Author:

Way back in the fall of 1981, the first semester of my junior year in college, I participated in a wonderful program sponsored by American University called the Washington Semester. Students from colleges and universities all over the country send students to AU for this program. When I was there, there were 35 of us from my alma mater, Dickinson College, by far the most participants from any school. I did the foreign policy program, meaning that I did an internship two days per week, we had seminars around Washington two days per week, and Friday was reserved for a large independent study paper due at the end of the semester. At no time in my life did I learn more, study less, have more fun, or get better grades. It was a fabulous experience that I recommend highly.

AU’s campus is in the far northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., at Ward Circle, where Nebraska Avenue and Massachusetts Avenue intersect. It’s one of the nicest parts of the District, at the northern end of Embassy Row, near the new Russian Embassy and the Japanese Embassy, a few blocks down Wisconsin Avenue from Tennally Circle. The University sits on a plateau that rises from the Potomac River from Georgetown.

Tuesday night was a big party night, and the University had its own on-campus pub in the student union building, not far from Ward Circle. We spent a lot of fun Tuesday nights there, drinking cheap, bad beer, and doing the sorts of stupid things that college students do as a consequence of drinking cheap, bad beer.

What does this have to do with the Civil War, you ask? Good question.

In the course of working on the Monocacy project, J.D. and I have decided to focus on Early’s advance on Ft. Stevens and the probes of the defenses of Washington by his army. Brig. Gen. John McCausland commanded a brigade of Virginia cavalry attached to Early’s army. McCausland claimed that he actually penetrated the defenses of the Federal capital, and that he could see the Capitol from the high ground in front of an abandoned fort briefly held by his men. This is one of those intriguing little obscure incidents of the Civil War that catch my attention and which cause me to want to learn more.

McCausland’s account is tantalizing and at the same time frustrating. He does not name the fort that he claimed that he occupied, but claimed it was in or near Tennallytown. Most people who have looked at this incident have indicated that they believe it was Fort Gaines, which was located in the northwest quadrant of the city, and the fort with the highest elevation. However, recent historical detective work suggests that rather than Fort Gaines, the fort was actually Fort Reno, named for Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno, commander of the 9th Corps, and who had been killed during the September 1862 Battle of South Mountain. I’m convinced.

McCausland’s account is tantalizing and at the same time frustrating. He does not name the fort that he claimed that he occupied, but claimed it was in or near Tennallytown. Most people who have looked at this incident have indicated that they believe it was Fort Gaines, which was located in the northwest quadrant of the city, and the fort with the highest elevation. However, recent historical detective work suggests that rather than Fort Gaines, the fort was actually Fort Reno, named for Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno, commander of the 9th Corps, and who had been killed during the September 1862 Battle of South Mountain. I’m convinced.

Fort Reno occupied precisely the same ground as the front portion of the American University campus. The dormitory where I stayed for the semester would have been located directly behind the spot occupied by Fort Reno. But for the high-rise apartment buildings that clutter the skyline and block the view of downtown Washington, you would be able to clearly see the Capitol dome from there. Therefore, although there are no historical markers to suggest that the university’s campus had historical significance, and I had no way of knowing it, I spent an entire semester living–and partying–on some very important historic ground that is directly relevant to our Monocacy project.

Just think…I might have been drinking bad beer on the very spot where McCausland stood and visually inspected the defenses of the Federal capital. And I never knew it.

We’ve decided that we definitely need to include this episode in the driving tour portion of the Monocacy study, which will take me back to AU’s campus for the first time in more than 20 years. Won’t that make for an interesting trip down memory lane?

Scridb filterHat tip to Rea Redd for bringing this sad story to my attention. It’s a shame that flogging is considered cruel and unusual punishment.

Man arrested in eBay sale of historic documents

Tue Jan 29, 2008NEW YORK (Reuters) – A New York state employee who had access to government-owned archives has been arrested on suspicion of stealing hundreds of historic documents, many of which he sold on eBay, authorities said on Monday.

Among the missing documents were an 1823 letter by U.S. Vice President John C. Calhoun and copies of the Davy Crockett Almanacs, pamphlets written by the frontiersman who died at the Alamo in Texas.

Daniel Lorello, 54, of Rensselaer, New York, was charged with grand larceny, possession of stolen property and fraud. He pleaded innocent in Albany City Court on Monday.

He was found out by an alert history buff who saw the items posted on the online auction site and alerted authorities, the state attorney general’s office said in a statement.

Lorello, a department of education archivist, pleaded not guilty to the charges although he previously admitted in a written statement to stealing documents and artifacts since 2002. The attorney general’s office released a copy of his statement.

In 2007 alone, Lorello stated he took 300 to 400 items, including the four-page Calhoun letter, which drew bids of more than $1,700 while investigators were monitoring the sale.

Officials recovered some 400 items from his upstate New York home, which Lorello estimated was 90 percent of everything he had taken, but they have yet to determine how many items were sold online.

Other items Lorello admitted in his statement to stealing and selling included an 1835 Davey Crockett Almanac, which fetched $3,200, and a Poor Richard’s Almanac which went for $1,001.

EBay was cooperating with state officials in the probe.

The real tragedy of this is that I actually know Dan Lorello. A number of years ago, when I was writing my book Little Phil, the issue of whether Phil Sheridan had been born in Albany, NY arose. I knew Dan from having him help me with getting materials from the papers of William Woods Averell for a prior book project, and I wanted to see what records there were of Sheridan’s possible birth in Albany, which is what Sheridan himself claimed. Dan did some digging for me and confirmed what I suspected, which is that no such records existed (for good reason–Sheridan was born in Ireland, and those records do, in fact, exist). Later, I wanted to include a photo of the equestrian monument to Sheridan that sits outside the state capitol building in Albany in the book, and Dan took that photo for me. In fact, the photo in the book is credited to him.

To say that I’m profoundly disappointed does not do it justice. I never would have guessed that Dan would be the sort to do this kind of thing, but then again, nobody ever really knows….

All I know is that Dan deserves whatever he gets in the way of punishment, and that whatever that might be, it’s not enough.

Scridb filterI wanted to introduce some of you to one of my favorite niche publishers, Tony O’Connor’s Vermont Civil War Enterprises. Tony lives in Newport, Vermont, and has created a nifty little niche for his business. Tony publishes books only on Vermont’s contributions to the Civil War.

Tony produces a really high quality book. Some are leather bound, and others are well bound in fabric with gold lettering. His offerings run the gamut from replica reprints of long out of print works, such as regimental histories and the reports of the Reunion Society of Vermont Officers to new works, such as a very nice regimental history of the 3rd Vermont Infantry of the Old Vermont Brigade. The books are not inexpensive, but they’re high quality and they’re definitely worth owning.

If Vermont’s contributions to the Civil War are of interest to you, then Tony O’Connor’s website is definitely a place for you to visit and for you to indulge your book addiction.

Scridb filterHaving decided that we were going to take on the Monocacy project, I’ve immersed myself into the process of gathering research ideas and sources so as to develop our research strategy. Doing so is not only wise, it saves a lot of aggravation because we lay out a roadmap and then follow it to its conclusion. Of course, things always turn up unexpectedly and have to be dealt with, but for the most part, we try to stick to the plan.

Today, I spent some time going through the reference bibliographies of the U. S. Army’s Heritage Collection Online, looking for sources to use in the course of researching the Monocacy project. As I made my way through the many Virginia regiments that made up Early’s army, I noted that one of the available sources was through a self-publishing venue called Lulu.com. There are others, but Lulu is the only one of these companies that I have ever used.

Lulu provides an opportunity for authors to self-publish their work without having to incur the cost of printing, etc., as Lulu is a print-on-demand publisher (“POD”). The company charges nothing for the actual publishing of the work since it’s all POD. The company charges $100 for a POD author to use the company’s distribution network, which is pretty much limited to the Lulu.com website. Editorial services are available for a fee, but my guess is that a lot of things get published there without the benefit of an editor’s services. You lay out your own work by following the templates that they recommend, send a PDF, and voila: you’re a published author.

Clearly, there is nothing like peer review of the work. Nobody vets this stuff to see whether it is historically accurate, or whether it’s worthy of publication. Companies like Lulu.com certainly democratize the publishing process, but, at the same time, they water it down by allowing anything to get into print irrespective of whether it’s worthy of publication. Personally, I find it difficult to take Lulu.com’s offerings seriously just for that reason. I guess it takes a case-by-case assessment to determine whether something is worthy or not. The particular volume that I was contemplating today is a set of soldier letters, so I have to imagine it might be worth investing in, simply because it’s difficult to screw up the transcription of someone else’s written words. However, I would have to think long and hard about one of their titles if it involved interpretation and analysis because I would not have any confidence that the work was reliable.

In fairness, Lulu.com does offer one extremely valuable service, and it’s one that I have utilized. For those willing to do the work to scan a public domain work that’s long out of print, Lulu.com’s POD model makes it possible to bring back books that otherwise would not pay to bother with. Virtually the entire catalog of Twin Commonwealths Publishers is done this way. The owners of Twin Commonwealths have scanned any number of extremely rare out-of-print works and made them available for purchase through Lulu.com’s POD model. I’ve purchased a couple of them, and they’re worth owning. For that sort of application, I can recommend the likes of Lulu.com.

Also, something like Lulu.com might be a fabulous way to keep the H. E. Howard Virginia Regimentals Series alive. It would make the books readily available to anyone who wanted them, but would not require the publisher to maintain any inventory. It seems to me that this would be a win-win resolution. I wonder if anyone has discussed this option with Harold Howard…..

Scridb filterIn the 1980’s, a publisher from Lynchburg, Virginia named Harold Howard undertook a magnificent–and pretty much unparalleled–project when he decided to publish a history of EVERY regiment, battalion, or battery fielded by the Commonwealth of Virginia during the Civil War. The scope of the project is really pretty staggering. The series itself is a mixed bag. The books are of mixed quality. Some are definitely better than others, and some are really bad. Fortunately, they were always very affordable, with many of the volumes priced at $19.95.

There are a number of gripes that spread across the spectrum of the series. The production values are inconsistent at best. There is almost no detail in the history section of each book, and there are no footnotes. As research resources, they leave a great deal to be desired. Few of the maps are original, and most of them appear in more than one volume. They contain very little detail. The duplication of photos is pretty shoddy–they’re universally very dark and often hard to make out.

The best aspect of the series is that each volume contains a complete regimental roster, and those rosters often contain extremely useful information. I don’t know this specifically, but I’ve heard this several times from several sources, which is that the information contained in these regimental rosters came from the extensive files accumulated by Bob Krick.

In spite of everything, the series is unique–there is nothing else like it. Overall, the series is useful and has been a worthy addition to the body of knowledge.

Today, in corresponding with Clayton Thompson, one of the booksellers I regularly deal with, I learned that Mr. Howard has allowed nearly 60 of the titles in the series to go out of print, and that many of the remaining titles are in very low stock. In short, the series will be extinct before much longer. For those who are interested in adding volumes from the series to your libraries, I highly recommend that you move quickly to do so.

Personally, I think it’s sad. As I said, it was a unique and groundbreaking series that has added a lot to the body of knowledge, and I hate to see it drift away.

Scridb filterChris Army, whom I’ve known for years as a Gettysburgaholic, has started a new blog. Chris only has two posts so far, so it’s hard to predict what the future holds, but knowing Chris, I believe it will be a good addition to the blogosphere. I’ve added a link.

Welcome to the blogosphere, Chris.

Scridb filterFor those who might be interested, I wanted to announce a couple of upcoming events I’ve committed to attending.

First, I have accepted an invitation to be the keynote speaker at the commemoration of Jeb Stuart’s birthday in Richmond on February 9. The program is sponsored by the Stuart-Mosby Historical Society. The event begins at 11:00 with a wreath-laying ceremony at General Stuart’s grave in Hollywood Cemetery, and then there is a luncheon at the lovely downtown Commonwealth Club. I will be the lunchtime speaker, and will be doing a presentation on Stuart’s ride during the Gettysburg Campaign. Susan and I will be flying into Richmond that Saturday morning.

The other event I’ve committed to attending is my friend Mark Snell’s excellent annual summer conference of the George Tyler Moore Civil War Center at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. This year’s program is Gettysburg Retreat and Pursuit, and will be held June 26-29. I’m kind of the star of the show in that I’ll be leading a half day tour of the route of the Wagon Train of Wounded and a full day tour of the fighting along the retreat route. Kent Masterson Brown will be on the program, as will old friends Ted Alexander and Tom Clemens. Mark runs a first-rate conference, and I was really excited when he asked me to participate.

For those interested in the retreat from Gettysburg and the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia, this will be a can’t-miss program.

I hope to see some of you at one or both of these events.

Scridb filterOne of the reasons why the Battle of Monocacy fascinates me is that it represents one of the only instances during the Civil War where militia not only stood and fought, but did so quite effectively. The northernmost portion of the battle occurred at the stone “jug” bridge, which carried the National Road across the Monocacy River.

Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace’s Federal command consisted of three brigades. Two of those brigades belonged to Brig. Gen. James Ricketts’ Third Division, Sixth Corps. These two brigades did the bulk of the fighting, on the main battlefield. The third brigade, consisting of troops from the Eighth Corps, a hodgepodge command based in Baltimore, was made up largely of 100 days’ militiamen raised as emergency troops. The better part of two regiments of Ohio troops made up the bulk of this command. These men were completely untried, and they had very little in the way training.

Col. Allison L. Brown commanded these men. There were also a regiment and a half of the Maryland Potomac Home Guard, the 11th Maryland, and 6 guns of a Baltimore battery. These men were not the sort of men one would expect to stand and fight long and hard against Confederate veterans, but that’s exactly what they did. They stood and fought all day long against Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ veterans, and were the last men to leave the battlefield, even after Ricketts’ troops had been driven from the field by Early’s men. They were left to their own devices and to get away, each man for himself.

The courageous and unexpected stand of these militiamen at the Jug Bridge ensured that the bulk of Wallace’s command escaped from the battlefield and lived to fight another day. It was one of the few instances of the Civil War when militiamen not only stood and fought in the face of the enemy, but did so effectively and bravely.

We’re going to tell their story in detail in our tactical study of the Battle of Monocacy, hopefully, in greater detail than it’s ever been told previously. I hope to do these forgotten soldiers justice in the process.

Scridb filterAfter more than six months without a single post–I had written it off as a dead blog–Touch the Elbow, the excellent blog by the authors of the regimental history of the 18th Massachusetts Infantry, is back! I always really enjoyed the insights of Tom and the others, and was very sorry to see the blog die. I’m even more pleased to see it back. I’ve added it back into the blogroll. Welcome back, guys.

Scridb filterMy profiles of forgotten cavalrymen usually focus on men whose outstanding contributions to their cause made a difference in the outcome of the war. Every once in a while, though, it’s fun to pay tribute to a scoundrel. Today, we pay tribute to a true rascal.

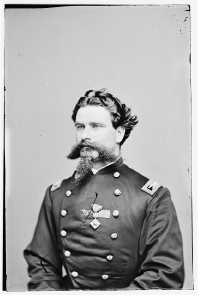

Col. Sir Percy Wyndham was born on the ship Arab in the English Channel on February 5, 1833, while his parents were en route to Calcutta, India. Capt. Charles Wyndham, his father, served in the British Fifth Light Cavalry. With that pedigree, the boy was destined to be a horse soldier. However, fifteen-year old Percy Wyndham entered the French navy instead, serving as a midshipman during the French Revolution of 1848. He then joined the Austrian army as a sub lieutenant and left eight years later as a first lieutenant in the Austrian Lancers. He resigned his commission on May 1, 1860 to join the Italian army of liberation being formed by the famed guerrilla leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, and received a battlefield promotion to major in the great battle of Milazzo, Sicily on July 20, 1860, where Garibaldi’s army defeated the Neapolitans, consolidating the guerrilla’s hold on the island. A grateful King Victor Emmanuel knighted the dashing cavalryman. With the conquest of Italy complete, the soldier of fortune went hunting for another opportunity, and found one in the United States in 1861.

Col. Sir Percy Wyndham was born on the ship Arab in the English Channel on February 5, 1833, while his parents were en route to Calcutta, India. Capt. Charles Wyndham, his father, served in the British Fifth Light Cavalry. With that pedigree, the boy was destined to be a horse soldier. However, fifteen-year old Percy Wyndham entered the French navy instead, serving as a midshipman during the French Revolution of 1848. He then joined the Austrian army as a sub lieutenant and left eight years later as a first lieutenant in the Austrian Lancers. He resigned his commission on May 1, 1860 to join the Italian army of liberation being formed by the famed guerrilla leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, and received a battlefield promotion to major in the great battle of Milazzo, Sicily on July 20, 1860, where Garibaldi’s army defeated the Neapolitans, consolidating the guerrilla’s hold on the island. A grateful King Victor Emmanuel knighted the dashing cavalryman. With the conquest of Italy complete, the soldier of fortune went hunting for another opportunity, and found one in the United States in 1861.

Sir Percy offered his services to the Union with the coming of war in the spring of 1861. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who quickly rose to command all of the Union armies, was familiar with Wyndham’s reputation as a fighter, and recommended him to be the colonel of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry. Although the governor of New Jersey issued the commission in February 1862, the men of the 1st New Jersey did not welcome the Englishman with open arms. A local newspaper wondered, “Have we no material in New Jersey out of which to manufacture competent colonels without resorting to foreigners to fill up the list?” However, when he instituted discipline, improved their food, got regular pay for his men, and moved their camp out of a swamp, the troopers changed their minds about their new commander.

Sir Percy made quite an impression. A Federal horseman recalled, “This officer was an Englishman, an alleged lord. But lord or son of a lord, his capacity as a cavalry officer was not great. He had been entrusted with one or two independent commands and was regarded as a dashing officer…He seemed bent on killing as many horses as possible, not to mention the men. The fact was the newspapers were in the habit of reporting that Colonel or General so-and-so had made a forced march of so many hours, and it is probable that ‘Sir Percy’ was in search of some more of that kind of cheap renown.”

One Confederate trooper noticed that Sir Percy, who wore a spectacular mustache nearly two feet wide, was “a stalwart man…who strode along with the nonchalant air of one who had wooed Dame Fortune too long to be cast down by her frowns.” A Federal officer called Wyndham “a big bag of wind.” Another Northerner, remembering his first encounter with Wyndham, compared him to a bouquet of flowers, noting, “You poor little lillies, you! You haven’t the first the glorious magnificence of his beauty. He’s only been in Camp for two hours, and he now appears in his third suit of clothes!”

During Jackson’s Valley Campaign of 1862, Wyndham impetuously led his regiment in a charge into Turner Ashby’s cavalry, and Wyndham was captured on June 6, 1862. He was paroled on August 17. When he returned to duty, he was assigned to command a brigade in Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard’s cavalry division.

Wyndham’s brigade included his own 1st New Jersey Cavalry, the 12th Illinois Cavalry, the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, and the 1st Maryland Cavalry. In early 1863, while his brigade was headquartered at Fairfax Court House, Wyndham was given the task of running down the guerrillas of John S. Mosby. Sir Percy did not approve of Mosby’s unorthodox tactics, and called him a horse-thief. Sir Percy threatened to burn down towns if their inhabitants did not tell what they knew about the whereabouts of Mosby and his men, a policy that did not endear the Englishman to any of the locals.

Offended by being called a horse thief, Mosby decided a personal response was in order. When a deserter from the 5th New York Cavalry disclosed the location of Wyndham’s headquarters, Mosby raided the place on the night of March 9, 1863. Sir Percy had left for Washington the day before, and missed the humiliation of being captured in his bed, as two of his aides and Brig. Gen. Edwin M. Stoughton were. Mosby had to content himself with capturing some of Sir Percy’s uniforms.

Sir Percy’s brigade performed well during the Stoneman Raid of 1863, reaching the outer defenses of Richmond before turning away. His finest moment was at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. He personally led his brigade’s charge up Fleetwood Hill, engaging in hand-to-hand combat until they were driven back by the weight of enemy numbers. Although his troopers were badly outnumbered, he personally rallied a rear guard and forced the pursuing Confederates back with two hell for leather saber charges. Sir Percy received a severe gunshot wound to the leg, but stayed in the saddle until loss of blood finally forced him to retire. “It affords me no small degree of pleasure to be able to say that all of my command that followed me on the field behaved nobly,” he proudly wrote of his brigade’s performance, “standing unmoved under the enemy’s artillery fire and, when ordered to charge, dashing forward with a spirit and determination that swept all before them!”

Sent to Washington to recuperate, he assumed command of the cavalry units assigned to the capital’s defenses. During Stuart’s advance on Washington on his way into Pennsylvania, Sir Percy scraped together a force of 3,000 fully equipped horsemen, but they did not end up facing the enemy.

When he returned from a leave of absence in October 1863, he was charged with “absence without leave”, his leave having expired on September 5. He was relieved from all duty “and ordered to proceed to Washington, but not in arrest.” On October 3, 1863, Sec. of War Edwin M. Stanton issued an unusual order: “Information received at this Department indicates that Colonel Percy Wyndham should not be permitted to have a command or come within the lines of [the Army of the Potomac].” Historian Roger Hunt speculates that this order stemmed from rumors that Wyndham was involved in a plot to kidnap Lincoln and his cabinet. Sir Percy repeatedly applied for reinstatement, but was rebuffed.

Undaunted, he returned to the army in April 1864 in a volunteer capacity, “rendering all the service in my power for the advancement and success of the Union cause.” When Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, learned that Wyndham was with the army again without authority, on June 26, 1864, he ordered that Wyndham “be sent by the Provost Marshal General to Washington, in charge of an officer, and reported to the Adjutant General.” On July 2, Stanton ordered, “Colonel Wyndham will be mustered out of service,” effective July 5, 1864.

Now a civilian, Sir Percy settled in New York, where he established a military school. In 1866 he returned to Italy to serve on Garibaldi’s staff. When the Italian war ended, he and a friend who was a chemist went to New York to start a petroleum refining business. Unfortunately, an explosion destroyed the main refinery and ruined the business. Ever restless, he soon left New York for India. He settled in Calcutta and established a comic newspaper, The Indian Charivari, modeled on London’s Punch. He founded an Italian opera company and married a wealthy widow. A failed business logging teak in Mandalay, Burma, ate up all of the wealth earned from his Indian businesses.

Returning to his mercenary roots, he briefly served as the commander in chief of the Burmese army, but was left penniless by the failure of his many businesses. He was fascinated by huge balloons, and undertook the construction of one. In January 1879, the huge balloon (70 feet tall and 100 feet in diameter) exploded with him aboard at an altitude of 300 feet. The flamboyant English soldier of fortune was dead at the young age of 46. His body was not found.

Here’s to Col. Sir Percy Wyndham, English soldier of fortune, scoundrel, and wearer of some of the most spectacular facial hair ever seen on this continent.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like