Part 1 of a series. Cross-posted at Emerging Civil War:

The stakes were high. Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s 5,500 man corps was in a race for its life. If it could reach the Clarendon Bridge across the Cape Fear River in Fayetteville, NC first, Hardee could get his men across and then destroy the only crossing of the Cape Fear in the area. The Cape Fear is navigable as far north as Fayetteville, so it could only be crossed by bridge or ferry in the Fayetteville area. If Hardee could destroy the bridge, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 65,000-man army would have to halt and wait for bridging materials to be brought up river from Wilmington. By the time that the bridging materials arrived and Sherman got his army across the Cape Fear, Hardee would be well on his way to joining the force that Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who came out of retirement to assume command of the remaining Confederate forces in North Carolina in February 1865, was assembling near Smithfield.

Leading Sherman’s pursuit was the Third Cavalry Division, commanded by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick’s division—consisting of three brigades of mounted men and an ad hoc brigade of those men who had lost their horses and had not been able to replace them—was the only cavalry with Sherman’s grand army. Kilpatrick, of questionable reliability, had already demonstrated that his command could be caught by surprise at Aiken, South Carolina on February 11, was the weak link in Sherman’s army. However, in the absence of any alternatives, Kilpatrick and his troopers would have to do.

Leading Sherman’s pursuit was the Third Cavalry Division, commanded by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick’s division—consisting of three brigades of mounted men and an ad hoc brigade of those men who had lost their horses and had not been able to replace them—was the only cavalry with Sherman’s grand army. Kilpatrick, of questionable reliability, had already demonstrated that his command could be caught by surprise at Aiken, South Carolina on February 11, was the weak link in Sherman’s army. However, in the absence of any alternatives, Kilpatrick and his troopers would have to do.

Closely shadowing Kilpatrick’s pursuit of Hardee’s infantry was a large and still effective force of Confederate cavalry. Even at that late date, the Confederates could still put more than 5,000 horsemen in the field, consisting of f about 4,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, whose command had been shadowing Sherman’s army since the beginning of the March to the Sea, and another 1,200 or so troopers from the Army of Northern Virginia under command of the newly-promoted Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton who had been sent to South Carolina at Hampton’s request in February to help defend against Sherman’s army. As the highest-ranking officer in the Confederate cavalry service, Hampton had overall command of this large force of Southern horsemen.

Closely shadowing Kilpatrick’s pursuit of Hardee’s infantry was a large and still effective force of Confederate cavalry. Even at that late date, the Confederates could still put more than 5,000 horsemen in the field, consisting of f about 4,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, whose command had been shadowing Sherman’s army since the beginning of the March to the Sea, and another 1,200 or so troopers from the Army of Northern Virginia under command of the newly-promoted Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton who had been sent to South Carolina at Hampton’s request in February to help defend against Sherman’s army. As the highest-ranking officer in the Confederate cavalry service, Hampton had overall command of this large force of Southern horsemen.

By the afternoon of March 9, 1865, Kilpatrick’s command was only a few miles behind Hardee’s infantry. Each of Kilpatrick’s three brigades of mounted men used a different road to pursue the Confederates. Kilpatrick himself rode with the brigade of Col. George E. Spencer, which was accompanied by Lt. Ebenezer Stetson’s two-gun section of the 10th Wisconsin Battery, and the dismounted troopers, organized into ad hoc regiments based on which brigade they served in, all under command of Lt. Col. William B. Way of the 9th Michigan Cavalry. Nightfall came quickly on the short early March days, and Kilpatrick decided to halt at the intersection of the Morganton and Blue’s Rosin Road, not far from Fayetteville. Kilpatrick established his headquarters in the Monroe farmhouse, where he spent the night in the company of an unidentified woman who was traveling with his command and who was considered to be a woman of loose morals. That intersection, known as Monroe’s Crossroads, would become the site of the last large cavalry battle in the Western Theater of the Civil War the next day.

By the afternoon of March 9, 1865, Kilpatrick’s command was only a few miles behind Hardee’s infantry. Each of Kilpatrick’s three brigades of mounted men used a different road to pursue the Confederates. Kilpatrick himself rode with the brigade of Col. George E. Spencer, which was accompanied by Lt. Ebenezer Stetson’s two-gun section of the 10th Wisconsin Battery, and the dismounted troopers, organized into ad hoc regiments based on which brigade they served in, all under command of Lt. Col. William B. Way of the 9th Michigan Cavalry. Nightfall came quickly on the short early March days, and Kilpatrick decided to halt at the intersection of the Morganton and Blue’s Rosin Road, not far from Fayetteville. Kilpatrick established his headquarters in the Monroe farmhouse, where he spent the night in the company of an unidentified woman who was traveling with his command and who was considered to be a woman of loose morals. That intersection, known as Monroe’s Crossroads, would become the site of the last large cavalry battle in the Western Theater of the Civil War the next day.

Kilpatrick was careless and sloppy in his dispositions. He had only a single company of the 5th Kentucky Cavalry of Spencer’s brigade deployed as pickets on the Morganton Road. Wheeler’s lead elements—scouts of the 8th Texas Cavalry (Terry’s Texas Rangers) under command of Capt. Alexander Shannon—caught the Kentuckians by surprise and captured them en masse, meaning that Kilpatrick had no other early warning system in place in case the Confederates approached. This was incredibly negligent and violated nearly every rule for cavalry in the field, and it nearly cost Kilpatrick dearly.

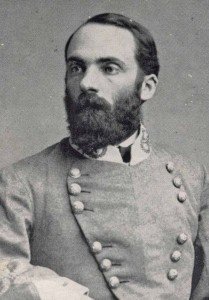

Wheeler and Hampton recognized that Kilpatrick’s entire command was vulnerable. Hampton developed a plan whereby his entire command would pounce on Kilpatrick’s vulnerable camp. Wheeler, with his entire corps, would attack at dawn from the west, while Maj. Gen. Matthew C. Butler, commanding Hampton’s old division, would attack from the north with Col. Gilbert Wright’s brigade (Hampton’s old brigade), while the brigade of Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law would be held in reserve. It was a brilliant plan, and if it was executed properly at dawn as ordered, the grayclad horsemen would fall upon the sleeping Union camp like a tidal wave.

Wheeler and Hampton recognized that Kilpatrick’s entire command was vulnerable. Hampton developed a plan whereby his entire command would pounce on Kilpatrick’s vulnerable camp. Wheeler, with his entire corps, would attack at dawn from the west, while Maj. Gen. Matthew C. Butler, commanding Hampton’s old division, would attack from the north with Col. Gilbert Wright’s brigade (Hampton’s old brigade), while the brigade of Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law would be held in reserve. It was a brilliant plan, and if it was executed properly at dawn as ordered, the grayclad horsemen would fall upon the sleeping Union camp like a tidal wave.

However, as the old cliché about the best-laid plans of mice and men goes, while the plan was brilliant, its execution left something to be desired.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Excellent article and book, Eric!

The following paragraph is from Wiley Chandler Howard’s Sketch of Cobb Legion Cavalry and Some Incidents and Scenes Remembered.

Lt. Col. Barrington S. King was in command (of the Cobb’s Legion cavalry), Col. Gib Wright commanding the brigade. At half past two o’clock in the morning, that fearless and peerless soldier, Lieut. Tom Donahoo (Dunnahoo), with Gen. M. C. Butler, personally captured the vidette and with others surprised and took the whole picket force on the road by which we approached, without the firing of a gun or making any disturbance, and we waited in column until the early dawn, when we fell upon the camp like a small avalanche, riding pell-mell over the enemy, asleep many of them, while others were preparing their coffee and breakfast.

Lt. Dunnahoo was my great-great grandfather. I know for sure he had fought against Gen. Kilpatrick’s troops at Brandy Station and Trevilian Station, VA and also possibly at Hunterstown, PA. He survived the battle at Monroe’s Crossroads and also Bentonville, but he would later be killed during the action at Swift Creek (about ten miles south of Raleigh) on April 12, 1865. He is buried in the Confederate soldier section of Oakwood Cemetery in downtown Raleigh.