was just thirty-two years old.

The gallant young colonel had married Elinor Frances Foster at the Church of the Incarnation in New York City on September 1, 1868. Their forty-four year marriage was fruitful, producing two daughters and a son, although their first child, Mary McCullagh Rodenbough only lived two years. After retiring from the Army, he remained active and productive. He served as Deputy Governor of the U. S. Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D. C. in 1870-1871, and the accepted an appointment as General Eastern Agent, Pullman Car Company for two years. He served a two-year term as Associate Editor of the Army and Navy Journal in 1876-77, and became Secretary and Editor of the Journal in 1878, a post he held for twelve years. From 1891-1893, he served as Vice President of the Military Service Institution of the United States, and as Chief of the Bureau of Elections, City of New York, 1890-1892.

The gallant young colonel had married Elinor Frances Foster at the Church of the Incarnation in New York City on September 1, 1868. Their forty-four year marriage was fruitful, producing two daughters and a son, although their first child, Mary McCullagh Rodenbough only lived two years. After retiring from the Army, he remained active and productive. He served as Deputy Governor of the U. S. Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D. C. in 1870-1871, and the accepted an appointment as General Eastern Agent, Pullman Car Company for two years. He served a two-year term as Associate Editor of the Army and Navy Journal in 1876-77, and became Secretary and Editor of the Journal in 1878, a post he held for twelve years. From 1891-1893, he served as Vice President of the Military Service Institution of the United States, and as Chief of the Bureau of Elections, City of New York, 1890-1892.

With the coming of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the sixty-year old warrior tried to obtain a commission and take the field again, writing, “Here is an old sword-blade not so rusty that it will take a respectable polish yet; and I imagine there are several others on the Retired List.” He actively campaigned for an administrative position in the army, but his age and disabilities produced a gentle rebuff. He tried again in 1904, now sixty-four years old, writing, “I have the honor to apply for assignment to duty and detail on recruiting or other service, preferably with station in [New York City].” Rebuffed again, due to an act of Congress, Rodenbough was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, retired, in May 1904, meaning that the honorific of “general” became real, and not just by brevet.

Filling his retirement years, General Rodenbough proved to be a prolific writer and gifted historian. In addition to a comprehensive family genealogy, he wrote numerous articles on diverse topics such as Sheridan’s May 1864 Richmond Raid, the Trevilian Raid, lessons learned by the cavalry in the Civil War, and others. He authored a superb history of his former regiment titled From Everglade to Canon with the Second Dragoons (1875) as well as a history of the Anglo-Russian dispute over Afghanistan (1882). He also wrote The Bravest Five Hundred of 1861, providing thumbnail sketches of various Medal of Honor winners, and a companion volume, Uncle Sam’s Medal of Honor, as well as co-authoring a history of the United States Army. He edited the cavalry volume of Francis Trevelyan Miller’s Photographic History of the Civil War, and headed the committee given the task of preparing a regimental history for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

After a long and productive life, Theophilus F. Rodenbough died at his home in New York City on December 19, 1912. His wife, who joined him in death a few years later, survived him. He was buried with full military honors in the family plot in Easton Cemetery in his hometown. He was seventy-four years old, and he had packed a great deal of living into those years.

After a long and productive life, Theophilus F. Rodenbough died at his home in New York City on December 19, 1912. His wife, who joined him in death a few years later, survived him. He was buried with full military honors in the family plot in Easton Cemetery in his hometown. He was seventy-four years old, and he had packed a great deal of living into those years.

In nine years and eight months in the Regular Army, this dashing horse soldier earned five promotions, two brevets in the volunteer service, and four brevets in the Regular service. Along the way, he impressed almost every officer he served under. “General Rodenbough is a cultivated and refined gentleman of ability and integrity,” wrote Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, summing him up nicely, “and is well and favorably considered wherever known. His record as an officer during the war was irreproachable, and he was disabled for life by the loss of an arm while gallantly performing his duty in battle.”

His rise had been meteoric, and only his battle wounds terminated a promising military career that probably would have led to high command. But for those wounds, Rodenbough likely would be remembered as one of the greatest horse soldiers in American history. Thus ended the fascinating life of a gifted soldier and scholar, a man who spent his life in the service of the Army that he loved, and in doing the duty that marked his character.

Here’s to Theo Rodenbough, forgotten cavalryman, Medal of Honor recipient, and cavalry historian. He was one of those natural soldiers who rose to prominence despite a lack of any formal military training.

Scridb filter Today marks the Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, fought March 17, 1863, along the banks of the Rappahannock River in Culpeper County, Virginia. Please click on the image to see a larger version of this contemporary depiction of the fighting at Kelly’s Ford that St. Patrick’s Day.

Today marks the Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, fought March 17, 1863, along the banks of the Rappahannock River in Culpeper County, Virginia. Please click on the image to see a larger version of this contemporary depiction of the fighting at Kelly’s Ford that St. Patrick’s Day.

That day, Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell’s Second Cavalry Division of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac forced its way across the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and brought the Confederate cavalry brigade of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to battle. The fight lasted for most of the day. First, Averell’s men had to force a crossing of the river, pushing through Confederate rifle pits. They then had to force their way through felled trees that blocked the road. Once they Union horse soldiers forced their way across the river and through the abatis, Averell then ordered his men to charge. Mounted charges met by mounted countercharges by Fitz Lee’s horsemen went back and forth for much of the afternoon. Maj. John Pelham, Jeb Stuart’s gifted chief of horse artillery, foolishly joined a charge by the 5th Virginia Cavalry near the Wheatley farm, and received a mortal wound when a Union artillery shell burst on a stone wall, spraying deadly shrapnel. One of those pieces of shrapnel took Pelham’s life.

Daniel Davis has written a nice account of the battle that appears over at Emerging Civil War. I recommend it to you.

Averell pushed the Confederate horsemen back a mile or two, and then he paused to dress his lines. The final charges too place on the property just preserved by the Civil War Trust. Incorrectly believing that the Confederate cavalry had received infantry reinforcements, and with his force alone and behind enemy lines, Averell broke off and withdrew from the battlefield, leaving it in Fitz Lee’s hands. By all measures, Kelly’s Ford was a Confederate victory. Lee’s troopers held the battlefield at the end of the day, and Averell failed to accomplish his strategic goal, which was to disperse the Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County. However, that victory cost the Confederacy the services of John Pelham.

Averell pushed the Confederate horsemen back a mile or two, and then he paused to dress his lines. The final charges too place on the property just preserved by the Civil War Trust. Incorrectly believing that the Confederate cavalry had received infantry reinforcements, and with his force alone and behind enemy lines, Averell broke off and withdrew from the battlefield, leaving it in Fitz Lee’s hands. By all measures, Kelly’s Ford was a Confederate victory. Lee’s troopers held the battlefield at the end of the day, and Averell failed to accomplish his strategic goal, which was to disperse the Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County. However, that victory cost the Confederacy the services of John Pelham.

For a larger version of Steve Stanley’s excellent battle map (which shows the recently preserved battlefield land in yellow), please click on the map. As always, I am grateful to the Civil War Trust for allowing me to borrow its extremely useful interpretive maps.

My friend Craig Swain has a post on his blog today about the commemoration of the battle that took place today, including some photos of the battlefield as it appears today. It includes photos of the new pullover and new interpretive markers that have just been placed on the land preserved by the Civil War Trust. Please check them out.

There are some interesting quotes by participants in the Battle of Kelly’s Ford that provide insight into the fierce fighting there. “A cavalry charge is a terrible thing. Almost before you can think, the shock of horse against horse, the clash of steel against steel, crack of pistols, yells of some poor lost one, as he lost his seat and went down under those iron shod hoofs that knew no mercy, or the shriek of some horse overturned and cut to pieces by his own kind,” recalled Pvt. William Henry Ware of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry. “It is Hell while it lasts, but when man meets his fellow man, face to face, foot to foot, knee to knee, and looks him in the eye, the rich red blood flows through his veins like liquid lightning. There is blood in his eye, Hell in his heart, and he is a different man from what he is in the time of peace.” One of Averell’s men left a parallel description. “It was like the coming together of two mighty railroad trains at full speed. The yelling of men, the clashing of sabers, a few empty saddles, a few wounded and dying, and the charge is over. One side or the other is victorious, perhaps, only for a few minutes, and then the contest is renewed,” observed Sgt. George Reeve of the 6th Ohio Cavalry. “A charge of this kind is over almost before one has time to think of the danger he is in.”

Moreover, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford proved to be a real turning point in the evolution of the Union cavalry. For the first time, the Federal horsemen stood and fought the very best that the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Division had to offer, and the Federals gave as good as they got. Lt. Joseph A. Chedell of the 1st Rhode Island, wrote that Kelly’s Ford was the “first real, and perhaps the most brilliant, cavalry fight of the whole war.” From that moment forward, the Union horsemen believed that they were the equals of Stuart’s vaunted troopers, and from that moment forward, the blueclad horse soldiers went into battle with confidence and skill. Just three months later, those same troopers–no longer commanded by Averell–fought Stuart’s troopers to a standstill on nearby Fleetwood Hill during the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station.

That evolution–and its implications for the rest of the Civil War in the east–make this day of brutal combat worth commemorating. Today, we pay tribute to the brave men of both sides who crossed sabers during the Battle of Kelly’s Ford.

Scridb filter Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

We’ve long known that Carpenter–a very intelligent and literate man–left behind a large set of some of the best Civil War letters home to be found anywhere. They are located in his home town of Philadelphia at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The problem is that they are in bound volumes and HSP will not permit them to be photocopied. So, if a researcher wants to use them, they must be transcribed by hand, which is, to say the least, a great inconvenience. That’s why the letters have never been published as a set, even though they really deserve to be. He also published a number of good articles on cavalry service and a large family genealogy (Carpenter was directly descended from Samuel Carpenter, who was William Penn’s right-hand man, meaning he was a Philadelphia blue-blood). His brother, J. Edward Carpenter, served as a major in the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry–a Philadelphia regiment–and left behind one of the best contemporary accounts of what we now know as “Keenan’s Charge” on May 2, 1863 during the Battle of Chancellorsville. Both Carpenter brothers were good and prolific writers.

What we didn’t know is that the letters at HSP are only part of the collection of material he left behind. There are also diaries and a sketchbook of Carpenter’s observations during his time in the field during the Civil War. Bud Hall recently purchased this collection and found some amazing things therein. The most amazing find–and perhaps the most valuable of the images–is a sketch Carpenter drew in December 1863 of St. James Church–which sits in the middle of the Brandy Station battlefield, and was the site of the charges of the 6th Pennsylvania and 6th U.S. Cavalry during the morning phase of the the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. Carpenter drew the sketch just before the troopers of the 6th U.S. tore the church down to use the wood and pews for firewood and the bricks to build chimneys for their huts during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. This is the ONLY known contemporary image of the church, and it finally answers a question that those of us who study the Battle of Brandy Station have long wondered: What did St. James Church look like? Bud spent 25 years searching for a contemporary image of the little church and could never locate one. A 1989 archaeological survey of the church site told us what the footprint of the church looked like, and Bud speculated what it looked like, but nobody knew for sure. Thanks to Carpenter, we finally know the answer.

Below is a profile of St. James Church written by Bud Hall that gives the history of this otherwise obscure little church in the woods:

The Little Church that Would Not Die–St. James Episcopal: Rebirth of a Country Church

Richard Hoope Cunningham and his wife Virginia (Heth) arrived in Culpeper in 1833 and built a magnificent home, “Elkwood,” fronting the Rappahannock. Devout Christians, the Cunninghams routinely forded the river and attended services in Fauquier.

Weary of traversing a waterway that often proved dangerously swollen, the Cunninghams selected two acres about two miles back from the river as a suitable church site. Along with their neighbors, the Cunninghams then endowed the construction of a “first class country church.”

The two-story church—made of red brick fired on-site by slave labor—stood 40 by 40 feet, was “carpeted and nicely furnished, with cushioned pews.” Church officials were especially proud of its “big gallery all around for the colored people.” The total cost of construction materials was about $2000.

The beloved Rev. John Cole served as the first Rector of the new church in 1840, later consecrated in 1842 as St. James Episcopal Church. By 1860, the congregation boasted 28 communicants, with 40-50 black and white souls attending weekly services. A cemetery was laid out and all races were interred therein, with the same lovely periwinkle covering all beneath.

The little church proved so prosperous a parsonage loomed, and St James’s members donated $3000 to that end in 1861. But as events transpired, this munificent outlay soon reverted back as member families needed those funds for the next four years. War had come to Culpeper, and almost all of the county’s cherished churches were tallied as casualties during the ruinous conflict. And St. James was the first Culpeper house of worship to experience defilement, and then finally, total destruction.

Located near the wartime intersection of three roadways—Beverly’s Ford Road; Winchester Turnpike and Green’s Mill Road—St. James’s strategic placement near the river guaranteed the modest structure would suffer an inevitable concussive impact centered as it was between contending armies.

And by the thousands, Blue and Gray combatants tramped and fought about St. James. In 1862, pews were removed to enfold Rebel dead incurred in a fierce artillery duel. On June 9, 1863, fighting raged in front of St. James as Jeb Stuart’s legions beat back Federal charges during the Battle of Brandy Station. Several Rebel soldiers killed nearby sleep their final rest today in St. James’s burial ground.

Two Union soldiers in late 1863 left insightful glimpses of St. James: The first, an Illinois trooper, gazed upon the church and wrote his Chicago parents, “I admire the taste of Virginians in regard to building churches. They are not imposing structures and are always located in the woods.” A Pennsylvania officer described St. James as a “modest sanctuary…suggesting a time back when the woods were the first churches.”

Ironically, this latter soldier participated in taking St. James apart brick by brick in December 1863 to be used as chimney material during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac. Soon there was nothing left. Even the church bible was stolen. Robbed of their precious church, St. James members “worshipped God, like the primitive Christians, in private homes.”

But all wars finally do end, and in 1865, a new church was sought to replace St. James. We don’t know why the former site of St. James was not utilized; perhaps the reasoning suggested nothing more than the fact Brandy Station offered convenience for a post-war congregation. And then again maybe the bitterness over the loss of their lamented country church precluded a return to the “crime scene.”

“St James Church has risen from the ashes in the embodiment of Christ Episcopal Church at Brandy Station,” an exultant Rev. John Cole proclaimed in 1868.

In 1869, the new church was dedicated and consecrated “to supply the place of the building…entirely destroyed during the recent war.” Still offended at the wanton destruction of St James, Christ Church petitioned the Federal government for compensatory redress, and in 1914 the U.S. Court of Claims allowed the sum of $1,575 expended “as an equitable claim …that the United States received the benefit of the use of the material claimed for.”

Having fulfilled its duty by satisfying the honor of its ancestor church, the esteemed Christ Church congregation now also has St. James’s bible back in the fold—graciously returned by a former enemy. Christ Church continues today to hold in trust for the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia the St. James Church parcel, and the Brandy Station Foundation deferentially maintains, under lease, this beautiful, sacred church ground and its lonely cemetery.

Enter St. James today, if you will, and quietly and reverently experience the holy memory of a little church in the woods that refused to die.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

The image is very accurate: the graves are correctly shown, as is a defensive trench just beneath the gravestones, and if you visit the site today, you can still find the same small grouping of graves nestled among a grove of trees grown up since the war.

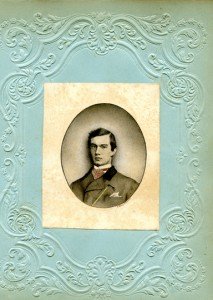

The self-portrait of Carpenter at the top of this post also comes from the sketchbook acquired by Bud. The same rules apply to it. I had looked for an image of him for years, but could only find one from late in his career, so I am very pleased to finally see a wartime image of him. You can see a larger image of it by clicking on it, too.

Bud has very generously agreed to permit me to use any of these images, and any of the other material that he now owns, in a future volume on Carpenter. I haven’t quite decided whether to edit the letters or to write a full-length biography of this fascinating soldier, but I will do something with them that makes good use of Bud’s collection of outstanding primary source material from Carpenter himself.

I’m tickled to be able to offer you the first look at these materials. Thanks to Bud Hall for permitting me to do so.

Scridb filterFor those interested in the upcoming Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford (fought on March 17, 1863), my friend and fellow BSF board member in exile Craig Swain is leading a commemoration of the battle next Sunday (St. Patrick’s Day), from 2:00-3:15. The commemoration will occur on the battlefield proper, at the time when the battle was taking place. The event is to both commemorate the battle, but also to dedicate a new interpretive spot on some of the ground preserved last year by the Civil War Trust.

Craig has further details on his blog. If you’re in the area, please check out this event!

Scridb filterTed Savas has a gift for getting his company’s books placed with the History Book Club, the Military Book Club, and Book of the Month Club 2. He has a terrific record of success with doing so; of my works, The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Final Campaign, and the second edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions: Farnsworth’s Charge, South Cavalry Field, and the Battle of Fairfield, July 3, 1863 were both featured selections.

Ted just informed me that the new edition of Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg: The Battles for Brinkerhoff’s Ridge and East Cavalry Field, July 2 – 3, 1863 has also been chosen by the book clubs. Ted informs me that it will be a featured alternate in the July 2013 catalog offering, which mails on June 2, 2013. I am, of course, very flattered to learn this, and am excited to be featured by the book clubs once more. For those of you who are members of any of the three book clubs, please keep an eye out for it.

Thanks again to Ted for making this happen.

Scridb filterThanks to Bruce Long for bringing his blog on the Civil War in northeast North Carolina to my attention, as I had missed it previously. Those of you who have followed this blog for a long time know of my fascination with the Civil War in the Tarheel State, which has long interested me a great deal. I’m glad to add this one to the blogroll.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like