Category:

Union Cavalry

Pictures from my trip…

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

These are sixteen photos from my trip this past weekend. This first batch are from the battlefield at Five Forks.

This photo was taken at the right end of the Union line at Five Forks, where the Union cavalry hit the Confederate line.

This photo shows the Confederate trenches extending back into the woods at the angle of the Confederate line, where part of it bent back to refuse the flank. It’s not easy to see them clearly, but they’re there. They’re on the left side of the photo, and snake back into the woods.

This is the monument to the Battle of Five Forks, which is located at the intersection where the five roads come together.

This is the position where Col. Willie Pegram’s guns were, and where Pegram received his mortal wound. Behind the gun is the old visitor center at Five Forks. It’s an old gas station and is obviously not a historic structure. On March 26, ground will be broken to build a new visitor center for Five Forks, and once it’s done, this thing will be torn down.

This is far end of the Confederate line at Five Forks, where Fitz Lee’s cavalry was routed. Look at those open fields, perfect for mounted operations.

I also stopped at the Sutherland’s Station battlefield on my way back toward Petersburg. I’d never seen it before. Sutherland’s Station was fought on April 2, 1865 and marks the final cutting of the Southside Railroad by the Union army. These are two historical interpretive markers there.

This is a monument to the Confederate forces who fought at Sutherland’s Station.

This is the small marker on the spot where Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill received his mortal wound. It’s near Pamplin Park, behind a subdivision. I don’t think many people visit the spot.

This is from Thursday afternoon, although we visited this spot on Saturday. Bobby Krick took me here. These earthworks represent a small surviving section of the outer ring of defenses of Richmond. These works were briefly occupied by Judson Kilpatrick on March 1, 1864 and by Phil Sheridan on May 12, 1864. Both ultimately decided that they could not carry the intermediate line of works.

This lovely home is called Rose Hill. It’s at Stevensburg, VA, and served as Judson Kilpatrick’s headquarters during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. We had a tour of the home. The fellow in the brown jacket is my old friend Horace Mewborn, who is pretty much THE authority on Mosby’s Rangers.

Our tour leader, Dr. Bruce Venter, THE authority on the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid, holding court on Friday.

This is a nifty little monument to a trooper of the 4th Virginia Cavalry named Pvt. James Pleasants, who captured 13 men and killed one after being roused by Dahlgren’s raiders as they passed through Goochland County on March 1, 1864.

This is the James River in Goochland County. Dahlgren tried to cross here (it’s usually fordable), but when Dahlgren’s column came through, the river was at freshet and could not be forded. Dahlgren tried again about three miles further downriver and failed a second time.

This was Benjamin Greene’s farm in the Westhampton section of Richmond. This spot marks the focus of the battle between Dahlgren’s men and the defense forces of Richmond that occurred late in the afternoon of March 1, 1864. We were there at about the same time as the battle, so we were able to get a real sense of what it was like as the fighting raged. The house then served as a hospital. We were permitted into this gorgeous old house, and it’s quite a place to see.

This is Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. Kilpatrick burned it during the raid, and Custer did so again during the May Richmond Raid. It was a popular spot.

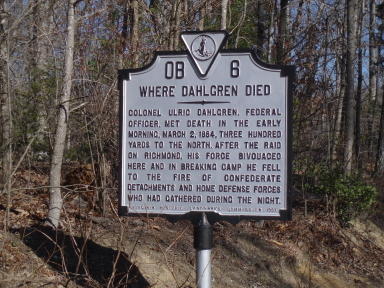

This is the Virginia historical marker at the site where Ulric Dahlgren was ambushed and killed. It’s pretty much self-explanatory, although it’s not entirely accurate. Dahlgren was killed between 10 and 11 at night on March 2, not in the early morning hours, and he was killed pretty much at the site of the marker, and not a couple of hundred yards away, as the marker indicates. Our visit to the ambush site pretty much marked our final stop of the tour.

I took a few more photos, but these ought to give you a taste of the trip. It was a very good but exhausting time. We covered nearly 375 miles in the bus, and saw an awful lot. We spent nearly two full days touring and seeing the sites. I’m glad that I went, as I came away from the tour wit a lot of different insights and perspectives on things that have subsequently made their way into the manuscript.

Scridb filterAnother Long Day….

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

We were up and on the bus at 8:00 again this morning. We headed up to Beaver Dam Station, a stop on the Virginia Central Railroad not far from the North Anna battlefield of May 1864. We heard about Kilpatrick’s demolition of the depot there, and then headed down into Richmond to address Kilpatrick’s attempt to push through the defenses of the Confederate capital. A small piece of the outer ring of defenses still exists at Brook Hill, which happens to be the spot where both Kilpatrick in March 1864 and Sheridan in May 1864 tried to push through. Bruce interpreted there, and then we headed in to where the intermediate line of defenses stood.

Kilpatrick, alone and unsupported, and with Bradley T. Johnson’s 1st Maryland Cavalry operating in his rear, for once, made the prudent decision and broke off instead of sending his mounted cavalrymen charging into the static defenses of Richmond. He then headed for Meadow Bridges, crossed the Chickahominy swamp there, and marched toward Atlee’s Station. There, a portion of Wade Hampton’s division, with Hampton in personal command, routed the 7th Michigan Cavalry and persuaded Kilpatrick to get out of Dodge. He fled toward Kent City Courthouse, where he met a relief column sent from Williamsburg by Ben Butler. Our last Kilpatrick stop was at Tunstall’s Station on the old James River Railroad, where Kilpatrick burned the station and was joined by the portion of Dahlgren’s command that broke through Johnson’s Confederates to rejoin the main body.

From there, it was on to the area of Hanovertown Ferry, where Dahlgren’s remnant of about 100 men crossed the Pamunkey, and then on into King and Queen County. We crossed the Mattaponi at Ayletts, just as Dahlgren did, and then proceeded on to the ambush site. After interpreting the ambush, Bruce and I laid out our respective theories as to who knew and approved what regarding the plan and the legitimacy of the Dahlgren Papers. Bruce believes Dahlgren cooked it all up on his own, while I believe it was cooked up by Kilpatrick and Stanton and that Dahlgren likely participated in the process.

That was the end of the tour, and we then headed the 30 miles back to Richmond. Along the way, Bruce gave some analysis of the raid and its results and consequences, and I spent most of the ride back hashing out some new thoughts/insights that I developed over the last two days as a consequence of both seeing the sites as well as having the benefit of having Bruce’s analysis and commentary. After saying our goodbyes, I headed straight back up to my hotel room and incorporated all of the new stuff into the manuscript. While I thought that the manuscript was good previously, I think that it’s even better now. I feel really good about it, and think it’s going to make for a really good conclusion chapter to my biography of Ulric Dahlgren.

I’m now sitting in my hotel room, hanging out. Pretty much everyone who attended the conference dispersed immediately after the conclusion, and I have a very early flight tomorrow. My flight home is at 7:30, and it’s nearly 20 miles to the airport. That means it’s up at 5:00 again tomorrow. I CANNOT wait until Skybus starts its second flight per day to Richmond, which will leave Columbus at 5:00 PM. No more of these ridiculously early mornings.

Tomorrow night, when I get home, I will post some photos from the weekend. For now, it’s time to just rest and try to get ready for what’s going to be another long and stressful week.

Scridb filterEleven Hours On the Road

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

We spent eleven hours on the road today. We left our hotel at 8:00 this morning and made our way up to Culpeper, which is about 80 miles from Richmond. We visited Rose Hill, where Judson Kilpatrick had his headquarters during the winter of 1863-1864, had a tour of the house, and then set out to follow the route of the raid.

Our next stop was Eley’s Ford, where the entire Federal column crossed the Rapidan River, and then on through Chancellorsville, through Spotsylvania, and on into the countryside. We covered part of Kilpatrick’s route and part of Dahlgren’s route. We made our way out into Goochland County, including stopping by Sabot Hill, the plantation of Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon. From there, we made our way down to the banks of the James River to see the spot where Dahlgren’s column failed to cross due to the flooded condition of the river. From there, we went on to Tuckahoe Plantation, and on into Richmond, where we covered Dahlgren’s fight at the gates of Richmond in greater detail than I have ever heard.

That was the end of the day’s travels. According to our bus driver, we covered 213 miles today. That’s a lot of ground to cover. We saw lots of things that I have never seen previously, some of which pertain to other actions (much of Kilpatrick’s route follows the route taken by Sheridan’s May 1864 Richmond Raid), and I now have a much better understanding of the action where Dahlgren received his repulse. Previously, I’d had to try to figure it out myself, and while I got most of it, I now have a solid understanding of the action, which is why I’m here.

I just got back from some delightful dinner conversation with fellow blogger Donald Thompson of Touch the Elbow, who’s also along for the ride. I always particularly enjoy meeting other bloggers, and I’m the one who’s responsible for Donald being along this weekend, so I wanted to make sure that I got to spend some time with him. We had a good talk about lots of things, and then it was time to call it a night. I’m going to tweak my Dahlgren manuscript a little bit to reflect some insights I got today while they’re still fresh in my mind, and then I think it will be time to call it a night.

We probably have another 200 miles and another 10 hours of travel and touring tomorrow……

Scridb filterGreetings from Richmond

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Greetings from Richmond. It’s almost 10:30 at night as I write this. I’ve been up since 4 AM, so I’m about half delirious and ready to go to sleep. I’m here for old friend Dr. Bruce Venter’s Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid tour. My flight left Columbus at 6:00 AM, so it’s been a long day. Today, I went to Five Forks, made a quick stop at Pamplin Park, visited the new museum at Tredegar–I meant to tour the museum, but some loyal readers of these rantings shanghaied me, and we ended up talking shop for an hour instead. Then, I picked up Bobby Krick at the Chimborazo Hospital site, which is where Bobby’s office is, and we went and visited a bunch of nifty 1864 cavalry battle sites. That took the entire afternoon, and then the program began this evening. I’ve managed to burn up 3/4 of a tank of gas in the rented PT Cruiser (I signed up for a subcompact and they gave me a PT Cruiser for the same rate) today driving around. Needless to say, I’m beat.

More tomorrow when I’m a little more coherent.

Scridb filterCavalry Tour de Force

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

C. E. Peck of the 15th New York Cavalry, on the role of horse soldiers:

“Cavalry is the whirlwind of war. Batteries thunder and crush – – infantry forms the conflicts, surge and shock, but it is the charge of horse – – a wild erratic horse – – that seems the very tempest of the strife. Half man, half brute, it knows no fear – – an awful swell of carnage and commotion – – a terrible, relentless deluge of trampling hoofs and hewing steel. But as magnificent as are the rush and clash of the cavalry in the crucial moment of a victory, not less of danger, not less of duty, not less of service are in its constant, tireless movements, in the skirmish and the foray, as the blind force of strategy, and guardian of an army.”

Good stuff.

Scridb filterCol. Sir Percy Wyndham

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

My profiles of forgotten cavalrymen usually focus on men whose outstanding contributions to their cause made a difference in the outcome of the war. Every once in a while, though, it’s fun to pay tribute to a scoundrel. Today, we pay tribute to a true rascal.

Col. Sir Percy Wyndham was born on the ship Arab in the English Channel on February 5, 1833, while his parents were en route to Calcutta, India. Capt. Charles Wyndham, his father, served in the British Fifth Light Cavalry. With that pedigree, the boy was destined to be a horse soldier. However, fifteen-year old Percy Wyndham entered the French navy instead, serving as a midshipman during the French Revolution of 1848. He then joined the Austrian army as a sub lieutenant and left eight years later as a first lieutenant in the Austrian Lancers. He resigned his commission on May 1, 1860 to join the Italian army of liberation being formed by the famed guerrilla leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, and received a battlefield promotion to major in the great battle of Milazzo, Sicily on July 20, 1860, where Garibaldi’s army defeated the Neapolitans, consolidating the guerrilla’s hold on the island. A grateful King Victor Emmanuel knighted the dashing cavalryman. With the conquest of Italy complete, the soldier of fortune went hunting for another opportunity, and found one in the United States in 1861.

Col. Sir Percy Wyndham was born on the ship Arab in the English Channel on February 5, 1833, while his parents were en route to Calcutta, India. Capt. Charles Wyndham, his father, served in the British Fifth Light Cavalry. With that pedigree, the boy was destined to be a horse soldier. However, fifteen-year old Percy Wyndham entered the French navy instead, serving as a midshipman during the French Revolution of 1848. He then joined the Austrian army as a sub lieutenant and left eight years later as a first lieutenant in the Austrian Lancers. He resigned his commission on May 1, 1860 to join the Italian army of liberation being formed by the famed guerrilla leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, and received a battlefield promotion to major in the great battle of Milazzo, Sicily on July 20, 1860, where Garibaldi’s army defeated the Neapolitans, consolidating the guerrilla’s hold on the island. A grateful King Victor Emmanuel knighted the dashing cavalryman. With the conquest of Italy complete, the soldier of fortune went hunting for another opportunity, and found one in the United States in 1861.

Sir Percy offered his services to the Union with the coming of war in the spring of 1861. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who quickly rose to command all of the Union armies, was familiar with Wyndham’s reputation as a fighter, and recommended him to be the colonel of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry. Although the governor of New Jersey issued the commission in February 1862, the men of the 1st New Jersey did not welcome the Englishman with open arms. A local newspaper wondered, “Have we no material in New Jersey out of which to manufacture competent colonels without resorting to foreigners to fill up the list?” However, when he instituted discipline, improved their food, got regular pay for his men, and moved their camp out of a swamp, the troopers changed their minds about their new commander.

Sir Percy made quite an impression. A Federal horseman recalled, “This officer was an Englishman, an alleged lord. But lord or son of a lord, his capacity as a cavalry officer was not great. He had been entrusted with one or two independent commands and was regarded as a dashing officer…He seemed bent on killing as many horses as possible, not to mention the men. The fact was the newspapers were in the habit of reporting that Colonel or General so-and-so had made a forced march of so many hours, and it is probable that ‘Sir Percy’ was in search of some more of that kind of cheap renown.”

One Confederate trooper noticed that Sir Percy, who wore a spectacular mustache nearly two feet wide, was “a stalwart man…who strode along with the nonchalant air of one who had wooed Dame Fortune too long to be cast down by her frowns.” A Federal officer called Wyndham “a big bag of wind.” Another Northerner, remembering his first encounter with Wyndham, compared him to a bouquet of flowers, noting, “You poor little lillies, you! You haven’t the first the glorious magnificence of his beauty. He’s only been in Camp for two hours, and he now appears in his third suit of clothes!”

During Jackson’s Valley Campaign of 1862, Wyndham impetuously led his regiment in a charge into Turner Ashby’s cavalry, and Wyndham was captured on June 6, 1862. He was paroled on August 17. When he returned to duty, he was assigned to command a brigade in Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard’s cavalry division.

Wyndham’s brigade included his own 1st New Jersey Cavalry, the 12th Illinois Cavalry, the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, and the 1st Maryland Cavalry. In early 1863, while his brigade was headquartered at Fairfax Court House, Wyndham was given the task of running down the guerrillas of John S. Mosby. Sir Percy did not approve of Mosby’s unorthodox tactics, and called him a horse-thief. Sir Percy threatened to burn down towns if their inhabitants did not tell what they knew about the whereabouts of Mosby and his men, a policy that did not endear the Englishman to any of the locals.

Offended by being called a horse thief, Mosby decided a personal response was in order. When a deserter from the 5th New York Cavalry disclosed the location of Wyndham’s headquarters, Mosby raided the place on the night of March 9, 1863. Sir Percy had left for Washington the day before, and missed the humiliation of being captured in his bed, as two of his aides and Brig. Gen. Edwin M. Stoughton were. Mosby had to content himself with capturing some of Sir Percy’s uniforms.

Sir Percy’s brigade performed well during the Stoneman Raid of 1863, reaching the outer defenses of Richmond before turning away. His finest moment was at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. He personally led his brigade’s charge up Fleetwood Hill, engaging in hand-to-hand combat until they were driven back by the weight of enemy numbers. Although his troopers were badly outnumbered, he personally rallied a rear guard and forced the pursuing Confederates back with two hell for leather saber charges. Sir Percy received a severe gunshot wound to the leg, but stayed in the saddle until loss of blood finally forced him to retire. “It affords me no small degree of pleasure to be able to say that all of my command that followed me on the field behaved nobly,” he proudly wrote of his brigade’s performance, “standing unmoved under the enemy’s artillery fire and, when ordered to charge, dashing forward with a spirit and determination that swept all before them!”

Sent to Washington to recuperate, he assumed command of the cavalry units assigned to the capital’s defenses. During Stuart’s advance on Washington on his way into Pennsylvania, Sir Percy scraped together a force of 3,000 fully equipped horsemen, but they did not end up facing the enemy.

When he returned from a leave of absence in October 1863, he was charged with “absence without leave”, his leave having expired on September 5. He was relieved from all duty “and ordered to proceed to Washington, but not in arrest.” On October 3, 1863, Sec. of War Edwin M. Stanton issued an unusual order: “Information received at this Department indicates that Colonel Percy Wyndham should not be permitted to have a command or come within the lines of [the Army of the Potomac].” Historian Roger Hunt speculates that this order stemmed from rumors that Wyndham was involved in a plot to kidnap Lincoln and his cabinet. Sir Percy repeatedly applied for reinstatement, but was rebuffed.

Undaunted, he returned to the army in April 1864 in a volunteer capacity, “rendering all the service in my power for the advancement and success of the Union cause.” When Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, learned that Wyndham was with the army again without authority, on June 26, 1864, he ordered that Wyndham “be sent by the Provost Marshal General to Washington, in charge of an officer, and reported to the Adjutant General.” On July 2, Stanton ordered, “Colonel Wyndham will be mustered out of service,” effective July 5, 1864.

Now a civilian, Sir Percy settled in New York, where he established a military school. In 1866 he returned to Italy to serve on Garibaldi’s staff. When the Italian war ended, he and a friend who was a chemist went to New York to start a petroleum refining business. Unfortunately, an explosion destroyed the main refinery and ruined the business. Ever restless, he soon left New York for India. He settled in Calcutta and established a comic newspaper, The Indian Charivari, modeled on London’s Punch. He founded an Italian opera company and married a wealthy widow. A failed business logging teak in Mandalay, Burma, ate up all of the wealth earned from his Indian businesses.

Returning to his mercenary roots, he briefly served as the commander in chief of the Burmese army, but was left penniless by the failure of his many businesses. He was fascinated by huge balloons, and undertook the construction of one. In January 1879, the huge balloon (70 feet tall and 100 feet in diameter) exploded with him aboard at an altitude of 300 feet. The flamboyant English soldier of fortune was dead at the young age of 46. His body was not found.

Here’s to Col. Sir Percy Wyndham, English soldier of fortune, scoundrel, and wearer of some of the most spectacular facial hair ever seen on this continent.

Scridb filterThe Forrest Issue, Redux

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

As you will recall, last week, I posted here about a thread that I had started on the Armchair General forum boards about the differences between Union cavalry in the Eastern vs. Western Theaters of the war.

When I began that thread, I was afraid the someone would hijack it and try to turn it into a “Nathan Bedford Forrest was God” discussion, and I worked very hard to try to prevent that. After years of study, I remain absolutely convinced that Forrest was nothing more than a nuisance, John S. Mosby on a larger scale (No, Val, this will not become a Mosby discussion, so please don’t go there). My only point was that it’s easy to run up a gaudy won-lost record when you only ever face the junior varsity, and with very few exceptions, that’s what Forrest faced.

One of the Forrest worshippers kept trying to shanghai my thread, and went on and on and on. I finally suggested that we simply agree to disagree on the subject and let it go, but he insisted on taking another shot at it, saying that I couldn’t call Forrest a nuisance until I definitively proved to him that I was right. I hope I just put an end to it. I put up a post saying that it was not my responsibility to prove my opinion, and that my opinion was just that: my opinion. In the hope of preventing an all-out flame war, I said that I would not respond to any further posts on the subject.

I just don’t get it. What is it about Forrest that inspires such emotional and hate-filled responses? Even things that have almost nothing to do with Forrest instigate the inevitable and very predictable response. I have to say that I find it terribly distasteful, and that I think that the best course of action from now on is to simply avoid the topic altogether. Which is sad, considering that I’m a cavalry historian and that that’s the focus of this blog.

Scridb filterMore on Eastern Cavalry vs. Western Cavalry

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Dave Powell left an incredibly insightful comment on last night’s post adding to what I wrote and amplifying on it as well. It was so good, in fact, that I decided to give Dave the bully pulpit here. Here’s Dave’s comment:

Eric,

Thanks for this supremely (to me) interesting post.

A couple of things:

1) I am not sure that Rosecrans really disliked David S. Stanley all that much, despite his faults. However, starting in early september, Stanley was getting ill, which definitely hindered his capacity, so much so that on September 16th Stanley relinquished command and was hauled back to Stevenson by wagon. He would be some time recovering.

The ranking commander under Stanley was a politician that scared both Rosecrans and Stanley – Robert B. Mitchell. (Not exactly a household name in ACW lore.) After Chickamauga, Mitchell was quietly sidelined, being ordered back to DC for court-martial duty, and then later given a series of frontier commands, chiefly Nebraska. He was an Ohio politician, not a soldier, and it showed.

I think that Stanley’s illness, as much as anything, lay behind Rosecrans request for Buford. I wish he had lived to go, too – that would have been the subsequent year extremely interesting.

However, there were a number of highly competent Union Cav guys – mostly brigade-level – who did do very well. Minty, Wilder, and George Crook come to mind. Crook orchestrated the pursuit of Wheeler duing his October 1863 raid, in which Wheeler lost roughly half his command.

This example and Wade’s point touch on the larger theme that I see about Cavalry in the West. While the Rebel performance there was at times flashy, and “stunt-laden” in the manner that caught many postwar fabulist’s attention, the CSA routinely failed at the critical cav duties that made up the bulk of Cav’s role, as boring as it was.

Stuart might have had his stunts, riding around the AOP and the like, but his men also performed well in the scouting and screening role. That was a marked difference between east and west.

This goes hand in hand with Ethan Rafuse’s column over on Civil Warriors as well, and accepting the idea that the CSA cavalry was equal on both fronts, but Union cav was weak in the west.

In fact, I think the CSA cavalry was a massive failure in the west. Even in raiding, with a few exceptions, they failed to achieve much of significance.

First, never overlook the fact that the CSA invested huge numbers in CSA cavalry between the mountains and the Mississippi. It is the only branch were the CSA has the advantage of numbers – sometimes 2/1, usually a 3/2 ratio – for much of the war. Despite this, it rarely effects Union operations, and the Rebel horse never manages to win the scout/screening fight.

For example, in the Spring of 1863, the CSA Cavalry in East Tennessee, with Bragg, and in Pemberton’s theater amount to nearly 30,000 men – larger than Bragg’s army, BTW. This huge force amounts to more than two infantry corps of strength. (I doubt CSA Cav in VA ever amounted to half that, despite the larger overall field forces Lee commanded.) Union Cav in the west amounted to about half – roughly 17,000 men, not counting the garrison forces in KY that were simply not available for field duty.

A note about those garrisons, because they create a different dynamic than in the East. Federals in the West controlled large areas of disputed territory, far more than in the East, and so each department – Grant in West Tennessee, Rosecrans in Middle Tennessee, and Burnsides in SE KY and East Tennessee – had to leave about 40 % of their troops in permanent garrisons to secure the occupied territories. This is why Grant might muster 90,000 men in his department in March, but can only free up 50,000 to take the field against Pemberton. While the Eastern Feds had garrison issues, (MD and the B&O RR) they tended to be much smaller as a percentage of forces, and often were close enough to the war to have a role to play, during Gettysburg for example.

Despite this disparity in numbers, however, the Rebels were constantly fooled by Union offensives. Rosecrans outmanuvered and Surprised Bragg three times; during the approach to Murfreesboro, famously at Tullahoma, and again in crossing the Tenn. In each case Wheeler failed miserably, at Tullahoma, Forrest contributed significantly to the confusion.

Or consider Grant’s inland operations behind Vicksburg. Both Pemberton and Johnston were paralyzed with indecision, and had terrible intel. Grant had far superior intel despite his lack of cav, because he was able to use the local slave network and he operated in all but a Rebel Cav vacuum.

Burnsides in East Tenn had similar success. Buckner was at first deceived as to Burnsides’ entry points, and later, the cav sent to help Longstreet never managed to dominate against the limited Federal mounted force there.

We can go back to Perryville and see the same pattern, where Bragg completely misreads the two Federal column, thinks Sill’s diversion is the main body, and attacks Buell’s whole army with 15,000 men. Now we can certainly blame Bragg, but we must also blame Wheeler’s horrible intel during the campaign, as well.

Neither Grant nor Sherman needed developed an emphasis on good cav because they never really needed to – they had all the operational freedom and intel they needed without it. this remarkable fact says a lot about the overall incompetence of the CSA cavalry in the west.

yes, there were some spectacular raids. Holly Springs is the most famous. But even Forrest’s great triumph – Brice’s Crossroads – is a strategic defeat. Forrest needs to be operating against Sherman’s supply lines, where he might have some real effect, not aimlessly chasing Sturgis in Northern Mississippi. The mere fact that he is fighting Sturgis and not Sherman is a failure of Confederate strategic thought.

Of course, the indiscipline of the CSA cav in the west played a major role in this ineffectiveness. Wheeler simply could not control his men, who often came and went as they pleased. Thus, while the CSA did have 30,000 armed and uniformed men roaming the western theater in the spring of 63, for example, maybe only 20,000 of them were responding to army discipline at any one time. Two quick examples can demonstrate the scope of this problem:

In August 63, Rebel cav dispersed to refit. Wharton’s men went to Rome, GA, where they proceeed to earn a remarkable reputation as thieves. When they departed for the front they left behind many men who infested the region for the next 6-8 months as bushwackers and bandits. Similarly, when Dibrell’s Brigade moved to Sparta (home turf) that same month, at least half of his 1200 men stayed behind when Dibrell was recalled to open the Chattanooga campaign.

Much more telling, however, are Wheeler’s numbers during the march to the Sea. Wheeler reports roughly 9,000 men on hand at the start of the march, and nearly 8,000 pfd in January, 65, after the march. During the campaign, however, he claims never to have more than 2,500 men with him. Where are the others? Basically, off pillaging. Many of Wheeler’s men are as bad as any of Sherman’s bummers. Wheeler is simply unable to control them, and they are not really interested in fighting.

This topic is large enough to demand far more attention than I can provide here, but hopefully you get the idea.

I feel that one big reason for the CSA defeat is the mismanagement of the Rebel Cav in the west – the one resource, ironically, that the Confederates had (at least) numerical superiority in for almost two years – mid 62 to mid 64.

The glamour that Forrest and Morgan tend to bring to CSA western cav ops is so strong that the strategic realities get obscured by the mythology, but once you start peeling back the layers, it is hard not to realize that tactically, the Federals dominated the scout-screen mission in campaign after campaign.

Dave Powell

Dave is an authority on the Western Theater and has studied cavalry operations in the Chickamauga Campaign in particular. Thanks for the excellent contribution, Dave.

Scridb filterEastern Theater vs. Western Theater Cavalry

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

Last week, I asked this question on the Armchair General forum boards: I’ve often said that part of the reason why I don’t have a great deal of respect for Nathan Bedford Forrest is because, with the distinct exception of James H. Wilson at Selma, he always faced the second team.

Then, there was Wheeler, who enjoyed a modicum of success in spite of not being particularly talented. Wheeler faced pretty much every Union cavalry commander in the West, including the Eastern Theater retreads (he put a damned good whipping on Kilpatrick at Aiken, SC in February 1865).

I have some thoughts on the subject, but I would be interested in hearing why people think that, until Wilson’s independent command was formed during the fall and winter of 1864-1865, the Union cavalry in the West got short shrift and not the best of the commanders or the weaponry that were commonly distributed to the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps.

Because I was interested to see what folks might come up with in response, I waited almost a week to propose an answer to my own question. Here’s what I wrote, which is, I think, a fair summary:

I asked this particular question for a reason. This is an issue that I am often asked about, and it’s also a question that I have spent a lot of time pondering over the years. There is no right or wrong answer, only theories and gut reactions. This is what I’ve come up with over the years. These thoughts are presented in no particular order.

There are a lot of converging reasons for why this is the case. To mix my metaphors for just a moment, it’s like a perfect storm of synergistic reasons all coming together to lead to a situation where there was in fact a wide disparity in the quality of the Western vs. Eastern Union cavalry.

First, and foremost, was the issue of geography. The simple truth is that the Federal capital was in the east, and not the west. Defending Washington was the number one priority of the Army of the Potomac at all times, and that never changed. The Eastern Theater of the war was small, with the opposing capitals a mere 100 miles apart. That meant that there was a small field of operations. The West, on the other hand, was a massive landmass, and few of the major Northern cities were ever seriously threatened by the Confederates, with the limited exception of Morgan’s Indiana and Ohio raid of 1863. Thus, the Federal cavalry in the West tended to be widely dispersed rather than concentrated in a small theater of operations.

In addition, there was no Western theater equivalent to J.E.B. Stuart. Say what you will about Stuart, but if Stuart was not THE finest horse cavalryman ever born on this continent, he has to be in the top two or three. In the earliest days of the war, Stuart and his cavalry had a significant impact. If you need evidence of that, look at the charge of Stuart and 1st Virginia Cavalry at the climax of 1st Bull Run, when his charge into Griffin’s battery and the Fire Zouaves started the Union rout. Then came the Ride Around McClellan, which created so much consternation in the Union ranks that Stuart’s father-in-law, the venerable Philip St. George Cooke, was relieved of command and shunted off to do recruiting duty in Minnesota, the 1862 equivalent of being sent to man a weather station in Alaska.

By comparison, the Confederate cavalry in the West in the early days had Earl Van Dorn, who was much more interested in bedding married women than anything else, and John Hunt Morgan, who was a fearsome raider, but a tactical zero. Later, Joseph Wheeler emerged from the pack. It’s very important to keep in mind that Wheeler emerged not because of competence, but rather because he and Braxton Bragg had a good working relationship, and because Bragg liked Wheeler a great deal. Wheeler, in turn, was loyal to Bragg. Bragg evidently felt that loyalty was a more important measure than competence, and he promoted Wheeler far beyond his level of competence. Forrest (whom I will briefly address later in this discussion) did not really emerge until much later and was really a non-factor in the early days of the war.

The upshot is that there simply was no sense of urgency for the Union cavalry in the West, while there was a great sense of urgency in the East due to the superiority of Jeb Stuart and his cavalry.

The next factor is that there were only so many good battlefield commanders to go around. I believe that the combination of the Stuart factor and the proximity to Washington meant that the bulk of the batter officers would be dedicated to serve in the east and not the west. Once some of the less competent battlefield commanders were weeded out, the competent ones emerged. Officers like John Buford, David M. Gregg, William W. Averell, Wesley Merritt, Thomas C. Devin, and others came up through the ranks to achieve higher levels of command. This process took time. John Buford, generally acknowledged as the best cavalryman in the Federal service, did not achieve brigade command until June 1862. Note how many of these officers rose in the East. It seems like the majority of the better officers were assigned to the East and not the West.

In the West, officers of questionable competence, such as David Stanley, rose to high levels of command. Stanley, a notorious alcoholic, commanded the Army of the Cumberland’s Cavalry Corps for a significant portion of the war. However, Stanley’s performance was so bad during the Chickamauga Campaign that William S. Rosecrans asked to have John Buford sent west to assume command of the Army of the Cumberland’s Cavalry Corps. Buford agreed, provided that he could take the Regulars assigned to the Army of the Potomac with him. However, the Army of the Potomac was in the middle of the Bristoe Station Campaign when all of this happened, and the high command was loath to call them back from the field in mid-campaign. By the time the campaign ended, Buford was already suffering from the typhoid fever that took his life on December 16, 1863. Imagine, though, if you will, the great cavalry battle royale that inevitably would have happened between Wheeler and Buford. My money would have been on Buford for sure.

Then there were the likes of Sam Sturgis. Again, with all due respect to N. B. Forrest (my thoughts on him are well-known and need not be repeated here), it’s not difficult to roll up a sterling won-loss record when you’re up against the likes of Sturgis and not against the best officers that the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps had to offer. I view Forrest and his command as not much more than Mosby’s guerrillas on a larger scale–a major nuisance and not a whole lot more.

The next factor is the size of the theater. It was much easier to concentrate cavalry forces in the Virginia theater than in the West. The simple fact is that the Western Theater covered vast areas of ground, stretching cavalry resources to their limits, while the Virginia theater was much more compact and more conducive to concentrating forces.

The next factor was technology. Because of the nature of the war in the East, the Eastern Theater cavalry were more likely to get the latest technology first, since the safety of nothing less than the Federal capital was at stake. By the beginning of May 1864, nearly the entire Army of the Potomac Cavalry Corps had been armed with Spencer repeating carbines. Many fewer Western Theater units had repeaters, and some never did get them. However, Wilder’s Lightning Brigade, a brigade of mounted infantry armed with Spencer repeating rifles, demonstrated without any question just how effective a unit armed with repeating weapons could be. Wilder’s command was rather literally all over the battlefield at Chickamauga, and no Federal unit played a more important role as a consequence of the combination of maneuverability and firepower. From and ordinance standpoint, the Western Theater seems to have gotten the short shrift.

Leadership at the highest levels also factors in. John Pope certainly can be criticized for many things, including his terrible handling of the Battle of 2nd Bull Run, and rightfully so. However, one area where he cannot be criticized is in his recognition of the value and power of cavalry. Pope was the first to brigade volunteer cavalry regiments, and they did good service under him during the Island No. 10 Campaign and also in the 2nd Bull Run Campaign. It is not a huge stretch to suggest that of all of the Union army commanders during the Civil War, none had a better understanding of the proper and most effective use of horse soldiers than did Pope.

While Grant clearly understood the importance of a strategic cavalry raid (see Grierson’s Raid if you need an example of that), he was not good at using his cavalry as part of his army. This weakness carried itself through the 1864 Overland Campaign, when he sent the entire Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac off on a raid on Richmond intended to draw Stuart and his horsemen out to fight. By leaving the army to grope its way along blindly, Grant nearly fell into a trap set for him at Ox Ford on the North Anna River. Grant never learned these lessons in the west.

Sherman also was not especially good at using is cavalry. For a detailed analysis, see David Evans’ superb Sherman’s Horsemen: Union Cavalry Operations in the Atlanta Campaign. When Sherman marched out of Atlanta headed for the sea, he had only the small division of Judson Kilpatrick with him. Sherman had the measure of the man, describing Kilpatrick as “a hell of a damned fool” in early 1864, and he ended up being right in his assessment. Kilpatrick did so poorly under Sherman (getting surprised and nearly captured three different times in a period of three months, including twice in his own camp) that by March 1865, Sherman was quite literally begging Grant to send him Sheridan with the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. Sheridan wanted no part of it, and refused to obey his orders to report to Sherman, leaving Sherman to fend for himself with only Kilpatrick’s small division for the entire Carolinas Campaign.

The retreads from the Army of the Potomac also did not do well in the West. I’ve already touched on Kilpatrick’s lackluster performance. Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, the original commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, was sent to Sherman and was captured while trying a harebrained raid intended to free the Union prisoners of war being held at Andersonville, Georgia. Instead of liberator, Stoneman ended up a prisoner himself.

One other factor should be considered here. In July 1863, the Cavalry Bureau was formed, with the specific mission of provided remounts for Federal horse soldiers who had lost their mounts. A system of relative efficiency developed, with remount depots. The main remount depot in the East was located at Giesboro Point, just outside downtown Washington, D.C. With the Eastern Theater’s actions and players concentrated within a hundred miles or so of Washington, it was relatively easy to develop an efficient system to deliver remounts. The sheer size of the Western Theater, with multiple armies scattered about, made the efficient provision of remounts a real challenge. A horse soldier often had to be gone for an extended period of time to get a fresh mount, thereby impacting the combat effectiveness of his unit.

The one clear exception to all of this was something that was clearly an experiment. Maj. Gen. James Harrison Wilson, another refugee from the Army of the Potomac, was nominally Sherman’s chief of cavalry in the winter of 1864-65. However, Wilson and the prickly Sherman evidently did not get along well, as Wilson was left behind to try an experiment. Wilson had a brilliant idea. He would create a mounted army, well armed and with good horses. This 15,000 man force proved to be the largest, best-mounted, and best-armed cavalry force of the war, and it thrashed Forrest and his men at Selma, Alabama in the spring of 1865. Wilson’s command is often called a prototype for modern armored tactics, and I can see where there were such statements come from.

Why was this force so successful? Excellent leadership, all of the technological advantages, and an effective remount system, combined with a well-defined mission. Once all of these factors converged, the result was that Wilson’s force became an unbeatable juggernaut that marks the ultimate evolution of Federal cavalry doctrine. However, these were hard earned lessons that took four years of war to learn.

I think that the synergy of all of these factors are the reason why the Union cavalry in the Western Theater never made the impact that it did in the East. Would anyone care to comment?

Indeed, I welcome your thoughts here. This is a question that I am often required to address, and it’s one I have invested significant amounts of time in trying to craft a coherent answer for.

Scridb filterGregg vs. Gregg

Notice: Use of undefined constant the_post_thumbnail - assumed 'the_post_thumbnail' in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/archive.php on line 65

In response to yesterday’s post, Todd Berkoff wrote, “There must have been some tension between John Irvin and his cousin David M. Gregg over that postwar appointment to the 8th US Cavalry. Like many people, we wonder why David M. Gregg left the service when he did…I tend to believe he couldn’t stand Sheridan’s ego any longer and refused to serve under him.” Stan O’Donnell echoed the sentiment, writing, “I’m wondering the same thing Todd is? You mentioned that Long John got command of the 8th US Cav in the post-war summer of 1866 and that David McM Gregg had covetted that same command. Is the implication that D MCM Gregg would have reentered the US Army had he been offered that particular command? Or am I interpeting that wrong?”

Let me address those two issues. I was originally going to respond in the comments section to yesterday’s post, but as I thought about it, I realized that there was enough of interest here to warrant a separate post. So, here goes…..

1. Regarding David M. Gregg’s resignation in February 1865: Gregg was very circumspect about the reasons, and never left any written evidence. His resignation letter says that he was resigning to take care of urgent personal business at home. The regimental surgeon of the 6th Ohio Cavalry, a man named Rockwell, wrote in a postwar memoir that he believed that Gregg was showing signs of what we today call PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, only Rockwell referred to it as Gregg’s nerves being shot. There is absolutely nothing to corroborate this, and I don’t believe it.

Here’s what I think happened.

First, I think that David Gregg was really miffed about being passed over for permanent command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps in the spring of 1864. He was the ranking officer after Pleasonton, and he had commanded the corps from time to time when Pleasonton was away. Instead, the high command brought in an infantryman to take command of the corps, and I think that it really pissed Gregg off.

Then, the infantryman, Sheridan, hung Gregg out to dry at Samaria (St. Mary’s) Church on June 24, 1864, leaving Gregg’s two brigades all alone to contend with 7 brigades of Confederate cavalry. Gregg lost about 25% of his command in several hours of very, very hard fighting and was lucky to get out with the remaining 75%. That he did is a tribute to his skillful fighting withdrawal. Sheridan never sent anyone to reinforce or cover Gregg’s retreat, and I think he was rightfully very angry about that.

A few weeks later, Sheridan was ordered to the Shenandoah Valley (August 8), and he left Gregg in command of the remaining cavalry forces remaining with the Army of the Potomac. Again, the appointment was not made permanent, and I think that just added to his growing frustration and anger.

One of David Gregg’s closest friends at West Point was his classmate, William Woods Averell. Averell was entitled to command the Army of the Shenandoah’s Cavalry Corps by seniority, but was passed over by Sheridan in favor of Gregg’s other classmate, Alfred T. A. Torbert, over Averell’s very loud protests. Then, when Averell wisely declined to attack Early’s entire army with three brigades of cavalry on high ground, supported by artillery, the day after the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, Sheridan unceremoniously fired Averell without any real justification for doing so. Averell was refused a court of inquiry, and that trashed his military career. His career was finished.

Then, in the winter of 1865, Torbert himself was fired by Sheridan as punishment for his failure to accomplish Sheridan’s objectives for a raid into the Luray Valley of Virginia intended to punish John S. Mosby and is guerrillas. Torbert was also unceremoniously relieved of command just about the time that Gregg began the process of resigning his commission.

By that time, it was clear that with the bulk of Early’s force having returned to the Army of Northern Virginia and only a scratch force remaining in the Valley, Sheridan would likely return to the Army of the Potomac. While I can’t prove this, I genuinely believe that he couldn’t bear the thought of serving under Sheridan again and that he found it so unpalatable that he preferred to resign his commission than to run the risk of being next in Little Phil’s crosshairs. Given what had happened to his two old friends and West Point classmates, I think it’s a completely reasonable fear/assumption, and is probably the best explanation for his actions.

2. The 8th Cavalry commission: Gregg’s family did not necessarily support his decision to resign; a favorite uncle told him straight out that it was a bad mistake. Gregg attempted farming and fruit growing, but was not good at it. He evidently missed the military, because in 1868, he applied for reinstatement so as to be considered for the command of the 8th Cavalry. Instead, the command went to his first cousin, Long John Gregg. David Gregg’s reaction is not recorded, and we don’t know for sure why the decision was made. I suspect that it probably did cause some tension between the Gregg cousins, but David was too much of a Victorian gentleman to leave behind any written evidence other than some very gracious statements praising Long John’s abilities, integrity, and courage under fire.

Again, we can speculate a bit. Let’s not forget that in 1868, when these events occurred, Grant was the commanding general of the armies, now with four stars. Sheridan was in command of troops in the west, fighting Indians. Sheridan always had Grant’s ear, and it wouldn’t surprise me a bit if Sheridan didn’t put the kabosh on Gregg’s reinstatement, reminding Grant of the circumstances of Gregg’s resignation in February 1865. Sheridan was that kind of guy, and Grant tended to listen to Little Phil, particularly when it came to the cavalry. Hence, I tend to think that this was Little Phil’s payback for Gregg’s resignation.

Or so I think.

Oh, yeah…one other interesting note about all of this….the lieutenant colonel of the 8th Cavalry during at least part of Long John’s tenure in command of the regiment was Thomas C. Devin, who had done such good service under John Buford. Devin was promoted to colonel and assigned to command the 3rd Cavalry, but fell ill with the cancer that took his life a few weeks later. Devin died in 1879, about the same time that Long John retired from the 8th Cavalry.

I hope that helps, guys.

Scridb filterNotice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: id in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Notice: Undefined index: std in /home/netscrib/public_html/civilwarcavalry/wp-content/themes/wittenberg/footer.php on line 8

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like