Author:

We’re back home after 8 wonderful days in California. As I said before we left, there was no Civil War this trip. Instead, the trip was all about family and relaxing, which I desperately needed.

We flew Southwest. For those of you unfamiliar with Southwest, it’s kind of like the Greyhound of the sky. There is no assigned seating, and there are typically multiple stops on every flight. Our flight on the way home started somewhere else, had its first stop in San Jose, where we got on, went to Burbank, to Las Vegas (where we got off), San Antonio, and then on to Philadelphia, where it ended.

We changed planes in Las Vegas and flew home to Columbus from there. The flight crew that we had from San Jose to Las Vegas also changed planes and ended up on our same flight. Along the way, we had made friends with one of the flight attendants, who lives in York, PA, and whose husband is ex-military and is interested in Civil War history. She asked for a card with the name of Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg written on it.

When we got into Columbus, the flight attendant not only gave us a shout-out for having been with them all day, she gave my historical work a shout-out, too. I was shocked by it, and was also incredibly embarrassed by it. That has to rank in my top five embarrassing incidents. At the same time, it was incredibly flattering, and it was very thoughtful of her to do that.

That was pretty much the full extent of the Civil War stuff for the entire trip, except for my finishing up an article for Dana Shoaf for one of his magazines. It’s nice to be home, and it was really nice to get a break from both life and from my historical work.

Tomorrow, this blog will get back to its regular business. I hope you’ve enjoyed your break from my rantings. I know I did. 🙂

Scridb filterThis morning, Susan and I leave for a much-needed vacation. We’re headed to California for a week. There will be no Civil War on this trip, and I intend to take a much needed break from work, researching, writing, and, yes, blogging, too. We will be back on the evening of the 15th. Posting will resume on the 16th. Have a good week and enjoy your respite from me.

Scridb filterJust to show that I’m not just committed to the preservation of cavalry battlefields, here’s an opportunity to do some real good for the preservation of the battlefield at Franklin AND a way to gain a $10,000 corporate donation, too.

The Franklin’s Charge organization www.franklinscharge.org of Franklin TN is currently conducting a fundraising campaign to purchase the famous Carter Cotton Gin property, epicenter of the Nov. 30, 1864 Battle of Franklin and site of the death of Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne. A large payment on the property is due in early September and Franklin’s Charge is in the midst of a special urgent appeal.

Christie’s Cookies will donate $10,000 to whichever charity receives the most votes in an online “election.” You can help Franklin’s Charge win the $10,000 by taking 2 minutes of your time and voting.

Please go to http://www.ilovechristiecookies.com/contest/form.asp in the charity name field type “Franklin’s Charge”, in the city field type “Franklin” and in the state field type “Tennessee.”

Do some good. Take a minute and vote, and help to preserve one of the most important parcels of the battlefield at Franklin.

Scridb filterThe Land Trust of Virginia issued this press release today:

THE LAND TRUST OF VIRGINIA CREATES THE

DEBORAH WHITTIER FITTS BATTLEFIELD STEWARDSHIP FUNDMiddleburg, Va. (August 6, 2009) – The Land Trust of Virginia Board of Directors has created a new fund, called the Deborah Whittier Fitts Battlefield Stewardship Fund, as a means of recognizing and providing financial support for landowners interested in protecting properties where Civil War battles took place. Grants from the fund will be used to offset some of individual landowner’s expenses associated with putting battlefield acreage into easement.

The Land Trust of Virginia (LTV) currently holds easements on 25 Civil War battlefield properties covering more than 1,500 acres, including 912 acres of the Battle of Upperville, 517 acres of the Battle of Unison, 70 acres of the Battle of Aldie, and 33 acres of the Battle of Middleburg. LTV’s Board of Directors anticipates that LTV will pursue and accept even more easements on Civil War sites as the Deborah Whittier Fitts Battlefield Preservation Fund becomes more widely known.

A long-time professional journalist who reported for both the Loudoun Times Mirror and the Civil War News, Ms. Fitts was considered by many to be the nation’s leading journalist covering Civil War preservation issues. For more than a decade, Fitts wrote eloquently about the struggle to protect Virginia’s hallowed Civil War landscape. She covered many major Civil War preservation battles that made national headlines, such as the proposed Disney theme park near Manassas and the successful preservation of Brandy Station, as well as many other nationally significant Civil War battlefield preservation efforts.

Childs Burden, a member of LTV’s Board of Directors and a close friend and colleague of Deborah’s, said: “The preservation of the history of this beloved Commonwealth of Virginia played such an important part of Deborah’s life. She has played an equally important role in preserving our Commonwealth’s heritage. Deborah devoted much of her life’s work to writing and educating others about Manassas, Chantilly, Unison, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Brandy Station, Aldie, Middleburg, Upperville, The Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House, Mount Zion Church, and many other Civil War sites threatened by development.”

Last year, the Civil War Preservation Trust honored Deborah’s memory by conveying her, posthumously, the distinguished “Lifetime Achievement Award,” bestowed for journalistic excellence in educating her readers about the fragile status of our nation’s sacred battlefields. The Civil War Preservation Trust (CWPT) Board of Trustees also voted in June 2009 to render a $30,000 grant to the Land Trust of Virginia for the purpose of inaugurating the Deborah Whittier Fitts Battlefield Stewardship Fund. Another $15,000 has already been pledged, bringing the total fund to $45,000.

Jim Campi, spokesman for CWPT, asserted: “I speak for everyone on the CWPT staff when I say she has left a lasting legacy of education and preservation for which we are extremely grateful. Through her work at The Civil War News, Deborah spread her love of history and her passion for preservation to an army’s worth of readers across the country. Through her admiring readers, Deborah’s impact will continue to be felt for many years to come. Now, with the Deborah Whittier Fitts Battlefield Stewardship Fund, her work will live on through the preserved land she helped to save.”

For further information about the Deborah Whittier Fitts Battlefield Stewardship Fund, contact LTV Executive Director Don Owen at donlandtrustva@earthlink.net or LTV Board member Childs Burden at CBurden338@aol.com.

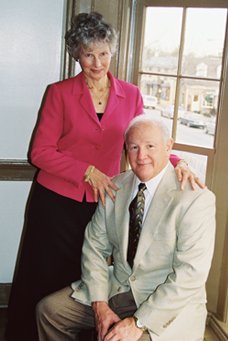

That’s Deb and her husband Clark “Bud” Hall in the photograph, taken not long before Deb was diagnosed with the cancer that took her life last year.

I can’t imagine a better tribute to her, nor can I think of a better way to honor her memory.

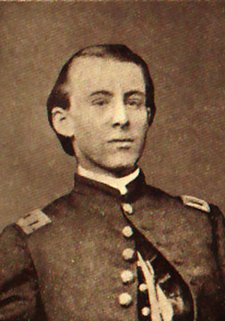

Scridb filter Time for another in my infrequent posts on forgotten Union cavalrymen. Today, we’re focusing on a little-known officer who commanded an even more obscure unit. Erastus Blakeslee was born to Joel and Sarah Marie Mansfield Blakeslee in Plymouth, Connecticut on September 2, 1838. He attended the Williston Seminary at Easthampton, Massachusetts for his college preparatory studies, and entered the freshman class at Yale University in the fall of 1859. He was on his spring vacation in 1861 when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, and he was one of the first from Plymouth to enlist in response to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers.

Time for another in my infrequent posts on forgotten Union cavalrymen. Today, we’re focusing on a little-known officer who commanded an even more obscure unit. Erastus Blakeslee was born to Joel and Sarah Marie Mansfield Blakeslee in Plymouth, Connecticut on September 2, 1838. He attended the Williston Seminary at Easthampton, Massachusetts for his college preparatory studies, and entered the freshman class at Yale University in the fall of 1859. He was on his spring vacation in 1861 when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, and he was one of the first from Plymouth to enlist in response to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers.

He enlisted in Company A of the 1st Battalion Connecticut Cavalry Volunteers on October 9, 1861. Nine days later, he was commissioned second lieutenant in the same company. On November 26, just over a month later, he was promoted to first lieutenant and was appointed regimental adjutant. On February 28, 1862, he was promoted to captain of Company A, which he commanded in the field.

On July 14, 1863, he was promoted to major, and assumed command of the regiment. On May 21, 1864, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and six days later, was promoted to colonel in a remarkably rapid rise. He went from private to colonel in two-and-a-half years. He was wounded in battle at the Battle of Ashland, Virginia on June 1, 1864, and returned to duty in time for the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. He mustered out on October 26, 1864 upon expiration of his term of service. Blakeslee was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers on March 13, 1865 for gallant conduct at Ashland, Va. on June 1, 1864. “He was a brilliant fighter,” observed one writer. “The General is the idol of his old regiment.”

Although the 1st Connecticut is a not a well-known regiment, it was engaged in a great deal of fighting during the Civil War. The State’s first cavalry regiment was organized as a battalion under Maj. J. W. Lyon in September 1861, and became a full regiment under Col. William S. Fish in November. It was sent to western Virginia to fight bushwhackers in March, 1862.

In the winter of 1862-1863 the regiment moved to Baltimore, Maryland for reorganization, and was serving there during the Gettysburg Campaign as part of the forces assigned to the Middle Military District. It moved to Harper’s Ferry, W. Va., July 5, 1863, and skirmished with southern cavalry in that vicinity until January, 1864.

After Blakeslee was promoted to colonel, the regiment became part of the Third Cavalry Division, Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac, fighting throughout the Overland Campaign, including at the Wilderness, Todd’s Tavern, Yellow Tavern, Meadow Bridges, throughout the Wilson-Kautz Raid, and then served in Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign from August to December 1864, fighting at Tom’s Brook and Cedar Creek. It then participated in Lee’s retreat from Petersburg, including fighting at Sailor’s Creek. The 1st Connecticut escorted Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to receive Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. The 1st Connecticut suffered 772 casualties during the war, representing 56% of its strength.

Blakeslee was also an inventor. With the advent of the Spencer repeating carbine, Blakeslee realized that his troopers would run out of ammunition quickly unless they had a way to carry large quantities of ammunition available to them. Blakeslee addressed this problem by designing the “Blakeslee Box”, which held ten ammunition tubes for the Spencer, meaning that each trooper could carry 70 rounds in tubes, ready to be loaded. More than 10,000 Blakeslee Cartridge Boxes were manufactured and distributed to the Federal cavalry during the course of the Civil War.

After the war, Blakeslee engaged in business in New Haven, Connecticut and then in Boston. In 1876, he resumed his studies, attending and graduating from Andover Theological Seminary. After graduating from there in 1879, he held Congregational Church pastorates in New Haven, Connecticut and Spencer, Massachusetts. While in Spencer, he became interested in an effort to improve the methods and result of Bible study in Sunday schools and among young people, and set about developing a system of study. In the summer of 1892, he resigned from his pastorate and moved to Boston, where he devoted his efforts to developing further improvements in the methods of Bible study.

He published numerous works on the Bible, including a nine-part study titled The Gospel History of Jesus Christ, that were translated into ten different languages, and were used in nearly all of the evangelical denominations in North America.

General Blakeslee lived the rest of his life in the Boston area, where he was active in veterans’ affairs, and regularly attended reunions of his old regiment. “At such times the Custer tie is the dominant color in the old cavalry organization,” noted a reporter in 1895.

He died July 12, 1908, and was buried in Walnut Hills Cemetery in Brookline, Massachusetts. He is one of the few officers to rise from private to colonel and regimental command. His genius led to the development of his cartridge box, and he then devoted his life to preaching the gospel. Here’s to Erastus Blakeslee, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filterI have finished my Brandy Station manuscript, and submitted it to the publisher over the weekend. I am waiting for my editor to let me know what the projected release date is, but I am told that there’s a reasonably good chance that they will get it out before the end of the year.

The manuscript features a walking/driving tour of the publicly accessible portions of the battlefield, 11 of Steve Stanley’s superb maps (published with the permission of the Civil War Preservation Trust), and about 50 other illustrations. It will also feature a foreword by Jim Lighthizer, the president of the CWPT, that discusses the fight to preserve the battlefield.

Part of my motivation in writing this book was that there be a good, reasonably detailed tactical overview of the battle, with good maps and an order of battle, that folks can purchase at the Graffiti House, which is the Brandy Station Foundation’s visitor center, and which can be used by the BSF as a fundraiser for its preservation efforts.

I’m going to take a month or so off from my Civil War research and writing duties–I am scheduled for a multi-day jury trial on September 1–and then I will begin working on the Yellow Tavern study in earnest once I get through that trial.

Scridb filterOn Thursday, I accepted an invitation that I was honored to receive. I have been invited to be the keynote presenter at the 20th anniversary picnic commemorating the founding of the Brandy Station Foundation, which will be on September 13, 2009, at Berry Hill Farm in lovely Culpeper County, Virginia. The event begins at 1:00, and I will be speaking between 2:30 and 3 on a subject that is near and dear to my heart, “Preservation and the Brandy Station Battlefield.

Scridb filterIn response to yesterday’s post, my friend Bud Hall has weighed in on the loss of the southern end of Fleetwood Hill. This was originally a comment to the post, but it is important enough that I decided to feature it as a main post here.

Back in 1984, I was transferred to FBI Headquarters in Washington, and soon bought a home in Virginia. Growing up in Mississippi on a cotton farm–and descended from a 13th Mississippi infantryman–I of course retained in my genes a compelling interest in the Civil War.

My very first weekend trips took me (and my maps) to Brandy Station. Map and primary source analysis, as well as discussions with land owners, convinced me that the entirety of this immense battlefield was nearly as untouched and as pristine as it was when fought over so savagely on June 9,1863.

Now fast forward to 1987 when a California developer arrived at Brandy Station with intent to insert a mammoth, corporate office park directly upon the battlefield… I do not herein purport to convey a history of the long, hard-fought preservation struggle at Brandy Station, but those who are interested in revisiting that sad–but largely successful–chapter of Brandy Station’s “modern” history can “Google” the names, “Clark B. Hall, and Brandy Station.”

By far, the most prominent, fought-over and militarily-vital topographical feature on the entire battlefield is Fleetwood Hill, a two-mile long ridge, that fronts the Rappahannock River, to the north. And on Fleetwood itself, the southern terminus is the ground upon which most of the truly-significant fighting took place.

Demonstrating incredible sensitivity to Brandy Station’s most significant battlefield feature, The Civil War Preservation Trust and the Brandy Station Foundation have purchased (for huge sums) highly significant, invaluable battlefield acreage on the northern and southern slopes of Fleetwood–for which both organizations are to be highly commended. It is a fact that major portions of Fleetwood are now protected, in perpetuity.

But it is also a fact that the most important part of Fleetwood is now “commanded” by an offensive, monolithic structure purported to be a family home, but which is in fact a startling monument to gross, historical insensitivity, and in-your-face, “architectural” extravagance, writ blasphemously obscene.

Now, better than anybody–except the “home’s” owner, and one other person–I know exactly what happened, the consequence of which resulted in the tragic construction of this home smack dab on top of Fleetwood Hill. Suffice it to say: There were private discussions between the landowner, another party and myself, and these discussions broke down hard and bitterly–to my utter dismay…

The outcome of this preservation disaster is there today for anybody to see, and I blame myself as much as the home’s owner, simply because I could not re-start the negotiations that could have saved all of Fleetwood. In the end, it is a fact that good intentions do not trump the reality that spiteful arrogance does often carry the day.

So one day–after my Battle of Brandy Station book manuscript is finally published–I will write a long, truthful account of what we achieved at Brandy Station–and that which we lost.

In the end, thanks to CWPT and BSF, we have saved much of the battlefield for future generations, and I am here today informing you that more acreage will soon be secured at Brandy Station. The preservation of this momentous battlefield is my life’s work, and this labor will not cease until I am finally placed in the ground next to my dear, darling wife, Deborah Whittier Fitts–also a devoted champion of America’s greatest cavalry battlefield.

But also in the end, we should utter the harsh truth, as much as it hurts to admit it: The southern terminus of Fleetwood–the most important geographical icon at Brandy Station–is now forevermore “lost to history.”

And don’t let anybody else tell you otherwise.

Veritas

There are lessons to be learned, particularly when ego gets in the way of accomplishing an overarching objective. Here, the overarching objective was the preservation of the southern–and most visible–portion of Fleetwood Hill, and its loss is a real tragedy. Let us hope that by bringing these issues to the forefront, we can have a dialogue about them, learn those lessons, and hope that we can prevent something like this from happening again in the future.

Scridb filterMy friend Clark “Bud” Hall wrote the following piece for his former column that appeared in the Culpeper Star-Exponent newspaper:

Fleetwood Hill: The Famous Plateau

“The Most Marched Upon, Camped Upon, Fought Upon, Fought Over Piece of Real Estate in American History.”

As one enters Culpeper County on U.S. Highway 29 from the northeast, your vehicle proceeds about four miles and soon passes a little knoll on the right. Scooped from the flood plain of the Rappahannock River, this grassy, gentle hillock marks the southern terminus of a two and a half mile ridge that witnessed more fighting, more often, than any other piece of ground in this country—in any war.

Fleetwood Hill—geologically the beach of a primeval sea—overlooks a broad, flat, Triassic plateau that sweeps all the way to the river. “This hill commands the finest country for cavalry fighting I ever saw or fought upon,” avowed an experienced colonel.

A military commander bent on advancing his troops for attack toward Culpeper Court House from Fauquier must first ford the Rappahannock and then deploy his command on a broad front as he moves for attack. Unfortunately for the would-be attacker, this is the precise point where a serious obstacle presents itself because the aggressor soon learns (the hard way) his advance is threatened by artillery, infantry and flanking cavalry on Fleetwood Hill to his front.

A Confederate staff officer described the attacker’s dilemma: “This hill commanded the level country toward the Rappahannock and a force…must either carry the position or turn it.” A Southern horseman—he a son of Culpeper—also observed, “There was no movement of troops across the borders of Culpeper that artillery did not blaze from its summits and charging squadrons, on its slopes and around its base, did not contend for supremacy.”

Immortally characterizing Fleetwood Hill as “the famous plateau,” Jeb Stuart’s Chief of Staff penned colorful accounts of the Battle of Brandy Station. This huge cavalry action was highlighted by massive, decisive charges, concluding finally when Federal attackers were driven off Fleetwood on June 9, 1863. In fact, there were 21 separate military actions on Fleetwood Hill during the Civil War—far more than any other battle venue in this country.

Increasing its strategic import for military commanders, Fleetwood hovers above the village of Brandy Station, just a half mile away. Significantly, the ridge—and artillery thereupon—overlooks five converging road junctions in the hamlet. (An early name for the village was in fact “Crossroads.”) Of further consequence, the vital Orange & Alexandria Railroad sliced past the southern base of the hill and the village was a transport station.

The famous Carolina Road (Rt. 685), the major north-south thoroughfare of the Colonial and Civil War eras, bisects the southern terminus of the ridge—a roadway utilized dozens of times by both marching armies to shift artillery and wagons. For the convenience of passing or camping troops, “a remarkable spring,” Herring’s Spring, flowed strong and clear from the base of the hill on the north side (still does) and Flat Run marks the bottom of the southern slope.

During the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac in 1863-1864, the entirety of the length of Fleetwood was used as a well-drained camping platform by thousands of troops. Gen. George Meade selected a spur of Fleetwood as his headquarters site and it is on Fleetwood that Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Gen. Meade planned the Overland Campaign.

So the next time you are headed out on Highway 29 past Brandy Station, kindly glance up at the little knoll just west of the road and note that this unpretentious little ridge has seen more military action than any other piece of ground in American history. And you will also then smugly conclude that “Fleetwood Hill: The Famous Plateau,” provides yet another momentous historical distinction for our own Culpeper County.

Bud’s point is well-taken. There is probably no other piece of ground anywhere in North America that saw more determined fighting than did Fleetwood Hill, which was the site of FOUR different major cavalry battles between August 1862 and October 1863, and which also served as a major portion of the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac during the winter of 1863-64.

Bud will be contributing more regarding the failure to preserve Fleetwood Hill and the McMansion that blights that historic ground today. Stay tuned. Thanks to Craig Swain for the picture of that hideous McMansion, which ruins the sight lines on the hill.

The following article appeared in today’s edition of the New York Times:

Civil War Fires Up Literary Shootout

By MICHAEL CIEPLY

Published: July 29, 2009

LOS ANGELES — History repeats itself. But sometimes it needs a little polishing up from Hollywood.Over the last few weeks, the writers of a pair of Civil War-era histories about the anti-Confederate inhabitants of Jones County, Miss., have been trading barbs in an unusual public spat. It began when the author of one book, rights to which had been sold to Universal Pictures and the filmmaker Gary Ross, discovered that Mr. Ross had spurred the publication of a new and somewhat sexier work on the same subject.

The encounter has created unexpected bad blood over incidents that occurred — or not — more than 100 years ago. And it offers a glimpse of the way that show business and its values have become entwined with the academic book world and its decision-making process.

On June 23 Doubleday published “The State of Jones: The Small Southern County That Seceded From the Confederacy,” a narrative history by the Harvard scholar John Stauffer and the Washington Post writer Sally Jenkins. The book, which on Monday was ranked No. 83 on Amazon’s best-seller list, presented Newton Knight, the leader of the renegade county, as a morally driven hero in the mold of John Brown — but whose appeal was enhanced by his romance with an ex-slave who, in the book’s account, became the love of his life as relations with his white wife cooled.

In the book’s acknowledgments, the authors thanked Mr. Ross, who they said had brought the idea to their editor, Phyllis Grann at Doubleday, and whose screenplay had served as “our impetus and our inspiration.”

This all came as a surprise to Victoria Bynum, a history professor at Texas State University, San Marcos. Her own book on the subject —“The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War” — had been published eight years earlier by the University of North Carolina Press, which sold the film rights to Universal as material for Mr. Ross’s project in 2007.

On June 27 Ms. Bynum got a copy of the new book. The next day, in an e-mail message to academic friends and colleagues at universities across the country, she wrote: “I am appalled at the manner in which these authors have written what is touted as a scholarly work. I am also deeply hurt by the manner in which they have appropriated, then denigrated, my work.”

In a three-part review posted on the Renegade South blog, renegadesouth.wordpress.com, Ms. Bynum lit into the Doubleday book. She particularly objected to what she saw as the new book’s tendency to romanticize Mr. Knight and his love life, its insistence on the idea that Jones County actually seceded and its attempt to place Mr. Knight at the Battle of Vicksburg — touches that do not hurt the story’s cinematic potential.

“If they had said this was a historical novel, I could understand it,” Ms. Bynum said in a telephone interview this week, referring specifically to the portrayal of Mr. Knight’s relationship with his mistress, Rachel Knight. Ms. Bynum, in her review, pointed to evidence that what she called Mr. Knight’s “philandering” also led him to father four or more children by Rachel’s own daughter.

Mr. Stauffer and Ms. Jenkins struck back. In a detailed defense of their research, also posted on Renegade South, they concluded that “Bynum sees scholarship as a form of turf warfare, with only one valid interpretation of the past, which effectively renders history useless.”

Speaking by phone this week, Ms. Jenkins strongly challenged any notion that she and Mr. Stauffer had written their narrative to match the beats of a screenplay that was already written by Mr. Ross, based on extensive research by himself, Mr. Stauffer and others.

“That the genesis of the book was a Gary Ross movie project shouldn’t disqualify it as history,” Ms. Jenkins said.

Speaking separately, Mr. Stauffer said his job from the beginning had been to keep the screenplay as real as possible. “Gary wanted the story for the screenplay to be grounded in the past,” said Mr. Stauffer, who has also written books on abolitionists and a twin biography of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. “Even though the screenplay is fiction, does it ring true to the past?” he said of his mission.

Ms. Bynum did not claim plagiarism, as her work was openly cited in the book by Ms. Jenkins and Mr. Stauffer, but criticized only the way that it had been used. Still, the new history’s origins were unconventional, even in an era when Hollywood producers and screenwriters routinely gin up a graphic novel or write a piece of fiction as bait for a planned script. (The producer Lionel Wigram joined with the artist John Watkiss in creating a Sherlock Holmes comic that laid groundwork for the “Sherlock Holmes” film due from Warner Brothers on Christmas Day, with Robert Downey Jr. in the lead.)

David Paletz, a professor of political science at Duke University, pointed out that run-ins between Hollywood and the academy are nothing new. In “The Bad and the Beautiful,” a melodrama about the film world released in 1953, one of the lead characters, played by Dick Powell, was a college professor who found trouble when he tried to adapt his own hit book for the screen.

What has changed, Mr. Paletz said, is that the Internet has made the current dispute instantly public. “Without the Internet, where does she go?” Mr. Paletz said of Ms. Bynum and her objections. “Maybe she writes a letter to a historical journal.”

According to Mr. Ross, who spoke by phone this week, “The State of Jones” was actually born from lunch-time table talk between Ms. Grann, the editor, and Kathleen Kennedy, a producer with whom Mr. Ross had worked on “Seabiscuit,” which he wrote, directed and helped to produce in 2003.

By Mr. Ross’s account, Ms. Kennedy told Ms. Grann of his plans for Newton Knight, around whom he was trying to build a movie even before he acquired Ms. Bynum’s book in a deal with two less-seasoned producers, Bruce Nachbar and T. G. Herrington, who had already optioned it for film.

Ms. Grann saw potential for a more popular book in all the work that had already been done for the script. So Mr. Stauffer, one of several scholars with whom Mr. Ross had been in touch, wrote the proposal and offered to add Mr. Ross’s name to the project as a co-author, Mr. Ross said.

Mr. Ross declined. Ms. Grann then recruited Ms. Jenkins, a writer with whom she had worked in the past — and whose book about Lance Armstrong, “It’s Not About the Bike,” is being adapted for the screen by Ms. Kennedy and her producing partner Frank Marshall, with script work by Mr. Ross.

So “The State of Jones” was born with a near-perfect Hollywood pedigree — though no one is prepared to shoot the movie. Hollywood has been wary of period dramas since pictures like Universal’s “Frost/Nixon” and the Paramount film “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” did better on the awards circuit than at the box office last year.

(Oddly enough, Universal has already made a version of this story: Its “Tap Roots,” released in 1948, included a fictionalized account of the events in Jones County.)

A Doubleday spokesman, Todd Doughty, said Ms. Grann was on vacation and not available for an interview.

“Why wouldn’t I want another book written about Newt Knight, especially a potentially popular one?” Mr. Ross, who holds film rights to the new book, said of the go-round. “Why would I discourage that?”

At the moment, Mr. Ross is working on the script for “Spider-Man 4.” But he would like to get back to Mr. Knight.

“I hope and I pray the time comes again when people can make serious period movies in Hollywood,” he said.

Prof. Bynum’s review of the new book may be found here. Prof. Stauffer and Ms. Jenkins responded on Kevin Levin’s blog.

This is an ugly, ugly spat. We have enough competition and unpleasantness in the world of Civil War history that we don’t need to be at each other’s throats. I understand both sides of this situation, and deeply regret that this had to happen, because we certainly don’t need to be airing our collective dirty laundry in public. Now that it’s hit the New York Times, there’s no turning back.

I can only hope that Profs. Bynum and Stauffer, and Ms. Jenkins can find a way to make peace amongst themselves.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like