Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

We’ve long known that Carpenter–a very intelligent and literate man–left behind a large set of some of the best Civil War letters home to be found anywhere. They are located in his home town of Philadelphia at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The problem is that they are in bound volumes and HSP will not permit them to be photocopied. So, if a researcher wants to use them, they must be transcribed by hand, which is, to say the least, a great inconvenience. That’s why the letters have never been published as a set, even though they really deserve to be. He also published a number of good articles on cavalry service and a large family genealogy (Carpenter was directly descended from Samuel Carpenter, who was William Penn’s right-hand man, meaning he was a Philadelphia blue-blood). His brother, J. Edward Carpenter, served as a major in the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry–a Philadelphia regiment–and left behind one of the best contemporary accounts of what we now know as “Keenan’s Charge” on May 2, 1863 during the Battle of Chancellorsville. Both Carpenter brothers were good and prolific writers.

What we didn’t know is that the letters at HSP are only part of the collection of material he left behind. There are also diaries and a sketchbook of Carpenter’s observations during his time in the field during the Civil War. Bud Hall recently purchased this collection and found some amazing things therein. The most amazing find–and perhaps the most valuable of the images–is a sketch Carpenter drew in December 1863 of St. James Church–which sits in the middle of the Brandy Station battlefield, and was the site of the charges of the 6th Pennsylvania and 6th U.S. Cavalry during the morning phase of the the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. Carpenter drew the sketch just before the troopers of the 6th U.S. tore the church down to use the wood and pews for firewood and the bricks to build chimneys for their huts during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. This is the ONLY known contemporary image of the church, and it finally answers a question that those of us who study the Battle of Brandy Station have long wondered: What did St. James Church look like? Bud spent 25 years searching for a contemporary image of the little church and could never locate one. A 1989 archaeological survey of the church site told us what the footprint of the church looked like, and Bud speculated what it looked like, but nobody knew for sure. Thanks to Carpenter, we finally know the answer.

Below is a profile of St. James Church written by Bud Hall that gives the history of this otherwise obscure little church in the woods:

The Little Church that Would Not Die–St. James Episcopal: Rebirth of a Country Church

Richard Hoope Cunningham and his wife Virginia (Heth) arrived in Culpeper in 1833 and built a magnificent home, “Elkwood,” fronting the Rappahannock. Devout Christians, the Cunninghams routinely forded the river and attended services in Fauquier.

Weary of traversing a waterway that often proved dangerously swollen, the Cunninghams selected two acres about two miles back from the river as a suitable church site. Along with their neighbors, the Cunninghams then endowed the construction of a “first class country church.”

The two-story church—made of red brick fired on-site by slave labor—stood 40 by 40 feet, was “carpeted and nicely furnished, with cushioned pews.” Church officials were especially proud of its “big gallery all around for the colored people.” The total cost of construction materials was about $2000.

The beloved Rev. John Cole served as the first Rector of the new church in 1840, later consecrated in 1842 as St. James Episcopal Church. By 1860, the congregation boasted 28 communicants, with 40-50 black and white souls attending weekly services. A cemetery was laid out and all races were interred therein, with the same lovely periwinkle covering all beneath.

The little church proved so prosperous a parsonage loomed, and St James’s members donated $3000 to that end in 1861. But as events transpired, this munificent outlay soon reverted back as member families needed those funds for the next four years. War had come to Culpeper, and almost all of the county’s cherished churches were tallied as casualties during the ruinous conflict. And St. James was the first Culpeper house of worship to experience defilement, and then finally, total destruction.

Located near the wartime intersection of three roadways—Beverly’s Ford Road; Winchester Turnpike and Green’s Mill Road—St. James’s strategic placement near the river guaranteed the modest structure would suffer an inevitable concussive impact centered as it was between contending armies.

And by the thousands, Blue and Gray combatants tramped and fought about St. James. In 1862, pews were removed to enfold Rebel dead incurred in a fierce artillery duel. On June 9, 1863, fighting raged in front of St. James as Jeb Stuart’s legions beat back Federal charges during the Battle of Brandy Station. Several Rebel soldiers killed nearby sleep their final rest today in St. James’s burial ground.

Two Union soldiers in late 1863 left insightful glimpses of St. James: The first, an Illinois trooper, gazed upon the church and wrote his Chicago parents, “I admire the taste of Virginians in regard to building churches. They are not imposing structures and are always located in the woods.” A Pennsylvania officer described St. James as a “modest sanctuary…suggesting a time back when the woods were the first churches.”

Ironically, this latter soldier participated in taking St. James apart brick by brick in December 1863 to be used as chimney material during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac. Soon there was nothing left. Even the church bible was stolen. Robbed of their precious church, St. James members “worshipped God, like the primitive Christians, in private homes.”

But all wars finally do end, and in 1865, a new church was sought to replace St. James. We don’t know why the former site of St. James was not utilized; perhaps the reasoning suggested nothing more than the fact Brandy Station offered convenience for a post-war congregation. And then again maybe the bitterness over the loss of their lamented country church precluded a return to the “crime scene.”

“St James Church has risen from the ashes in the embodiment of Christ Episcopal Church at Brandy Station,” an exultant Rev. John Cole proclaimed in 1868.

In 1869, the new church was dedicated and consecrated “to supply the place of the building…entirely destroyed during the recent war.” Still offended at the wanton destruction of St James, Christ Church petitioned the Federal government for compensatory redress, and in 1914 the U.S. Court of Claims allowed the sum of $1,575 expended “as an equitable claim …that the United States received the benefit of the use of the material claimed for.”

Having fulfilled its duty by satisfying the honor of its ancestor church, the esteemed Christ Church congregation now also has St. James’s bible back in the fold—graciously returned by a former enemy. Christ Church continues today to hold in trust for the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia the St. James Church parcel, and the Brandy Station Foundation deferentially maintains, under lease, this beautiful, sacred church ground and its lonely cemetery.

Enter St. James today, if you will, and quietly and reverently experience the holy memory of a little church in the woods that refused to die.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

The image is very accurate: the graves are correctly shown, as is a defensive trench just beneath the gravestones, and if you visit the site today, you can still find the same small grouping of graves nestled among a grove of trees grown up since the war.

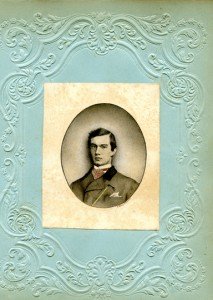

The self-portrait of Carpenter at the top of this post also comes from the sketchbook acquired by Bud. The same rules apply to it. I had looked for an image of him for years, but could only find one from late in his career, so I am very pleased to finally see a wartime image of him. You can see a larger image of it by clicking on it, too.

Bud has very generously agreed to permit me to use any of these images, and any of the other material that he now owns, in a future volume on Carpenter. I haven’t quite decided whether to edit the letters or to write a full-length biography of this fascinating soldier, but I will do something with them that makes good use of Bud’s collection of outstanding primary source material from Carpenter himself.

I’m tickled to be able to offer you the first look at these materials. Thanks to Bud Hall for permitting me to do so.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Eric, thanks for the quality attention given to this interesting topic. And I imagine your worthy readers will find themselves equally fascinated by the history of a “little church in the woods” that refused to die..

And for those of us who have been involved from the beginning (1987) with the preservation of the Brandy Station Battlefield, you should know that St. James holds a special place in our hearts simply because the vital archeology/history study of this site in 1989 conclusively demonstrated to the developer and his political supporters that Brandy Station was in fact a great battlefield where men once fought and died in great numbers.

I would urge that those interested in this central preservation revelation seek out a copy of “The History and Archeology of Saint James Episcopal Church, Brandy Station, Virginia.” I am informed it is available on Amazon.

Brandy Station is today a beautiful, pristine cavalry battlefield and the story of St. James epitomizes to me the reality that we preservationists just don’t hold up the white feather because somebody shows up with plans (or bulldozers) to develop our sacred battlefields. No, we fight them openly, and when we marshal our collective forces with “salvation” in mind, we most always win.. May it always be so..

In this large, vibrant Civil War preservation and scholarship community, we each all owe our friends a deep debt of gratitude for bringing things to our attention that they know are important to us.. And in this regard, I wish to convey my gratitude to the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry’s dutiful champion, Andrew German, Mystic, CT, who alerted me to the St. James image–which was bought with 15 minutes of Andy telling me about it. My wife Deborah Fitts and Andy were good buddies, and now I am proud and grateful he remains my dear friend.

Thanks, Eric, for all you do, for all of us who care about Brandy Station.

-Su amigo.. Bud

Clark B. Hall

Very, very interesting. I enjoyed it immensely,

This is great, absolutely fascinating.

Ironically, I just picked up the 6th’s unit history from 1900 ‘From Yorktown to Santiago: with the Sixth U. S. Cavalry’

by William H. Carter.

Chris

Fantastic!

Congratulations on this find. On my many visits to the battlefield I’ve wondered what the 6th PA Cavalry saw in front of them during their charge across the field. Looking forward to Bud’s book!

Wow ! That is awesome. Sometimes I view this blog and am simply amazed at the information that you are able to provide, Eric.

Thanks, everyone. You’re all very kind.

It’s quite an exciting find. Those of us who care about this battle are just tickled that this image has surfaced.

By finding this elusive sketch Bud Hall has ‘rescued’ yet another piece of the Brandy Station Battlefield and has allowed us once again to see St. James Church back in its historic form.

I have been amazed at how many churches figured so prominently in the battles of the Civil War. Sudley Church, Shiloh Church, St. James Church, Bethesda Church; all of these and many more saw men fight and die in their church yards. Most of them, like many soldiers who fought around them, didn’t survive the war. Some were rebuilt, some just left as ghosts beckoning us to remember them and the soldiers who fought there.

St. James, which figured very prominently in the Battle of Brandy Station, was ‘lost’ like so many soldiers who fought around it. Indeed who were buried under its very shadow. For decades the church and the battlefield beckoned for remembrance. “We are here”, they beckoned, “don’t forget us, remember what happened”.

Bud Hall heard that call when others didn’t. He saw the church on the knoll, he saw the soldiers fighting in front of it. He remembered and fought to make sure we could remember too.

We are now close to the saving of Fleetwood Hill and the church is now revealed to us. Like the Battle that was fought in her front yard, St. James is unknown no more.

Thanks Bud!

What an exciting find! I’ve been following the posts about Brandy Station with much interest. I look forward to reading and learning more about the preservation progress. You, Mr. Hall, and the others involved, are owed a debt of gratitude for your hard work and diligence.

I really don’t have words to thank Mr. Hall for everything he has done to preserve the memory and heritage of this church. My husband and son cherish the small part they played in recording it’s history.

I am completing a book on Company H, Tenth Cavalry which Louis Henry Carpenter commanded for the first 15 years of its existence. I would like to include his self portrait and perhaps other sketches. I would really appreciate it if you could put me in contact with the person who owns this material so I can ask permission.

Thanks,

Jim Matthews

jjmatthews2@att.net