Month:

February, 2006

Kevin Levin responded to yesterday’s post on military history in a social hisstory world. Thanks for reading Kevin, and thanks also for taking the time to formulate a thoughtful response. I wanted to respond to a couple of issues raised by Kevin.

First, Kevin said: “Firstly, I hope Eric has more to say surrounding his comment on Rable’s Fredericksburg study. Given that the book won a number of important scholarly awards from reputable institutions it is hard to take seriously the conclusion that it ‘fails to provide a complete view of either the military or social aspects.'” Here’s the response you asked for, Kevin. Your own point–that it has won scholarly awards from institutions–suggests to me that you’re referring to awards by academic institutions. If so, then it’s just furthering my own point, which is that it’s endemic of academic institutions turning their collective snoots up at military history.

As to the specifics, I am far from the only critic to point out that Rable’s treatment of the military aspects–the battle itself–is secondary to the social aspects of the book and that the discussion of the battle is lacking in detail. See the reviews on Amazon.com if you want examples of what I’m talking about here.

My own preference is for Frank O’Reilly’s excellent book, which provides what I believe is the appropriate degree of social history to place the military aspects into their proper context in a traditional, but very well done, campaign study.

Second, I think you’ve misunderstood me a bit, and in re-reading my post, I must claim responsibility for it. I didn’t express myself as well as I might have liked. What I meant to say is that to the extent that understanding the motivations of the fignting man is necessary and important for me to properly do my work, then social history interests me. Beyond that, however, reading books that constitute purely social history is of no interest to me at all. In point of fact, I find them boring as hell, and gave up trying to read them long ago unless they’re something really exceptional.

As to the issues of race and slavery that fascinate you, I find them much less interesting and much less compelling. While I understand that these issues are there as an underlying current, they are not central to what interests me at all. These issues are clearly critical to understanding HOW things got to the point where brothers shed the blood of their own brothers. I get that. However, my interests fall to the tactical level–my interest really begins with the situation once the armies are met on the field of battle. And there, those issues are not much more than vague underlying themes that have little role in understanding why a commander made a tactical decision and how that tactical decision played out. Those are the issues that interest me.

As to the bigger problem, I don’t necessarily disagree with you. I also think that Andy MacIsaac also makes some excellent points in his discussion of this issue. Andy is right, of course, that to some extent the two disciplines are inseparable and that we need both. That, in turn, brings me back to my original point: why do the academic historians turn their collective snoots up at military history? If Karl von Clausewitz was correct–and I firmly believe he was–in believing that war is politics by other means, then isn’t military history a logical extension of both political science and social history?

And if that’s true, then my original question stands and remains unanswered: why is that the academic historians treat military history as a red-headed stepchild?

Scridb filterAs he so often does, Mark Grimsley’s blog features an especially interesting line of discussion about where the discipline of military history fits into an academic world that treats it like the proverbial red-headed stepchild. The recent trend among academic history seems to be to downplay military history; Mark mentions a request that was posted on an H-Net list by a modern historian who was far from excited about the prospect of his students looking at issues of military history.

Some have tried to cross this gap by doing interdisciplinary work. George Rable’s book on the Fredericksburg Campaign attempts to do this and fails to provide a complete view of either the military or the social aspects. Ed Hagerty tried to turn a regimental history into a social history with his book on the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry, and bored me so terribly that I never was able to finish it.

Finding a way around this problem is a common theme on Mark’s blog, as he struggles to try to help military history find its niche in the overall scheme of the history discipline. Fortunately, I’m not plagued by this particular burden; not being an academic historian permits me to focus solely on those issues that interest me to the exclusion of those that don’t. And, I must admit, as a general statement, social history is a discipline that bears absolutely no interest for me. Genuinely, I couldn’t care less. Issues such as slavery and its consequences, and the consequences for the freedmen simply are of no interest to me. What interests me are the military aspects–the battles, the men who fought them, and their motivations. Social trends mean nothing to me in the big scheme of things, with the lone exception of how they might impact on those aspects that do interest me.

My fellow blogger Kevin Levin, on the other hand, seems to be primarily interested in the social history aspects of the war, with particular focus on the race relations issues. I tip my hat to Kevin–just because those issues hold no interest to me doesn’t mean that they’re not worthy or that Kevin isn’t to be commended for studying them. In fact, they are worthy, and I do commend Kevin for his interest and pursuit of them. That is, as they say, why there are different flavors of ice cream–each can find his or her favorite flavor. My favorite flavor happens NOT to be social history.

It was, for instance, impossible for me to study the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry without looking at the gap between the regiment’s officer corps and its enlisted men, and what dynamic was created by that gap. So, to some extent, I had to look at the social history of Philadelphia to get a better understanding of that. However, that social history is quickly subsumed by my focus on the military aspects of this excellent regiment.

What stuns me about all of this is that there are some really fine military historians who can’t find work in the academic world. My friend Mark Bradley is working on his Ph.D. dissertation. Mark wrote one the best campaign studies I’ve ever seen in his study of Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign and an equally impressive study of the events that led to Johnston’s surrender at Bennett Place in April 1865. His degree will be from a very reputable place, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Yet, Mark is finding it very difficult to find a job. Why? He’s a guy whose primary focus is military history. So, in order to hedge his bets, he’s had to compromise. His dissertation deals with Reconstruction, and his project after that will focus on the Freedmen’s Bureau. He’s doing this to “prove” that he also has the chops to do social history, and thereby make himself hireable.

Now, please don’t get me wrong–I fully understand why Mark’s doing what he’s doing. A job is a job, and Mark needs one. So, he’s doing what he must, and nothing I’m saying here should be construed as a criticism of him. It’s not. I will never criticize someone for doing what he or she has to do for their own survival or advancement. That’s not the issue. The issue, rather, is my befuddlement with why the SYSTEM is forcing him to have to make those choices. Isn’t it time that the academics stop treating military history as a red-headed stepchild and give it the respect it deserves, so that a quality individual like Mark Bradley can focus on what he does best?

What’s wrong with this picture?

Scridb filterI would also be remiss if I didn’t wish all of you a happy Valentine’s Day. So, happy Valentine’s Day to you and yours!

Scridb filterWARNING: Today’s post has absolutely nothing to do with the Civil War.

After three-plus months of inexplicable delays, Susan and I today began our grand adventure.

As I write this, the excavators are finishing up the digging of the hole for the foundation for our new house. The process of building a house is something entirely new for both of us. I grew up in a condo complex, and the house we live in now was built in 1969. Susan grew up in two houses–one more than one hundred years old, and the other more than fifty. Consequently, this whole process is pretty alien to both of us.

We’re building in a very small but rapidly expanding community. Five years ago, it was a small, rural town of perhaps 2000 people with no recent development. However, the inevitable spread of Columbus’ urban sprawl has reached this little town, and in the past several years, there have been at least four large subdivisions begun. Two, including the one we’re building in, are for larger, more expensive homes. One is for mid-sized production homes by a large developer, and the other consists of very small, densely packed houses that I call, not lovingly, “cheeseboxes.” All of this explosive growth–and there WILL be more–strains the infrastructure of this small town, which has only one guy responsible for building permits, plan approvals, and inspections. The poor guy is probably swamped with work most of the time.

Initially, it took forever to get the construction loan approved. Why? We’re building the biggest house in the area in years, and they had a difficult time finding comps to make sure that the value would support the price. This added a month to that process. Foolish me. I assumed–incorrectly–that if I signed a contract to build a house, that was the price, and that was the value of the house. WRONG! In reality, they still do a full appraisal–even before the house is built, based on the plans–to ensure that the house will have sufficient resale value to support the contract price. That was a real eye-opener for me. I had no idea. The thought of appraising something that had not yet been constructed simply never occurred to me.

Then came finalizing plans, etc. They were supposed to dig on February 1. However, the permit guy (see above) was hospitalized, and there was nobody to sign off on the plans and issue the permit. Then, we got bumped back to February 9. No permit yet; it finally issued that day, too late for the work to be done. So, the excavation had to be rescheduled again. They FINALLY commenced digging the hole today.

They tell me it will be six months from today to closing, plus or minus two weeks. We have a LOT to do between now and then to get the existing house ready to sell and to unclutter our very cluttered lives. We will keep everyone posted.

However, for now, it’s a bold new world, and one I’ve never visited previously. To say that it will be an adventure is an understatement…..

Scridb filterThis post is related to my last post on the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

For a long time, I’ve been a bit embarrassed by just how little I knew about the Spanish-American War, so I made a conscious choice to change that after Susan and I visited Key West in October 2003. I made a point of seeking out and finding the memorial to the dead sailors of the U.S.S. Maine who were interred in the city cemetery in Key West. Interestingly, the anchor of the Maine is in my home town of Reading, PA, and I always knew that, but I knew very little about how it got there or its significance.

One thing that strikes me about what have become known as America’s Splendid Little Wars (thanks to William Randolph Hearst for that gem) is their connection to the Civil War.

The Secretary of State in the McKinley Administration was John Hay–the same John Hay who was Lincoln’s personal secretary. Nelson Miles was the commanding general of the armies. Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt was the highest ranking Army officer in the field, and was actually recommended for promotion to lieutenant general as a reward for his performance during the Span-Am War. The rank of lieutenant general had been retired after Sheridan’s death, so major general was, once again, the highest rank in the Army. Merritt, at the time of his retirement, was the second ranking officer in the Army as a major general. Unfortunately, lieutenant general was not reinstated in time for him to enjoy its fruits.

The Secretary of State in the McKinley Administration was John Hay–the same John Hay who was Lincoln’s personal secretary. Nelson Miles was the commanding general of the armies. Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt was the highest ranking Army officer in the field, and was actually recommended for promotion to lieutenant general as a reward for his performance during the Span-Am War. The rank of lieutenant general had been retired after Sheridan’s death, so major general was, once again, the highest rank in the Army. Merritt, at the time of his retirement, was the second ranking officer in the Army as a major general. Unfortunately, lieutenant general was not reinstated in time for him to enjoy its fruits.

The Secretary of War in the McKinley Administration was Russell A. Alger, who had commanded the 5th Michigan Cavalry during the Civil War. McKinley, of course, was also a Civil War veteran, as evidenced by the ridiculous monument to him at Antietam.

When the drums of war began to beat again in 1898, Alger was terribly worried that Southerners would not flock to sign up as a result of remaining bitterness over losing the Civil War. So, Alger had an absolutely brilliant idea….he would recruit several former Confederate generals to don the blue uniform of the U. S. Army once again. Three of the four were now politicians, so they were safe.

He chose Thomas L. Rosser, Fitz Lee, the governor of Virginia, Joe Wheeler, Congressman from Alabama, and Matthew C. Butler, US Senator from South Carolina. All were commissioned as major generals of volunteers. Butler, in particular, had impressed Alger during the Civil War, and, specifically, Butler’s brilliant defense at Trevilian Station, where some of Butler’s troops came within a whisper of capturing Alger during what I often describe as “Custer’s First Last Stand.” Lee weighed about 350 pounds at that point and was not fit for duty in the field, and never left the U.S. Butler had had a foot blown off at Brandy Station in June 1863, and also was unfit for duty in the field.

He chose Thomas L. Rosser, Fitz Lee, the governor of Virginia, Joe Wheeler, Congressman from Alabama, and Matthew C. Butler, US Senator from South Carolina. All were commissioned as major generals of volunteers. Butler, in particular, had impressed Alger during the Civil War, and, specifically, Butler’s brilliant defense at Trevilian Station, where some of Butler’s troops came within a whisper of capturing Alger during what I often describe as “Custer’s First Last Stand.” Lee weighed about 350 pounds at that point and was not fit for duty in the field, and never left the U.S. Butler had had a foot blown off at Brandy Station in June 1863, and also was unfit for duty in the field.

However, unlike Lee and Butler, Wheeler, who was still vigorous and active, assumed command of the U. S. cavalry forces in Cuba and was in field command of them at San Juan Hill. It’s been reported that in the heat and excitement of battle, Wheeler slipped and referred to the Spaniards as “Yankees.” Wheeler performed so well in his role in Cuba that he was offered a commission as a brigadier general in the Regular Army, which he accepted. Wheeler was sent to assume command of U. S. forces in the Philippines when a local insurrection broke out. Wheeler did quite well in this role. Theodore J. Wint, about whom I’ve written here, served under Wheeler in the Philippines.

However, unlike Lee and Butler, Wheeler, who was still vigorous and active, assumed command of the U. S. cavalry forces in Cuba and was in field command of them at San Juan Hill. It’s been reported that in the heat and excitement of battle, Wheeler slipped and referred to the Spaniards as “Yankees.” Wheeler performed so well in his role in Cuba that he was offered a commission as a brigadier general in the Regular Army, which he accepted. Wheeler was sent to assume command of U. S. forces in the Philippines when a local insurrection broke out. Wheeler did quite well in this role. Theodore J. Wint, about whom I’ve written here, served under Wheeler in the Philippines.

On June 10, 1898, President McKinley appointed Rosser a brigadier general of United States volunteers during the Spanish-American War. His first task was training young cavalry recruits in a camp near the old Civil War battlefield of Chickamauga in northern Georgia. He was honorably discharged on October 31, 1898, and returned home.

When the Boxer Rebellion broke out in China in 1901, Brig. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, Sr. was sent to take command. He was one of the highest-ranking officers in the Army, and was destined to become the Army chief of staff. Chaffee was badly wounded as a 21-year-old lieutenant at the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield. He was brevetted for obeying a War Department order and not giving his parole when he was captured after being wounded. This began his rise to the highest echelons of the U. S. Army. Again, my guy Wint served under Chaffee, Sr. in China, and, in fact, commanded all of the Allied cavalry forces there, which included the U. S., British, and German troops.

James Harrison Wilson, the famed Union cavalryman of the Civil War, who designed and implemented the first truly mobile strike force with his all-cavalry army of 1865, became a major general of volunteers in the Puerto Rican campaign against the Spanish, and was involved in fighting in the center of the island, near Coamo and Aibonito. Wilson retired in 1901, with the rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army.

James Harrison Wilson, the famed Union cavalryman of the Civil War, who designed and implemented the first truly mobile strike force with his all-cavalry army of 1865, became a major general of volunteers in the Puerto Rican campaign against the Spanish, and was involved in fighting in the center of the island, near Coamo and Aibonito. Wilson retired in 1901, with the rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army.

What’s particularly interesting to me about this is that of these officers, Nelson Miles was the only one who was not a cavalryman. Another interesting point is that three of the four ex-Confederates (Lee, Rosser, and Butler) were former adversaries of Alger’s, and all four of them had fought on the same field at Trevilian Station. Hmmmmm……..

There is a lot of interesting stuff to be gleaned from all of these “Splendid Little Wars,” and I am now working on learning some of it. While our present “splendid little wars” do not involve the standard form of imperialism that drove these wars of the late Nineteenth Century, we’re presently engaged in some similar conflicts around the world. I cannot help but be drawn back to the words of Alphonse Karr after the French Revolution: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” ~ Translation: “The more things change, the more they remain the same.”

Scridb filterA few observations about the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which I’ve done some reading about over the past few years:

1. Napoleon III most assuredly did not inherit his uncle’s military prowess. In fact, he was almost completely incompetent. He reminds me a great deal of the current occupant of the White House: all gung-ho for war, and then incapable of doing the job correctly. Both were utterly incompetent war-time leaders.

2. The Schlieffen Plan worked big time in 1870, just like it did in 1940, and as it nearly did in 1914. You would have thought that the French would have learned something from that, but they certainly didn’t.

3. If the Civil War was the last Napoleonic war, the Franco-Prussian War, just five years later, was definitely the first truly modern war. Talk about an instance where technology made a huge difference….the guns manufactured by Krupp were a quantum leap in the artillery (the French were still using their smoothbore Napoleons), and they made all prior artillery obsolete. Just five years after the end of the Civil War, virtually all soldiers on both sides were armed with breech loading repeating rifles and not the muzzle loaders that were so prominent during the Civil War. The German General Staff also demonstrated, once and for all, that a modern staff system like the ones used today were far preferable to a single commander a la Henry W. Halleck. What’s particularly interesting about this is the quantum leap in technology that occurred in just five years from the end of the Civil War. That is, I think, what I find most striking about it.

4. The seizing of Alsace-Lorraine by the Germans made WWI inevitable. The French were bound and determined to get it back, no matter what. It also was a major bone of contention in the days leading up to the beginning of WWII. Once again, you would think that the French would have learned something over the years, but it’s also pretty obvious to me that they haven’t here, either.

5. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 is an example of what happens when the press fans the flames and events spiral out of control. The same phenomenon brought about the Spanish-American War of 1898, and also played a major role in the outbreak of World War I. This aspect fascinates me.

6. The defeat of the French was a direct trigger to the Paris Commune. This undoubtedly laid the seeds of Communism, and showed that Republicansim was the first stage of the process, i.e., Russia and China. The direct result of the Russian Empire being defeated in World War I was the rise of the Bolsheviks. Hence, it’s clear that the defeat of the French Republic had far-reaching consequences that went far beyond what was obvious at the time that the war was commenced. It seems to me that the present occupant of the White House could have learned a few important lessons from this before invading Iraq.

7. Those who fail to learn the lessons of history are bound to repeat the same mistakes again and again. See item #1 above.

Scridb filterMark Grimsley has an interesting post on his blog today about writing. Like me, Mark has been writing in some form or another for nearly his entire life. Like me, it’s something that he struggles with, constantly trying to improve his skills. In his post, Mark mentions a book titled Professors as Writers, which is intended to help academics improve their writing skills. What makes this pertinent to me is that the book seems to provide a recipe for making the most effective and most productive use of small blocks of time.

Mark’s days are filled with teaching, grading papers, meeting/counseling students and advisees, tending to his bureaucratic/administrative duties at the university, and shoehorning in time to do research. Consequently, he finds himself with only small blocks of time for writing.

My days are not much different. My days are spent meeting with clients, going to court, doing depositions, client development, administrative duties, tending to Ironclad’s needs, and more other distractions than I could hope to describe here. In short, my days are filled, often too filled. I’ve had to learn to do just what Mark’s talking about–being extremely efficient in my use of time. When it’s time to write, I try to set aside two hour blocks for doing so. I try to write three nights a week (it doesn’t matter which three, so long as I get three). Susan knows that when I’m in writing mode, it’s basically total immersion, that I get so focused and intent on what I’m doing that I’m barely conscious of what’s going on around me.

With my short attention span, that’s how it has to be. Otherwise, I get distracted, and if I get distracted, I’m done. It’s really that simple. To her everlasting credit, Susan knows and understands that about me, and she is usually willing to do what it takes to accommodate that, even if it means that I’m not much help with things like laundry or letting the dogs out. The trade-off, of course, is that when I’m not writing, I have to do what I can to help with these things, and I do so whenever possible.

People often ask how I’m able to be as prolific as I am with the incredibly hectic/insane schedule that I keep. It’s because I am able to completely immerse myself in my writing work several nights per week, and if I wasn’t, I wouldn’t come close to finishing anything. My ability to do so is entirely dependent upon my terribly understanding and patient wife, without whom none of this would be possible.

Scridb filterSpam is one of the greatest irritants of my life. Because I am active on-line, I get more spam e-mail than you can shake a stick at. It clogs my mailboxes and bugs me to no end. If I had my way–if I was king of the world–spamming and virus writing would be subject to the death penalty. Justice would be swift, painful, and there would be no right of appeal. Death would be by the most slow, painful torture I can conjure up.

The latest tactic that these scumbag lowlifes have adopted is to spam blogs, too. Tonight alone, I have gotten six attempts to insert spam comments into various posts on this blog. Fortunately, my controls are set so that all first-time commenters have to be approved by me. If it’s obvious spam–tonight’s were for Viagra and porn–they get deleted instantly and have no chance of ever seeing the light of day. Others are a little more crafty. The send a comment that seems marginally on topic–such as “Great information, just what I was looking for”–with the idea being that if it seems on topic, you will approve it, and then they’re in, with carte blanche to spam you any time they want.

Consequently, I check every new comment carefully. If anyone new comments, and your comment never appears, it’s because something about it caused me to be suspicious. Please don’t be offended–I’m just defending my site in the perpetual war against spam. If you think I’ve deleted your comment wrongfully, please e-mail me and I will be happy to reconsider.

The owner of the company where this site is hosted tipped me off to some software that will help with fending these turds off, and I expect it will be installed in the next day or two. I will let you all know when it has been installed. Hopefully, its installation won’t bugger anything up here.

The wars–against spammers and neo-Confederates–never end. And I will never stop fighting them.

Scridb filterWhile doing some updating to my Rush’s Lancers manuscript this evening to incorporate some of the material that I put up last night on Albert P. Morrow, I noticed that Morrow’s service records indicated that while he was a POW the last time, he was charged with a violation of Article 42 of the Articles of War. Now mind you, I may be a lawyer, but I’m not particularly familiar with the Articles of War as they existed in 1863. In fact, my knowledge of them is minimal at best. So, in order to describe this episode accurately in the footnote, I had to find out precisely what he was being charged with doing.

Consequently, I did a Google search to see if I could find the 1863 version of the Articles of War in order to determine precisely the nature of the charges against Morrow. I found a nice AOL member site that includes both the Union and Confederate Articles of War. Both sets of Articles are repeated there verbatim, and it was interesting to compare and contrast them. They are quite similar, with the obvious exception of how they deal with the issue of runaway slaves and contrabands.

Article 42 of the Union version provides: “No officer or soldier shall be out of his quarters, garrison, or camp without leave from his superior officer, upon penalty of being punished, according to the nature of his offense, by the sentence of court-martial.” Thus, when Morrow was arrested, he was charged with being AWOL from the time he was captured on May 13 until he reported back to the regiment. Those charges were dropped immediately upon his showing that his being AWOL was as a result of his being a guest in Libby Prison.

It’s an interesting site that provides useful information.

Dr. Tom Lowry has done some interesting work on Lincoln’s interventions to commute the death sentences of soldiers sentenced to die by courts-martial, on the court-martials of 50 Union surgeons, and on the court-martials of 50 Union lieutenant colonels and colonels. Obviously, the Articles of War–long since supplanted by the Uniform Code of Military Justice–provided the framework for these court-martials, so it’s clear that there is interest in these legal issues. Lowry’s done good work. Check it out if this legal stuff interests you.

Scridb filterTime for another of my periodic tributes to forgotten cavalrymen.

Albert Payson Morrow, born in 1842, was from Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He was named for the town of Payson, Illinois. His father was the headmaster of the Hugh Morrow Select Boarding School in Hatboro, a private school he owned and operated. Ally, as he was known to the family, was a slender, handsome young man, 5’11”, with a fair complexion and flashing blue eyes. He was a scholarly sort who preferred Shakespeare and considered himself to be an expert on the subject. He often helped his father teach the younger boys. As a youth, Albert expected to become a teacher and to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Albert Payson Morrow, born in 1842, was from Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He was named for the town of Payson, Illinois. His father was the headmaster of the Hugh Morrow Select Boarding School in Hatboro, a private school he owned and operated. Ally, as he was known to the family, was a slender, handsome young man, 5’11”, with a fair complexion and flashing blue eyes. He was a scholarly sort who preferred Shakespeare and considered himself to be an expert on the subject. He often helped his father teach the younger boys. As a youth, Albert expected to become a teacher and to follow in his father’s footsteps.

In April 1861, Albert and his brother Leslie enlisted in a 90-day unit, the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry as sergeant, Co. K. He served in Washington, D.C. and saw some combat until Albert fell ill. He mustered out with the regiment on August 1, 1861. A month later, he enlisted in Co. C of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry as sergeant, Co. C (his brother Leslie was appointed an officer in the U. S. Navy at that time). Six weeks later, he was promoted to first sergeant of Co. L, and to sergeant major of Co. F in February 1862. On March 17, he was again promoted, this time Regimental Sergeant Major.

He fought in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, received a vicious saber blow to the head at Bethesda Church on June 13, and was captured. He spent several months in Libby Prison before being exchanged at the end of August. Sick and malnourished, he reported for duty on September 6, fighting with the regiment in the Maryland Campaign. In November, he made first lieutenant of Co. C. He was captured a second time at Chancellorsville and was exchanged almost immediately, just to be captured again by Mosby’s men on May 13. He was again sent to Libby Prison, but was paroled on May 25 and was back with the regiment again on June 8, just in time to participate in the Battle of Brandy Station.

Morrow was wounded again at Greencastle, Pennsylvania while on a raid with Ulric Dahlgren on July 4, 1863. In the process, he had impressed his division commander, Brig. Gen. John Buford, who noted the young man’s fearlessness and valor. When he returned to duty later that month, he joined Buford’s staff. After Buford’s death in December 1863, Morrow returned to his regiment and was promoted to captain of Co. B. He fought in all of the campaigns of the Cavalry Corps in 1864 and was promoted to major in February 1865. On March 20, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and received another severe combat wound at Gravelly Run on March 31, 1865. The bullet was never removed, and caused him suffering for the rest of his life. However, this wound gained him a brevet to colonel for valor. He mustered out with the regiment in August 1865 at age 23, having been captured three times, wounded three times, and was promoted eight times during the war.

Morrow was wounded again at Greencastle, Pennsylvania while on a raid with Ulric Dahlgren on July 4, 1863. In the process, he had impressed his division commander, Brig. Gen. John Buford, who noted the young man’s fearlessness and valor. When he returned to duty later that month, he joined Buford’s staff. After Buford’s death in December 1863, Morrow returned to his regiment and was promoted to captain of Co. B. He fought in all of the campaigns of the Cavalry Corps in 1864 and was promoted to major in February 1865. On March 20, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and received another severe combat wound at Gravelly Run on March 31, 1865. The bullet was never removed, and caused him suffering for the rest of his life. However, this wound gained him a brevet to colonel for valor. He mustered out with the regiment in August 1865 at age 23, having been captured three times, wounded three times, and was promoted eight times during the war.

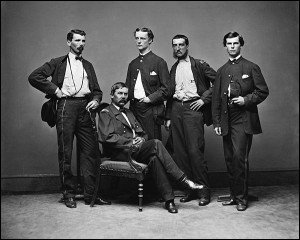

The very handsome young man was quite popular with the ladies. His friend Myles W. Keogh wrote of him that he was “the devil among the ladies, as we say in the Emerald Isle.” He served with Keogh on Buford’s staff. In the photo above, Morrow is on the far right, and Keogh on the far left, both standing behind Buford.

Morrow soon realized that he was destined to be a soldier and not a school teacher. He missed the routine of Army life and the thrill of combat. On July 28, 1866, Morrow was commissioned as a captain in the newly-formed 7th U. S. Cavalry, quite an accomplishment for a young man with no formal military training. Another company commander in the 7th U. S. Cavalry was Myles W. Keogh, with whom Morrow had served on the staff of General John Buford. Morrow’s commissioning into the 7th U. S. reunited these two old friends and comrades in arms. He served on frontier duty with his regiment at Fort Hays, Kansas until he was transferred to the 9th U. S. Cavalry and promoted to major in March 1867. The 9th U. S. Cavalry consisted of African-American soldiers, and was one of the famous “Buffalo Soldier” regiments that served in the West with great distinction during the latter stages of the Nineteenth Century.

Morrow participated in various expeditions against hostile Indians, including the 1876 Sioux Campaign and an 1878 campaign against the Ute Indians. In the fall of 1880, he was sent to France to witness maneuvers of the French army, and did not return to the United States until January 1881, when he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed aide-de-camp to the commanding general-of-the-army, William T. Sherman. He served in that capacity until June 1, 1883, when he was relieved of that duty and returned to his regiment in Arizona. He was promoted to colonel of the 3rd U. S. Cavalry on February 18, 1891, and served in Texas until he retired from active duty in August 1892. During a long and successful career as an Indian fighter, Morrow received many commendations. After his retirement, Morrow was active in the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), Colorado Commandery, and died on January 20, 1911.

Here’s to another long-forgotten Union soldier, a man of great courage and ability who served his country with great distinction for more than thirty years.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like