Month:

August, 2008

Susan and I attended the Wings of Victory Air Show, hosted by the Historical Aircraft Squadron, at the Fairfield County Airport in Lancaster, Ohio today. The show featured the F-16 East Coast Demo Team, the actual restored B-17 bomber that was featured in the movie Memphis Belle, a B-25, a P-51 Mustang, the Screamin’ Rebels, which is a group of six restored World War II T-6 trainers, a Korean War-era MiG-17 fighter, and some fun aerobatics and a wing walker (talk about crazy…..).

One of the other highlights was the presence of two of Ohio’s surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen. I had my picture taken with two of them at the Gathering of Mustangs and Legends last year, and it was a great thrill for me. Two more were there today, and it was great to meet two men who gave so much and who had such a magnificent record of achievement during World War II as these men had.

I just love this kind of stuff. I’m like a little boy at air shows–wide-eyed, gawking, endlessly fascinated. And, for a small county air show, not bad at all. It wasn’t like the Gathering of Mustangs and Legends that we attended last October, but what could be? It was well-done, and very well-attended. The weather was spectacular, and I’m very glad we went.

Unfortunately, we forgot the good digital camera, so Susan had to work with the 1.3 megapixel camera in her cell phone. Not ideal, but with the gorgeous weather, it worked out okay. Here are the best photos.

I wish I could understand why there were Civil War reenactors, including an artillery piece, present, but there were. And, I must say, they were some of the farbiest reenactors I have ever seen, and I’ve seen my share of farbs in my day. But, at least we have a tie-in to the Civil War. 🙂

This is the Mitchell B-25 bomber, just before it took off to fly home to Urbana, Ohio, where its owner keeps it. The group of warbird enthusiasts there is working on restoring a B-17 to flying condition.

The highlight of the day was a Heritage Flight by a P-51 Mustang and an F-16. It was an incredibly moving thing to see. Here’s a view of it. These two graceful fighter planes represent the best that the U. S. Air Force has to offer, and it’s quite a sight to see them flying together in formation.

Another view of the Heritage Flight. It’s called a heritage flight because it combines fifty years of Air Force history with two of the finest warbirds ever built.

The Screamin’ Rebels in formation.

And again.

The Screamin’ Rebels making a pass over the runway. It was a very impressive thing to see.

I was lucky. My hometown of Reading, Pennsylvania had a fabulous air show that I attended regularly as a boy. I’m quite certain that it’s the reason why I love them so much to this day and why I try not to miss them when I can help it. These old warbirds are beautiful, and it’s great to see that they’re not only still cared for, but that they can still fly and do the things that made them great in the first place.

Scridb filterJ.D, Mike Nugent and I have all agreed to participate in a seminar on the Battle of Monterey Pass being conducted by the Monterey Pass Battlefield Association on November 8, 2008. Other participants include Kent Masterson Brown, Ted Alexander, and John Miller, the authority on all things Emmitsburg in the Civil War. All proceeds of the program go to benefit the MPBA, which is working hard to preserve land and add interpretation to the battlefield at Blue Ridge Summit, which marks the largest engagement fought in Franklin County, Pennsylvania during the Civil War. Please come check it out.

Scridb filterFor the second time, John Maass has decided to pull the plug on his excellent blog, A Student of History, which has long been one of my favorite blogs. I understand the time constraints he faces and will miss the blog. Goodbye and good luck, John.

I’ve deleted the link to his blog, but will gladly restore it once more if John gets back into the game.

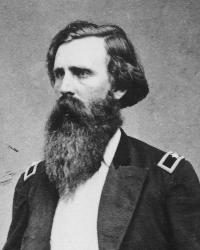

Scridb filterTime for another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten cavalrymen….

Andrew Jonathan Alexander was born to a wealthy and influential family in Woodford County, Kentucky on November 21, 1833. He was one of six children; one of his sisters married Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair, the influential Missouri Congressman. His father died in a mill accident on the family estate, and his mother went blind. Opposed to slavery, Mrs. Alexander freed her slaves and settled in St. Louis. Andrew attended Centre College in Danville, Kentucky and then returned to St. Louis, where he was engaged in business pursuits when war came in the spring of 1861.

Andrew Jonathan Alexander was born to a wealthy and influential family in Woodford County, Kentucky on November 21, 1833. He was one of six children; one of his sisters married Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair, the influential Missouri Congressman. His father died in a mill accident on the family estate, and his mother went blind. Opposed to slavery, Mrs. Alexander freed her slaves and settled in St. Louis. Andrew attended Centre College in Danville, Kentucky and then returned to St. Louis, where he was engaged in business pursuits when war came in the spring of 1861.

He was commissioned in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles as a second lieutenant on July 26, 1861. He was immediately promoted to first lieutenant the same day. The new lieutenant was assigned to serve on the staff of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, where he impressed the general with his efficiency. Alexander was appointed assistant adjutant general, serving first with McClellan, and later with Maj. Gen. George Stoneman.

He received brevets for gallantry for the 1862 Peninsula Campaign for carrying messages from McClellan to and from Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman under fire and for leading various scouting expeditions with the Union cavalry, for performing outstanding scouting and reconnaissance services before and during the Battle of Gettysburg, the Atlanta Campaign, and other engagements, eventually receiving a brevet to brigadier general of volunteers, dated March 13, 1865.

Originally assigned to the staff of Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, he joined Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s staff as assistant adjutant general of the Cavalry Corps when Stoneman took medical leave after the Battle of Chancellorsville. At the end of July, 1863, Stoneman became the first commander of the newly-formed Cavalry Bureau, an organization intended to provide remounts for the Union cavalry forces. Alexander went with him, serving on Stoneman’s staff at the Cavalry Bureau. On September 13, 1863, he was promoted to captain in the 3rd U. S. Cavalry (the successor designation of the Regiment of Mounted Rifles).

When John Buford contracted the typhoid fever that claimed his life, he went to Washington to recuperate, staying in Stoneman’s rented home. On December 16, 1863, the day Buford died, Alexander brought him a long-coveted prize: a major general’s commission. Buford, who was in and out of lucidity as the end drew near, had a lucid moment and said, “Too late. Now I wish I could live.” Alexander helped his fellow Kentuckian sign the commission.

In the spring of 1864, Stoneman was assigned to take command of a division of cavalry attached to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army. When Stoneman left, Alexander stayed on, joining the staff of his successor, Brig. Gen. James Harrison Wilson. Later that spring, Wilson assumed command of the 3rd Division, Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac, and Alexander went to join Stoneman’s staff once again. He served on Stoneman’s staff with Capt. Myles W. Keogh, a dashing Irish soldier of fortune who had loyally served Brig. Gen. John Buford until the dragoon’s untimely death on December 16, 1863. Alexander and Keogh developed a very close and lasting friendship that lasted until Keogh’s untimely death at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876 (Keogh and Alexander rest in the same cemetery in Auburn, NY). Alexander married Evelina Throup Martin on Nov. 3, 1864.

When Alexander returned to the army after his wedding, he joined Wilson’s staff as his chief of staff. Wilson, nominally Sherman’s chief of cavalry, was in the process of assembling a 15,000 man all-cavalry army that became a mounted juggernaut that served as the prototype for modern armored cavalry. Alexander performed especially valuable service in rounding up sufficient quality mounts for Wilson’s new army. Wilson urged Alexander’s promotion to full brigadier general of volunteers, but the war ended before that recommendation could be acted upon. However, he was brevetted colonel in the Regular Army by Grant.

On July 28, 1866, he was appointed senior major of the newly-formed 8th U. S. Cavalry and settled with his family at Camp McDowell, Arizona, where he and his wife had their first child, Emily. Commanding the Subdistrict of the Verde, Alexander scouted regularly against Apache Indians with the cooperation of the Pima Indians. He also contended with fights among residents of of nearby settlements.

In 1869, he was reassigned, commanding Camp Toll Gate until February 1870, when he went on leave. He rejoined the regiment in New Mexico. While commanding Fort Bayard in 1871, he was ordered to Fort Garland, Colorado at the direction of Sec. of War Belknap. He took leave in 1872 to tend to his ill wife after she had a miscarriage and then returned to duty in 1872, when he reported back to Fort Garland.

He was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 2nd Cavalry on March 20, 1879. In 1883, he began suffering serious health problems, including malaria, diabetes, and rheumatism. In 1884, he developed a bad inner ear infection and was retired as a full colonel as being unfit for further duty, effective July 3, 1885. His friends (including Generals Sherman and Stoneman) tried to arrange for him to be appointed deputy commander of the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C., but his health was too poor to permit him to perform the duties associated with the job. He spent much of his retirement writing about his war-time experiences and in maintaining a regular correspondence with Wilson, with whom he became close friends.

On May 4, 1887, while on a railroad train with his wife on their way to their home near Auburn, New York, he died suddenly and unexpectedly. He was a mere 54 years old. Alexander was buried in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, joining his dear friend Keogh there.

Maj. Gen. James Harrison Wilson wrote of him, “Those who had the fortune to know him during the war will readily recall and bear witness to his superb figure, his stately carriage, his bright, flashing blue eyes, his flowing beard as tawny as a lion’s mane, his splendid shoulders, his almost unequalled horsemanship…Standing over six feet in height, he was trim and commanding a figure as it was ever my good fortune to behold.”

Here’s to A. J. Alexander, a forgotten cavalryman who gave good service to his country both during the Civil War and in the years afterward.

Scridb filterThree of my friends, including Mike Peters, from our CWRT, and I spent the day touring the battlefield at Perryville yesterday. I’d only been there once before, in 1994 or 1995, and Mike likewise had only been there once before. Tim was making his first visit, while Rory, our fourth, has been there multiple times. As you will see from the photographs, it was an absolutely magnificent day–lots of sun, blue skies, no humidity, gentle breezes, and about 80 degree temperatures. One could not have asked for any better weather for battlefield stomping.

The last time that I was there, there was only a fraction of the interpretation that’s present now, and thanks to the efforts of the CWPT, lots of land has been added to the park. It is important to note that the battlefield is a Kentucky state park, NOT a national park. Nevertheless, it’s gorgeous, mostly pristine, and has tons of interpretive markers and trails. There are, in fact, more interpretive markers on this battlefield than there are on a lot of the national parks, and I was really impressed by it.

Imagine a battlefield as rural and pristine as Antietam, about the same size, only without all of the monumentation that marks Antietam, and you have Perryville. The battlefield is narrow and very compact; there are places where opposing batteries were blasting away at each other from within cannister range. The battle was one for ridge line after ridge line; the ground undulates and is marked by one ridge after another.

There’s also a nice little visitor center with a decent selection of Western Theater books and some other trinkets (I added another pin to the collection on my CWPT hat), and a small museum with some well-presented exhibits.

We were fortunate enough to have a couple of West Point alums who are retired Regular Army officers with us for a a couple of hours, meaning we were able to get onto some private property and see some sites associated with the battle that we otherwise would not have seen, including the site where Sheridan disobeyed orders and brought on the battle. That was extremely helpful to helping us to understand how things proceeded once fighting broke out.

We easily walked 8 or 9 miles over some extremely hilly, undulating terrain. It was tiring, but we saw pretty much the entire battlefield. I came away from it with a much better understanding of this battle and how it developed and played out. I am going to re-read Ken Noe’s excellent history of the battle, and then I should really have a solid understanding of it.

This beautiful battlefield, with its gorgeous hills and dales and lovely views, could easily and rapidly become one of my very favorites. You can also easily see the entire battlefield in a single day, which is nice. It’s compact and accessible, and I highly recommend a visit.

A lovely view from Peters Hill, which was Phil Sheridan’s headquarters during the battle. The view in the distance is of the main battlefield. This is the position from where Sheridan gave the orders that brought on a general engagement in violation of his orders.

Our group, at Parsons’ Battery. From left to right: Tim Maurice, Mike Peters, Rory McIntyre, Clair Conzelman, Tasha Conzelman, and yours truly.

Starkweather’s Hill, from Parsons Battery. This was the highest point on the Union line, a position from which the Union troops were driven.

The monument to the Union soldiers on the battlefield near the Confederate cemetery.

The Union order of battle monument.

The monument in the Confederate cemetery. This is a mass grave with only two specific soldiers identified with their own headstones. The rest are apparently unidentified.

The Dye house, which served as Simon Bolivar Buckner’s headquarters during the battle.

Looking down on the Squire Bottom house from the main Union line.

A full shot of the Squire Bottom house. Bottom lost everything as a result of the day when the war visited his property.

This is a recent addition to the battlefield honoring Michigan’s contributions to the Battle of Perryville. It overlooks the Squire Bottom house.

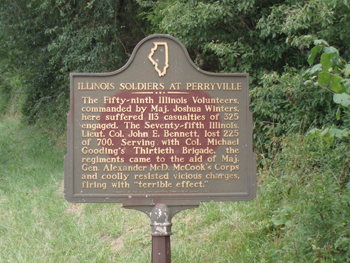

A similar marker honoring Illinois’ contributions to the Battle of Perryville. This is located very near the final Union line, at the Dixville Crossroads.

We encountered this cheeky llama at the end of the day, near the position that marked the final Union line of battle near the Davidson house. We determined that he is the sole surviving member of the 143rd Peruvian Llama Cavalry. 🙂

Scridb filterThe following article appears today on CNET. The speech that it discusses was given at a major cybersecurity conference going on in Las Vegas called Black Hat:

August 7, 2008 11:06 AM PDT

Cybersecurity lessons from the Civil War

Posted by Elinor MillsLAS VEGAS–The security issues we face today in cyberspace are the same ones the country faced during the American Civil War when Abe Lincoln was relying on telegraph transmissions to help keep the country united, a top U.S. cybersecurity official said in a keynote speech at the Black Hat security conference here Thursday.

Abe Lincoln, “the first wired president,” Beckstrom says. Lincoln was obsessed with reading telegrams that delivered updates from the battlefield, using them to learn about the military strategies and to offer feedback, said Rod Beckstrom, director of the National Cyber Security Center in the Department of Homeland Security.

“If he were alive today we would probably call him an e-mail junkie or a cyber junkie,” he said. “He was the first wired president; (telegraph) was a fixed wire” that could be severed or tapped.

Security lessons from battle were available even earlier in American history, according to Beckstrom. In the French and Indian wars, British forces relied on traditional warfare formations and often got slaughtered by French frontiersmen and their Native American supporters, who used guerrilla tactics like roadside ambushes.

One officer fighting on the side of the British who survived such attacks–George Washington–took the lessons of flexible fighting and guerrilla warfare with him in fighting for American independence, he said.

Even that American revolutionary war was almost lost because of “one of greatest threats we face today in cyberspace”–insider threats and hackers, Beckstrom said, displaying a portrait of Benedict Arnold, a disgruntled commanding officer who was passed over for promotion and charged with corruption after facing financial difficulties.

“He saw an opportunity,” and was selling plans for West Point and other military secrets to the British, but was caught in the end, Beckstrom said.

“We have the same threats today, just on different technology and mediums,” Beckstrom said.

Today, however, nations, businesses, and individuals also confront a single point of failure in cyberspace, with the Internet protocols and technologies, like the Domain Name System, he said. (A serious DNS vulnerability was the subject of a session at Black Hat on Wednesday.)

“Invest in protocols because it may be the cheapest security dollars we can invest,” Beckstrom said. The Department of Homeland Security is funding research related to DNS security, among other initiatives, he added. “We’ve got to move forward because we’ve got to change the odds of this game.”

The IP dependencies in the telecommunications sector put emergency communications, like mobile phone texting, at risk, Beckstrom said, noting that he was in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001, and in Pakistan when an earthquake hit and saw firsthand how crucial texting is. A cell phone tower can handle 200 or more calls simultaneously and about 5,000 text messages a second, according to Beckstrom.

And don’t forget the plain old telephone system, which will still be operational if the IP system goes down, he said.

Without elaboration, Beckstrom said: “Why can’t we quarantine computers that are disrupting the Internet?”

He touched on issues of punishment, “cyber justice,” and cyber diplomacy, and ended the talk asking more questions than he answered.

“What are the new cyber rules?” he asked. “How do we develop an international framework and move toward cooperation?”

Lincoln’s proclivities toward the telegraph have been well documented, most recently in a 2007 book titled Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. However, this is the first time that I’ve heard this particular analogy made.

The Civil War still permeates everything we do in this country.

Scridb filterAs I’ve mentioned here previously, I get an e-mail every time a comment is posted to this blog. Pingbacks from other blogs qualify as comments, and I get these regularly. The vast majority of those pingbacks are from splogs (spam blogs) and I immediately delete them as spam. Because of that, I check them carefully when they come in. Today, one came through from an interesting looking new blog. I checked it out and liked what I saw, so I’m adding it to the blog roll.

It’s got the intriguing name of Past in the Present, and it’s maintained by a fellow named Michael Lynch. Here’s how he describes himself: “I’m an East Tennessee native with a master’s degree in U.S. History and an interest in the American Revolution in the South. I’ve done a little college-level teaching, I used to do collections/exhibits at a Lincoln/Civil War museum, and I’m a former executive director at a late-1700’s historic house site.”

Welcome aboard, Michael. I’ve added a link from my blog roll.

Scridb filterThe following review of the new visitor center at Gettysburg by publisher Pete Jorgensen appeared in the most recent issue of the Civil War News:

The new Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park is not a museum at all and it has little on display regarding the battles of July 1, 2 and 3 in 1863.

It is a massive, attractively designed structure with vast amounts of exhibit space devoted not to exhibits, but to presentations. It also has a large gift shop operated by Event Network, a for-profit cultural attraction retailer.

The museum/visitor center is owned by a private, non-profit foundation which has engaged the National Park Service as groundskeepers, guides and guardians of the country’s largest collection of Civil War artifacts, which are stored away, far out of the visitor’s view.

Just before the “museum” opened, Gettysburg National Park Superintendent John Latschar tried to excuse the lack of exhibits and the identification of artifacts by saying of the old visitor center, “What we’ve got here right now is what is known as a collections museum. We’ve got rows and rows of rifles and pistols and cases full of battle debris, and zero story.”

He explained, “What we’re creating is a storyline museum, where you use artifacts to illustrate the storyline. So we have no need for 40 varieties of rifle muskets. We’re trying to provide our visitors with a basic understanding of the battle of Gettysburg in the context of the war and in the context of America….”

For 10 years people who have been involved in this project argued that the reason for building a new museum was that they had storage rooms full of more than 38,000 artifacts from the famous Rosensteel Collection and no room to display them.

Now that they have the room, they still have no interest in displaying them. We’d call this “museum fraud.”

This collection was started by John Rosensteel of Gettysburg who was age 16 in July 1863. In the 1890s he opened the Round Top Museum to display his collection to visitors. He expanded his collection by purchasing others and bought from local residents who had barns full of stuff from the battlefield.

In 1921, his nephew George Rosensteel opened the Gettysburg National Museum on land purchased from his uncle and continued buying up other Civil War artifact collections. His museum remained in private hands until 1971 when it was donated to the National Park Service.

At the former visitor center — the Rosensteel museum building — the Park Service displayed 6,633 artifacts from the Rosensteel collection. In April, when the new visitor center opened, only 1,338 artifacts were put on display, according to a Park Service news release.

That’s 79.8 percent fewer objects now exhibited than during the 37 years the Park Service has been responsible for the collection. It’s only 3.5 percent of the total artifacts locked away in storage.

We don’t even have to go to the definition of what the word “is” really “is” to unravel this outright fraud. Just pick up the dictionary — any dictionary — and look up the definition of the word “museum.”

You won’t find any definition for a “storyline museum,” nor will you find that a museum is “a place where stories are told.” No. That’s under “theater.”

The universally recognized arbiter of the language is the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary. It states: museum.n, A building or institution in which objects of historical, scientific, artistic, or cultural interest are preserved and exhibited. Also: the collection of objects held by such an institution. ?

There is no secondary definition of the word “museum.”

Gettysburg park officials apparently don’t know or don’t care what a museum is or what the general public expects to find in a museum. They built a “theater” to tell a “storyline” and now are trying to convince us that it is a new kind of museum that people who write dictionaries don’t know about yet.

Since this so-called museum isn’t designed to exhibit the 38,000 plus artifacts in storage at Gettysburg National Park, why keep them hidden? Why keep them at all? Let’s have an auction so that the people who value these objects can acquire them at market price.

What purpose is served by locking up thousands and thousands of Civil War muskets, rifles, carbines, shells, belt plates, uniforms, buttons, and all sorts of other stuff? Always the excuse has been “we don’t have the room to display it.” But now that they have the room, they won’t display it and we doubt many in the Gettysburg Park management can correctly identify any five objects in the collection selected at random.

That’s their problem, but it is our problem too. It’s a problem for the American taxpayer and the public in general. It’s a problem for the thousands of school kids who visit Gettysburg each year and the tens of thousands of visitors who think they will see some of the old guns, uniforms, bullets, cannon projectiles and other artifacts left behind after the battle. These are the things they expect to find in a museum.

We suspect park managers don’t know what they have, so they don’t know what is important to put on display and what is not.

For example, Gettysburg National Military Park has the best collection of Confederate 12-pounder bronze Napoleon cannon in the country. But not a single Confederate bronze Napoleon is on display in the “museum.”

All the Union 12-pounder Napoleon cannon look the same from a distance, regardless of maker, as all were made to a set of standard specifications. But there are five types of bronze Confederate Napoleons, all with distinct profiles.

On the field at Gettysburg you can pick out a Macon Arsenal Napoleon from 200 yards away, but you have to get closer to positively identify many others. Confederate Napoleons were made at Augusta Arsenal, Macon Arsenal and Columbus Arsenal in Georgia. And at the Tredegar Foundry in Richmond, Va., at Leeds & Company in New Orleans, at Quinby & Robinson Foundry in Tennessee and at a small cannon works in Charleston, S.C.

All of these represent different scientific and historical views on cannon design and economy of materials in the 19th century. That’s stuff you go to a museum to study and see first hand.

The first case in the museum’s display area contains a mixture of 26 Union and Confederate field artillery projectiles. None are identified. You’d never know which ones were used by which side or that each one actually does have a name, type and size associated with it.

Shells, solid shot, canister rounds, case shot, rifled and smoothbore ammunition are all mixed together. To everybody except a projectile collector the case is just a pile of old iron. And that apparently includes the National Park Service museum curatorial staff.

There are four more cases with 93 artifacts identified only as Civil War Firearms. But, again, there are no individual identifications as to Union or Confederate, carbine, rifle, or musket. One of these cases has 44 “pistols,” many of which are actually revolvers, not pistols. Each, of course, had a model, maker, type name, bore size and intended use, but there is no signage to tell anybody that.

A careful review of all 93 firearms confirms that nobody on the National Park Service staff knows anything about Civil War firearms and, worse, they don’t care if you do either.

One model infantry arm was ubiquitous during the four years of war — the Model 1861 Springfield Musket. They were everywhere. They were used in every major Civil War battle, carried for four years by half the Union army and they were also fired in hundreds of skirmishes between the forces of North and South.

Springfield Armory itself turned out more than 265,000 Model 1861 rifle muskets and 21 private contractors produced another 452,000 to the same government specifications.

In total, of the 1.5-million Union infantry rifle muskets produced, 717,000 were Model 1861 Springfields.

The number on display among the 93 firearms in the Gettysburg Museum’s display lobby: Zero.

That’s right. Zero. We counted and examined the cases three times.

Zero Model 1861 rifle muskets.

It’s like a man in charge said, “Hey, Jim, go down to the basement and get some guns to fill up those display cases.” And Jim said, “Which ones do you want, John?” And the reply could have only been, “Long ones, medium ones, short ones — mix ‘em up to get a good representative sample.”

It’s not only incredible, it’s ironic.

This place claims to be the Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park, and as a museum it can’t find the space to display a single example of the one model of rifle musket that was used by nearly half the Union infantry.

According to the Gettysburg Foundation’s Web site, the following was listed as the primary goal of the new building:

“Protection of the park’s collection of artifacts and archives: The park owns collections of 38,000 artifacts and 350,000 printed texts, historic photographs and other archival documents. New facilities are needed to provide appropriate storage conditions, proper care, and display of the collections.”

Well, there is no question they haven’t met their goal when it comes to the part about “display of the collections.”

Another case along the walls contains buckles, saber belt plates and buttons. There is one standard U.S. officer’s saber belt plate, one General Officer’s 3-piece wreath plate with stippled gold-leaf plating, but not a single one of the common enlisted cavalryman’s or artilleryman’s plate with a two- or three-piece silver leaf design surmounting a brass eagle.

Actually, there might be an example of the most common saber belt plate of the Union Army but it is hard to tell. In one glass case there is a field dug, tarnished and corroded belt plate that’s nearly impossible to identify. You just can’t see which applied silver leaf design it may have had, if any.

And one more — just one more — example. The oval Confederate brass enlistedman’s belt plate with a surmounted five-point star, and identified in Steve Mullinax’s book Confederate Belt Buckles & Plates on page 164 as Plate No. 299, is one of the few artifacts in the display cases with a little identification sign. It reads, “Union Militia Belt Plate” GETT #28220.

Mullinax, known for years as the country’s most informed expert on Confederate belt plates, must be wrong. The Gettysburg Museum of the American Civil War (its official name), managed by the National Park Service, apparently knows more about Confederate belt plates than the guy who wrote the book. But if Mullinax is right, that plate is worth $3,000 today and nobody will ever know it.

Just where does one go to study an exhibition of objects having scientific and historical value? All dictionaries say these objects are to be found in a “museum.” But not at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum.

There you will be charged $8 to see a film entitled “A New Birth of Freedom” that is full of its own errors, and you’ll walk through corridors with mannequins wearing reproduction uniforms, sitting on plaster horses. Then you’ll see some short film clips of the battle as you pass from room to room enjoying the “visitor experience.”

Soon, you’ll arrive at the Bookstore, Gift Shop and Refreshment Saloon, primed to open your wallet again to capture the flavor of the Civil War and perhaps your own stuffed soldier.

It is really unfortunate that those entrusted with the acquisition, conservation, study, exhibition and educational interpretation of objects having historical value have no clue as to their public responsibilities.

They are running a theater, not a museum. And they are public employees whose salaries and benefits are paid by your tax dollars.

If these new facilities were built for theater, the public should start demanding that the nation’s largest publicly owned collection of Civil War artifacts be sold — or that a museum be built to house, conserve, study, exhibit and interpret them.

Yes. A museum. Build a museum. What a novel idea.

In fairness, it should be noted that Pete visited before the identification tags were placed on the artifacts in the exhibits. They are now properly identified.

I happen to agree with Pete’s assessment of the place. I find it a real tragedy that the massive Rosensteel collection will probably never be seen in anything close to its full glory ever again. Sure, the artifacts are preserved, but so what? If nobody sees them or even knows they exist, what good are they?

All of the extraneous stuff in the museum is nice, but I would rather see the artifacts from the battle rather than a comprehensive narrative of the Civil War. Leave that to the new museum at Tredegar, or the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Instead, let’s focus the Visitor Center on Gettysburg.

Scridb filterThe following article appeared in last Friday’s edition of the Hanover Evening Sun newspaper, about how the new Gettysburg Visitor Center–of which I am not a fan–is harming the businesses that line Steinwehr Avenue:

Steinwehr business: Gettysburg visitor center move hurts strip

By ERIN JAMES

Evening Sun Reporter

Article Launched: 08/01/2008 09:36:10 AM EDTGettysburg business leaders are bracing for the potential negative impact of the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center’s recent move away from Steinwehr Avenue by pursuing a revitalization project of the tourist hub.

In fact, that was the premise of a grant application submitted by Main Street Gettysburg to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said USDA spokeswoman Rosemarie Massa.

On Thursday, the federal agency announced it will award $70,000 in grant money to “complete a revitalization plan for the small businesses which will be negatively affected by the relocation,” according to a USDA press release.

Main Street Gettysburg executive director Deb Adamik said the visitor center’s move is not the only reason Steinwehr Avenue is in need of funding, but it is the most obvious, she said.

“You’re taking a base of thousands of visitors farther away,” she said.

Gettysburg officials, headed by Main Street, announced in June that they had secured $215,000 toward the project’s planning phase, but they didn’t specify at the time where the grants were coming from. Adamik said Thursday that the USDA’s $70,000 was included among the original total and that the sources of other grants would announce their own donations at a later time.

The potential for tourists to abandon Steinwehr Avenue as a shopping destination now that the visitor center has moved was vaguely mentioned as a reason for beginning the revitalization project when it was announced in September 2007 and when its status was updated in June. The street is due for a new look and new infrastructure, planners said.

But Massa said the gist of Main Street’s application to the USDA suggests a stronger sentiment among business leaders to address growing concerns about the visitor center’s move.

Fears about declining business on Steinwehr Avenue as a result of the visitor center’s move date back to the project’s planning phase.

At that time, the National Park Service came under attack from residents and business owners concerned the facility would lure tourists away from the downtown area and already established tourist sites along Steinwehr Avenue – just down the street from the visitor center’s original location.

In response, park Superintendent John Latschar said the Park Service was committed to creating a shuttle system to take tourists to the Eisenhower National Historic Site and into Gettysburg. And he said he believed the new facility would encourage visitors to extend their stay and spend more money around town.

Groundbreaking on the new site off of Hunt Avenue and Baltimore Pike commenced in summer 2005, and the visitor center opened April 14 of this year.

But when tourism season kicked off in May, many Steinwehr business owners wouldn’t say whether they expected the visitor center’s move to negatively impact the street. Some even said they felt the potential impact had been overestimated.

At the time, the head of the Steinwehr Avenue Business Alliance said it was “too early to tell.”

But earlier this week, Tom Crist said there’s evidence the original fears were well-founded.

In fact, he attributed this year’s slow business to two reasons – the state of the economy and the opening of the new visitor center.

“(Tourists are) not coming down Steinwehr Avenue right now,” said Crist, who owns Flex and Flanigan’s at 240 Steinwehr Ave.

Adamik said she hasn’t spoken with “too many” business owners yet about the impact so far of the visitor center’s move.

But she suspects the economy is the “overriding issue” in preventing visitors from spending money downtown.

“They just don’t have as much money as they used to as disposable income,” she said.

Contact Erin James at ejames@eveningsun.com.

This doesn’t surprise me a bit. The first time that I saw the junk store in the new VC that masquerades as a book store, I knew it was going to do substantial harm to the local businesses that have drawn on the tourist trade for years.

It’s really no wonder that a lot of the local citizenry hates the battlefield:

* The Park is not always the best neighbor, as evidenced by the harm being done to the local businesses.

* The needlessly large Harley Davidson dealership owned by local blood sucking leech David LeVan brings vast amounts of noise and debauchery to a small town that neither wants nor needs it.

* LeVan, who just doesn’t know when to quit, remains absolutely determined to bring gambling to Adams County in the form of a horse track and slot machine casino, even though his last attempt to do so went down in flames by a large margin at the polls.

* Tourist traffic causes gridlock in the town and makes it impossible to find a parking space or a table in a restaurant at times.

There’s plenty more, but you get the point. While the old VC was long past its prime and had to go, the current thing is not what anyone needed. There will be more to say about that later.

Scridb filterI’ve known for some time that our book One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 was being considered by the History Book Club and the Military Book Club.

Ted Savas has today announced that both book clubs have chosen One Continuous Fight to be offered to their members. This is exciting for a lot of reasons. It means that the book will get a great deal of exposure it might not otherwise have gotten, any books purchased by them are non-returnable (which is a good thing), and only worthy publications are selected by the book clubs. Even though One Continuous Fight has sold well since the moment of its release, this will mean even greater sales.

Another of my books, The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Last Campaign, published in 2006, was also selected by both of the book clubs, and both substantially boosted the sales of the book. And, it’s a very cool thing to see my work featured in the mailers that the book clubs send out each month. It very much says that you’ve made the grade as a historian, and that’s really a gratifying thing.

So, thanks to Ted’s excellent work promoting and selling the books that he publishes, we’re going to be offered by the two book clubs, and I’m very pleased by that. Thanks, Ted.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like