Author:

Here is another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten Civil War cavalrymen. Today’s profile is of a particular favorite of mine.

Here is another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten Civil War cavalrymen. Today’s profile is of a particular favorite of mine.

Nineteenth Century American cavalrymen were the fighter pilots of their era—devil-may-care, flashy, equally eager to impress the women and eager to seek glory for dashing deeds of courage. When modern students of the Civil War think of cavalrymen, they conjure up images of Jeb Stuart, with his ostentatious ostrich plumes, or of George Custer and his flowing blonde hair and outrageous uniforms. Certainly, the cavalry produced more than its fair share of cads like Earl Van Dorn and Judson Kilpatrick.

However, it also produced some extraordinary soldiers—quiet, modest, competent men who went about their business in an efficient, professional way. This category includes men like John Buford, David Gregg, Wesley Merritt, and Thomas C. Devin on the Northern side, and Wade Hampton, Matthew C. Butler, Lunsford L. Lomax, and Thomas T. Munford on the Southern side. More interested in doing their jobs well than in reaping favorable press clippings, these men avoided the harsh spectacle of the press’s prying eyes.

Theophilus F. Rodenbough fell into the latter category. In fact, it’s quite likely that only a handful of readers of this blog have ever heard of Rodenbough. He probably would have wanted it that way. Nevertheless, his story has languished in obscurity for more than a century, and the time has come to pay tribute to a brave man who was a fine soldier who sacrificed his health in the service of his country. Instead of allowing that to destroy his life, Rodenbough used his post-Army career to become one of the most gifted and prolific military historians of the Nineteenth Century.

The son of Charles and Emily Rodenbough, Theophilus Francis Rodenbough was born in Easton, Pennsylvania on November 15, 1838. The boy’s father owned a rolling mill and wire factory where the first telegraph wire was made. He had one brother, Joseph K. S. Rodenbough, who was also a successful businessman in Easton after the Civil War. His father was active in the Presbyterian church, and served on a number of boards of trustees, including that of a local bank.

Theophilus, a child of privilege, attended private schools, had special tutors, and enrolled in a course of mathematics and English literature at Easton’s Lafayette College in 1856 and 1857. He left Lafayette after a year of studies and tried his hand at business, a field for which he was not well suited. The young man seemed adrift, searching for his life’s calling. As the storm clouds of war gathered on the horizon in 1860, the young man realized that he might enjoy a soldier’s life, and he set about pursuing his new dream.

Rodenbough enlisted the assistance of Representative Andrew H. Reeder, his Congressman, and began his campaign to obtain an officer’s commission. On March 27, 1861, a scant two weeks before the first shots at Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln signed a second lieutenant’s commission for Rodenbough. Rodenbough would join the 2nd U. S. Dragoons, a legendary unit that produced the likes of John Buford and Wesley Merritt. Not long after the outbreak of the Civil War, the Regular Army’s mounted units were reorganized and the 2nd Dragoons received a new designation, the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Now that he wore a second lieutenant’s shoulder straps, Theo Rodenbough had to learn his chosen trade. Unlike today, where new officers have the benefit of attending Officer Candidate School, there was no such luxury in 1861.

To learn how to be a soldier, Rodenbough reported to the Cavalry School of Practice at the Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. There, he underwent intensive training and learned his new trade. The bright young man quickly demonstrated administrative abilities and became post adjutant and quartermaster for the Cavalry School, serving in that role during the first year of the Civil War. As a reward for his good service, he was promoted to first lieutenant later in 1861. By the time he reached his first anniversary in the United States Army, the young officer had mastered the skills needed to command horse soldiers in the field, and he joined his regiment in time to participate in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

On July 17, 1862, just fifteen months after joining the army, Rodenbough received a second promotion, this time to captain. By way of comparison, John Buford, considered by many to be the finest cavalryman of the American Civil War, did not receive his captain’s bars until he had served in the army for eleven years. Of course, the coming of war provided ample opportunities for a capable officer to advance his career, and Rodenbough benefited by it. Rodenbough served with his regiment throughout 1862, and was captured at the Battle of Second Bull Run on August 30, 1862. He was exchanged a week later and rejoined his regiment just in time for the 1862 Maryland Campaign. In October 1862, he went on recruiting duty, raising a new company of Regulars, Co. L, of which he assumed command.

During the spring of 1863, he led a squadron on the Stoneman Raid in April-May, 1863. He commanded a squadron at the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, where he was slightly wounded and had two horses shot out from under him. On June 28, 1863, Capt. Wesley Merritt, commander of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, received a commission as brigadier general of volunteers and assumed command of the Army of the Potomac’s Reserve Brigade. Rodenbough, the regiment’s senior captain, took command of the 2nd U.S., just two scant years after joining the army. His rise through the ranks of the Regular Army, notorious for slow promotions, was meteoric.

He commanded the 2nd U.S. at Gettysburg and during the retreat, as well as during the fall fighting in 1863. Rodenbough had two more horses shot out from under him during the course of the Gettysburg Campaign. In the spring of 1864, with Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan in command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, the Union horse soldiers expected a busy campaigning season. They were not disappointed. Rodenbough led his regiment at the Battle of Todd’s Tavern on May 7, 1864, at Yellow Tavern on May 11, and during the Richmond Raid of May 1864.

During the opening moments of the Battle of Trevilian Station, on June 11, 1864, Rodenbough received a serious wound when shot at point blank range in the left shoulder by a South Carolina cavalryman. Following Merrit’s instructions, Rodenbough led the advance of the Regulars himself, riding alone and in front of the rest of the Reserve Brigade. As he turned to give orders, a South Carolinian of Brig. Gen. Matthew C. Butler’s Brigade shot him. Rodenbough turned over command of the regiment to his senior captain and retired, desperately wounded.

Merritt praised his subordinate. “Had Rodenbough simply detached the squadron, transmitted the orders through his adjutant and remained with his regiment he would have executed my order in the customary way. As it was I judged his action then as I have since regarded it as especially distinguished and of great benefit, as an example of valor, as well as leading quickly to an important result.” Sheridan urged Rodenbough’s promotion as a result of his valor on June 11. Thirty years later, Merritt submitted Rodenbough’s name for a Medal of Honor, over Rodenbough’s objections, writing, “I know of no living officer more surely entitled to the honor than he.” In 1894, Rodenbough received the Medal of Honor “for distinguished gallantry in action at Trevilian Station while handling his regiment with great skill and unexampled valor.” Rodenbough responded, “I value this distinction especially because it comes to me at the instance of my former commander, Gen. Merritt.”

Rodenbough went on sick leave and recruiting duty before rejoining his regiment in September 1864, just in time for the Third Battle of Winchester. There, in the great mounted charge of five brigades at Fort Collier, on September 19, 1864, with Rodenbough leading his Regulars forward, he received another severe wound, this time costing him his right arm, which was amputated three inches below the shoulder. “At the battle of the Opequon, he displayed almost unparalleled gallantry and coolness,” observed Maj. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert, commander of the Army of the Shenandoah’s Cavalry Corps, “finally, near Winchester while charging at the head of his regiment in a brigade against the enemy’s infantry, he received a wound which cost him his right arm.”

In recognition of his valor at Winchester, he was brevetted major “for gallant and meritorious service.” The severely wounded captain spent three weeks convalescing in the Winchester home of a staunch Unionist before going home to Easton for another three weeks. He then did recruiting duty in Philadelphia from November 1864-April 1865. He received a brevet to lieutenant colonel “for gallant and meritorious conduct during the war” on March 19, 1865.

During the winter of 1864-65, Sheridan and Torbert mounted a campaign to obtain a colonel’s commission for Rodenbough so that he could take over the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry. “He is a gallant and meritorious young officer,” wrote Sheridan, “and would do honor to the grade asked for him.” Torbert echoed a similar note: “He is one of the most deserving young officers of the cavalry, and will not disappoint any trust reposed to him.” With such distinguished support for his promotion, Rodenbough received a commission as colonel of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry on April 29, 1865, and the thrice wounded officer served in the Middle Military Division, commanding the Brigade District of Cumberland, Maryland and the Sub-District of Clarksburg, West Virginia from June until November 1865.

Just four years and four months after joining the army, in July 1865, he received a brevet to brigadier general, U.S. volunteers, “for gallant and distinguished conduct during the war,” and also received an assignment to duty at that rank from President Andrew Johnson. Dated March 13, 1865, he also received a brevet to colonel in the U. S. Army “for gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Todd’s Tavern,” May 7, 1864 and to brigadier general, U. S. Army “for gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Cold Harbor.”

In recommending Rodenbough for his final brevet, Sheridan wrote, “Colonel Rodenbough was one of my most gallant and valuable young officers, under my command, in the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. He was constantly in the field with his regiment, the 2nd U. S. Cavalry (a portion of the time in command of it), from the spring of ’62 up to the time of his being wounded whilst gallantly leading his regiment at the Battle of Opequon, September 19, 1864.”

On October 31, 1865, he mustered out of the volunteer service and returned to 2nd U. S. Cavalry. In the winter of 1865-66, he joined the staff of Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge as Acting Assistant Inspector General, a position he held until May 1866. “An educated soldier of strict integrity and excellent morals, his ability and past services entitle him to promotion,” urged Dodge in a letter to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in 1866. Rodenbough served at various posts in Kansas in 1866, and then received an appointment as major of the 42nd U. S. Infantry on July 28, 1866. He served with the regiment at Hart Island, New York and in various staff positions until May 1867, when he assumed command of the Plattsburgh Barracks in New York until the end of the year.

He then commanded the regiment and post of Madison Barracks in Sackett’s Harbor, New York from December 1867 to April 1869. “On the eve of your departure from this command I avail myself of the opportunity to express my thanks for the efficient manner in which you discharged your duties while serving under me in the Department of the East,” proclaimed Maj. Gen. George G. Meade in the spring of 1869, “both as regimental commander and in charge of the military station at Sackett’s Harbor. Your official course has met my approval, and I feel confident that to whatever position you are assigned you will display the same zeal and efficiency which characterized your conduct here.”

Rodenbough went on recruiting duty in Cincinnati and Detroit for a time. In December 1870, he appeared before a Retiring Board commanded by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. After hearing testimony from surgeons and from Rodenbough himself, the panel concluded that the cavalryman was “incapacitated for active service, and that said incapacity is due to the loss of his right arm, about three inches below the shoulder joint, in consequence of a wound received at the Battle of Winchester, September 19, 1864.” He was retired “with full rank of Colonel of Cavalry, on account of wounds received in the line of duty.” He was just thirty-two years old.

The gallant young colonel had married Elinor Frances Foster at the Church of the Incarnation in New York City on September 1, 1868. Their forty-four year marriage was fruitful, producing two daughters and a son, although their first child, Mary McCullagh Rodenbough only lived two years. After retiring from the Army, he remained active and productive. He served as Deputy Governor of the U. S. Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D. C. in 1870-1871, and the accepted an appointment as General Eastern Agent, Pullman Car Company for two years. He served a two-year term as Associate Editor of the Army and Navy Journal in 1876-77, and became Secretary and Editor of the Journal in 1878, a post he held for twelve years. From 1891-1893, he served as Vice President of the Military Service Institution of the United States, and as Chief of the Bureau of Elections, City of New York, 1890-1892.

The gallant young colonel had married Elinor Frances Foster at the Church of the Incarnation in New York City on September 1, 1868. Their forty-four year marriage was fruitful, producing two daughters and a son, although their first child, Mary McCullagh Rodenbough only lived two years. After retiring from the Army, he remained active and productive. He served as Deputy Governor of the U. S. Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D. C. in 1870-1871, and the accepted an appointment as General Eastern Agent, Pullman Car Company for two years. He served a two-year term as Associate Editor of the Army and Navy Journal in 1876-77, and became Secretary and Editor of the Journal in 1878, a post he held for twelve years. From 1891-1893, he served as Vice President of the Military Service Institution of the United States, and as Chief of the Bureau of Elections, City of New York, 1890-1892.

With the coming of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the sixty-year old warrior tried to obtain a commission and take the field again, writing, “Here is an old sword-blade not so rusty that it will take a respectable polish yet; and I imagine there are several others on the Retired List.” He actively campaigned for an administrative position in the army, but his age and disabilities produced a gentle rebuff. He tried again in 1904, now sixty-four years old, writing, “I have the honor to apply for assignment to duty and detail on recruiting or other service, preferably with station in [New York City].” Rebuffed again, due to an act of Congress, Rodenbough was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, retired, in May 1904, meaning that the honorific of “general” became real, and not just by brevet.

Filling his retirement years, General Rodenbough proved to be a prolific writer and gifted historian. In addition to a comprehensive family genealogy, he wrote numerous articles on diverse topics such as Sheridan’s May 1864 Richmond Raid, the Trevilian Raid, lessons learned by the cavalry in the Civil War, and others. He authored a superb history of his former regiment titled From Everglade to Canon with the Second Dragoons (1875) as well as a history of the Anglo-Russian dispute over Afghanistan (1882). He also wrote The Bravest Five Hundred of 1861, providing thumbnail sketches of various Medal of Honor winners, and a companion volume, Uncle Sam’s Medal of Honor, as well as co-authoring a history of the United States Army. He edited the cavalry volume of Francis Trevelyan Miller’s Photographic History of the Civil War, and headed the committee given the task of preparing a regimental history for the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

After a long and productive life, Theophilus F. Rodenbough died at his home in New York City on December 19, 1912. His wife, who joined him in death a few years later, survived him. He was buried with full military honors in the family plot in Easton Cemetery in his hometown. He was seventy-four years old, and he had packed a great deal of living into those years.

After a long and productive life, Theophilus F. Rodenbough died at his home in New York City on December 19, 1912. His wife, who joined him in death a few years later, survived him. He was buried with full military honors in the family plot in Easton Cemetery in his hometown. He was seventy-four years old, and he had packed a great deal of living into those years.

In nine years and eight months in the Regular Army, this dashing horse soldier earned five promotions, two brevets in the volunteer service, and four brevets in the Regular service. Along the way, he impressed almost every officer he served under. “General Rodenbough is a cultivated and refined gentleman of ability and integrity,” wrote Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, summing him up nicely, “and is well and favorably considered wherever known. His record as an officer during the war was irreproachable, and he was disabled for life by the loss of an arm while gallantly performing his duty in battle.”

His rise had been meteoric, and only his battle wounds terminated a promising military career that probably would have led to high command. But for those wounds, Rodenbough likely would be remembered as one of the greatest horse soldiers in American history. Thus ended the fascinating life of a gifted soldier and scholar, a man who spent his life in the service of the Army that he loved, and in doing the duty that marked his character.

Here’s to Theo Rodenbough, forgotten cavalryman, Medal of Honor recipient, and cavalry historian. He was one of those natural soldiers who rose to prominence despite a lack of any formal military training.

Scridb filter Today marks the Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, fought March 17, 1863, along the banks of the Rappahannock River in Culpeper County, Virginia. Please click on the image to see a larger version of this contemporary depiction of the fighting at Kelly’s Ford that St. Patrick’s Day.

Today marks the Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, fought March 17, 1863, along the banks of the Rappahannock River in Culpeper County, Virginia. Please click on the image to see a larger version of this contemporary depiction of the fighting at Kelly’s Ford that St. Patrick’s Day.

That day, Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell’s Second Cavalry Division of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac forced its way across the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and brought the Confederate cavalry brigade of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to battle. The fight lasted for most of the day. First, Averell’s men had to force a crossing of the river, pushing through Confederate rifle pits. They then had to force their way through felled trees that blocked the road. Once they Union horse soldiers forced their way across the river and through the abatis, Averell then ordered his men to charge. Mounted charges met by mounted countercharges by Fitz Lee’s horsemen went back and forth for much of the afternoon. Maj. John Pelham, Jeb Stuart’s gifted chief of horse artillery, foolishly joined a charge by the 5th Virginia Cavalry near the Wheatley farm, and received a mortal wound when a Union artillery shell burst on a stone wall, spraying deadly shrapnel. One of those pieces of shrapnel took Pelham’s life.

Daniel Davis has written a nice account of the battle that appears over at Emerging Civil War. I recommend it to you.

Averell pushed the Confederate horsemen back a mile or two, and then he paused to dress his lines. The final charges too place on the property just preserved by the Civil War Trust. Incorrectly believing that the Confederate cavalry had received infantry reinforcements, and with his force alone and behind enemy lines, Averell broke off and withdrew from the battlefield, leaving it in Fitz Lee’s hands. By all measures, Kelly’s Ford was a Confederate victory. Lee’s troopers held the battlefield at the end of the day, and Averell failed to accomplish his strategic goal, which was to disperse the Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County. However, that victory cost the Confederacy the services of John Pelham.

Averell pushed the Confederate horsemen back a mile or two, and then he paused to dress his lines. The final charges too place on the property just preserved by the Civil War Trust. Incorrectly believing that the Confederate cavalry had received infantry reinforcements, and with his force alone and behind enemy lines, Averell broke off and withdrew from the battlefield, leaving it in Fitz Lee’s hands. By all measures, Kelly’s Ford was a Confederate victory. Lee’s troopers held the battlefield at the end of the day, and Averell failed to accomplish his strategic goal, which was to disperse the Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County. However, that victory cost the Confederacy the services of John Pelham.

For a larger version of Steve Stanley’s excellent battle map (which shows the recently preserved battlefield land in yellow), please click on the map. As always, I am grateful to the Civil War Trust for allowing me to borrow its extremely useful interpretive maps.

My friend Craig Swain has a post on his blog today about the commemoration of the battle that took place today, including some photos of the battlefield as it appears today. It includes photos of the new pullover and new interpretive markers that have just been placed on the land preserved by the Civil War Trust. Please check them out.

There are some interesting quotes by participants in the Battle of Kelly’s Ford that provide insight into the fierce fighting there. “A cavalry charge is a terrible thing. Almost before you can think, the shock of horse against horse, the clash of steel against steel, crack of pistols, yells of some poor lost one, as he lost his seat and went down under those iron shod hoofs that knew no mercy, or the shriek of some horse overturned and cut to pieces by his own kind,” recalled Pvt. William Henry Ware of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry. “It is Hell while it lasts, but when man meets his fellow man, face to face, foot to foot, knee to knee, and looks him in the eye, the rich red blood flows through his veins like liquid lightning. There is blood in his eye, Hell in his heart, and he is a different man from what he is in the time of peace.” One of Averell’s men left a parallel description. “It was like the coming together of two mighty railroad trains at full speed. The yelling of men, the clashing of sabers, a few empty saddles, a few wounded and dying, and the charge is over. One side or the other is victorious, perhaps, only for a few minutes, and then the contest is renewed,” observed Sgt. George Reeve of the 6th Ohio Cavalry. “A charge of this kind is over almost before one has time to think of the danger he is in.”

Moreover, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford proved to be a real turning point in the evolution of the Union cavalry. For the first time, the Federal horsemen stood and fought the very best that the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Division had to offer, and the Federals gave as good as they got. Lt. Joseph A. Chedell of the 1st Rhode Island, wrote that Kelly’s Ford was the “first real, and perhaps the most brilliant, cavalry fight of the whole war.” From that moment forward, the Union horsemen believed that they were the equals of Stuart’s vaunted troopers, and from that moment forward, the blueclad horse soldiers went into battle with confidence and skill. Just three months later, those same troopers–no longer commanded by Averell–fought Stuart’s troopers to a standstill on nearby Fleetwood Hill during the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station.

That evolution–and its implications for the rest of the Civil War in the east–make this day of brutal combat worth commemorating. Today, we pay tribute to the brave men of both sides who crossed sabers during the Battle of Kelly’s Ford.

Scridb filter Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

We’ve long known that Carpenter–a very intelligent and literate man–left behind a large set of some of the best Civil War letters home to be found anywhere. They are located in his home town of Philadelphia at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The problem is that they are in bound volumes and HSP will not permit them to be photocopied. So, if a researcher wants to use them, they must be transcribed by hand, which is, to say the least, a great inconvenience. That’s why the letters have never been published as a set, even though they really deserve to be. He also published a number of good articles on cavalry service and a large family genealogy (Carpenter was directly descended from Samuel Carpenter, who was William Penn’s right-hand man, meaning he was a Philadelphia blue-blood). His brother, J. Edward Carpenter, served as a major in the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry–a Philadelphia regiment–and left behind one of the best contemporary accounts of what we now know as “Keenan’s Charge” on May 2, 1863 during the Battle of Chancellorsville. Both Carpenter brothers were good and prolific writers.

What we didn’t know is that the letters at HSP are only part of the collection of material he left behind. There are also diaries and a sketchbook of Carpenter’s observations during his time in the field during the Civil War. Bud Hall recently purchased this collection and found some amazing things therein. The most amazing find–and perhaps the most valuable of the images–is a sketch Carpenter drew in December 1863 of St. James Church–which sits in the middle of the Brandy Station battlefield, and was the site of the charges of the 6th Pennsylvania and 6th U.S. Cavalry during the morning phase of the the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. Carpenter drew the sketch just before the troopers of the 6th U.S. tore the church down to use the wood and pews for firewood and the bricks to build chimneys for their huts during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. This is the ONLY known contemporary image of the church, and it finally answers a question that those of us who study the Battle of Brandy Station have long wondered: What did St. James Church look like? Bud spent 25 years searching for a contemporary image of the little church and could never locate one. A 1989 archaeological survey of the church site told us what the footprint of the church looked like, and Bud speculated what it looked like, but nobody knew for sure. Thanks to Carpenter, we finally know the answer.

Below is a profile of St. James Church written by Bud Hall that gives the history of this otherwise obscure little church in the woods:

The Little Church that Would Not Die–St. James Episcopal: Rebirth of a Country Church

Richard Hoope Cunningham and his wife Virginia (Heth) arrived in Culpeper in 1833 and built a magnificent home, “Elkwood,” fronting the Rappahannock. Devout Christians, the Cunninghams routinely forded the river and attended services in Fauquier.

Weary of traversing a waterway that often proved dangerously swollen, the Cunninghams selected two acres about two miles back from the river as a suitable church site. Along with their neighbors, the Cunninghams then endowed the construction of a “first class country church.”

The two-story church—made of red brick fired on-site by slave labor—stood 40 by 40 feet, was “carpeted and nicely furnished, with cushioned pews.” Church officials were especially proud of its “big gallery all around for the colored people.” The total cost of construction materials was about $2000.

The beloved Rev. John Cole served as the first Rector of the new church in 1840, later consecrated in 1842 as St. James Episcopal Church. By 1860, the congregation boasted 28 communicants, with 40-50 black and white souls attending weekly services. A cemetery was laid out and all races were interred therein, with the same lovely periwinkle covering all beneath.

The little church proved so prosperous a parsonage loomed, and St James’s members donated $3000 to that end in 1861. But as events transpired, this munificent outlay soon reverted back as member families needed those funds for the next four years. War had come to Culpeper, and almost all of the county’s cherished churches were tallied as casualties during the ruinous conflict. And St. James was the first Culpeper house of worship to experience defilement, and then finally, total destruction.

Located near the wartime intersection of three roadways—Beverly’s Ford Road; Winchester Turnpike and Green’s Mill Road—St. James’s strategic placement near the river guaranteed the modest structure would suffer an inevitable concussive impact centered as it was between contending armies.

And by the thousands, Blue and Gray combatants tramped and fought about St. James. In 1862, pews were removed to enfold Rebel dead incurred in a fierce artillery duel. On June 9, 1863, fighting raged in front of St. James as Jeb Stuart’s legions beat back Federal charges during the Battle of Brandy Station. Several Rebel soldiers killed nearby sleep their final rest today in St. James’s burial ground.

Two Union soldiers in late 1863 left insightful glimpses of St. James: The first, an Illinois trooper, gazed upon the church and wrote his Chicago parents, “I admire the taste of Virginians in regard to building churches. They are not imposing structures and are always located in the woods.” A Pennsylvania officer described St. James as a “modest sanctuary…suggesting a time back when the woods were the first churches.”

Ironically, this latter soldier participated in taking St. James apart brick by brick in December 1863 to be used as chimney material during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac. Soon there was nothing left. Even the church bible was stolen. Robbed of their precious church, St. James members “worshipped God, like the primitive Christians, in private homes.”

But all wars finally do end, and in 1865, a new church was sought to replace St. James. We don’t know why the former site of St. James was not utilized; perhaps the reasoning suggested nothing more than the fact Brandy Station offered convenience for a post-war congregation. And then again maybe the bitterness over the loss of their lamented country church precluded a return to the “crime scene.”

“St James Church has risen from the ashes in the embodiment of Christ Episcopal Church at Brandy Station,” an exultant Rev. John Cole proclaimed in 1868.

In 1869, the new church was dedicated and consecrated “to supply the place of the building…entirely destroyed during the recent war.” Still offended at the wanton destruction of St James, Christ Church petitioned the Federal government for compensatory redress, and in 1914 the U.S. Court of Claims allowed the sum of $1,575 expended “as an equitable claim …that the United States received the benefit of the use of the material claimed for.”

Having fulfilled its duty by satisfying the honor of its ancestor church, the esteemed Christ Church congregation now also has St. James’s bible back in the fold—graciously returned by a former enemy. Christ Church continues today to hold in trust for the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia the St. James Church parcel, and the Brandy Station Foundation deferentially maintains, under lease, this beautiful, sacred church ground and its lonely cemetery.

Enter St. James today, if you will, and quietly and reverently experience the holy memory of a little church in the woods that refused to die.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

The image is very accurate: the graves are correctly shown, as is a defensive trench just beneath the gravestones, and if you visit the site today, you can still find the same small grouping of graves nestled among a grove of trees grown up since the war.

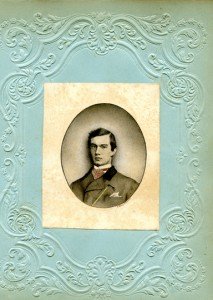

The self-portrait of Carpenter at the top of this post also comes from the sketchbook acquired by Bud. The same rules apply to it. I had looked for an image of him for years, but could only find one from late in his career, so I am very pleased to finally see a wartime image of him. You can see a larger image of it by clicking on it, too.

Bud has very generously agreed to permit me to use any of these images, and any of the other material that he now owns, in a future volume on Carpenter. I haven’t quite decided whether to edit the letters or to write a full-length biography of this fascinating soldier, but I will do something with them that makes good use of Bud’s collection of outstanding primary source material from Carpenter himself.

I’m tickled to be able to offer you the first look at these materials. Thanks to Bud Hall for permitting me to do so.

Scridb filterFor those interested in the upcoming Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford (fought on March 17, 1863), my friend and fellow BSF board member in exile Craig Swain is leading a commemoration of the battle next Sunday (St. Patrick’s Day), from 2:00-3:15. The commemoration will occur on the battlefield proper, at the time when the battle was taking place. The event is to both commemorate the battle, but also to dedicate a new interpretive spot on some of the ground preserved last year by the Civil War Trust.

Craig has further details on his blog. If you’re in the area, please check out this event!

Scridb filterTed Savas has a gift for getting his company’s books placed with the History Book Club, the Military Book Club, and Book of the Month Club 2. He has a terrific record of success with doing so; of my works, The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Final Campaign, and the second edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions: Farnsworth’s Charge, South Cavalry Field, and the Battle of Fairfield, July 3, 1863 were both featured selections.

Ted just informed me that the new edition of Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg: The Battles for Brinkerhoff’s Ridge and East Cavalry Field, July 2 – 3, 1863 has also been chosen by the book clubs. Ted informs me that it will be a featured alternate in the July 2013 catalog offering, which mails on June 2, 2013. I am, of course, very flattered to learn this, and am excited to be featured by the book clubs once more. For those of you who are members of any of the three book clubs, please keep an eye out for it.

Thanks again to Ted for making this happen.

Scridb filterThanks to Bruce Long for bringing his blog on the Civil War in northeast North Carolina to my attention, as I had missed it previously. Those of you who have followed this blog for a long time know of my fascination with the Civil War in the Tarheel State, which has long interested me a great deal. I’m glad to add this one to the blogroll.

Scridb filter This article appeared in the August 13, 1865 edition of the New York Times and is the earliest account of the fascinating story of how Ulric Dahlgren’s remains were secretly recovered and taken to a safe spot near Atlee’s Station, Virginia.

This article appeared in the August 13, 1865 edition of the New York Times and is the earliest account of the fascinating story of how Ulric Dahlgren’s remains were secretly recovered and taken to a safe spot near Atlee’s Station, Virginia.

COL. ULRIC DAHLGREN.; Curious Story Regarding the Disposition of his Remains.

Published: August 13, 1865From the Richmond Bulletin, Aug. 5.

The month of March, 1864, is memorable in Richmond for one of the grandest Union raids that up to that time had menaced the Confederate capital — a raid which was the immediate precursor of Gen. GRANT’s famous campaign from the Wilderness to James River. The history of this raid is too familiar to the minds of all of our readers to make necessary any recapitulation of it, even if it comported with our space. It is known that COL. DAHLGREN, after the attack on Richmond on Tuesday, the 1st of March, did not succeed in forming a junction with Gen. KILPATRICK, and while passing through King and Queen Counties, toward Gloucester Point, was killed, on the night of Wednesday, March 2, near Walkerton. It is also known that his body was brought to Richmond, but what disposition was made of it by the Confederate authorities was kept a mystery at the time, and the facts, even to this day, have never been published. We purpose to give them to the public for the first time, vouching for their entire authenticity.

When intelligence was received in Richmond of the death of Col. DAHLGREN, messengers were sent to bring it to the city for identification. It reached the city on Monday, March 7, by the York River Railroad, and laid during that day at the depot, where it was examined by large numbers of persons. His death had been caused by a gun-shot wound in the head. The little finger of one hand had been cut off on the field where he fell by some one anxious to secure, with the least trouble, a valuable diamond ring. That night the body was carried to Gen. ELZLY’s office, in Belvin’s block, and the next day. having been placed in a common pine coffin, of the kind then used for the burial of soldiers, which in turn was placed in a box, was transferred to the Oakwood Cemetery, a mile east of the city. The hearse used on this occasion was a four-mule street wagon, and the attendants consisted of a Confederate officer of inferior rank and two soldiers. Arriving at Oakwood, which was the burial place or all soldiers who died at Chimborazo, Howard’s Grove, and other hospitals in the eastern portion of the city and suburbs, the negro grave-diggers and other attendants about the cemetery were driven off and ordered to absent themselves until notified that they might return. One of the negroes, now living in the city, having his curiosity excited, secreted himself in the woods near by determined to see what was to be done. The two soldiers dug a grave, placed the box in it and covered it up. They then shouted to recall the attendants of the cemetery, and getting into the wagon, returned to the city. The only circumstance in the proceedings that struck the negro as unusual was the mystery observed and the circumstance of the box, no corpse ever having been brought there before except in a pine coffin; but there having been a great deal of talk as to what was to be done with the body of Col. DAHLGREN, he at once decided that this could be no other than the corpse of that officer. He, however, kept his opinion to himself at the time.

The question, what had been done with the body of DAHLGREN? was the subject of inquiry and conversation for many days in Richmond, to be revived from time to time up to the day of the evacuation. And there were many stories on the subject — that it had been burnt, sunk in the river, &c. A city paper of that day announced, with a solemn and knowing air, that it would never be found until the trump of doom should sound. A number of Union men of the city, believing it possible that it might be recovered, were anxious to secure and preserve it for the family of the deceased. Prominent among them was Mr. F.W.E. LOHMAN, a grocer, doing business near the New Market. Mr. LOHMAN at once began his inquiries and investigations — which, in the then state of popular feeling, it was necessary to conduct with great caution — determined, at whatever cost and risk, to ascertain its fate. After nearly a month’s patient and untiring inquiry, he, with the assistance of Mr. MARTIN MEREDITH LIPSCOMB, whose business it was to attend the interment of all Union prisoners who died at this post, made the acquaintance of the negro grave-digger, whom we have mentioned as being the sole spectator of the burial of Col. DAHLGREN. They found him at Oakwood, pursuing his regular business. When first approached on the subject, the negro was very much alarmed, and protested he would have nothing to do with the matter. But after repeated assurances by Mr. LIPSCOMB, whom he knew well, that he might rely upon LOHMAN, and that no harm should befall him, he consented, on Mr. LOHMAN’s giving him a hundred-dollar note, to point out the grave. This he did by walking near and casting a stone upon it, while LOHMAN and LIPSCOMB stood at a distance. He was afraid to employ any other method lest he might excite the suspicion of the superintendent of the cemetery or some of the attendants. The grave lay among thousands of those of Confederate soldiers. Subsequently, after a great deal of persuasion and the promise of a liberal reward, the negro agreed to meet Mr. LOHMAN at the cemetery on the night of the 6th of April, at 10 o’clock, and exhume the body.

The appointed night having arrived, Mr. LOHMAN, his brother, JOHN A. LOHMAN, and Mr. LIPSCOMB, started for the cemetery in a cart drawn by a mule. The night was dark and stormy, and well suited to conceal their movements. The party left the city at 9 o’clock, and reached their destination about 10, and there found waiting for them the grave-digger and two assistants. The negroes being assured that all was right, began their work of exhumation, the three white men remaining with the cart outside the inclosure of the cemetery. The heavens were hung with their deepest black; no object ten feet distant could be distinguished, and no sounds broke upon the loneliness of the place save the howling of the winds and the resurrectionist’s spade. Once the mule, snuffing the tainted air of the city of the dead, attempted to break away, but was quickly quieted by a firm hand.

In twenty minutes from the time the negroes began their work they approached the cart, bearing between them the coffin, which, being badly made, fell to pieces as they rested it on the ground. It was then discovered that the body bad not decomposed in any perceptible degree. Mr. LOHMAN satisfied himself of the identity of the corpse by passing his band over it. The little finger, torn off to secure the jewel it bore, and the leg, lost in battle, were missing. He paid the negro with whom he had contracted fifteen hundred dollars, and placing the body in the cart, the party started on their return. The mule, alarmed as animals frequently are when drawing a dead body for the first time, become difficult of management, and with the darkness of the night, made the first part of the expedition one of no little peril. More than one hour was spent in reaching the gaslights of the city on Church Hill. It was part of the plan to convey the body to the house of WILLIAM S. ROWLETT, a Union man, living on Chelsea Hill, a half mile northeast of the city, there to remain until a metallic case could be procured for it. From Church Hill, Mr. LOHMAN drove down Broad-street to Seventeenth-street, thence up Seventeenth-street to its northern terminus, and thence up the hill to Mr. ROWLETT’s, reaching the last place at 2 o’clock on the morning of the 7th of April. Here the body was wrapped in a blanket, and Mr. LOHMAN came to the city in search of a coffin, which he obtained by the aid of Mr. LIPSCOMB. On his way into the city from ROWLETT’s, LOHMAN notified a number of persons of Union sentiments, among whom were several ladies, where the body had been placed, and they hurried out to see it. Several of these persons had seen Col. DAHLGREN while he was exposed at the York River Railroad depot, and immediately recognized the body as his. The metallic coffin having been procured, and the body placed in it, the two LOHMANS, at noon on the 7th, set out with it, concealed, in a wagon loaded with young fruit trees, for the farm of ROBERT ORRICKS, a Union man, living in Henrico, two miles from Hungary Station.

At 4 o’clock that evening they reached ORRICKS’, and buried the body under an apple-tree in a field, avoiding the graveyard for tear of exciting inquiry, which might lead to discovery.

The rest of this story may be told in a few words. ORRICKS, some months after the second burial of Col. DAHLGREN, succeeded in getting through the Confederate lines, and seeking an interview with Com. DAHLGREN, informed him of what had been done to secure the body of his son. The corpse of the soldier laid in this, its second grave, until the evacuation of Richmond, when an order having been sent for it by the War Department, it was again disinterred by the two LOHMANS and sent to Washington.

It has been our object to left the veil of mystery from an obscure and interesting event. In doing so, we have confined ourselves to facts strictly relative to the secret fate of Col. DAHLGREN’s body from the time of its arrival in Richmond, which, until after the capture of the city, remained, to all except the few individuals named by us in the course of our narrative, one of the most impenetrable mysteries of the war. Many Confederate officials knew that the body had been deposited at Oakwood, but they were ignorant to the last that it had ever been removed. It has at length found its last resting place.

This is a largely accurate description of a fascinating event with all of the hallmarks of a great thriller.

Scridb filterDr. Matt Lively, a physician from West Virginia, who will have a book released by Savas Beatie later this spring titled Calamity at Chancellorsville that focuses on the accidental mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson. Matt has begun a new blog. It’s called Civil War Profiles, and it features profiles of historic figures and their feats. There are only a few posts there now, as it’s a new blog, but it looks interesting. Check it out.

I’ve added a link for it.

Scridb filter1863 Gettysburg Before and AfterThe Hagerstown Community College is putting on an interesting Civil War Seminar on Saturday, March 23, 2013. The topic of the seminar is before and after the Battle of Gettysburg. I’ll be presenting about the retreat from Gettysburg. I’ve included a link to the brochure for the event in this post. I hope to see some of you there.

Scridb filter On one of the forum boards that I regularly visit, someone asked for examples of infantry forming squares in echelon to defend against cavalry charges. The first response on the list was Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s Confederate infantry brigade forming square at Gettysburg on July 1.

On one of the forum boards that I regularly visit, someone asked for examples of infantry forming squares in echelon to defend against cavalry charges. The first response on the list was Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s Confederate infantry brigade forming square at Gettysburg on July 1.

There’s a problem with that response. There is no proof that it happened. And it completely ignores the documented instance of Confederate infantry forming square to defend against a feinted cavalry charge that DID occur earlier in the afternoon of July 1, 1863.

For those unfamiliar with forming squares in echelon, it’s a classic Napoleonic tactic for infantry to defend against a cavalry charge. A good, concise explanation of the tactic, and how to try to break a square, can be found here. Yes, it’s a Wikipedia article, but it’s a good one and it is accurate. The photo is of a Union infantry regiment, formed up in a hollow square. Click on the photo to see a larger version of it.

Here’s the story about Lane’s supposed forming squares:

A determined attack by the Confederate infantry brigade of Col. Abner Perrin finally broke the last Union line of resistance on Seminary Ridge, driving the First Corps back toward Cemetery Hill. At 4:00 p.m., in imminent danger of being flanked by Perrin’s advance, Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, the acting commander of the First Corps, sent staff officer Capt. Eminel P. Halstead in search of Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard, then overseeing efforts to cobble together defenses on East Cemetery Hill, looking for reinforcements. When Halstead reported the Confederate threat, Howard informed him that he had no reinforcements to spare, and suggested that Halstead “go to General [John] Buford, give him my compliments, and tell him to go to Doubleday’s support.” When Halstead asked Howard where to find Buford, Howard indicated that he did not know, but that he thought Buford was somewhere to the east of Cemetery Hill. Halstead set off to search for the Kentuckian.

After they were driven from the stone wall they had held until Perrin’s attack broke the Union line, Buford ordered Col. William Gamble’s weary troopers to fall into line on the Emmitsburg Road, where they were later joined by Devin’s brigade. There, Halstead found Buford, mounted on his thoroughbred war horse, Grey Eagle, overseeing the disposition of his cavalry. When Halstead delivered Howard’s order, the irate Buford “rose in his stirrups upon his tiptoes and exclaimed, ‘What in hell and damnation does he think I can do against those long lines of the enemy out there!’”

Halstead responded, “I don’t know anything about that, General, those are General Howard’s orders.”

“Very well,” replied Buford, “I will see what I can do.” Around 5:00 p.m., Buford ordered his mounted command to move out into the fields in front of Cemetery Hill, in plain view of the enemy. The sight so impressed Second Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, sent by Meade to take command of the field, that he later recalled that, “one of the most inspiring sights of his military career was the splendid spectacle of that gallant cavalry, as it stood there unshaken and undaunted, in the face of the advancing Confederate infantry.”

Gamble sent elements of the 8th Illinois forward to remove fence rails and other impediments to a mounted charge. In line of battle, Buford’s exhausted troopers stood their ground, daring the Confederates of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s brigade to attack. Doubleday noted in his diary that night, “Having thus strengthened his right, General Hancock extended his line by posting Buford’s Cavalry…on the left. This gave us an appearance of strength we did not possess and the enemy did not press the attack, preferring to wait for reinforcements.” Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, the Army of the Potomac’s chief engineer, later recorded, “General Buford’s cavalry was all in line of battle between our position [on Cemetery Hill] and the enemy. Our cavalry presented a very handsome front, and I think probably checked the advance of the enemy.” Doubleday’s aide Halstead recounted, “the enemy, seeing the movement, formed squares in echelon, which delayed them and materially aided in the escape of the First Corps if it did not save a large portion of the remnant from capture.” Doubleday later recounted that with the feinted charge, Buford “rendered essential service…and prevented them from cutting us off from our line of retreat to Cemetery Hill.”

The problem is that Halstead’s post-war account–published in a paper that he presented to the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (a Union officers’ veterans’ organization)–is the ONLY source that claims that Lane formed square. None of the participants mentioned it in their contemporary after-action accounts. None of the other memoirs, letters, and other primary sources mention it. It simply cannot be corroborated by anyone. Undoubtedly, SOMETHING halted Lane’s advance that day. It was probably the sight of two full brigades of cavalry–roughly 2700 troopers–mounted, in line of battle, with sabers drawn, awaiting the order to charge. But there is no evidence that Lane actually gave the order to form squares by echelon, and there is no evidence that they actually did so. Instead, it appears that the feint was enough. Lane’s advance halted, which allowed time for the Union infantry to fall back safely from its very exposed position on Seminary Ridge to the positions that Hancock and Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, the Army of the Potomac’s chief engineer, had prepared on East Cemetery Hill.

The story of Lane’s Brigade overlooks another instance that day when Confederate infantry did, indeed, form square against a feinted charge by troopers of the 8th Illinois Cavalry of Gamble’s brigade.

About 1:00, advancing Confederate infantry of Brig. Gen. James J. Pettigrew’s brigade threatened the left flank of the First Corps near the end of modern-day Reynolds Avenue. Col. Chapman Biddle’s brigade held the end of Doubleday’s line. Biddle’s men were in grave danger of being flanked by the 52nd North Carolina Infantry of Pettigrew’s Brigade. A deep swale hid the Confederates’ advance and allowed the Tarheels to approach Biddle’s flank unseen.

From his vantage point, Gamble could see the threat, and he ordered Maj. John Beveridge, commanding the 8th Illinois, to take his regiment out to the southwest, along the Hagerstown Road, where they took position in an orchard south of the road, near woods.

Beveridge “ordered the 8th Illinois, in column of squadrons, forward, increased its gait to a trot as if to make a charge upon [the Confederate] right. His right regiment halted, changed front, and fired a volley: Biddle’s brigade rose to their feet, saw the enemy, fired and retired across the field toward Seminary Ridge.”

The men of the 52nd North Carolina stopped dead in their tracks and formed a hollow square. A member of the 52nd recalled:

[the 52nd North Carolina] held the right of Pettigrew‘s line, and as we advanced through the open field our right flank was menaced by a body of the enemy’s cavalry, seeking an opportunity to charge our lines. While on the advance and under heavy fire Col. [James K.] Marshall formed his regiment in square to guard against attack from this body, and at the same time deployed Company B…to protect his flank. [They] succeeded in holding the cavalry in check and finally drove them from our flank. This maneuver was executed by the regiment as promptly and accurately as if it had been upon its drill grounds.

Maj. William Medill of the 8th Illinois proudly observed that his regiment

saved a whole brigade of our infantry and a battery from being captured and cut to pieces. The rebels had them nearly surrounded and hemmed in, perceiving which, we made a detour to our left, gained their flank, and charged right on the rear of one of the living walls that was moving to crush our infantry. The rebel line halted suddenly, faced about, formed to receive us, and fired a volley that mostly went over our heads. We returned fire with our carbines and galloped away. But during the time they were delayed, the infantry escaped.

The mission accomplished, the 8th Illinois fell back to rejoin the rest of Gamble’s brigade southwest of the Federal line.

This critical episode saved Biddle’s brigade from being flanked and permitted it to withdraw safely to Seminary Ridge. Yet, it is completely overlooked. Instead, it gets lost in the shuffle of the legend of Lane’s Brigade forming square, when it probably never happened. It’s a shame, because the stand by Beveridge’s men was a critical moment. That’s not to downplay what John Buford and his troopers did, as the very threat of a mounted charge by 2700 Union troopers clearly brought Lane’s advance to a screeching halt. What’s not clear, though, is whether Lane formed square, as it cannot be corroborated.

This particular issue has fascinated me for years, and I’ve been wrestling with it since 1992. I’ve seen every known account of the events of that day, and the idea of Lane’s Brigade forming square, romantic as it may be, just can’t be reconciled with those accounts. Hence, it does not appear that it occurred.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like