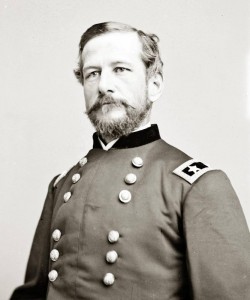

It’s an open question as to who was the worst, biggest, most pathological liar: Alfred Pleasonton or Phil Sheridan. Both were incapable of telling the truth, and both were known for prevaricating in the interest of self-promotion. As I have described him here previously, Pleasonton was a lead from the rear kind of a guy who was a masterful schemer and political intriguer. Pleasonton was the sort of guy who would start a fight on the playground and then step back and watch the chaos that he had started. And he was known for telling whoppers in the hope of promoting himself and his moribund career; his persistent lying and scheming ultimately cost him his command with the Army of the Potomac and found him banished to the hinterlands of Missouri, where, shockingly, he actually did quite well in running down the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price in the fall of 1864. He carried the mocking nickname of “The Knight of Romance” for good reason.

It’s an open question as to who was the worst, biggest, most pathological liar: Alfred Pleasonton or Phil Sheridan. Both were incapable of telling the truth, and both were known for prevaricating in the interest of self-promotion. As I have described him here previously, Pleasonton was a lead from the rear kind of a guy who was a masterful schemer and political intriguer. Pleasonton was the sort of guy who would start a fight on the playground and then step back and watch the chaos that he had started. And he was known for telling whoppers in the hope of promoting himself and his moribund career; his persistent lying and scheming ultimately cost him his command with the Army of the Potomac and found him banished to the hinterlands of Missouri, where, shockingly, he actually did quite well in running down the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price in the fall of 1864. He carried the mocking nickname of “The Knight of Romance” for good reason.

I recently came across an epic whopper by Pleasonton wherein he took credit for wounding Stonewall Jackson, a claim so outrageous as to have caused me to laugh out loud when I read it. This is Alfred Pleasonton’s account of the Battle of Chancellorsville, wherein he was clearly the hero of the battle (at least in his own mind):

In this campaign my command was the first cavalry division of the army of the Potomac, the first brigade of which during the battle was with General Stoneman on his raid towards Richmond, in rear of Lee’s army. With one brigade I preceded the 11th and 12th corps as far as Chancellorsville. The movements of the 5th, 11th, and 12th corps across the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers were very fine and masterly, and were executed with such secrecy that the enemy were not aware of them; for, on the 30th of April, 1863, I captured a courier from General Lee, commanding the rebel army, bearing a despatch from General Lee to General Anderson, and written only one hour before, stating to General Anderson he had just been informed we had crossed in force, when, in fact, our three corps had been south of the Rapidan the night previous, and were then only five miles from Chancellorsville. The brilliant success of these preparatory movements, I was under the impression, gave General Hooker an undue confidence as to his being master of the situation, and all the necessary steps were not taken on his arrival at Chancellorsville to insure complete success. The country around Chancellorsville was too cramped to admit of our whole army being properly developed there; and two corps, the 11th and 12th, should have been thrown on the night of the 30th of April to Spotsylvania Court House, with orders to intrench, while the remainder of the army should have been disposed so as to support them. This would have compelled General Lee to attack our whole force or retire with his flank exposed, a dangerous operation in war, or else remain in position and receive the attack of Sedgwick in rear and Hooker in front, a still worse dilemma.

In the third day’s fight at Chancellorsville General Hooker was badly stunned by the concussion of a shell against a post near which he was standing, and from which he did not recover sufficiently during the battle to resume the proper command of the army. The plan of this campaign was a bold one, and was more judicious than was generally supposed from the large force General Hooker had at his command. There is always one disadvantage, however, attending the sending off of large detachments near the day of battle. War is such an uncertain game it can scarcely be expected that all the details in the best devised plans will meet with success, and unless a general is prepared and expects to replace at once, by new combinations, such parts of his plans as fail, he will be defeated in his campaign, and as these changes are often rapid, he cannot include his distant detachments in his new plans with any certainty, and the doubt their absence creates, reduces the army he can depend on to the actual number of men he has in hand. If General Hooker had not been injured at the commencement of the final battle, I am not certain his splendid fighting qualities would not have won for him the victory. It was in this battle that with three regiments of cavalry and twenty-two pieces of artillery I checked the attack of the rebel General Stonewall Jackson after he had routed the 11th corps. Jackson had been moving his corns of twenty-five or thirty thousand men through the woods throughout the day of the 2d of May, 1863, from the left to the right of our army, and about six o’clock in the evening he struck the right and rear of the 11th corps with one of those characteristic attacks that made the rebel army so terrible when he was with it, and which was lost to them in his death. In a very short time he doubled up the 11th corps into a disordered mass, that soon sought safety in flight. My command Of three cavalry regiments and one battery of six guns happened to be near this scene; and perceiving at a glance that if this rout was not checked the ruin of the whole army would be involved, I immediately ordered one of my regiments to charge the woods from which the rebels were issuing and hold them until I could bring some guns into position; then chaining several squadrons into our flying masses to clear ground for my battery, it was brought up at a run, while staff officers and troops were despatched to seize from the rout all the guns possible. The brilliant charge of the regiment into the woods detained the rebels some ten minutes, but in that short time such was the energy displayed by my command I placed in line twenty-two pieces of artillery, double-shotted with canister, and aimed low, with the remainder of the cavalry supporting them. Dusk was now rapidly approaching, with an apparent lull in the fight, when heavy masses of men could be seen in the edge of the woods, having a single flag — and that the flag of the United States — while at the same time they cried out, “Don’t shoot; we are friends!” In an instant an aide-de-camp galloped out to ascertain the truth, when a withering fire of musketry was opened on us by this very gallant foe, who now dropped our ensign, displayed ten or twelve rebel battle flags, and with loud yells charged the guns. I then gave the command “fire,” and the terrible volley delivered at less than two hundred yards’ distance caused the thick moving masses of the rebels to stagger, cease from yelling, and for a moment discontinue their musket fire; but they were in such numbers, had such an indomitable leader, and they had so great a prize within their reach, that they soon rallied and came on again with increased energy and force, to be met by the artillery, served well and rapidly, and with such advantage that the rebels were never able to make a permanent lodgement at the guns, which many of their adventurous spirits succeeded in reaching. This fight lasted about an hour, when a final charge was made and repulsed; they then sullenly retired to the woods. It was at this time that General Jackson was mortally wounded; and as the rebel authorities have published he had been killed by his own men, I shall mention some facts of so strong a character as to refute this statement. Soon after the last attack I captured some of the rebel soldiers in the woods, and they told me it was Jackson’s corps that had made this fight; that Jackson himself had directed it, and had been mortally wounded, and that their loss was very heavy. I have since met rebel officers who were then engaged, and they corroborated the above statement, and they added, that it was known and believed among Jackson’s men that he had been mortally wounded by our own fire. Again, one of my own officers who had been taken prisoner in that engagement told me, after he was exchanged, that he had been taken up to Jackson soon after his capture; that Jackson questioned him about our force, and that he then was not far from our lines. This clearly proves that Jackson was on the field, in command, and had not been wounded up to and until after the fight had commenced. Now, when it is remembered the entire front of my line did not occupy six hundred yards; that the opposing forces were in open ground, not three hundred yards from each other, and so close that no reconnaissance in front was necessary by an officer of Jackson’s rank, and taken, in connection with the fact that the fierce characteristic of the attacks of the man did not cease until he was wounded, and were not renewed after he was, the conclusion is simple, natural, and forcible that Jackson commanded and fell in his attack on our guns. In justice to the high character, as a general, of Jackson, I am free to admit that had he not been wounded, and had made another attack, as he undoubtedly would have done, he would have carried my position, for my losses had already disabled more than half my guns, and the few that were left could have easily been overpowered. There seemed a providential interference in Jackson’s removal at the critical time in which it occurred, for the position fought for by him commanded and enfiladed our whole army; and had he won it on the rout of the 11th corps, the disaster to us would have been irreparable.

Wow. There’s not much else to say but wow. Too bad this is all fiction….

It bears noting that George Stoneman intentionally left him behind when the Cavalry Corps went off on its raid during the Chancellorsville Campaign. Pleasonton should not have even been at Chancellorsville, but for the fact that Stoneman didn’t want him along on the expedition.

He reminds me of the Jon Lovitz “Lying Man” character from the 1990’s edition of Saturday Night Live:

This little prize is part of a very long letter that Pleasonton wrote to Sen. Benjamin F. Wade, the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, in the late fall of 1865, reporting on his activities in the Civil War. It’s a flight of fancy that is jam-packed with lie after self-aggrandizing lie that is epic even by Alf Pleasonton’s standards. As time progresses, I will probably put up some other bits and pieces of this doozie.

For now, though, enjoy this epic flight of fictional fancy by one of the great liars of the 19th Century.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

I often wondered where “Yeah, that’s the ticket” originated. Like you, all I can say is, Wow! Thank you Eric.

Shockingly inventive. Perhaps this will be the basis for the next O’Reilly book, “Killing Stonewall”….

Pleasonton may have been a grandstander but whoever wrote this not only forgot to sign it, he (or she) omitted to cite any proof or references. It is a smear piece without foundation. If it is true, then please provide a fact or two. This is mostly cheap shots at a man admired by his peers.

Pleasonton himself wrote it. And since Eric showed me the source, and I have a copy of it, I can verify its veracity. In addition, I also own a copy of a handwritten letter from the battery commander, James Huntingdon, in which he completely refutes Pleasonton’s claim to have placed that artillery – a claim which Pleasonton makes in several other writings as well – and says that Pleasonton is a complete liar and had NOTHING to do with the placement of the guns. Pleasonton’s biggest lies regard the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaign (the latter full of even more outrageous whoppers) and also regarding Meade following the Gettysburg battle. As Eric states above, Pleasonton’s just reward for his bombastic buffoonery was getting kicked out west by Grant. Grant didn’t want him around either.

Welcome back, old “Leather Breeches”. Until this past week, I was wondering if you ever were going to post again.

Pleasonton’s account of the action at Hazel Grove (Chancellorsville) was denounced as bombastic fiction by James F. Huntington of Battery H 1st Ohio Light. Huntington, Augustus Hamlin and Pennock Huey were the main post-war writers who attacked Pleasonton’s account. Huey’s cavalry was not sacrificed by Pleasonton but was sent to reinforce Howard. On its way, they rode into Stonewall’s troops. The affair at Hazel Grove was of a somewhat minor affair as there were actually few casualties. The artillery officers were never in agreement as to what batteries were actually present but Huntington took command of the 10th and 11th New York along with Battery H after Albert von Puttkammer fled the field. Puttkammer denied that charge but was court-martialed for that and other actions and was found guilty and dismissed. Certainly one can find accounts that might back some of what Pleasonton wrote but in general it was as Hamlin wrote “The Romances of Chancellorsville.” Besides Pleasonton, there were other liars in this affair. Lt. Lewis of the 10th New York tells some whoppers. Gen. Sickles conveniently blamed everything on the 11th Corps not withstanding that he opened a huge gap in the Union line by chasing the tail of the Confederates at Catherine’s Furnace. Sickles lied about his great “night attack” which was by all accounts a fiasco. (Sickles’ self serving remarks were a prelude to his Gettysburg remarks.)

I have researched the Hazel Grove attack quite closely as Capt. Huntington was my great great grandfather so I have some interest in this affair. There is a lot of literature that the veterans wrote about this attack. I would say that Eric is correct in judging Pleasonton as a liar. I will close with a Battery H resolution which I paraphrase.

“First, that no charge was ordered by General Pleasonton….”

Second, “that the charge neither had nor was intended to have any bearing on the defense of Hazel Grove…”

Third, “the charge was was originated and ordered by Major Huey as a means of escape for his regiment.

Fourth, that the charge was made fully, if not more than, half a mile from Hazel Grove…”

Fifth, “that Brigadier General Pleasonton deliberately falsified the record, or, in other words, positively and knowingly lied about his own troops, as well as our artillery; that he (Pleasonton) might be benefited and accepted honors that belonged to men that he had sworn to care for and protect in their rights as soldiers.” (William Parmelee, Battery H)