Category:

Union Cavalry

Interesting coverage of cavalry actions during the Tullahoma Campaign

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

The following article, by a correspondent embedded with the Army of the Cumberland’s Cavalry Corps, appeared on page four of the July 8, 1863 issue of The New York Herald. The entire issue is fascinating, as it covers the fall of Vicksburg, the retreat from Gettysburg, and Tullahoma. Nearly all of page four is devoted to the Tullahoma Campaign, which is often overlooked as compared to the other two campaigns.

MR. E.D. WESTFALL’S DESPATCHES

Headquarters, Reserve Corps

Army of the Cumberland

Shelbyville, Tenn., June 28, 1863

CAVALRY OPERATIONS

The corps of reliable gentlemen have been under a cloud since the movement of the army commenced, left Tuesday. I dislike to acknowledge that all my efforts to enlighten Herald readers in regard to movements on the right have proved futile, but they have this far. A special order denies us the use of the telegraph, and minute hairsplitting about “passes” prevents employment of messengers. However, things have assumed such shape today that I venture to tell how Stanley’s cavalry–temporarily under Gordon Granger’s command–came into possession of this stiff little Union burg. God prosper, henceforward, every loyal man in it. They have suffered enough.

OUR START AND PROGRESS

The “reserve corps,” with General R. B. Mitchell’s cavalry division, moved from Triune on Tuesday morning; the infantry eastward, on the old Murfreesboro road, the cavalry southward, on the Eaglesville pike, directly through the enemy’s country. The infantry, General A. Baird’s division, reached Salem, four miles from Murfreesboro, in good order, without molestation.

THE CAVALRY ADVANCE GUARD,

consisting of the Second Michigan and Ninth Pennsylvania regiments, came upon the rebel pickets just outside the little hamlet called Middleton, eleven miles from Triune. The rebels showed a force about equal to ours, and evinced a desire to obstruct our further advance. They were driven slowly along the execrable road, through the village, till they reached a dense woods beyond it, when they made a desperate stand, opening on our advance with two pieces of artillery. They held the woods and a ploughed field in front of it for an hour, shouting savagely and firing extremely wild.

THE FIGHT.

General Mitchell, impatient at the delay–for night was near at hand–ordered the Second and Ninth to dismount and charge across the field. The passage over the moist, ploughed ground, in the face of the enemy’s fire, was extremely difficult for dismounted men. But these two regiments had an excellent reputation to sustain, and they made the trip, reserving their fire till they approached within thirty yards of the rebel line, then delivering it with precision and rapidity. The graybacks could not stand it, and broke and fled most frantically, leaving eight dead men and sixty or seventy dead horses, but carrying off their wounded and the two guns. The enemy proved to be Brigadier General Martin’s command—part of Wheeler’s cavalry force. 0ur loss was two killed and six wounded. The cavalry camped near the field that night. Three log houses in the village—nearly half its complement of tenement–were accidentally burned during the melee by Tennessee cavalry of Mitchell’s command, who knew them to be the property of violent rebels.

ANOTHER SKIRMISH.

Next day, after another skirmish at Fosterville in which the rebels were again discomfited, the cavalry reached Christiana, on the Shelbyville pike, eight miles and a half from Murfreesboro, where they found Colonel Minty’s and Ed. McCook’s brigades of General Stanley’s cavalry, commanded by General Stanley in person. Infantry and artillery having come over from Triune via Salem in the meantime, quite an imposing force encamped at Christiana in the pouring rain on Wednesday night, and were ready for the offensive in any direction when the day came. Here, I learned that the Twentieth army corps (McCook’s) had passed down the pike in the direction of Shelbyville on Tuesday, and all day long General Granger waited for orders and listened to the sound of McCook’s cannon in the front, six miles away. The rain and the mud were fearful.

EXCITING RUMORS

were afloat that Sheridan’s division of McCook’s corps had met the rebels, and had been driven back in disastrous rout; that a vast force of enemies were approaching the reserve corps on the Shelbyville road; but Gen. Granger was unable to get hold of any positive information respecting either of the exciting topics. So isolated was the reserve that two days passed before we knew exactly where to find Rosecrans’ headquarters. During Thursday and Friday there was considerable skirmishing between pickets of the opposing parties, and our infantry were several times drawn up in line of battle, to await and repel an attack.

SATURDAY MORNING.

Twenty regiments of Stanley’s cavalry moved toward Shelbyville from Christiana, Generals Granger, Stanley and Mitchell at the head of a column of fours which stretched along the pike a distance of four miles. It was a splendid show of strength, and calculated to terrify any force we expected to meet. Four miles in front of Christiana, the cavalry came upon the pickets of the rebel force stationed al Guy’s Gap, and skirmishing began. The rebels were driven luck till we discovered their line of battle formed across the pike at the entrance of the gap.

GUY’S GAP

is naturally a very strong position, and we expected to find it fortified extensively and to meet with a stubborn resistance. The cavalry was deployed to the right and left, and the bugles of the twenty regiments sounded the advance. Ten minutes were sufficient to give us possession of the gap, from which we could see the rebels fleeing along the straight pike toward Shelbyville in the utmost confusion. While the force directly in front were engaged seizing the gap, the regiments on the right were engaged with a strong column of rebels which had been unearthed in that quarter. This column, we afterward learned, was the command of Colonel Cruse, Forrest’s right bower, who was marching from the vicinity or Eaglesville and Triune, across the country, to join General Wharton’s cavalry, near Hoover’s Gap. The presence of Colonel Cruse on our right was unknown to the rebels who held the Gap in front, and his meeting with our cavalry so near Shelbyville was unexpected. He retired with the loss of three men, made a detour toward Shelbyville, and attempted to cross the pike again. Here he met the advance of the Union column, in full pursuit of the rebels from the gap, and his passage was again blocked. This time he gave it up for a bad job and retreated towards Middleton, whence he had come. Since we have heard from Cruse in the vicinity of Triune, and presume he is endeavoring to reach Wharton by way of Columbia.

FORREST DANGEROUSLY WOUNDED.

From a prisoner I learn that Forrest is unable to fight just now, being in a dangerous condition from a wound received in the Spring Hill live fracas. I am convinced that up to the time we appeared in front of Guy’s Gap the rebels knew nothing of our advance in form. I am convinced, also, that had been blessed with sunshine instead of pouring rain all the while, General Rosecrans’ plans for the destruction of Bragg’s army would have succeeded before now.

PURSUIT OF THE REBELS—THEIR WORKS.

The rebel troops who made the stand at Guy’s Gap (Martin’s brigade, of Wheeler’s command) were hotly pursued five miles further down the pike, to the outer line of fortifications around Shelbyville, four miles from the town. Those outer works consisted of a line of rifle pits with flanking batteries, extending from Duck river on the left to Hog mountain on the right–a distance of eight miles. They had been built regardless of expense, and their completeness, location and finish showed them to be the work of a skillful engineer. Reaching this line of works, the rebels paused in their mad flight und made hasty preparation for another stand. A twelve-pounder

cannon, belonging to Wiggins’ rebel battery, was placed in position to rake the pike. The Seventh Alabama Cavalry supported the piece, and opened fire on the head of the Union column as it appeared before the works.

THE CHARGE

was sounded, the Union cavalry rode further up the pike, clamored over the earthworks, sabered such misguided beings as showed a belligerent disposition, and the line of rifle pits was ours. The rebels succeeded in getting away with their guns, but 459 privates, with all the officers of the Seventh Alabama cavalry, were temporarily lost lo the rebel service, prisoners of war. Three brigades of Infantry and two regiments of cavalry, a portion of General Leonidas Polk’s command, had evacuated the position five hours before, and retreated through Shelbyville toward Tullahoma.

THE CHASE WAS KEPT UP.

The Fourth United States cavalry and Seventh Pennsylvania in the advance were close upon the heels of the rebels as they entered Shelbyville. The chase for the last four miles was of the most exciting character. Houses along the road were filled with Union people, who came to the roadside fences, shouted, clapped their hands, hooted at the pale and panting rebels, and cheered the pursuers on. Here and there a jaded rebel horse would drop, with the blood gushing from its mouth and pouring from its wounded sides; the next instant ferocious blue jackets would be upon its terrified rebel rider, with keen sabre in hand, demanding unconditional surrender or swift death. Rebel canteens, haversacks, broken muskets, clothing and corn meal were strewn along the pike throughout the whole distance, from the earthworks to

the town, and dead bodies were numerous.

SHELBYVILLE—THE FIGHT.

It was half past six o’clock when the Unionists reached the town. Four pieces of Wiggins’ rebel battery were planted in the public square, facing towards Murfreesboro, and rebel cavalrymen were flying to and fro in wild confusion. General Wheeler himself was in command. The force, we afterwards learned, was five regiments of cavalry with the four pieces of cannon above mentioned. The cannon in the square opened on our brave fellows, and Wheeler rode about like a madman, trying to get his rebels in shape to make a fight. General Granger sent Lieutenant Colonel Minty with a flanking force of four regiments to our left, and ordered the Fourth United States cavalry and Seventh Pennsylvania to charge into the square and take those guns at all hazards. The charge was made in the presence of an admiring audience of Shelbyville people, who lined the sidewalks, filled the windows and covered the housetops and porches, regardless of bullets, which were flying through the streets from both directions. It was so fierce and desperate that Wiggins was able to fire but one shot from his cannon before he lost three of them. This single round ball cut down six men and four horses. The fourth piece was dragged out of the square, down past the railroad depot, across the Duck river bridge, and started on the gallop toward Tullahoma.

THE SCENE AT THE BRIDGE

beggars description. Men and horses crowded upon it inextricable confusion, the stream filled with rebels struggling to gain the opposite bank, our exasperated soldiers firing at them in the water; Wheeler frantically calling for volunteers to stay the Union torrent long enough for his escape. The First rebel cavalry answered his call, and made a really gallant stand, checking our advance momentarily, while Wheeler and his body guard dashed into the stream and swam for dear life and liberty. Upwards of fifty rebels were drowned in the passage of this stream, among them Major Reid, Wheeler’s adjutant general, and Major Buford, Forrest’s chief of

staff. Wheeler himself, thanks to the bravery of the First rebel cavalry, escaped. The regiment was destroyed or captured almost wholly to save a little major general. The flanking force of Colonel Minty by a citizen in regard to the location of the Tullahoma pike, and the number of fences they expected to encounter. They did not succeed in cutting off the retreat, and the remnant of the rebel force, who were so warlike in the morning, got off towards Tullahoma dispirited and dismayed.

IN POSSESSION OF SHELBYVILLE.

Thus, Saturday night at eight o’clock, General Granger was in possession of Shelbyville, with eight hundred prisoners, three pieces of cannon, twenty thousand bushels of corn and other stores, besides inflicting upon the rebels a loss nearly three hundred killed and wounded. Our total loss since leaving Christiana amounted to eighteen killed and three wounded. It was cheering to meet so many loyal people as we met in Shelbyville. The town has not been belied. Old people and young people, young men and maidens, waving little copies of the Stars and Stripes, stained and dusty from a year’s concealment in secret places, greeted us with “Thank God, you’ve come at last!” The Union feeling is so universally evinced that I did not wonder longer why the rebels “could not bear the town of New Boston.”

Colonel Brownlow’s First Tennessee cavalry participated in the attack. Many of his men were residents of Shelbyville in peaceful times. It was a sweet morsel to these men to fight rebels in the neighborhood of their former homes. A young Tennessean of BrownIow’s regiment rode up before his father’s door while the fight was going on. He dismounted hurriedly and embraced his aged parents, who hardly recognized him at first. The young warrior exchanged short greetings with them, the gray haired man holding his son’s carbine, the feeble mother grasping the bridle of her son’s horse, while the young man eagerly drank the water his pretty sister brought to him—a very pretty but fleeting picture of the “wanderer’s return.” The tableau was dissolved by the old man thrusting the gun into the soldier’s hand, bidding Charley “go on and get your revenge.” The restless Colonel was full of the spirit of his father. He jumped from his horse, kissed his sweetheart, whom his quick eye had singled out from a throng of excited maidens, mounted, again and joined in the charge. Another of Brownlow’s men—his wife looking on then shot the man who had driven him from Shelbyville in front of his own door. Incidents of this character were plenty.

The town of Shelbyville has been treated much better by the rebels since Buell left than one would expect. They left it last night, threatening to return today and burn it, but I fancy it is safe for the present.

The June 27, 1863 Battle of Shelbyville, addressed in detail here, is one of the most fascinating cavalry battles in the war. Minty’s single brigade, augmented by Col. William Brownlow’s First Middle Tennessee Cavalry, made a saber charge that broke and routed two full division of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps. Wheeler went flying into the Duck River, barely escaping capture. I know of no other similar cavalry charge during the entire course of the Civil War. But it has gotten little attention over the years. I aim to correct that.

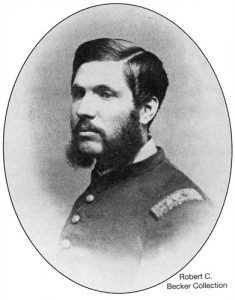

Scridb filterBvt. Brig. Gen. George S. Acker

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Here’s the next in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten cavalrymen of the American Civil War.

George S. Acker was born near Rochester, New York on December 25, 1835. In 1839, his family relocated to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where he lived the rest of his life. “He was a bright and chivalrous young man,” recalled a local resident. He worked in a Kalamazoo hotel before the outbreak of the Civil War, where he was a “popular assistant.”

With the coming of war, he decided to enlist. He helped to recruit a company of the 1st Michigan Cavalry and was commissioned a captain. While serving in the 1st Michigan Cavalry, Acker “took an active part in the contests at Winchester, Orange Court Honse, Cedar Mountain, and the second Bull Run, where, a charge that he led freed Lt. Col. Charles H. Town, who had been captured, and brought him back into the Union lines, badly wounded. He was made Major on September 2, 1862 in recognition of his gallantry.

When the 9th Michigan Cavalry was formed that fall, he was assigned as its lieutenant colonel.The 9th Michigan Cavalry was mustered into service in May 1863. The 9th Michigan, then commanded by Col. James L. David, was ordered to Covington, Kentucky, leaving by detachments, on May 18, 20, and 25, 1863, respectively. Then, on June 4, the regiment marched to Hickman’s Bridge, where on June 12, they were ordered to Mount Sterling, to pursue guerrillas, whom they overtook at Triplett’s Bridge, then completely routed.The regiment then joined the pursuit of Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry, which invaded Indiana and Ohio. Acker “was very prominent in the pursuit and capture of the notorious rebel Gen. John H. Morgan in Ohio in July and August 1863,” noted his obituary, which also said, “He said to his command, ‘Come,’ and led them wherever the enemy opposed or danger threatened.” The 9th Michigan played a significant role at the July 19, 1863 Battle of Buffington Island in southeastern Ohio. In November 1863, Acker was commissioned colonel of the 9th Michigan Cavalry.The Detroit Free Press described Acker’s role in the battle of Morristown, fought on December 10, 1863 as part of the Knoxville Campaign: “Col. Acker threw himself at the head of his regiment and shouted: “Boys, charge the rascals with a yell,’ and himnelf setting the example, with revolver in hand, charged full speed up the hill. The enemy broke ranks and ran in confusion to the rifle-pits, and when the boys saw Col. Acker standing in the rifle-pits sending its contents along the trender, it was enthusiasm run mad that sent his men like a swarm into tbe ditches. It was in vain the rebels tried to stay the storm. After the first charge was fired our boys clubbed their muskets, and thus fought their way through their fortifications.” Acker was wounded in the right leg in combat at Bean’s Station on December 14, 1863 during the Knoxville Campaign. Acker returned to duty in March 1864, in time for the beginning the Atlanta Campaign and commanded his regiment throughout that critical 1864 campaign.

He briefly commanded a brigade during the March to the Sea, and retained command of his regiment for the rest of the war, participating in the battles of the Carolinas Campaign and then in the pursuit of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army to Raleigh, North Carolina. A soldier of the 92nd Illinois remembered him as “a cool and brave cavalry soldier.” He was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers at the end of the war, and mustered out in June 1865. His obituary noted that “His services are often referred to as among the most valuable and gallant of the many excellent officers of Michigan regiments.”

After the Civil War, he led a quiet life, working as a hotelkeeper and milkman. Acker died on September 6, 1879 at the young age of 44. He apparently never married, as his obituary indicates that he was survived by his mother and sister. He was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Union City, Michigan.

Here’s to Bvt. Brig. Gen. George S. Acker, forgotten cavalryman, who did his duty well and honorably throughout the Civil War.

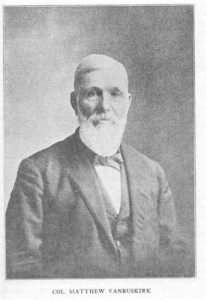

Scridb filterLt. Col. Matthew Van Buskirk

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

It’s been a very long time since my last post, and even longer since my last Forgotten Cavalrymen profile. I’ve been working on the February 11, 1865 Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, which will spur several of these profiles. Here’s the first one, of Lt. Col. Matthew Van Buskirk of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry.

Matthew Van Buskirk was born in Buckmantown, Clinton County, New York, on January 1, 1835. He was the son of Lorenzo Dow Van Buskirk and Louisa Van Buskirk, and had one brother, Albert, born March 20, 1841 (Albert Van Buskirk was killed in action at the Battle of Drury’s Bluff near Petersburg, Virginia on May 16, 1864). After completing his education, the young man relocated to Illinois in 1851, and was still living there with the coming of war in 1861.

He enlisted in the 92nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which was organized at Rockford, Illinois, on September 4, 1862, and was quickly elected captain of Company E. The 92nd Illinois consisted of five companies from Ogle County, three from Stephenson County, and two from Carroll County.The newly formed regiment left Rockford, 11 October 1862, with orders to report to Gen. Horatio G. Wright, in command of the defenses of Cincinnati, Ohio. The regiment was assigned to Gen. Absalom Baird’s Division of the Army of Kentucky. These men soon marched into the interior of Kentucky and was stationed at Mt. Sterling in October to guard against rebel cavalry raids during Braxton Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky. Later, it was assigned to Danville, Kentucky. On January 26, 1863, Baird’s division, including the 92nd Illinois, was transferred to the Army of the Cumberland. The division was assigned to serve in Franklin, Tennessee, and assisted in the pursuit of Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn’s Confederate cavalry raiders. They advanced to Murfreesboro,and occupied Shelbyville, Tennessee on June 27, 1863.

The 92nd Illinois Infantry converted to mounted infantry on July 22, 1863 and was rearmed with Spencer repeating rifles. It was then assigned to join Brigadier General John T. Wilder’s Lightning Brigade for the rest of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’ command of the Army of the Cumberland. During the early phases of what became the Chickamauga Campaign, with the Lightning Brigade leading Rosecrans’ advance, the 92nd Illinois crossed the mountains at Dechard, Tennessee, and took part in the movements opposite and above Chattanooga. The 92nd Illinois then crossed back over the mountains and joined Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas at Trenton, Alabama. On the morning of September 9, the Lightning Brigade led the Union advance to Chattanooga, helping to drive the Confederates from Point Lookout. The 92nd Illinois then entered Chattanooga, unfolding the Union banner on the Crutchfield House. They then pursued the retreating Confederates. Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry attacked the Lightning Brigade near Ringgold, Georgia, inflicting significant casualties on the Federals. At Chickamauga, the 92nd Illinois supported Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds’ Division of Thomas’ 14th Corps.

In April, 1864, the 92nd was doing picket duty at Ringgold, Georgia. On May 7, 1864, the 92nd Illinois, which had now been converted to light cavalry and armed with cavalry weapons, began Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign as part of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s Third Cavalry Division. The 92nd Illinois participated in the Battle of Resaca, Kilpatrick’s failed raid around Atlanta, as well as the Battles of Bethesda, Fleet River Bridge, and Jonesboro, where the regiment lost one-fifth of the men engaged. The regiment moved from Mount Gilead Church, west of Atlanta, on October 1, and took an active part in the operations against Hood’s army, including taking heavy losses at Powder Springs. About this time, Van Buskirk was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 92nd Illinois after Col. Smith D. Atkins was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers and assumed command of a Federal cavalry brigade.

The 92nd Illinois then participated in the various engagements and skirmishes in Sherman’s March to the Sea and then through the Carolinas Campaign of 1865. During its term of service, the 92nd Illinois participated in some forty battles and skirmishes. The regiment was mustered out at Concord, North Carolina, on June 21, 1865, and was then discharged at Chicago, Illinois, on July 10, 1865.

Van Buskirk “was popular with his soldiers and trusted by his superior officers,” noted one biographer. With the end of the war, he settled in Iowa Falls, Iowa, where he successfully operated a store selling boots, shoes and crockery and later dry goods and other items, growing his business into a general merchandising business. Later, he became a gentleman farmer. He married Nellie C. McGiven in 1866, and they had seven children together. Van Buskirk died on January 10, 1901 and was buried in Iowa City’s Union Cemetery. “He was a clear-brained, noble-minded man of action and his life record is worthy of emulation by the youth of this locality whose careers are yet matters for the future to determine,” declared his biographer.Here’s to forgotten cavalryman Matthew Van Buskirk, who performed his duty capably and with honor throughout the American Civil War.

Scridb filterA fictional account of the Battle of Chancellorsville

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

It’s an open question as to who was the worst, biggest, most pathological liar: Alfred Pleasonton or Phil Sheridan. Both were incapable of telling the truth, and both were known for prevaricating in the interest of self-promotion. As I have described him here previously, Pleasonton was a lead from the rear kind of a guy who was a masterful schemer and political intriguer. Pleasonton was the sort of guy who would start a fight on the playground and then step back and watch the chaos that he had started. And he was known for telling whoppers in the hope of promoting himself and his moribund career; his persistent lying and scheming ultimately cost him his command with the Army of the Potomac and found him banished to the hinterlands of Missouri, where, shockingly, he actually did quite well in running down the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price in the fall of 1864. He carried the mocking nickname of “The Knight of Romance” for good reason.

It’s an open question as to who was the worst, biggest, most pathological liar: Alfred Pleasonton or Phil Sheridan. Both were incapable of telling the truth, and both were known for prevaricating in the interest of self-promotion. As I have described him here previously, Pleasonton was a lead from the rear kind of a guy who was a masterful schemer and political intriguer. Pleasonton was the sort of guy who would start a fight on the playground and then step back and watch the chaos that he had started. And he was known for telling whoppers in the hope of promoting himself and his moribund career; his persistent lying and scheming ultimately cost him his command with the Army of the Potomac and found him banished to the hinterlands of Missouri, where, shockingly, he actually did quite well in running down the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price in the fall of 1864. He carried the mocking nickname of “The Knight of Romance” for good reason.

I recently came across an epic whopper by Pleasonton wherein he took credit for wounding Stonewall Jackson, a claim so outrageous as to have caused me to laugh out loud when I read it. This is Alfred Pleasonton’s account of the Battle of Chancellorsville, wherein he was clearly the hero of the battle (at least in his own mind):

In this campaign my command was the first cavalry division of the army of the Potomac, the first brigade of which during the battle was with General Stoneman on his raid towards Richmond, in rear of Lee’s army. With one brigade I preceded the 11th and 12th corps as far as Chancellorsville. The movements of the 5th, 11th, and 12th corps across the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers were very fine and masterly, and were executed with such secrecy that the enemy were not aware of them; for, on the 30th of April, 1863, I captured a courier from General Lee, commanding the rebel army, bearing a despatch from General Lee to General Anderson, and written only one hour before, stating to General Anderson he had just been informed we had crossed in force, when, in fact, our three corps had been south of the Rapidan the night previous, and were then only five miles from Chancellorsville. The brilliant success of these preparatory movements, I was under the impression, gave General Hooker an undue confidence as to his being master of the situation, and all the necessary steps were not taken on his arrival at Chancellorsville to insure complete success. The country around Chancellorsville was too cramped to admit of our whole army being properly developed there; and two corps, the 11th and 12th, should have been thrown on the night of the 30th of April to Spotsylvania Court House, with orders to intrench, while the remainder of the army should have been disposed so as to support them. This would have compelled General Lee to attack our whole force or retire with his flank exposed, a dangerous operation in war, or else remain in position and receive the attack of Sedgwick in rear and Hooker in front, a still worse dilemma.

In the third day’s fight at Chancellorsville General Hooker was badly stunned by the concussion of a shell against a post near which he was standing, and from which he did not recover sufficiently during the battle to resume the proper command of the army. The plan of this campaign was a bold one, and was more judicious than was generally supposed from the large force General Hooker had at his command. There is always one disadvantage, however, attending the sending off of large detachments near the day of battle. War is such an uncertain game it can scarcely be expected that all the details in the best devised plans will meet with success, and unless a general is prepared and expects to replace at once, by new combinations, such parts of his plans as fail, he will be defeated in his campaign, and as these changes are often rapid, he cannot include his distant detachments in his new plans with any certainty, and the doubt their absence creates, reduces the army he can depend on to the actual number of men he has in hand. If General Hooker had not been injured at the commencement of the final battle, I am not certain his splendid fighting qualities would not have won for him the victory. It was in this battle that with three regiments of cavalry and twenty-two pieces of artillery I checked the attack of the rebel General Stonewall Jackson after he had routed the 11th corps. Jackson had been moving his corns of twenty-five or thirty thousand men through the woods throughout the day of the 2d of May, 1863, from the left to the right of our army, and about six o’clock in the evening he struck the right and rear of the 11th corps with one of those characteristic attacks that made the rebel army so terrible when he was with it, and which was lost to them in his death. In a very short time he doubled up the 11th corps into a disordered mass, that soon sought safety in flight. My command Of three cavalry regiments and one battery of six guns happened to be near this scene; and perceiving at a glance that if this rout was not checked the ruin of the whole army would be involved, I immediately ordered one of my regiments to charge the woods from which the rebels were issuing and hold them until I could bring some guns into position; then chaining several squadrons into our flying masses to clear ground for my battery, it was brought up at a run, while staff officers and troops were despatched to seize from the rout all the guns possible. The brilliant charge of the regiment into the woods detained the rebels some ten minutes, but in that short time such was the energy displayed by my command I placed in line twenty-two pieces of artillery, double-shotted with canister, and aimed low, with the remainder of the cavalry supporting them. Dusk was now rapidly approaching, with an apparent lull in the fight, when heavy masses of men could be seen in the edge of the woods, having a single flag — and that the flag of the United States — while at the same time they cried out, “Don’t shoot; we are friends!” In an instant an aide-de-camp galloped out to ascertain the truth, when a withering fire of musketry was opened on us by this very gallant foe, who now dropped our ensign, displayed ten or twelve rebel battle flags, and with loud yells charged the guns. I then gave the command “fire,” and the terrible volley delivered at less than two hundred yards’ distance caused the thick moving masses of the rebels to stagger, cease from yelling, and for a moment discontinue their musket fire; but they were in such numbers, had such an indomitable leader, and they had so great a prize within their reach, that they soon rallied and came on again with increased energy and force, to be met by the artillery, served well and rapidly, and with such advantage that the rebels were never able to make a permanent lodgement at the guns, which many of their adventurous spirits succeeded in reaching. This fight lasted about an hour, when a final charge was made and repulsed; they then sullenly retired to the woods. It was at this time that General Jackson was mortally wounded; and as the rebel authorities have published he had been killed by his own men, I shall mention some facts of so strong a character as to refute this statement. Soon after the last attack I captured some of the rebel soldiers in the woods, and they told me it was Jackson’s corps that had made this fight; that Jackson himself had directed it, and had been mortally wounded, and that their loss was very heavy. I have since met rebel officers who were then engaged, and they corroborated the above statement, and they added, that it was known and believed among Jackson’s men that he had been mortally wounded by our own fire. Again, one of my own officers who had been taken prisoner in that engagement told me, after he was exchanged, that he had been taken up to Jackson soon after his capture; that Jackson questioned him about our force, and that he then was not far from our lines. This clearly proves that Jackson was on the field, in command, and had not been wounded up to and until after the fight had commenced. Now, when it is remembered the entire front of my line did not occupy six hundred yards; that the opposing forces were in open ground, not three hundred yards from each other, and so close that no reconnaissance in front was necessary by an officer of Jackson’s rank, and taken, in connection with the fact that the fierce characteristic of the attacks of the man did not cease until he was wounded, and were not renewed after he was, the conclusion is simple, natural, and forcible that Jackson commanded and fell in his attack on our guns. In justice to the high character, as a general, of Jackson, I am free to admit that had he not been wounded, and had made another attack, as he undoubtedly would have done, he would have carried my position, for my losses had already disabled more than half my guns, and the few that were left could have easily been overpowered. There seemed a providential interference in Jackson’s removal at the critical time in which it occurred, for the position fought for by him commanded and enfiladed our whole army; and had he won it on the rout of the 11th corps, the disaster to us would have been irreparable.

Wow. There’s not much else to say but wow. Too bad this is all fiction….

It bears noting that George Stoneman intentionally left him behind when the Cavalry Corps went off on its raid during the Chancellorsville Campaign. Pleasonton should not have even been at Chancellorsville, but for the fact that Stoneman didn’t want him along on the expedition.

He reminds me of the Jon Lovitz “Lying Man” character from the 1990’s edition of Saturday Night Live:

This little prize is part of a very long letter that Pleasonton wrote to Sen. Benjamin F. Wade, the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, in the late fall of 1865, reporting on his activities in the Civil War. It’s a flight of fancy that is jam-packed with lie after self-aggrandizing lie that is epic even by Alf Pleasonton’s standards. As time progresses, I will probably put up some other bits and pieces of this doozie.

For now, though, enjoy this epic flight of fictional fancy by one of the great liars of the 19th Century.

Scridb filterBvt. Lt. Col. William Wallace Rogers, forgotten cavalryman

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Today, we have a forgotten cavalrymen post on Capt. William Wallace Rogers by his descendant, Capt. John Nesbitt, III, formerly of the U.S. Army. Rogers served with honor in the Civil War and in the post-war Regular Army.

Captain William Wallace Rogers descended from William and Ann Rogers who immigrated to Wethersfield, Connecticut by way of Virginia in the mid-1630s, and then to Long Island, where they were early settlers of Southampton (the Southampton Historical Museum is housed in the Rogers’ mansion built on the Rogers’ homestead by a descendent of Obadiah Rogers, a son of William and his wife). William is also considered a founder of Huntington, L.I., having been one of the men who negotiated the purchase of the land for Huntington with the Native Americans. From there, their son Noah went back across Long Island Sound as an early settler of Branford, Connecticut where Captain Rogers’ ancestors resided for almost 200 years before migrating to Pennsylvania. Captain Rogers’ great-grandfather was Samuel Rogers, Jr. who served three times as a Private in the Connecticut militia in the Revolution – twice volunteering and once conscripted. This story as supported by Private Rogers’ request for his pension, and related family stories, surly was passed down to Captain Rogers as a boy, as it was to this writer and descendent of Samuel Rogers, Jr. by his grandmother a niece of Captain Rogers who was born in 1890, the year Captain Rogers died.

Captain Rogers was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, November 15, 1832, the eldest son of Minor and Elizabeth (Fretz/Fratts/Fratz) Rogers. The personal “Record of Service of William W. Rogers, Captain 9th Infantry United States Army.” dated September 24, 1883 and written down at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, says of his Civil War military service that he “Enlisted as private in Company B. 3rd Penna., Cavalry , (60th Pennsylvania Volenteers (sic)) July 23, 1861.” This was in Philadelphia. And, further, that he was “Promoted-2nd Lieutenant, Company “C” 3rd Penna., Calvalry (sic). December 31, 1861. 1st Lieutenant Company “C” 3rd Penna., Cavalry July 17, 1862.” and “Captain Company “L” 3rd Penna., Cavalry May 1, 1863.” About the time of the latter date, and before the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union Army changed the designation Companies to Squadrons for the basic assignment and maneuver elements within the cavalry battalions.

Captain Rogers further writes that he: “Served with the 3rd Penna. Cavalry in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania from July 23, 1861 until February 6, 1864-and participated in the following named engagements.

WILLIAMSBURG, VA, May 6, 1862. FAIR OAKS, VA, June 15, 1862. Horse Killed and received injury by his falling upon my leg. SAVAGE STATION, VA, June 29, 1862. CHARLES CITY, CROSS ROADS, VA, June 30, 1862. MALVERN HILL, VA, July 1, 1862. RAPPAHANOCH STATION, VA, February 15, 1863. KELLYS FORD, VA, March 17, 1863. RAPIDAN STATION, VA, April 9, 1863. ELYS FORD, VA, May 1863. BRANDY STATION, VA, June 9, 1863. BEVERLY FORD, VA, June 1863. ALDIE, VA, June, 1863. GETTYSBURG, PA, July 2nd and 3rd, 1863. Received gun shot wounds through right breast and left shoulder, July 3, 1863. OAK HILL, VA, October, 1863. BRISTOL STATION, VA, October 14, 1863. NEW HOPE CHURCH, VA, November, 1863. PARKERS’ STORE, VA, November, 1863. (capitalization of actions are this writers for emphasis and clarity

)

Of the initial engagement, the battlefield of Williamsburg, May 4 & 5, 1863, Captain Rogers wrote his father in a letter of May 17, 1862 that “I saw them wounded in every imaginable manner. Some shot in the mouth, in the head, in the stomach, feet torn off and gashed in the thighs, or body, or arm with pieces of shell. Being shot myself the sight of their sufferings was awful. I soon got over it however and could look at the surgeons take off arms and legs and pile them in the field.” and described the action as follows, “Advance the charge yelling like demons or stand and receive a charge of the rebel infantry who also fought like heroes in these conflicts between infantry of both sides, the batteries would cease and yells would take the place of the thunder of guns and in this way it continued during the whole day in which regiments were nearly torn to pieces.” (Source: Curt Harley, copies of W.W. Rogers letters home to his father originally in the possession of Curt’s father Rogers Harley)

Just over a year later, the action at Brandy Station was a major cavalry battle that was a prelude to General Robert E. Lee moving North that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg. The cavalry battle at Gettysburg on the so called East Cavalry Field the afternoon of July 3, 1863, in which Captain Rogers was wounded, was both a major cavalry action and by many regarded as an important part of the Union victory that day.My interest in the Civil War goes back many years, to the mid-1950s, and was at least partially inspired by my grandmothers’ stories of the “thirteen Rogers relatives” who served in the Union Army “from a thirteen year old drummer boy,” thorough a Rogers “who was shot but the bullet could not be removed and who died in the 1870s when the bullet reached his heart,” to Captain William Wallace Rogers the oldest sibling of my grandmother’s mother and her twin sister who married George Harley. Even though I learned from her of Captain Rogers’ Civil War service and heroism at the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as his service among the Indian’s “out west” in the 1870s and 80s, I didn’t have any real substance to the story or his service until I came upon a newsstand copy of Blue & Grey Magazine for October, 1988. It was an “Anniversary Issue” and featured the article “Gettysburg: Cavalry Operations June 27-July 3, 1863,” by Ted Alexander.” Therein, pages 32, and 36-39, it was related as to the action on the “East Cavalry Field” that:

At 1 p.m. ”…the artillery barrage that preceded “Pickett’s Charge” began and was distinctly heard by all the troopers.

“At 2 p.m., (John B.) McIntosh (commanding the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry) decided to probe his front in order to determine the strength of his opponent. A dismounted skirmish line from the 1st New Jersey moved out about half a mile toward the Rummel farm. This prompted a counter movement by the Confederates at the Rummel farm and soon a brisk fight was underway as the opposing lines shot it out from behind parallel fence lines. Soon the Jerseymen were reinforced by two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania (one of which, “L”, was commanded by Captain Rogers) and the Purnell Legion, all of which were dismounted and held the left,”

Reading on it is reported, “Reinforcements should have meant Colonel J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade, but that would take time since it was several miles away. Custer (newly promoted Gen. George A. Custer) was nearer but heading south to join Kilpatrick near the Round Tops. Therefore, General David McM. Gregg overrode Custer’s marching orders and sent him to help McIntosh take on the Rebels at Rummel’s farm. Custer, sensing this was where the action was, did not protest.”

And that, “A little after 3 p.m., the Federals noticed sunlight reflecting off something in the distance along Cress Ridge. It shone from the drawn sabers of (Wade) Hampton’s and (Fitzhugh) Lee’s brigades, massed in attack formation…Lieutenant William Brooke-Rawle of the 3rd Pennsylvania recalled, “In close columns of squadrons, advancing as if in review, with sabres (sic) drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight, the spectacle called forth a murmur of admiration. It was indeed a memorable one.”

Then, “As the gray riders advanced, Gregg personally ordered Colonel Charles Town to take his 1st Michigan out to meet them.” And, Town being quite ill, “…Custer rode up to lead them. The gait of both columns increased as they drew nearer, first at a trot then a gallop.”

When, “The front rank of the 1st Michigan wavered for a moment, then Custer yelled, “Come on you Wolverines!” and the entire regiment spurred ahead.”

Gregg’s troops, and in particular Custer’s Wolverines, were outnumbered by General J.E.B. Stuart’s charging legions, and, “Although the Wolverines numbered less than 500 against more than six times that many, their wedge-like penetration parted Hampton’s formation.”

Fortunately, help was close at hand, “While the 1st Michigan slugged it out with Hampton, who by now was supported on the flanks by Lee and (John R.) Chambliss, additional bodies of Federals that had been scattered about the field rallied and struck the Confederates on the flanks. Among them were two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania, under Captain Charles Treichel and Lieutenant William Rogers (should be Captain), who struck the Confederate right. Even Colonel McIntosh and about 20 officers and men from his headquarters group charged in to assist Treichel and Rogers.”

With the support of squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania also coming in from the Confederate left flank, the charge of Stuart’s brigades was turned back, in spite of the fact that, “Stuart had over 6000 men, a large proportion of them which he committed to the fight. Gregg had about 5000 men but only about 3000 saw action.”

Captain Rogers returned to service with the 3rd PA Cavalry following his recovery from his wounds September 28, 1863. February 6, 1864 he was appointed a Captain in the Veterans Reserve Corps serving in Washington, D.C. He was promoted for his gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Gettysburg, his highest brevet rank being Lt. Col. as of March 13, 1865.

Curt Harley, a cousin of this reporter, wrote in 2006 that Captain Rogers was an officer of the honor guard for President Lincoln both at his 2nd inauguration and while he lay in state. He also says: that Captain Rogers was in command of the cavalry detail at Ford Theater and was one of the first to notice that Lincoln was shot; that he was a good friend of Custer; and, that he was also a friend of Buffalo Bill Cody. Captain Rogers, in his own report of his service of 1883, writes that he served in Washington, D.C. during 1864 and until 1867, including in the Office of the Military Governor of Washington, D.C.

He continued in the Army for the rest of his career, 1867 until 1869 in Tennessee in charge of troops during the Reconstruction Era with the 45th Infantry and the 14th Infantry respectively, and then in April, 1870 at Crow Creek Agency, Dakota as Acting Assistant Quartermaster and A.C.S. (Acting or Assistant Chief of Staff) and subsequently commanding Company B, 14th Infantry.

Now Regular Army First Lieutenant Rogers’ personally written “Record of Service” records that “5/22/1871 On duty with Company G. 9th Inf. 1st Lieut. A.C.S. Fort D.A. Russell Wyo.” The formal certificate of his appointment as an officer in the Regular Army, of which I have a copy from Rogers Harley, reads “…William W. Rogers, I have nominated, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, do appoint him First Lieutenant in the Ninth Regiment of Infantry in the service of the United States: to rank as such from the twenty second day of May eighteen hundred and seventy one,…” and is signed by the Secretary of War and President U.S. Grant. Over the next sixteen years Captain Rogers and his family served with the Ninth Infantry on posts in Nebraska and Wyoming- the overall command being called the Department of the Platt.

First Lieutenant Rogers was married- his first wife’s name was Elizabeth (Lizzie). They had a daughter Florence (Floe) while serving in Tennessee, and apparently an older son Horace Byron. Floe died young at Fort D.A. Russell, Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory on July 21, 1871. Floe was first buried there “where the prairie winds will sweep over her grave” (a quote of First Lieutenant Rogers included in a letter of Rogers Harley in January 15, 1992 to my mother Dorothy Nesbitt). Lieutenant Rogers’ wife Lizzie died April 30, 1874, also at Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, and was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery, Omaha, Nebraska. In 1875 Floe was reburied beside her mother. Between these two tragic Cheyenne tours Lieutenant Rogers served at Sidney Barracks in southwest Nebraska. His son Horace it would also seem died rather young.From “Nov. 28, 1875 to Sept. 12, 1876” Lieutenant Rogers writes in his personal “Record of Service” of September 24, 1883 that he was “Commanding Camp Sheridan, Neb., and Company F. 9th Infantry.” This conforms to the History of the Ninth Infantry: 1799-1909, by Capt. Fred R. Brown, Adjutant, Ninth Infantry (1909), page 116 where it is recorded as follows:

“Company F left post (i.e. Camp Sheridan, Neb.) on May 8th, under command of First-Lieutenant W. W. Rogers, Ninth Infantry, to scout the country between the post and Custer City, with Company K. Second Cavalry. The company returned from Custer City via Camp Robinson, Nebraska, on the 29th of May. Distance marched, 418 miles.”

On a driving trip to visit western U.S. National Parks, including in the Black Hills and the Little Bighorn Battlefield, my wife and I recently visited those locations where Lieutenant, and later, Captain Rogers served in the Department of the Platt in the 1870s and 80s where there are still structures and such to visit. The Camp Sheridan site lies east of Chadron and north of Hay Springs in Nebraska, and south of Oglala which is due north in South Dakota, but nothing remains of the camp to visit. We followed Nebraska Route 20, the Crazy Horse Memorial Highway, east from Fort Robinson turning onto Highway 385 north, the Gold Rush Highway, heading for Custer City, South Dakota just before reaching Chadron. For more background, the role of Camp Sheridan and its relationship to Fort Robinson in the 1870’s is described below:

CAMP SHERIDAN AND SPOTTED TAIL AGENCY

About ten miles north are the sites of Spotted Tail Agency and Camp Sheridan. Named for Brule Sioux Chief Spotted Tail, the agency was built in 1874 to supply treaty payments, including food, clothing, weapons, and utensils, under the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. The army established Camp Sheridan nearby to protect the agency. A similar arrangement prevailed for the Ogalala Sioux at Red Cloud Agency and Camp Robinson forty miles west.

Spotted Tail Agency was generally quiet and peaceful throughout the Indian War of 1876-77. Crazy Horse surrendered there on September 4, 1877, after fleeing Red Cloud Agency. He was stabbed to death the next evening while being imprisoned at Camp Robinson, but his parents returned his body to Camp Sheridan for burial.

On October 29, 1877, Spotted Tail’s Brules were moved to present South Dakota. In 1878 they occupied the Rosebud Agency, where they live today. Camp Sheridan, with a peak garrison of seven companies of soldiers, was abandoned on May 1, 1881.

I had been wondering why Lieutenant Rogers’ “…scout (of) the country between the post (Camp Sheridan) and Custer City…” of May, 1876 received such specific attention in the History of the Ninth Infantry: 1799-1909, by Capt. Fred R. Brown (1909) supra. It is not the case for that work to give a routine “scout” such detailed attention. At the same time I was just finishing Thom Hatch’s recently published, early in 2015 by St. Martins Press, The Last Days of George Armstrong Custer, subtitle “The True Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.” When I connected the dots so to speak as I was finalizing this manuscript, I realized that Lieutenant Rogers, Co. F of the 9th Infantry and Company K, 2nd U.S. Cavalry weren’t just on a routine “scout”, but were undertaking what we would term today a Reconnaissance in Force. The reason, to be sure that the territory south of the Black Hills was secure from “hostile Indians” as the three prong approach into southeastern Montana of U.S. forces got underway in May of that year. This involved General Crook moving up the Rosebud Creek from northeast Wyoming, General Terry and Lt. Col. Custer coming from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory and moving due west and Colonel Gibbons coming from Fort Ellis to the west in Montana along the Yellowstone River. The objective, to find and destroy “hostile Indians” who would not peacefully return to their assigned reservations, and ultimately to converge on the confluence of the Rosebud and the Yellowstone in Montana. This was an opening phase of the Indian War of 1876-1877. General Crook would fight the Battle of the Rosebud and turn back. Lt. Col. Custer and five companies, of his men of the 7th Cavalry, Companies C, E, F, I and L, would go on to lose their lives in the Battle of the Little Bighorn of that June 25, 1876. For most in the Army and of the country, the death of Custer and his men at the Little Bighorn came as a shock, and logically this would have been even more so for Lieutenant Rogers. The man of then modern legend who he had fought in support of at Gettysburg on that hot and pivotal July day in 1863, who by family tradition he considered a good friend as they crossed paths “out west on the great plains” in the early years of the 1870s, and, as has been pass down in our family, had discussed going into business ventures together when they eventually retired from the service was not only defeated, but was killed. It had to be one of the great shocks of his life, though not on a par with the loss of his little Floe and two years later his wife Elizabeth.

But change was coming for Lieutenant Rogers and his command. By his own record, he was less than three months from returning east. By “September 12, 1876” he was “On duty at Fort Lavaunio (hand corrected to Fort Laramie), Wyo., Comd’y. Co., F. 9th Inf.”

While it seems rather a fast trip, Lieutenant Rogers and Helen King Dewey, a relative of Admiral Dewey, were married on September 19, 1876 at Unity Church, Chicago by the Reverend Robert Collyer. Interestingly, General L. P. Bradley who married one of Helen’s three sisters had been Lieutenant Colonel of the 9th Infantry Regiment (source: manuscript Pvt, Dewey Rogers 1881-1900: Co. “G”-9th Infantry U.S. Army by Rogers S. Harley (1991)). The newlyweds then went on to New York and other locations in the east where Lieutenant Rogers’ duties focused on recruiting for the Ninth Infantry.

Lieutenant Rogers and Helen then went west again, where he continued with the 9th Infantry, with which he would remain. As of “Dec. 16, 1878” he was “En-route to join Company F. 9th Infantry at Fort McKinney, Wyo.”, west of Buffalo, WY. By “March 31, 1880” he was “On duty at Fort Sidney, Neb., as Capt. Co., B. 9th Infantry.” Until “April 22, 1880” when he was “Enroute with Company B. 9th Infantry from Fort Sidney, Neb. to Fort Niobrara Neb., engaged in building the New post.” Helen and Captain Rogers’ only child, Dewey, was born July 22, 1881 at Ft. Niobrara, Nebraska where they served through April 13, 1883. By “Aug. 17, 1883” Captain Rogers and his family were at Fort Bridger, where he further writes in his personal “Record of Service”: “With Company engaged in repairing wagon road from Fort Bridger, Wyo., to Fort Thoruburg (sic, should be Thornburg)), Utah.” Regarding Fort Thornburg, During the summer of 1881 the military troops were established in Ashley Canyon for protection against Indians. Moving to Fort Thornburgh in December, 1881. The fort was abandoned in 1884 and part of the supplies taken to Fort Bridger”. (source: on-line copy of marker for Fort Thornburg).

In 1886 the 9th Infantry was reassigned to the Department of Arizona. This was very much hardship duty given the sever conditions of the climate and terrain. In 1887, for whatever reason, Captain Rogers requests and receives written official confirmation that he was wounded twice in action on July 3, 1863 (of which the family has a copy). Question: Was his health already declining and he was looking ahead to retiring for medical reason, and/or possibly the memories of the young of the day about the Battle of Gettysburg and his service a quarter of a century on needed such written documentation? Today we would say that he was at the least entitled to the Purple Heart medal. He retired from the service because of severe illness in 1889, and he, Helen and Dewey settled in Chicago. Due to his illness, Captain Rogers went to California hoping it would be helpful to his health. He died there in San Diego, December 14, 1890. In Brown, Supra, page 145, it is reported that “As indicating the severity of service, discomforts , and exhausting climate conditions in Arizona from 1886 to 1891, the regiment lost: Five Captains by retirement for disability, (one of whom died soon after): Two Captains by death, and one First Lieutenant by retirement for disability:…” and the list goes on. It would seem quite probable that the Captain who died soon thereafter is a reference to the death of Captain Rogers.

Following his wishes, Helen took Captain Rogers remains to Omaha, Nebraska, where he was buried in the Prospect Hill (Old) Cemetery, Lot 746, E1/2, beside his first wife, Elizabeth, and their young daughter, Floe. Helen would go on to Tacoma, WA where she had close relatives. Dewey Rogers would graduate from high school with Honors in Tacoma in 1898. Not being happy with office work, his mother had at first objected, but finally gave Dewey permission to join the Army. “His ultimate dream was to earn a commission in the 9th Infantry…He could not, however, because of quotas and the political prestige required, gain a place at West Point.” Dewey joined the army in Portland January 10, 1900, with the goal of becoming an officer in the 9th Infantry. He was posted to San Francisco, and February 17, 1900 was shipped out to the Philippines where he joined Company “G” of the 9th Infantry. On June 27, 1900 the 9th Infantry sailed from Manila for China to join the International Force fighting the Chinese Boxers. Tragically, Dewey died July 13, 1900 in China storming the walls of Tien Tsin during the Boxer Rebellion. In 1901 he was buried in the Tacoma (Washington) Cemetery, Section 2, Sub-section “E”, Lot #2. The source of this information after Captain Rogers’ death comes from the manuscript, Pvt. Dewey Rogers, 1881-1900, Company “G”- 9th Infantry U.S. Army, by Rogers S. Harley (1991).Thanks to Captain Nesbitt for his contribution, and thanks also to him for providing the images that appear here.

Here’s to Bvt. Lt. Col. William Wallace Rogers, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filterBrig. Gen. Alfred N. Duffié

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Born Napoléon Alexandre Duffié, he carried the nickname “Nattie.” Duffié was born in Paris, France, on May 1, 1833, the son of a well-to-do bourgeois French sugar refiner who distilled sugar from beets. [1] At age 17, Duffié enlisted in the French 6th Regiment of Dragoons. Six months later, he was promoted to corporal, and received a second promotion, this time to sergeant, in March 1854. He served in French campaigns in Africa and in the Crimean War from May 1, 1854, to July 16, 1856, and received two decorations for valor during this period.

In 1855, the 6th Regiment of Dragoons, along with two other mounted units, made a brilliant cavalry charge at the Battle of Kanghil, near the Black Sea port of Eupatoria in the Ukraine, leading to the issuance of his decorations. In February 1858, Duffié was made first sergeant in the 6th Dragoons and then transferred to the 3d Regiment of Hussars. Although he would have been eligible for discharge from the French Army in 1859, Duffié signed on for another seven-year enlistment that spring after being graded “a strong man capable of becoming a good average officer.”

On June 14, 1859, Duffié received a commission as second lieutenant in the 3d Regiment of Hussars. Just two months later, Duffié tried to resign his commission, stating a desire to go into business. He had met thirty-two-year-old Mary Ann Pelton, a young American woman serving as a nurse in Europe’s charnel houses. Duffié’s regimental commander rejected the attempted letter of resignation, stating his “regrets that this officer so little appreciates the honor of recently having been promoted sous-lieutenant, and that he would prefer a commercial position to that honor.” [2] When the French army refused to allow Duffié to resign, he deserted and fled to New York with Miss Pelton. He was listed as absent without leave and court-martialed in 1860. He was convicted and sentenced to dismissal without benefits for desertion to a foreign country and stripped of his medals. On December 20, 1860, by decree of Emperor Napoléon III, Duffié was sentenced, in absentia, to serve five years in prison for deserting and was dishonorably discharged from the French army. [3]

After arriving in New York, he adopted the first name Alfred, perhaps trying to disguise his true identity from prying eyes. He also married Miss Pelton, the daughter of a wealthy and influential New York family. Mary Ann Duffié’s father was a dealer in boots and shoes and shoemakers’ supplies, and was “an energetic and successful businessman” who lived in an enclave of strong abolitionists in Staten Island.[4] When the Civil War broke out, Duffié received a commission as a captain in the 2d New York Cavalry. He quickly rose to the rank of major, and was appointed colonel of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry in July 1862.[5]

Duffié took great pains to hide his military history, spinning an elaborate web of lies, convincing all that cared to hear his story that he was the son of a French count, and not a humble sugar refiner. He changed the reported date of his birth from 1833 to 1835. He claimed that he had attended the preparatory Military Academy at Vincennes, that he had graduated from the prestigious military college of St. Cyr in 1854, and that he had served in Algiers and Senegal as lieutenant of cavalry.[6]

Duffié also claimed that he had been badly wounded at the Battle of Solferino in the War of Italian Independence in 1859, a conflict between the forces of Austria on one side and the allied forces of Piedmont, Sardinia, and France on the other. Solferino was a huge and bloody affair, involving more than 300,000 soldiers and nearly 40,000 casualties. However, his unit, the 3d Hussars, was not part of the Army of Italy and did not fight at Solferino. Although Duffié said that he had received a total of eight wounds in combat, his French military records do not suggest that he ever received a combat wound. He also asserted that he had received the Victoria Cross from Queen Victoria herself.

Finally, Duffié claimed that he had come to the United States to take the waters at Saratoga Springs, not because he had deserted the French army and fled to America in the company of a woman who was not his wife. Perhaps the Peltons created the myth of Alfred Duffié, French nobleman and war hero, to make their new son-in-law more palatable to their prominent social circles. Because of his martial bearing, he soon persuaded both his superior officers and the men who served under him that he had noble roots and a superb military pedigree.[7]

“Confronting us, he presents the aspect of the beau ideal soldat . . .with his tall symmetrical form erect in saddle and severe facial expression emphasize by a mustache and goatee of formal cut waxed to a point a la militaire,” observed a war correspondent. “A Frenchman I judged him on sight, from his tout ensemble, and his first utterance, which launched without instant delay, proved my surmise correct.”[8] He wore an unusual uniform of his own design, based closely upon the attire of the French Chasseurs, knee boots, and an ornately embroidered cap patterned after the French Chasseur design.[9]

“Confronting us, he presents the aspect of the beau ideal soldat . . .with his tall symmetrical form erect in saddle and severe facial expression emphasize by a mustache and goatee of formal cut waxed to a point a la militaire,” observed a war correspondent. “A Frenchman I judged him on sight, from his tout ensemble, and his first utterance, which launched without instant delay, proved my surmise correct.”[8] He wore an unusual uniform of his own design, based closely upon the attire of the French Chasseurs, knee boots, and an ornately embroidered cap patterned after the French Chasseur design.[9]

Duffié spoke fractured English. “His attempts were interlarded with curious and novel expletives, which were very amusing.”[10] In assuming a new command, the Frenchman would say, “You no like me now. You like my bye and bye.” He was right. Before long, they would follow him when he ordered a charge. “Once, in preparing to make a charge where the situation looked a little desperate,” recalled a New Yorker, Duffié “encouraged his men, who were little more than boys, by saying, ‘You all have got to die sometime anyway. If you die now you won’t have to die again. Forward!’ His charge was successful.”[11]

Although the Gallic colonel got off to a rough start with his Rhode Islanders, he soon won them over. The men of his brigade liked him. “Duffié is in command of the Brigade. He is a Frenchman,” observed Albinus Fell of the 6th Ohio Cavalry, “he is a bully little cuss.”[12] Another predicted that the Frenchman would quickly receive a promotion and leave the 1st Rhode Island. “He is a bully man,” observed Sgt. Emmons D. Guild of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. “I tell you he will not stay long, so you will have to look out if you want to see him. His name is A. N. Duffié.”[13] Duffié’s experience showed, and he performed competently if not spectacularly. “Whatever may have been the faults of Colonel Duffié,” recorded his regimental sergeant major, “there is no gainsaying the fact that he was probably the best regimental cavalry drill-master and tactician in the army.”[14] His veteran brigade, which saw heavy action during the Second Bull Run Campaign of 1862, consisted of the 1st Rhode Island, the 1st Massachusetts, 6th Ohio, and 4th New York.

Duffié performed admirably at the March 17, 1863 Battle of Kelly’s Ford while commanding his brigade, in what was unquestionably his finest hour. He was recommended for promotion after his good fight that day, and when his division commander, Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell, was scapegoated for the Union defeat at Chancellorsville and unceremoniously relieved of command of his division and shunted off to West Virginia. As the senior officer in the division, the Frenchman became commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Second Cavalry Division, proving the truth of the Peter Principle: the Gallic sergeant was in way over his head. Unduly cautious and insistent on obeying his orders to the letter at the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, Duffié permitted his division’s advance to be held off for most of a day by a single regiment of Confederate cavalry, the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry. After finally brushing the grayclad horsemen aside, Duffié and his division arrived at Brandy Station too late to make a difference in the outcome of the battle. A few days later, when the Cavalry Corps was restructured, the Frenchman was relieved of divisional command and returned to command the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry.

Duffié returned to the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. “I know that there was not the most cordial feeling between him and the controlling officers in the cavalry,” recalled a Northern horseman. “I suspected that he was more or less a thorn in the side of the higher officers. He was not companionable with them; did not think as they did; had little in common, and, was perhaps inclined to be boastful.”[15] However, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, had other plans for ridding himself of the Frenchman.

On June 17, 1863, Pleasonton dispatched Duffié and the 1st Rhode Island on a reconnaissance to Middleburg, in Virginia’s lush Loudoun Valley. The vastly outnumbered Rhode Islanders were cut to pieces. They lost 6 killed, 9 wounded, and 210 missing and captured, leaving a fine regiment gutted. Pleasonton apparently sacrificed the 1st Rhode Island to rid himself of a hated foreigner.[16] “Had any native born officer been in command the regiment would, without doubt, have cut its way out that night,” observed one of his officers, “[but] Colonel Duffié was a Frenchman, he had received positive orders [to remain in the town that night] and thought it his duty to obey them.” When the Gallic colonel reported to Hooker after escaping from Middleburg, he learned that he had been recommended for immediate promotion to brigadier general, prompting him to declare, “My goodness, when I do well they take no notice of me. When I go make one bad business, make one fool of myself, they promote me, make me General!”[17] John Singleton Mosby, the notorious Confederate partisan commander, offered his opinion of the Frenchman’s leadership skills: “Duffié’s folly is an illustration of the truth of what I have often said—that no man is fit to be an officer who has not the sense and courage to know when to disobey an order.”[18]

Several weeks earlier, Hooker had endorsed a promotion for Duffié as a consequence of his good work at Kelly’s Ford. A few days after the debacle at Middleburg, President Lincoln forwarded a letter to Secretary of War Stanton recommending that Duffié be promoted as a consequence of the Frenchman’s good service at Kelly’s Ford.[19] In spite of the mauling received by the Rhode Islanders, Duffié was promoted to brigadier general and was transferred out of the Army of the Potomac in a classic bump upstairs. He never commanded troops in the Army of the Potomac again. He ended up under Averell’s command again, leading a brigade of cavalry in the Department of West Virginia. When the division commander was badly wounded, Duffié assumed command of the division, while Averell served as chief of cavalry in the Army of the Shenandoah. The two men came into conflict as a result of the clumsy command structure.

In September 1864, just after the important Union victories at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, the new leader of the Army of the Shenandoah, relieved both Averell and Duffié from command. Sheridan directed Duffié to go to Hagerstown, Maryland, to await further orders.[20] On October 21, 1864, Duffié boarded an army ambulance to go see Sheridan about getting another command. Sheridan wanted Duffié to equip and retrain another cavalry force, duty for which the Gallic general was abundantly qualified.[21] After receiving his instructions from Sheridan, on October 24, as Duffié was headed back to Hagerstown to prepare for his new assignment, Mosby’s guerrillas fell upon the Frenchman’s wagon train. Mosby captured Duffié and quickly sent him back to Richmond as a prisoner of war. He sat out the rest of the war in a prisoner of war camp in Danville and was not exchanged until March 1865. After Duffié’s capture, Sheridan put an exclamation point on the Frenchman’s career in the U.S. Army. “I respectfully request his dismissal from the service,” sniffed Sheridan in a letter to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, “I think him a trifling man and a poor soldier. He was captured by his own stupidity.”[22] Duffié never served in the U.S. Army again, although he remained in public service for the rest of his life.

In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Duffié as U.S. consul to Spain, and sent him to Cadiz, on the Iberian Peninsula’s southwest seacoast. While he served in Spain, the Frenchman contracted tuberculosis, which claimed his life in 1880. Because of his conviction for desertion, Duffié never was able to return to his native France. His body was brought home and buried in his wife’s family plot in Fountain Cemetery in Staten Island, N.Y. Unfortunately, the cemetery was abandoned long ago, and the grave is badly overgrown with vegetation. It is nearly impossible to find, and is as forgotten to history as the proud soldier that rests there. The veterans of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, who remained loyal to their former commander, raised money to erect a handsome monument to Duffié in the North Burying Ground in Providence. Capt. George Bliss, who commanded a squadron in the 1st Rhode Island, wrote a lengthy and eloquent tribute to Duffié that was published and distributed to the veterans of the regiment. [23]

In addition to being a flagrant fraud, Alfred Duffié was incompetent to command anything larger than a regiment, and even then, he was only marginally successful. Other than his one good day at Kelly’s Ford, Duffié left no real mark. But his fraud is a fascinating study of the efforts to reinvent the life’s story of a French deserter who became a general in the United States Army. Here’s to Nattie Duffié, forgotten cavalryman.

With gratitude to Jean-Claude Reuflet, a French descendant of Duffié’s, for providing me with much of the material that appears in this profile.

[1] His father, Jean August Duffié, served as mayor of the village of La Ferte sous Juarre. At least one contemporary source states that the Duffié family had its roots in Ireland, and that the family fled to France to escape Oliver Cromwell’s Reign of Terror. See Charles Fitz Simmons, “Hunter’s Raid,” Military Essays and Recollections, Papers Read Before the Commandery of the State of Illinois Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States 4 (Chicago: 1907), 395–96.

[2] Napoléon Alexandre Duffié Military Service Records, French Army Archives, Vincennes, France. The author is grateful to Jean-Claude Reuflet, a relative of Duffié’s, for making these obscure records available and for providing the author with a detailed translation of their contents.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jeremiah M. Pelton, Genealogy of the Pelton Family in America (Albany, N.Y.: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1892), 565. The true state of the facts differs dramatically from the conventional telling of Duffié’s life, as set forth in Warner’s Generals in Blue.

[5] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), 131–32.

[6] A document prepared by Duffié’s son indicates that Duffié attended the cadet school at Versailles, that he took and passed the entrance examinations for the Military College of St. Cyr, and that he was admitted to St. Cyr in 1851. Daniel A. Duffié claimed that his father dropped out of St. Cyr after a year to enlist in the 6th Regiment of Dragoons. Procuration executed by Daniel A. Duffié, heir of Jean August Duffié, March 16, 1885, Pelton-Duffié Family Papers, Staten Island Historical Society, New York, N.Y.

[7] For an example of the elaborate ruse spun by Duffié, George N. Bliss, “Duffié and the Monument to His Memory,” Personal Narratives of Events in the War of the Rebellion, Being Papers Read Before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society 6 (Providence: Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, 1890), 316–376. Bliss presents a detailed biographical sketch of Duffié that includes all of the falsehoods. Duffié himself apparently provided Bliss with most of his information. See pages 317–20 for the recitation of this litany of falsehoods.

[8] James E. Taylor, The James E. Taylor Sketchbook (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside, 1989), 134.

[9] Gregory J. W. Urwin, The United States Cavalry: An Illustrated History (Poole, Dorset: Blandford Press, 1983), 98–99.

[10] Benjamin W. Crowninshield, A History of the First Regiment Massachusetts Cavalry Volunteers (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1891), 113.

[11] William H. Beach, The First New York (Lincoln) Cavalry from April 19, 1861, to July 7, 1865 (New York: Lincoln Cavalry Association, 1902), 399.

[12] Fell to Dear Lydia, March 8, 1863.

[13] Emmons D. Guild to his parents, March 20, 1863, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Archives, Fredericksburg, Va. (FSNMP).

[14] Jacob B. Cooke, “The Battle of Kelly’s Ford, March 17, 1863,” Personal Narratives of Events in the War of the Rebellion, Being Papers Read Before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society 4 (Providence: Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society, 1887), 9.

[15] George Bliss, The First Rhode Island Cavalry at Middleburg (Providence, R.I.: privately published, 1889), 48.

[16] For a detailed examination, see Robert F. O’Neill, Jr., The Cavalry Battles of Aldie, Middleburg and Upperville: Small but Important Riots (Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard 1994), 66–76.

[17] Bliss, The First Rhode Island Cavalry at Middleburg, 50.

[18] John S. Mosby, Stuart’s Cavalry in the Gettysburg Campaign (New York: Moffatt, Yard, 1908), 71.

[19] Abraham Lincoln to Edwin M. Stanton, June 22, 1863, Pearce Civil War Collection, Navarro College Archives, Corsicana, Tex.

[20] O.R. vol. 37, part 2, 896–97.

[21] New York Times, October 7, 1864.

[22] O.R. vol. 43, part 2, 475.

[23] See Bliss, “Duffié and the Monument to His Memory.”

Kilpatrick’s shirt-tail skedaddle: The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads, March 10, 1865

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Conclusion of a series. Cross-posted at Emerging Civil War.