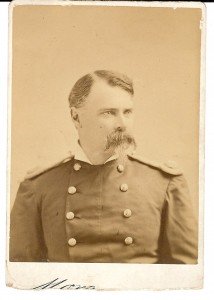

Today, we have a forgotten cavalrymen post on Capt. William Wallace Rogers by his descendant, Capt. John Nesbitt, III, formerly of the U.S. Army. Rogers served with honor in the Civil War and in the post-war Regular Army.

Captain William Wallace Rogers descended from William and Ann Rogers who immigrated to Wethersfield, Connecticut by way of Virginia in the mid-1630s, and then to Long Island, where they were early settlers of Southampton (the Southampton Historical Museum is housed in the Rogers’ mansion built on the Rogers’ homestead by a descendent of Obadiah Rogers, a son of William and his wife). William is also considered a founder of Huntington, L.I., having been one of the men who negotiated the purchase of the land for Huntington with the Native Americans. From there, their son Noah went back across Long Island Sound as an early settler of Branford, Connecticut where Captain Rogers’ ancestors resided for almost 200 years before migrating to Pennsylvania. Captain Rogers’ great-grandfather was Samuel Rogers, Jr. who served three times as a Private in the Connecticut militia in the Revolution – twice volunteering and once conscripted. This story as supported by Private Rogers’ request for his pension, and related family stories, surly was passed down to Captain Rogers as a boy, as it was to this writer and descendent of Samuel Rogers, Jr. by his grandmother a niece of Captain Rogers who was born in 1890, the year Captain Rogers died.

Captain Rogers was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, November 15, 1832, the eldest son of Minor and Elizabeth (Fretz/Fratts/Fratz) Rogers. The personal “Record of Service of William W. Rogers, Captain 9th Infantry United States Army.” dated September 24, 1883 and written down at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, says of his Civil War military service that he “Enlisted as private in Company B. 3rd Penna., Cavalry , (60th Pennsylvania Volenteers (sic)) July 23, 1861.” This was in Philadelphia. And, further, that he was “Promoted-2nd Lieutenant, Company “C” 3rd Penna., Calvalry (sic). December 31, 1861. 1st Lieutenant Company “C” 3rd Penna., Cavalry July 17, 1862.” and “Captain Company “L” 3rd Penna., Cavalry May 1, 1863.” About the time of the latter date, and before the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union Army changed the designation Companies to Squadrons for the basic assignment and maneuver elements within the cavalry battalions.

Captain Rogers further writes that he: “Served with the 3rd Penna. Cavalry in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania from July 23, 1861 until February 6, 1864-and participated in the following named engagements.

WILLIAMSBURG, VA, May 6, 1862. FAIR OAKS, VA, June 15, 1862. Horse Killed and received injury by his falling upon my leg. SAVAGE STATION, VA, June 29, 1862. CHARLES CITY, CROSS ROADS, VA, June 30, 1862. MALVERN HILL, VA, July 1, 1862. RAPPAHANOCH STATION, VA, February 15, 1863. KELLYS FORD, VA, March 17, 1863. RAPIDAN STATION, VA, April 9, 1863. ELYS FORD, VA, May 1863. BRANDY STATION, VA, June 9, 1863. BEVERLY FORD, VA, June 1863. ALDIE, VA, June, 1863. GETTYSBURG, PA, July 2nd and 3rd, 1863. Received gun shot wounds through right breast and left shoulder, July 3, 1863. OAK HILL, VA, October, 1863. BRISTOL STATION, VA, October 14, 1863. NEW HOPE CHURCH, VA, November, 1863. PARKERS’ STORE, VA, November, 1863. (capitalization of actions are this writers for emphasis and clarity

)

Of the initial engagement, the battlefield of Williamsburg, May 4 & 5, 1863, Captain Rogers wrote his father in a letter of May 17, 1862 that “I saw them wounded in every imaginable manner. Some shot in the mouth, in the head, in the stomach, feet torn off and gashed in the thighs, or body, or arm with pieces of shell. Being shot myself the sight of their sufferings was awful. I soon got over it however and could look at the surgeons take off arms and legs and pile them in the field.” and described the action as follows, “Advance the charge yelling like demons or stand and receive a charge of the rebel infantry who also fought like heroes in these conflicts between infantry of both sides, the batteries would cease and yells would take the place of the thunder of guns and in this way it continued during the whole day in which regiments were nearly torn to pieces.” (Source: Curt Harley, copies of W.W. Rogers letters home to his father originally in the possession of Curt’s father Rogers Harley)

Just over a year later, the action at Brandy Station was a major cavalry battle that was a prelude to General Robert E. Lee moving North that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg. The cavalry battle at Gettysburg on the so called East Cavalry Field the afternoon of July 3, 1863, in which Captain Rogers was wounded, was both a major cavalry action and by many regarded as an important part of the Union victory that day.My interest in the Civil War goes back many years, to the mid-1950s, and was at least partially inspired by my grandmothers’ stories of the “thirteen Rogers relatives” who served in the Union Army “from a thirteen year old drummer boy,” thorough a Rogers “who was shot but the bullet could not be removed and who died in the 1870s when the bullet reached his heart,” to Captain William Wallace Rogers the oldest sibling of my grandmother’s mother and her twin sister who married George Harley. Even though I learned from her of Captain Rogers’ Civil War service and heroism at the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as his service among the Indian’s “out west” in the 1870s and 80s, I didn’t have any real substance to the story or his service until I came upon a newsstand copy of Blue & Grey Magazine for October, 1988. It was an “Anniversary Issue” and featured the article “Gettysburg: Cavalry Operations June 27-July 3, 1863,” by Ted Alexander.” Therein, pages 32, and 36-39, it was related as to the action on the “East Cavalry Field” that:

At 1 p.m. ”…the artillery barrage that preceded “Pickett’s Charge” began and was distinctly heard by all the troopers.

“At 2 p.m., (John B.) McIntosh (commanding the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry) decided to probe his front in order to determine the strength of his opponent. A dismounted skirmish line from the 1st New Jersey moved out about half a mile toward the Rummel farm. This prompted a counter movement by the Confederates at the Rummel farm and soon a brisk fight was underway as the opposing lines shot it out from behind parallel fence lines. Soon the Jerseymen were reinforced by two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania (one of which, “L”, was commanded by Captain Rogers) and the Purnell Legion, all of which were dismounted and held the left,”

Reading on it is reported, “Reinforcements should have meant Colonel J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade, but that would take time since it was several miles away. Custer (newly promoted Gen. George A. Custer) was nearer but heading south to join Kilpatrick near the Round Tops. Therefore, General David McM. Gregg overrode Custer’s marching orders and sent him to help McIntosh take on the Rebels at Rummel’s farm. Custer, sensing this was where the action was, did not protest.”

And that, “A little after 3 p.m., the Federals noticed sunlight reflecting off something in the distance along Cress Ridge. It shone from the drawn sabers of (Wade) Hampton’s and (Fitzhugh) Lee’s brigades, massed in attack formation…Lieutenant William Brooke-Rawle of the 3rd Pennsylvania recalled, “In close columns of squadrons, advancing as if in review, with sabres (sic) drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight, the spectacle called forth a murmur of admiration. It was indeed a memorable one.”

Then, “As the gray riders advanced, Gregg personally ordered Colonel Charles Town to take his 1st Michigan out to meet them.” And, Town being quite ill, “…Custer rode up to lead them. The gait of both columns increased as they drew nearer, first at a trot then a gallop.”

When, “The front rank of the 1st Michigan wavered for a moment, then Custer yelled, “Come on you Wolverines!” and the entire regiment spurred ahead.”

Gregg’s troops, and in particular Custer’s Wolverines, were outnumbered by General J.E.B. Stuart’s charging legions, and, “Although the Wolverines numbered less than 500 against more than six times that many, their wedge-like penetration parted Hampton’s formation.”

Fortunately, help was close at hand, “While the 1st Michigan slugged it out with Hampton, who by now was supported on the flanks by Lee and (John R.) Chambliss, additional bodies of Federals that had been scattered about the field rallied and struck the Confederates on the flanks. Among them were two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania, under Captain Charles Treichel and Lieutenant William Rogers (should be Captain), who struck the Confederate right. Even Colonel McIntosh and about 20 officers and men from his headquarters group charged in to assist Treichel and Rogers.”

With the support of squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania also coming in from the Confederate left flank, the charge of Stuart’s brigades was turned back, in spite of the fact that, “Stuart had over 6000 men, a large proportion of them which he committed to the fight. Gregg had about 5000 men but only about 3000 saw action.”

Captain Rogers returned to service with the 3rd PA Cavalry following his recovery from his wounds September 28, 1863. February 6, 1864 he was appointed a Captain in the Veterans Reserve Corps serving in Washington, D.C. He was promoted for his gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Gettysburg, his highest brevet rank being Lt. Col. as of March 13, 1865.

Curt Harley, a cousin of this reporter, wrote in 2006 that Captain Rogers was an officer of the honor guard for President Lincoln both at his 2nd inauguration and while he lay in state. He also says: that Captain Rogers was in command of the cavalry detail at Ford Theater and was one of the first to notice that Lincoln was shot; that he was a good friend of Custer; and, that he was also a friend of Buffalo Bill Cody. Captain Rogers, in his own report of his service of 1883, writes that he served in Washington, D.C. during 1864 and until 1867, including in the Office of the Military Governor of Washington, D.C.

He continued in the Army for the rest of his career, 1867 until 1869 in Tennessee in charge of troops during the Reconstruction Era with the 45th Infantry and the 14th Infantry respectively, and then in April, 1870 at Crow Creek Agency, Dakota as Acting Assistant Quartermaster and A.C.S. (Acting or Assistant Chief of Staff) and subsequently commanding Company B, 14th Infantry.

Now Regular Army First Lieutenant Rogers’ personally written “Record of Service” records that “5/22/1871 On duty with Company G. 9th Inf. 1st Lieut. A.C.S. Fort D.A. Russell Wyo.” The formal certificate of his appointment as an officer in the Regular Army, of which I have a copy from Rogers Harley, reads “…William W. Rogers, I have nominated, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, do appoint him First Lieutenant in the Ninth Regiment of Infantry in the service of the United States: to rank as such from the twenty second day of May eighteen hundred and seventy one,…” and is signed by the Secretary of War and President U.S. Grant. Over the next sixteen years Captain Rogers and his family served with the Ninth Infantry on posts in Nebraska and Wyoming- the overall command being called the Department of the Platt.

First Lieutenant Rogers was married- his first wife’s name was Elizabeth (Lizzie). They had a daughter Florence (Floe) while serving in Tennessee, and apparently an older son Horace Byron. Floe died young at Fort D.A. Russell, Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory on July 21, 1871. Floe was first buried there “where the prairie winds will sweep over her grave” (a quote of First Lieutenant Rogers included in a letter of Rogers Harley in January 15, 1992 to my mother Dorothy Nesbitt). Lieutenant Rogers’ wife Lizzie died April 30, 1874, also at Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, and was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery, Omaha, Nebraska. In 1875 Floe was reburied beside her mother. Between these two tragic Cheyenne tours Lieutenant Rogers served at Sidney Barracks in southwest Nebraska. His son Horace it would also seem died rather young.From “Nov. 28, 1875 to Sept. 12, 1876” Lieutenant Rogers writes in his personal “Record of Service” of September 24, 1883 that he was “Commanding Camp Sheridan, Neb., and Company F. 9th Infantry.” This conforms to the History of the Ninth Infantry: 1799-1909, by Capt. Fred R. Brown, Adjutant, Ninth Infantry (1909), page 116 where it is recorded as follows:

“Company F left post (i.e. Camp Sheridan, Neb.) on May 8th, under command of First-Lieutenant W. W. Rogers, Ninth Infantry, to scout the country between the post and Custer City, with Company K. Second Cavalry. The company returned from Custer City via Camp Robinson, Nebraska, on the 29th of May. Distance marched, 418 miles.”

On a driving trip to visit western U.S. National Parks, including in the Black Hills and the Little Bighorn Battlefield, my wife and I recently visited those locations where Lieutenant, and later, Captain Rogers served in the Department of the Platt in the 1870s and 80s where there are still structures and such to visit. The Camp Sheridan site lies east of Chadron and north of Hay Springs in Nebraska, and south of Oglala which is due north in South Dakota, but nothing remains of the camp to visit. We followed Nebraska Route 20, the Crazy Horse Memorial Highway, east from Fort Robinson turning onto Highway 385 north, the Gold Rush Highway, heading for Custer City, South Dakota just before reaching Chadron. For more background, the role of Camp Sheridan and its relationship to Fort Robinson in the 1870’s is described below:

CAMP SHERIDAN AND SPOTTED TAIL AGENCY

About ten miles north are the sites of Spotted Tail Agency and Camp Sheridan. Named for Brule Sioux Chief Spotted Tail, the agency was built in 1874 to supply treaty payments, including food, clothing, weapons, and utensils, under the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. The army established Camp Sheridan nearby to protect the agency. A similar arrangement prevailed for the Ogalala Sioux at Red Cloud Agency and Camp Robinson forty miles west.

Spotted Tail Agency was generally quiet and peaceful throughout the Indian War of 1876-77. Crazy Horse surrendered there on September 4, 1877, after fleeing Red Cloud Agency. He was stabbed to death the next evening while being imprisoned at Camp Robinson, but his parents returned his body to Camp Sheridan for burial.

On October 29, 1877, Spotted Tail’s Brules were moved to present South Dakota. In 1878 they occupied the Rosebud Agency, where they live today. Camp Sheridan, with a peak garrison of seven companies of soldiers, was abandoned on May 1, 1881.

I had been wondering why Lieutenant Rogers’ “…scout (of) the country between the post (Camp Sheridan) and Custer City…” of May, 1876 received such specific attention in the History of the Ninth Infantry: 1799-1909, by Capt. Fred R. Brown (1909) supra. It is not the case for that work to give a routine “scout” such detailed attention. At the same time I was just finishing Thom Hatch’s recently published, early in 2015 by St. Martins Press, The Last Days of George Armstrong Custer, subtitle “The True Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.” When I connected the dots so to speak as I was finalizing this manuscript, I realized that Lieutenant Rogers, Co. F of the 9th Infantry and Company K, 2nd U.S. Cavalry weren’t just on a routine “scout”, but were undertaking what we would term today a Reconnaissance in Force. The reason, to be sure that the territory south of the Black Hills was secure from “hostile Indians” as the three prong approach into southeastern Montana of U.S. forces got underway in May of that year. This involved General Crook moving up the Rosebud Creek from northeast Wyoming, General Terry and Lt. Col. Custer coming from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory and moving due west and Colonel Gibbons coming from Fort Ellis to the west in Montana along the Yellowstone River. The objective, to find and destroy “hostile Indians” who would not peacefully return to their assigned reservations, and ultimately to converge on the confluence of the Rosebud and the Yellowstone in Montana. This was an opening phase of the Indian War of 1876-1877. General Crook would fight the Battle of the Rosebud and turn back. Lt. Col. Custer and five companies, of his men of the 7th Cavalry, Companies C, E, F, I and L, would go on to lose their lives in the Battle of the Little Bighorn of that June 25, 1876. For most in the Army and of the country, the death of Custer and his men at the Little Bighorn came as a shock, and logically this would have been even more so for Lieutenant Rogers. The man of then modern legend who he had fought in support of at Gettysburg on that hot and pivotal July day in 1863, who by family tradition he considered a good friend as they crossed paths “out west on the great plains” in the early years of the 1870s, and, as has been pass down in our family, had discussed going into business ventures together when they eventually retired from the service was not only defeated, but was killed. It had to be one of the great shocks of his life, though not on a par with the loss of his little Floe and two years later his wife Elizabeth.

But change was coming for Lieutenant Rogers and his command. By his own record, he was less than three months from returning east. By “September 12, 1876” he was “On duty at Fort Lavaunio (hand corrected to Fort Laramie), Wyo., Comd’y. Co., F. 9th Inf.”

While it seems rather a fast trip, Lieutenant Rogers and Helen King Dewey, a relative of Admiral Dewey, were married on September 19, 1876 at Unity Church, Chicago by the Reverend Robert Collyer. Interestingly, General L. P. Bradley who married one of Helen’s three sisters had been Lieutenant Colonel of the 9th Infantry Regiment (source: manuscript Pvt, Dewey Rogers 1881-1900: Co. “G”-9th Infantry U.S. Army by Rogers S. Harley (1991)). The newlyweds then went on to New York and other locations in the east where Lieutenant Rogers’ duties focused on recruiting for the Ninth Infantry.

Lieutenant Rogers and Helen then went west again, where he continued with the 9th Infantry, with which he would remain. As of “Dec. 16, 1878” he was “En-route to join Company F. 9th Infantry at Fort McKinney, Wyo.”, west of Buffalo, WY. By “March 31, 1880” he was “On duty at Fort Sidney, Neb., as Capt. Co., B. 9th Infantry.” Until “April 22, 1880” when he was “Enroute with Company B. 9th Infantry from Fort Sidney, Neb. to Fort Niobrara Neb., engaged in building the New post.” Helen and Captain Rogers’ only child, Dewey, was born July 22, 1881 at Ft. Niobrara, Nebraska where they served through April 13, 1883. By “Aug. 17, 1883” Captain Rogers and his family were at Fort Bridger, where he further writes in his personal “Record of Service”: “With Company engaged in repairing wagon road from Fort Bridger, Wyo., to Fort Thoruburg (sic, should be Thornburg)), Utah.” Regarding Fort Thornburg, During the summer of 1881 the military troops were established in Ashley Canyon for protection against Indians. Moving to Fort Thornburgh in December, 1881. The fort was abandoned in 1884 and part of the supplies taken to Fort Bridger”. (source: on-line copy of marker for Fort Thornburg).

In 1886 the 9th Infantry was reassigned to the Department of Arizona. This was very much hardship duty given the sever conditions of the climate and terrain. In 1887, for whatever reason, Captain Rogers requests and receives written official confirmation that he was wounded twice in action on July 3, 1863 (of which the family has a copy). Question: Was his health already declining and he was looking ahead to retiring for medical reason, and/or possibly the memories of the young of the day about the Battle of Gettysburg and his service a quarter of a century on needed such written documentation? Today we would say that he was at the least entitled to the Purple Heart medal. He retired from the service because of severe illness in 1889, and he, Helen and Dewey settled in Chicago. Due to his illness, Captain Rogers went to California hoping it would be helpful to his health. He died there in San Diego, December 14, 1890. In Brown, Supra, page 145, it is reported that “As indicating the severity of service, discomforts , and exhausting climate conditions in Arizona from 1886 to 1891, the regiment lost: Five Captains by retirement for disability, (one of whom died soon after): Two Captains by death, and one First Lieutenant by retirement for disability:…” and the list goes on. It would seem quite probable that the Captain who died soon thereafter is a reference to the death of Captain Rogers.

Following his wishes, Helen took Captain Rogers remains to Omaha, Nebraska, where he was buried in the Prospect Hill (Old) Cemetery, Lot 746, E1/2, beside his first wife, Elizabeth, and their young daughter, Floe. Helen would go on to Tacoma, WA where she had close relatives. Dewey Rogers would graduate from high school with Honors in Tacoma in 1898. Not being happy with office work, his mother had at first objected, but finally gave Dewey permission to join the Army. “His ultimate dream was to earn a commission in the 9th Infantry…He could not, however, because of quotas and the political prestige required, gain a place at West Point.” Dewey joined the army in Portland January 10, 1900, with the goal of becoming an officer in the 9th Infantry. He was posted to San Francisco, and February 17, 1900 was shipped out to the Philippines where he joined Company “G” of the 9th Infantry. On June 27, 1900 the 9th Infantry sailed from Manila for China to join the International Force fighting the Chinese Boxers. Tragically, Dewey died July 13, 1900 in China storming the walls of Tien Tsin during the Boxer Rebellion. In 1901 he was buried in the Tacoma (Washington) Cemetery, Section 2, Sub-section “E”, Lot #2. The source of this information after Captain Rogers’ death comes from the manuscript, Pvt. Dewey Rogers, 1881-1900, Company “G”- 9th Infantry U.S. Army, by Rogers S. Harley (1991).Thanks to Captain Nesbitt for his contribution, and thanks also to him for providing the images that appear here.

Here’s to Bvt. Lt. Col. William Wallace Rogers, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Comments

Comments are closed.