Category:

Union Cavalry

Today is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Ailken, South Carolina, wherein the still-feisty Confederate cavalry of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler set a trap for, and nearly destroyed a brigade of, Judson Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division. Kil himself barely escaped being captured. As a long-time student of Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign, this small but important battle has always fascinated me. It only lasted a few minutes, or I would have done something substantive with it years ago as a companion to my study of the Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads.

Today is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Ailken, South Carolina, wherein the still-feisty Confederate cavalry of Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler set a trap for, and nearly destroyed a brigade of, Judson Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division. Kil himself barely escaped being captured. As a long-time student of Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign, this small but important battle has always fascinated me. It only lasted a few minutes, or I would have done something substantive with it years ago as a companion to my study of the Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads.

My friend Craig Swain has an excellent post on the Battle of Aiken on his blog, which I commend to you.

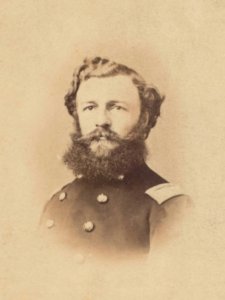

Scridb filter Robert H. G. Minty plays a critical role in my current book project, which is a detailed tactical study of the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga, September 18, 1863. Consequently, I have spent quite a bit of time studying him and his role in the Civil War since I decided to tackle the September 18 project, and was interested in him before the thought of tackling this project ever entered my mind. Minty is a fascinating fellow who had more than his share of foibles, but who nevertheless was one of the finest cavalry officers of the war. After the end of the Civil War, he abandoned his wife Grace and took up with her younger sister Laura in a very scandalous relationship. That tawdry story factors into the nonsense addressed in this post.

Robert H. G. Minty plays a critical role in my current book project, which is a detailed tactical study of the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga, September 18, 1863. Consequently, I have spent quite a bit of time studying him and his role in the Civil War since I decided to tackle the September 18 project, and was interested in him before the thought of tackling this project ever entered my mind. Minty is a fascinating fellow who had more than his share of foibles, but who nevertheless was one of the finest cavalry officers of the war. After the end of the Civil War, he abandoned his wife Grace and took up with her younger sister Laura in a very scandalous relationship. That tawdry story factors into the nonsense addressed in this post.

In a story that appeared on the website of WZZM, the ABC affiliate located in Grand Rapids, Michigan, two Michigan men make the outrageous claim that Minty stole $2 million in Confederate gold at the time that Minty’s cavalrymen captured Jefferson Davis:

Confederate gold treasure may be in Lake Michigan

ROOTS TO A CIVIL WAR MYSTERY – CONFEDERATE GOLD TREASURE – MAY BE IN LAKE MICHIGAN

Brent Ashcroft, WZZM

MUSKEGON, Mich. (WZZM) — Could there be roots to one of the Civil War’s most enduring mysteries in Muskegon, Michigan? That’s what two local treasure hunters strongly believe and they have four years of research that they feel proves it.

Kevin Dykstra and Frederick J. Monroe were diving in northern Lake Michigan in 2011 and found the remains of a shipwreck, they believe, could be “Le Griffon”, which sank in 1679. The funny thing is, the pair weren’t searching for shipwrecks at the time of their 2011 find.

They were searching for a much bigger treasure – lost Confederate gold from the Civil War.

Both Kevin and Frederick have decided to go public with their research, which reveals West Michigan could be home to this 150-year old mystery.

The beginning and the ending of this story starts and ends in Evergreen Cemetery in Muskegon. What unfolds in-between could lead to solving one of our country’s greatest mysteries.

“It’s a great treasure story,” said Frederick J. Monroe, an accredited scuba diving instructor and treasure hunter from Muskegon. “All the evidence is pointing toward right to what I’ve been told.” He first found out about the take from a friend in 1973.

“He brought to my attention about his grandfather on a deathbed confession,” said Monroe, who added that the individual offering up the death bed confession then said, “There’s $2 million of gold bullion sitting in a box car (at the bottom of Lake Michigan) and there’s only three people that know of it, and two of them were already dead.”

Monroe says that story has stuck with him for over 40 years and when he connected with Kevin Dykstra, he shared the story.

“I started to search and search,” said Dykstra.

His searching triggered a massive research project, which Dykstra believes reveals how the lost Confederate gold treasure found its way to Michigan nearly 150 years ago.

Civil War Gold Theft

STEALING $2 MILLION IN GOLD BARS

Dykstra says his research began when he learned that in 1892, boxcars were beginning to go across Lake Michigan on car ferries. He then discovered that some box cars were pushed off the ferries, during bad storms, to keep the ferries from sinking. At that point, he felt the death bed confession may have some merit, but more research was needed.“If there was $2 million of gold bullion at the bottom of Lake Michigan, it had to be missing from somewhere,” said Dykstra. “I needed to figure out where this gold was missing from.”

Dykstra started digging into the Confederate gold with Confederate President Jefferson Davis moving towards the south into Georgia after fleeing the Union troops in 1865.

“Some marauders got a hold of the gold at some point and stole it,” added Dykstra.

As he was researching this poignant moment in American history, Dysktra came across a name.

“I started focusing on one particular colonel; his name was Colonel Minty, who was actually in charge of the 4th Michigan Cavalry, who caught Jefferson Davis down in Irwinville, Georgia,” said Dykstra. “If Robert Minty had anything to do with the Confederate gold, he would have had to commit treason to take it,” added Dykstra.

Dykstra then uncovered that Colonel Minty was wrongfully court-martialed in 1864, ending his advancement in the military.

“Now, I have motive,” said Dykstra. He believes that Colonel Minty and his accomplices buried the Confederate gold treasure near Lincoln County, Georgia, which is where legend states it was buried.

Dykstra then began to research Robert Minty’s career after his military court-martial. He found that the colonel retired to Jackson, Michigan where he resumed working for the Detroit Railroad. Dykstra then followed Minty as he accepted several positions with other rail companies, leading him to eventually become superintendent of freight for the Atlantic and Gulf Railway, which was down in the southeastern corner of Georgia.

“The Atlantic and Gulf Railway passes right by where the gold was taken; I feel at this point, I have this man on the run,” added Dykstra.

So, in 1876, eleven years after the gold was stolen, Dykstra believes while working for the Atlantic and Gulf Railway, Minty dug the gold treasure up and began heading north with it, using the rail system. And then…

“I uncovered a horrible train accident in Ashtabula, Ohio,” said Dykstra.

Moving the Gold to Michigan

GOLD GOES MISSING AGAIN

On December 29, 1876, a railroad bridge in Ashtabula, Ohio collapsed, causing eleven boxcars to fall into a river gorge. 159 passengers aboard the train plunged into the river below. 92 were killed.

Dykstra says he found a newspaper article that stated that one of the box cars in the Astabula disaster was carrying $2 million in gold bullion.

“People flocked by the thousands to try to find that gold,” said Dykstra. “No gold was ever found.”

Dykstra found that Robert Minty may have been connected to this accident.

“Sure enough, [Robert Minty] was the superintendent of construction on that railway [at the time of the accident]”, said Dykstra. “I believe that Minty needed a diversion, so with his credentials, I believe that he started a rumor of the $2 million at the bottom of the river gorge to keep everybody away from the gold that was en route at the time.”

And then he discovered Confederate gold had been seen in Michigan.

“I came across another newspaper article that talked about a piece of Confederate gold that surfaced at a coin show in Traverse City; three experts looked at the piece of gold and confirmed that it only could have come from the Confederate gold that was taken down in Lincoln County, Georgia,” said Dykstra.

His research never led him to being able to place Colonel Minty, himself, in Traverse City, but Dykstra says he discovered the next best thing.

“Robert Minty married Grace Ann Minty,” said Dykstra. Her maiden name was “Abbott.”

The Abbott brothers and sisters were living in Traverse City when the Confederate gold showed up at the coin show. Minty would eventually also marry Grace’s sister, Laura Abbott, and had four children with her. These facts led him to one final connection, that he believes, points the finger at Robert Minty as the man who stole the Confederate gold treasure and was able to get it up to Michigan.

“[Robert Minty’s] mother-in-law’s name is Thomas-Ann Sutherland, and Thomas-Ann had a son named George Alexander Abbott,” said Dykstra. “George’s sister, Grace Ann Abbott, was married to Colonel Robert Minty.”

This means that George Alexander Abbott was Robert Minty’s brother-in-law.

“George Alexander Abbott died in 1921 and was the person who did the deathbed confession to the friend of Frederick’s grandfather,” said Dykstra. “The story goes complete full circle.”

Wow. Tawdry, shocking stuff if true. Too bad it’s all supposition and bears no resemblance to reality. I asked Rand Bitter, who published a biography of Minty that compiled Minty’s many articles that he wrote for publication in The National Tribune, a popular veterans’ newspaper, to comment on the article that appears above. Nobody knows more about Minty and his life than does Rand. Here’s his response, which Rand has given me specific permission to share with you here:

This has generated quite a bit of back & forth amongst some of the “Minty group.” Some in the family are quite upset with the slander and poor research supporting it. For your amusement (if interested), I will cut & paste below some of my own commentary on the matter from those other emails.

But first, before that, I calculated that “$126 million” of gold today, in their “sunken box car full” conclusion, calculates out to about 6,250 lbs -or over three tons. I just wonder how many wagons Jeff Davis was dragging along behind him (never mentioned in the accounts) just to flee with over three tons (or a box car full) of gold. And how long did it take, and how many of Minty’s (Pritchard’s) men were needed to unload and bury that much gold before they could set off for Macon with their prisoners that morning? Accounts only mention some gold coins found in the holsters of the escorts – and unlikely to account for three tons worth. Finally, why didn’t Davis himself ever complain of Pritchard’s appropriation of so much value???

Below are excerpts of some of my earlier email comments:

… I found two videos on USAToday site. Guess they have an ear for the sensational. That group surely did jump to some spectacular conclusions based on a collection of random and faulty “facts.” Indeed, RHG would have most certainly have made a leap for his pen, had he ever encountered such allegations and fabrication of history. Perhaps you should go ahead and advise Mr. Ashcroft that he is free to contact Minty’s biographer to “verify” some of them. He probably won’t though, and he will probably get a big raise for landing such a scoop.

I watched a second slightly different version of the video on the USAtoday site, and have to laugh at Mr. Dykstra saying “At this point, I have this man on the run” (referring to RHG and this scheme).

One more interesting question comes to mine. how do they know the gold is “in a box car” and why on earth would the box car have been on a ferry out in the middle of upper Lake Michigan (off Frankfurt)? That is not even on a route to any major destination across the lake, and nowhere near or towards anyplace that RHG had any interest in. And why would they push it off into the lake – just so the state of Michigan can “go and get your gold?”

… Decided to take a closer look at the video again this evening, pausing to look closer at the “research documents” shown therein and find it interesting that the image of Thomas-Ann Abbott shown in the groupings at video points 1:56 and later at 5:30, is a direct lift of the lower quarter of page 533 from my Minty book with my exact text caption. So the researchers must have come across a copy of the book somewhere and perhaps know of me.

… Thanks for the amusement for the day. It would be interesting if Mssrs. Brent Ashcroft, Kevin Dykstra and Frederick J. Monroe would pursue their research a bit further, and perhaps contact me to add some significant information. Thanks, Dani, for sending the articles and attachments [obituary, portrait, bio]. Let me add a few of my own comments and reactions:

1) Evidently [Minty brother-in-law] George A. Abbott made a deathbed confession [per his obituary] when he “died suddenly. “Mrs Abbott [being] in another room when she heard her husband fall, death having occurred instantly.” Interesting.

2) I believe that George probably held a grudge against Minty ever since [his sister] Grace was abandoned and they learned of the Laura situation in 1877. None of the Abbotts were too happy about the general or Laura thereafter.

3) The stories associated with Davis and the CSA gold never mentioned “bars” but rather coins. One account says Davis paid out some of the gold when he dismissed his confederate cavalry escorts a few days before his capture. Several other accounts mention that the renegade private James Lynch, who “possessed most of the coin” and took Mrs Davis’s valice and Pres. Davis’s horse (which he later shot when confronted by an officer) [see pgs 365, 370]. Several men mention Lynch as the thief of such things. One mentions Minty receiving a gold sovereign coin, from which a descendant says Grace had a necklace or pin made of it.

4) Court martial as a motive? Minty never really mentioned it much after acquittal – indeed he was later given brevet promotions to brigadier and major-general [not ending his military career], of which he seemed to care more about. To state “now we have motive” as the interview states, is pretty presumptive.

5) The Florida Atlantic & Gulf Railway (later Florida Central after 1868, then Jacksonville, Pensacola and Mobile in 1870s)? Minty was never employed by such a railroad, much less as “supervisor of freight.” In 1876 he was general superintendent of the SL&SE RR between Nashville and St. Louis. It is interesting, however, that during that time he was working with former General Wilson, under whose command Minty operated when Davis was captured. Also, Minty was never on a railroad that ran track through Georgia, Lincoln county or otherwise.

6) Ashtabula RR bridge disaster? That was in the far NE tip of Ohio in December 1876, the same time Minty was with the SL&SE in Nashville. He was not a construction superintendent with that Ohio RR (named Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway). Again, the researcher’s railroad data is quite faulty.

7) Confederate gold coin found in Traverse City? Well in late 1906, after Minty’s death, Grace was indeed in Traverse City, where several of her Abbott sisters were also staying. It may well be that Grace sold the gold coin necklace/pin due to poverty and needing the money. No descendant has mentioned seeing that item or knows of its disposition, so the story seems possible. In that period, Grace had very little means, and even all of her other children were still struggling financially.

8) If Minty had any access to the gold, it seems in light of his continuous financial difficulties, that he would have put some interest and effort into reclaiming it. The only really prosperous period in his life was the late 1860s in Jackson, where he was busy with several key railroad positions. There is no evidence that he ever had or knew anything about $2 million of gold in those days ($126 million today)! [the calculated 3.125 tons]

In light of what struck me as a flight of fancy when I first read the article–before consulting with Rand Bitter–and then in light of Rand’s comments, it seems clear to me that this claim is, at best, irresponsible and atrocious history and, at worst, libel. Whichever it is, anyone who runs across this nonsense should disregard it.

Scridb filter I found a fascinating publication while poking around on the Google Books site. Gen. Antoine Fortuné De Brack, a French cavalry general, published an outposting manual for use by the French cavalry. The third edition of his book was published in 1863, and was later translated and published by the United States Army in 1893. The introduction to this fascinating little volume contains General De Brack’s description of the importance of a light cavalryman:

I found a fascinating publication while poking around on the Google Books site. Gen. Antoine Fortuné De Brack, a French cavalry general, published an outposting manual for use by the French cavalry. The third edition of his book was published in 1863, and was later translated and published by the United States Army in 1893. The introduction to this fascinating little volume contains General De Brack’s description of the importance of a light cavalryman:

One must be born a light-cavalryman. No other position requires so much natural aptitude, such innate genius for war, as that of an officer of that arm. The qualities which make the superior man–intelligence, will, force–should be found united in him. Constantly left dependent on himself, exposed to frequent combats, responsible not only for his own command, but as well for that which he protects and guards, the employment of his physical and moral powers is continuous. The profession which he practices is a rude one, but the opportunities of distinguishing himself are presented daily–glorious compensation which the more richly rewards his labors by enabling his true worth to become the sooner known.

The French cavalry in the first half of the Nineteenth Century was the finest the world had ever seen, and this description is fascinating.

I can’t help but wonder whether Dennis Hart Mahan, who wrote the U.S. manuals for cavalry, was aware of this little volume and whether he incorporated it into his teachings.

Scridb filterI apologize for not having posted much recently. I’m deeply immersed in writing mode, working on my latest book project, which addresses the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga, September 18, 1863, with a particular focus on the covering force actions conducted by Col. Robert H. G. Minty’s Saber Brigade at Reed’s Bridge, and Col. John T. Wilder’s Lightning Brigade at Alexander’s Bridge. I’ve written about 120 pages so far, and it’s coming right along. But it’s been pretty much all-consuming.

Even in this age of easy access to digital research, you can’t get everything. Things get digitized too late to be of use. Or they don’t turn up in keyword searches. Or sometimes, you just plain miss things.

Even in this age of easy access to digital research, you can’t get everything. Things get digitized too late to be of use. Or they don’t turn up in keyword searches. Or sometimes, you just plain miss things.

Chief Judge Edmund A. Sargus, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio is not only a member of the Federal bench, he’s also very interested in the life and career of Capt. Thomas Drummond of the 5th U.S. Cavalry, a former U.S. Senator from Iowa, who was killed in action at the April 1, 1865 Battle of Five Forks. Judge Sargus brought a source to my attention that escaped me during both rounds of research for both editions of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions, and which I really wish I had had when doing them. Since I didn’t have them, but because they are so interesting, I want to share them with you here.

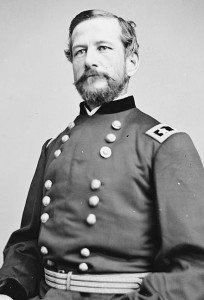

First is a letter by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, to Congressman (and former Brigadier General) John F. Farnsworth, the uncle of fallen Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth. Pleasonton’s toadying with John Farnsworth was largely responsible for the removal of Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel from command of the cavalry division that became the Army of the Potomac’s Third Cavalry Division not long before the Battle of Gettysburg (Stahel outranked Pleasonton and would have been entitled to corps command by virtue of that seniority). That toadying was also largely responsible for Elon Farnsworth’s promotion from obscure captain to brigadier general. After Elon Farnsworth fell leading the eponymous charge, Pleasonton sent this letter to John Farnsworth, who appears in the photograph below:

First is a letter by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, to Congressman (and former Brigadier General) John F. Farnsworth, the uncle of fallen Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth. Pleasonton’s toadying with John Farnsworth was largely responsible for the removal of Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel from command of the cavalry division that became the Army of the Potomac’s Third Cavalry Division not long before the Battle of Gettysburg (Stahel outranked Pleasonton and would have been entitled to corps command by virtue of that seniority). That toadying was also largely responsible for Elon Farnsworth’s promotion from obscure captain to brigadier general. After Elon Farnsworth fell leading the eponymous charge, Pleasonton sent this letter to John Farnsworth, who appears in the photograph below:

Headqrs. Cav. Corps Army of the Potomac

July 6th, 1863Gen. J. F. Farnsworth:

Dear General:

I deeply regret to announce to you the death of Brig. Gen. Farnsworth, late Captain 8th Illinois Cavalry. He was killed while leading a charge of his brigade against the enemy’s infantry in the recent battle of Gettysburg. His death was glorious. He made the first grand charge against the enemy’s infantry–broke them–when found, his body was pierced with five bullets, nearly a mile in rear of the enemy’s line.

He has been buried in the [Evergreen] Cemetery in Gettysburg, and the grave is properly marked. The enemy stripped the body to the undershirt–an unheard of piece of vandalism, as the General was in his proper dress.

Accept my warmest sympathy. You know my estimate of our late friend and companion in arms. We have, however, a consolation in his brilliant deeds in the grandest battle of the war.

Very truly yours,

A. Pleasonton

Pleasonton could afford to be gracious–the Army of the Potomac had won a major battle, and his cavalry had done well. And he owed a large debt to John Farnsworth.

Elon Farnsworth was wearing a brigadier general’s shell jacket lent to him by Pleasonton when he fell. Pleasonton was correct in saying that Farnsworth was “in his proper dress” when he fell.

The second letter was written by Capt. Thomas Drummond, which is why it caught Judge Sargus’ attention.

Gen. J. F. Farnsworth:

Gen.:

You have already heard of the death of your nephew, Gen. E. J. F., killed in the action on the 3rd. I was with him not five minutes before he fell, gallantly charging the the enemy’s infantry at the head of two of his regiments. His body was brought in last night, and at 3 a.m. of the day, I buried him with one of his captains, each in a good, rough box, in the Gettysburg Cemetery. He was shot through the pelvis, and had two balls through the left leg, one of which shattered his ankle.

Farnsworth’s loss is mourned by all. He had just got his star, and fell in a gallant endeavor to prove to his new men his right to wear it. While by the light of a single lantern I dug his grave, instinctively the lines of Sir John Moore’s burial at Corunna came in my mind.

“We buried him darkly at dead of night,

The sods with our bayonets turning,

By the moonbeam’s misty struggling light,

And our lanterns dimly burning.Slowly and sadly we laid him down,

From the field of his fame fresh and gory;

We carved not a line, we raised not a stone,

But we left him alone in his glory.”T. Drummond

Capt. and Prov. Marshal Cavalry Corps

John Farnsworth came to Gettysburg later that month to retrieve the remains of his nephew and to take them home to Rockton, Illinois, where they were buried in Rockton Cemetery. The photo to the left is the monument on Elon Farnsworth’s grave. You can see a larger version of this image by clicking on it.

John Farnsworth came to Gettysburg later that month to retrieve the remains of his nephew and to take them home to Rockton, Illinois, where they were buried in Rockton Cemetery. The photo to the left is the monument on Elon Farnsworth’s grave. You can see a larger version of this image by clicking on it.

Prior to seeing this source, I had never seen anything that said that Farnsworth had been shot through the pelvis, or that his ankle had been shattered by a ball. Given that he was mounted when shot by infantry, who had to aim high to hit him, it makes sense that these wounds would have been sustained in the bottom half of his body, and and that there would have been no evidence of him having shot himself in the head, as some claimed.

I’ve always claimed that Elon Farnsworth was the ONLY Union general to fall behind enemy lines while leading an attack during the entire Civil War, and Pleasonton bears out what I’ve always said. It really is a shame that the monument that the veterans of Farnsworth’s brigade had wanted to erect to him was not put up, as he is the only Union general officer to fall on the field at Gettysburg who does not have a monument of some sort to him on the battlefield.

Thanks to Judge Sargus for bringing this fascinating material to my attention. I only regret that I didn’t have it to include in my book.

Scridb filter With much gratitude to Al Eelman of Philadelphia, who was kind enough to share both this photo and the accompanying narrative with me. For a larger version of the photo, click the image.

With much gratitude to Al Eelman of Philadelphia, who was kind enough to share both this photo and the accompanying narrative with me. For a larger version of the photo, click the image.

I often tell the stories of forgotten cavalrymen. Today, I get to tell the story of a cavalryman’s horse, which is not something that I get to do very often. When I saw this photo and heard the story associated with it, I had to share it with you. Hence, I bring you this forgotten cavalryman story.

As some of you may know, a number of years ago, I edited and published a new edition of the memoir of the Appomattox Campaign written by Lt. Col. Fredric C. Newhall of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, who served on Phil Sheridan’s staff. After the Civil War, Fred Newhall returned home to Philadelphia, and in 1882, he wrote the following letter about his long-time companion, Dick, who served throughout the Civil War with him. Dick was a wounded combat veteran of many a campaign in the field:

DICK

HE IS 27 YEARS OLD THIS SPRING. HE WAS RAISED IN NEW JERSEY, AND IS OF THE “MAY-DAY” STOCK. I BOUGHT HIM 8MO. 1861 ON ENTERING THE ARMY, AND RODE HIM ALL THROUGH THE WAR. HE WAS IN MANY CAVALRY ENGAGEMENTS, AND IN ALL THE PRINCIPAL BATTLES OF THE POTOMAC, EXCEPT CHANCELLORSVILLE, AT WHICH TIME HE WAS WITH ME ON THE CAVALRY EXPEDITION, KNOWN AS THE “STONEMAN RAID” WHICH OCCURRED WHILE THE BATTLE OF CHANCELLORSVILLE WAS GOING ON. I RODE THIS HORSE ALSO IN GENERAL SHERIDAN’S CAMPAIGN IN THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY AND IN THE LAST CAMPAIGN AGAINST GEN’L LEE, WHICH TERMINATED IN VIRGINIA, IN THIS CAMPAIGN HE WAS WOUNDED IN THE LEG IN THIS BATTLE. ON THE DAY OF LEE’S SURRENDER AFTER THE REBEL FLAG OF TRUCE WAS DISPLAYED, I WENT ON THIS HORSE TO FIND GEN’L GRANT AND CONDUCTED HIM TO APPOMATOX COURT HOUSE TO MEET GEN’L LEE. IN MAY 1865 I TOOK THE HORSE WITH ME TO NEW ORLEANS, AND ON THE TERMINATIONS OF HOSTILITIES IN THAT REGION, I RESIGNED FROM THE ARMY, AND BROUGHT THE HORSE HOME WITH ME.

F C NEWHALL

Here’s to Dick, a grizzled and forgotten combat veteran of the cavalry service of the Civil War who did his duty quite well.

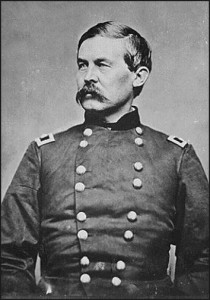

Scridb filter 150 years ago today, Maj. Gen. John Buford, the finest cavalryman produced by the Union during the Civil War, died of typhoid fever at the far too-young age of 37. The rigors of so many years of hard marching and fighting had taken their toll on Buford, who had contracted typhoid fever “from fatigue and extreme hardship,” after participating in the marches and fighting during the Mine Run Campaign that on November 7-8 compelled Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to abandon the line on the Rappahannock River and retire behind the Rapidan River. By November 16, he was quite ill. Buford was granted a leave of absence and removed to Washington, D.C., on November 20, 1863.

150 years ago today, Maj. Gen. John Buford, the finest cavalryman produced by the Union during the Civil War, died of typhoid fever at the far too-young age of 37. The rigors of so many years of hard marching and fighting had taken their toll on Buford, who had contracted typhoid fever “from fatigue and extreme hardship,” after participating in the marches and fighting during the Mine Run Campaign that on November 7-8 compelled Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to abandon the line on the Rappahannock River and retire behind the Rapidan River. By November 16, he was quite ill. Buford was granted a leave of absence and removed to Washington, D.C., on November 20, 1863.

There he was taken to the home of his good friend, General George Stoneman. Buford’s condition deteriorated quickly, and it soon became apparent that he would not survive.

On December 16, 1863, President Lincoln sent a note to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who was said not to trust anyone with southern antecedents, and who disliked most of the officers associated with John Pope’s Army of Virginia. Lincoln’s note requested that the gravely-ill Buford, whom Lincoln did not expect to survive the day, be promoted to major general. Although the promotion was well deserved, Stanton permitted Buford’s promotion only when it became certain that Buford was dying. The promotion was to be retroactive to July 1. 1863, in tribute to Buford’s service at Gettysburg. “Buford lapsed in and out of delirium, alternately scolding and apologizing to his black servant, who sat weeping by the general’s bed- side. He was comforted by several old comrades, including his aide, Capt. Myles Keogh, and General Stoneman. When the major general’s commission arrived, Buford had a few lucid moments, murmuring, “Too late. . . . Now I wish that I could live.” Keogh helped him sign the necessary forms and signed as a witness, and Capt. A. J. Alexander, 1st U.S., wrote a letter to Stanton for Buford, accepting the promotion. Buford’s last intelligible words–fitting for a career cavalryman–were, “Put guards on all the roads, and don’t let the men run back to the rear.” He died in the arms of his devoted aide and surrogate son, Keogh, on December 16.

Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt, Buford’s protege and the temporary commander of his First Division, prepared general orders:

His master mind and incomparable genius as a cavalry chief, you all know by the dangers through which be has brought you, when enemies surrounded you and destruction seemed inevitable…. The profound anguish which we all feel forbids the use of empty words, which so feebly express his virtues. Let us silently mingle our tears with those of the nation in lamenting the untimely death of this pure and noble man, the devoted and patriotic lover of his country, the soldier without fear and with out reproach.

The First Cavalry Division’s staff officers prepared resolutions of regret, lamenting Buford’s death and resolving that the members of the First Division would wear the badge of mourning for thirty days as a sign of respect for their leader. Another of Buford’s peers wrote in his diary,

December 20: The army and the country have met with a great loss by the death of . . . Buford. He was decidedly the best cavalry general that we had, and was acknowledged as such in the army. [He was] rough in his exterior, never looking after his own comfort, untiring on the march and in the supervision of all the militia of his command, quiet and unassuming in his manners.

In a tribute, the men of the First Division raised money to erect a monument to Buford at his grave site at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, a fitting final campground for a Regular. Most members of the 9th New York contributed a dollar each to pay for the monument.

Had Buford not fallen ill, he would have gone west to assume command of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Cumberland. The thoughts of a confrontation between Buford and Nathan Bedford Forrest boggles one’s mind, particularly since Buford’s first cousin Abraham assumed command of one of Forrest’s divisions in early 1864. Alas, it was not to be.

And so, we will leave it with the words of Buford’s dear friend, Maj. Gen. John Gibbon, who said, “John Buford was the finest cavalryman I ever saw.” What more needs to be said?

At Gettysburg, the Devil gave him a huge debt to pay, but Buford and his troopers did so magnificently. Here’s to Maj. Gen. John Buford, gone far too soon, but most assuredly not forgotten.

Scridb filter This is another forgotten cavalrymen profile that I’ve been working on for a while. This one features Maj. Jerome B. Wheeler, a man who led a fascinating life and who ultimately became both benefactor and scoundrel at the same time.

This is another forgotten cavalrymen profile that I’ve been working on for a while. This one features Maj. Jerome B. Wheeler, a man who led a fascinating life and who ultimately became both benefactor and scoundrel at the same time.

Jerome B. Wheeler was born in Troy, New York on September 3, 1841, the son of Daniel Barker Wheeler and Mary Jones Emerson. On his father’s side, he could trace his ancestry to British barons, while his mother was a cousin of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Both of his parents were originally from Massachusetts. The family moved to Waterford, New York while Wheeler was a boy, where he attended public schools until the age of 15. In 1856, he took a clerical job, and from 1857 to 1861, he worked as a tradesman, “which may have included engineering, mechanical, or machine shop work.”

Wheeler enlisted in the 6th New York Cavalry at Staten Island as a private for a term of three years on his 20th birthday. He stood 5’8″, had sandy colored hair, and grey eyes. He listed his occupation as “mechanic.” He was assigned to Co. D of the 6th New York. The next day, he was appointed corporal, serving with his company while the new troopers of the 6th New York learned their trade. “Filled with patriotism and and an earnest desire to learn all the duties of a soldier, I performed with the various duties of drilling, riding horses, bareback to water, with only a halter to hold them, being run away with, and receiving numbers of falls, but escaping serious injury, and performing other duties incident to camp life, I concluded that I was becoming a hardened soldier,” he recalled years after the war.

Late that fall, the 6th New York established its winter camp in York, Pennsylvania. On January 16, 1862, Wheeler was appointed battalion quartermaster sergeant. The regiment was ordered to report to Washington, DC in the spring of 1862, where it was mounted and then took the field. Wheeler was promoted to second lieutenant on October 27, 1862 after the 6th New York served at the Battle of Antietam. “Now I want you to earn it,” declared Devin when he handed Wheeler the commission, promptly sending Wheeler and a detachment of troopers behind enemy lines to insert a spy. Wheeler came under fire at the Battle of Fredericksburg and at Chancellorsville, and scrapped with Maj. John S. Mosby’s guerrillas in the spring of 1863.

Wheeler performed his quartermaster duties so well that by June 1863, he was acting as his brigade’s quartermaster. Col. Thomas C. Devin, who commanded the 6th New York until he became commander of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, knew Wheeler well, and used his talents wisely. When Brig. Gen. John Buford’s 1st Cavalry division made its historic stand at Gettysburg on the first day of the battle there, Wheeler was acting as Devin’s brigade quartermaster, and he had the important task of insuring that Devin’s small brigade, which had a long front to protect, had sufficient ammunition in order to give it a fighting chance to fulfill its mission.

On September 1, 1863, partially in recognition of his fine service during the Gettysburg Campaign, Wheeler was promoted to first lieutenant. During the October 1863 Bristoe Station Campaign, Mosby’s guerrillas attacked Wheeler’s wagon train in an ambush. The guerrillas captured the train, and Mosby was in the process of looting it when Wheeler mustered as many troops as he could and led a ferocious saber charge that recaptured the train, captured some of Mosby’s men, and set the rest of them running.

He served with distinction throughout the 1864 Overland Campaign. During the Battle of the Wilderness, he was ordered to report to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters and was given the task of getting an enormous wagon train of wounded men back through Fredericksburg to the Potomac River, and then to bring back supplies, all the while operating in hostile territory. He accomplished this task in record time, earning the praise of Grant. He served through Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, often having to contend with Mosby’s guerrillas while escorting wagon trains from place to place, and it was Wheeler’s orderly who was sent to Winchester during the Battle of Cedar Creek to inform Sheridan that his army was being shoved back from Cedar Creek by the enemy.

On January 16, 1865, Wheeler was promoted to captain, but remained in his role as quartermaster for Devin, who, by then, was in command of the 1st Cavalry Division. On February 26, his horse slipped and fell in Winchester, Virginia, pinning Wheeler underneath. “I was badly bruised and lamed,” he recalled, “and was carried into a house nearby. It was several days before I could be moved, and in the meantime the Cavalry Corps was out of reach up the [Shenandoah] Valley, and much to my disappointment and chagrin, I was obliged to return to Pleasant Valley, where the corps train had been ordered.” Hence, Wheeler missed the beginning of the Cavalry Corps’ march to join Grant’s army in the siege lines at Petersburg. Wheeler caught a train to City Point and arrived too late to join the Cavalry Corps’ last campaign. Wheeler’s April 1, 1865 return of service indicates that he was at Five Forks, Virginia, but he claimed that he was not present with the army when Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox. He participated in the Grand Review of the Army of the Potomac in May 1865, and was then the 6th New York was ordered to report to Louisville, Kentucky, where it spent a pleasant summer. Wheeler and the rest of the regiment mustered out on September 5, 1865.

Although his service records do not indicate as such, he was breveted to major at some point in late 1864. One account of his life states, “late in the war, he was promoted to the rank of colonel, but his commanding officers reputedly revoked the promotion due to to a breach of discipline.” Nothing in his service records supports this claim, but has been repeated numerous times over the decades since the end of the war. One account of his life indicated, “Wheeler was cited repeatedly for ‘outstanding courage in the field’ but was broken from his rank of Colonel for disobeying orders…he led a supply train through enemy Confederate lines to an encircled and starving Union regiment.”

“During [Jerome’s] service on the brigade and division staff he was always at the front, even when his duties did not call him to the post of danger; and his zeal, tempered always as it was by good judgment, was not surpassed by that of any of those with whom he served,” declared Capt. William L. Heermance of the 6th New York Cavalry, himself a Medal of Honor recipient.

He mustered out of the army in September 1865, and returned home to Troy, New York, where he took a job as a bookkeeper, a position where his quartermaster skills served him well. He remained in Troy for about eight months and then moved to New York City, where he took a clerical position with a prominent grain merchant firm. He stayed there for two years before taking a position with Holt & Company, one of the largest grain brokers in the city. He spent ten years there, working his way up to a full partnership position by 1878.

In 1870, Wheeler married Harriett Macy Valentine, whose family owned a dry goods store in New York City called R. H. Macy, which still exists today as Macy’s. By 1870, R. H. Macy was a full department store and was the largest and oldest retail store in the city. Harriett’s uncle Rowland Macy, who ran the family business, developed a fatal kidney disease called Bright’s Disease (which also claimed the life of Judson Kilpatrick). Rowland Macy’s son, Rowland, Jr., was a dissipate young man, and Rowland Macy did not believe he was capable of running the family business. Instead, the operations of the company ended up in the hands of young man named Charles B. Webster, who was too inexperienced to run the business effectively. Webster approached Wheeler to join him in running the company, and Wheeler purchased stock from a family member and began his tenure as a partner in the venture.

From 1879-1888, Wheeler ran the affairs of Macy’s as president and 50% partner, leading the company to record sales and profits. In 1882, Wheeler and Harriett visited Colorado, seeking a cure for Harriett’s severe bronchitis. Wheeler was instantly smitten by the rugged beauty of the place. They visited Manitou Springs, and famous for its mineral waters, and built a summer home there. He started the Manitou Mineral Water Company, which was very popular back east, and was served at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. While residing in Manitou, he heard of silver strikes in nearby Aspen and caught mining fever. Before long he had purchased interests in a number of silver mines, and sold his interest in Macy’s in 1888 in order to focus on silver mining.

Wheeler also organized the Grand River Coal and Coke Company to provide coal to smelt ore and to fire railroad engines. He also founded the Aspen Mining and Smelting Co. to smelt the ore from his mines. He promoted and invested in the Colorado Midland Railroad and settled in Aspen, high in the Rocky Mountains. He founded a bank, built the Wheeler Opera House, and The Hotel Jerome in the newly affluent town. He also owned two other banks and a marble quarry. Before long, he was phenomenally wealthy. He invested nearly $6 million into developing Aspen, and is remembered fondly and as an icon there as a result.

“In a time of robber barons, Wheeler was a benevolent giant of industry,” recalled one biographer. “Looking out for the welfare of others was a lifelong trait. He paid the way for many a young artist to study in Europe, he supported families that had no claim on him other than his sympathy. When the silver crash did come, he sent cattle and potatoes to feed starving families.” Unlike the robber barons, Wheeler is remembered fondly as a good man who gave much back to the community that he helped to found.

But his wealth did not last.

The demonitization of silver in 1893 doomed his silver mining operations and the businesses that depended on those silver mines. His banks in Aspen, Manitou, and Colorado City failed and were forced to close, but Wheeler paid his depositors every dollar, and they lost nothing.

All along, Wheeler had been the patron of a gifted sculptor in New York City neared James E. Kelly. He subsidized many of Kelly’s projects, and when the Buford Memorial Association was formed to erect a suitable monument to Wheeler’s old commander, Maj. Gen. John Buford, Wheeler paid the bulk of the nearly $4000 cost of the handsome monument that was finally dedicated on McPherson’s Ridge on July 1, 1896.

All along, Wheeler had been the patron of a gifted sculptor in New York City neared James E. Kelly. He subsidized many of Kelly’s projects, and when the Buford Memorial Association was formed to erect a suitable monument to Wheeler’s old commander, Maj. Gen. John Buford, Wheeler paid the bulk of the nearly $4000 cost of the handsome monument that was finally dedicated on McPherson’s Ridge on July 1, 1896.

In 1892, Wheeler became embroiled in the first of a series of lengthy and costly lawsuits over one of the silver mines that ultimately ruined him. Most of these suits were from investors in the silver mining operations who claimed that they had been defrauded. In 1893, he lost a lawsuit and had a judgment of $800,000 taken against him. He lost several other cases associated with his silver mining activities, and was financially ruined. The combination of the judgments and the economic recession of 1893 caused by the crash of the value of silver cost Wheeler nearly his entire fortune. He lost The Hotel Jerome and Wheeler Opera House to back taxes, and in 1903 was forced to declare bankruptcy in the courts of New York.

He died in Manitou Springs on December 1, 1918, still trying to regain ownership of the Wheeler Opera House. Jerome B. Wheeler was buried on June 26, 1919 at Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx, New York, Cypress Section 47, Lot 5486-90. The Wheeler Family plot is marked by a beautiful monument of his son, Clarence Wheeler, by James E. Kelly.

He died in Manitou Springs on December 1, 1918, still trying to regain ownership of the Wheeler Opera House. Jerome B. Wheeler was buried on June 26, 1919 at Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx, New York, Cypress Section 47, Lot 5486-90. The Wheeler Family plot is marked by a beautiful monument of his son, Clarence Wheeler, by James E. Kelly.

Jerome B. Wheeler left behind a truly mixed legacy. Part hero, part insubordinate officer, part patron of the arts, and part swindler, Wheeler marks the best and the worst that the Gilded Era had to offer. The modern city of Aspen, Colorado owes much to Wheeler, and he is largely responsible for the erection of the handsome monument to John Buford that stands atop McPherson’s Ridge. But many lost everything as a result of his business dealings, and he lost everything he had made of himself as a consequence of his own overarching greed. His life is a cautionary tale of rags to riches to rags once again.

Here’s to Bvt. Maj. Jerome B. Wheeler, forgotten cavalryman. With my thanks to William B. Styple for his assistance in locating Wheeler’s gravesite and for the image of the monument to Clarence Wheeler.

Scridb filterIn October 2006, I did an extremely abbreviated Forgotten Cavalrymen profile of Col. William H. Boyd, the commander of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry. When I did that post, I lamented how difficult it was to locate usable material on Colonel Boyd. Sadly, things remained that way for seven long years. Finally, though, thanks to Barbara Chaudet, who provided me with much of the information that I needed to flesh out this profile, I can finally put some real meat on those bones.

Here’s a full profile of this heroic, forgotten cavalryman:

William Henry Boyd was born in Montreal, Canada on July 14, 1825. His father was a soldier in the British army. “From early boyhood, he was self-reliant and ready to do for himself. He was traveled in the four quarters of the globe,” recalled a friend. “He has been sent upon missions of importance in early manhood and carried them through with credit. He has held places of trust and been faithful.” At the age of twenty, he settled in New York City, where he went into the business of publishing city directories. His city directory business–called Boyd’s Directories–was similar to a modern telephone book. It provided listings and information about businesses and individuals. “He has followed up a special branch of business, in which he might be called a pioneer, and in which he worked hard enough and long enough to have been counted among the millionaires; but, like so many others with a similar nature, he was confiding, and trusting, and generous, and so others often reaped where he had sown.”

He married Elizabeth S. Watson in 1845, raising a family of five daughters and two sons, including William H. Boyd, Jr., who served with him in the Civil War, and nine grandchildren.

With the coming of war in 1861, he was operating his directory publishing business in Philadelphia. Boyd had the honor of recruiting THE first company of volunteer cavalry raised in the Civil War. He personally recruited and mustered Company C of the First New York (Lincoln) Cavalry in Philadelphia on July 19, 1861. He was elected captain and thus had the honor of being the first volunteer captain of cavalry sworn in. He and his men went to New York to join their regiment, which arrived in Washington, DC on July 22 and was mounted and equipped two days later. These raw horse soldiers were ordered to report for duty without having had any training to speak of, but found themselves on a mounted reconnaissance near Mt. Vernon on August 18, 1861. They encountered Confederate cavalry near Pohick Church, and Boyd ordered the first charge of volunteer cavalry. He was complimented by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan in front of the troops at a review held on August 22, and again on December 5, in Special Order No. 170.

“He was a brave soldier and faced anything he encountered,” recalled his eulogist. “He never forgot to be a humane man, and he was well known throughout the Shenandoah Valley and other sections, as a kind military man. When he necessarily came in contact with the households of those who favored the other side, or whose men were in that service, he respected their helpless situation and remembered that they were of his own mother-sex and needed this honorable treatment.”

Boyd was appointed provost-marshal on December 1, and his company served as provost guard for Gen. William B. Franklin’s division, serving with Franklin throughout the Peninsula Campaign. He was relieved of that duty on August 4, 1862, and joined his regiment, which had reported to Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside at Falmouth, VA on August 14. The 1st New York Cavalry then reported to Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s cavalry division of the Army of the Potomac on September 5, 1862, just in time to participate in the Maryland Campaign, which was already underway. Boyd participated in the Battle of Antietam, and helped to lead a charge of the whole regiment at Williamsport, MD on September 19.

On September 28, Boyd was assigned to western Virginia to chase after guerrillas and bushwhackers. In October, at Capon Bridge near Winchester, he captured several of Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden’s artillery pieces, twenty wagons, eighty mules, 100 horses, a major, a lieutenant, and 30 enlisted men. The 1st New York remained there until December 12, when they were sent to join Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy’s command in the Shenandoah Valley, leading to a promotion to major. The Lincoln Cavalry spent most of the spring of 1863 chasing the guerrillas of John Singleton Mosby. That spring, Boyd led an expedition to The Plains, in the Loudoun Valley, in an attempt to capture Mosby in his bed, when an informer told him that Mosby was visiting his wife there. All of Mosby’s clothing but his boots were there when Boyd entered the house (Mosby went out a window and was hiding in a tree), and Boyd interrogated Pauline Mosby about here husband’s whereabouts.

On June 13, 1863, during the Second Battle of Winchester, Boyd engaged in hand-to-hand combat with Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins’ troopers, and then led his command out of the trap laid for it at Winchester by the Army of Northern Virginia when he was ordered to carry important messages to Martinsburg. From Martinsburg, he escorted Milroy’s wagon train to Harrisburg, PA, arriving on June 17. Boyd and his troopers then rode to Greencastle, PA, where they engaged Jenkins’ cavalry on June 22 (Cpl. William Rihl of Philadelphia was killed in this skirmishing with Jenkins, making Rihl the first Union soldier killed north of the Mason-Dixon Line during what we now know as the Gettysburg Campaign). Boyd and his little band dogged Jenkins’ command all the way to the banks of the Susquehanna River and then back in the direction of Gettysburg, seldom escaping from the saddle for more than a few minutes. They were in the saddle almost constantly from June 12-July 12 and remained in constant contact with the enemy the entire time.

As a reward for this remarkable service, Boyd was commissioned colonel of the newly-formed 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry in August 1863. After the new regiment mustered in, it received orders to report to the Shenandoah Valley, where it remained for the winter of 1863-1864. In May 1864, his regiment was ordered to report to Washington, DC. He was then ordered to dismount his men, whom were then armed with infantry weapons. After some time to drill, Boyd and his regiment (which, although still designated as a cavalry regiment, was now serving as infantry), arrived at the front on June 1, 1864. On July 3, they participated in Grant’s great assault at Cold Harbor, where Boyd and his men came under heavy infantry and artillery fire. Colonel Boyd received a severe wound to the neck that left him disabled and unable to resume the field for the balance of the war. The ball Confederate ball pierced his neck and lodged in one of the vertebrae, where it remained for five months and was only extracted after three unsuccessful attempts, leading to a medical discharge for disability in November 1864 as a result.

When he left the service, he took up residence in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. In recognition of his kindness to the people of the Shenandoah Valley, when Brig. Gen. John McCausland’s cavalrymen burned Chambersburg in July 1864, McCausland posted guards around Boyd’s residence to protect it, demonstrating the respect in which the enemy held him.

Notwithstanding his military service, Colonel Boyd continued publishing his city directories, and with the assistance of his sons and sons-in-law, published the directory in Washington, D.C. throughout the war, missing only one year. He settled in Washington after the war, and resided there for the rest of his life. In 1868, he was appointed an agent of the Treasury Department, and held that position for some years. Boyd’s “life was a busy and eventful one, and he was highly respected by the entire community,” recalled one observer. He was a member of Calvary Baptist Church.

“Colonel Boyd was a great pedestrian,” observed a biographer, “and it is said that in 1854, he made a mile in six minutes and forty-two seconds, which it is claimed has never been beaten.”

In 1869, Boyd and John S. Mosby met, and after an ugly exchange of words, Mosby challenged Boyd to a duel. Boyd was apparently serving as sheriff of Fauquier County, Virginia after having been appointed to the post, and the possibility of a duel proved to be tantalizing to the public, given Mosby’s fame as a guerrilla. The duel never occurred, but the two men engaged in a lengthy war of words in the local newspapers. For those interested in learning more about this interesting episode, click here, where the complete interviews with both Boyd and Mosby can be found. It is not known precisely how long Boyd served as sheriff of Fauquier County.

Boyd died on October 7, 1887, and was buried in Glenwood Cemetery, in Washington, DC. “He had suffered intensely the last three weeks and was unconscious when he died,” noted one obituary. His entire family was with him when he died. A number of his old comrades in arms attended the funeral.

William H. Boyd is a particular favorite of mine, both for raising the first company of volunteer cavalry in the Civil War, and also for his heroic service during the Gettysburg Campaign. He suffered a severe wound while doing his duty, and was an honorable man. Here’s to this forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filter This announcement was passed along to me today:

This announcement was passed along to me today:

The Phil Sheridan Society

Perry County Historical and Cultural Arts Society

Somerset, OhioThe Perry County Historical and Cultural Arts Society are proud to announce the formation of the Phil Sheridan Society to help promote an understanding of the many aspects of the Civil War. The Phil Sheridan Society is dedicated to not only promote the history of the Civil War but to also promote the legacy of General Phil Sheridan. To accomplish this The Phil Sheridan Society is having a lecture series encompassing all different topics of the Civil War.

The public is cordially invited to attend all of the lectures and any events put on by The Phil Sheridan Society! The lecture series will commence on September 28, 2013, with a discussion by John Dye on Civil War medicine. The group will have a social hour at 6:30 pm at the Somerset Courthouse with the lecture starting at 7:30 pm. There will be a small $ 5.00 fee for the public or they can purchase a lecture series membership which will allow them access to all of the lectures for free. This is done to help offset some of the costs for the speakers so that the public will have access to some of the premier Civil War authorities within the state and the nation. The Phil Sheridan will meet on the last Saturday of the month with the lecture series lasting from September 2013 to May of 2014. Some of the other topics will include Morgan’s Raid in Ohio, Ohio’s Forgotten Civil War Generals, Ohio’s wartime governors, Medal of Honor Winner Milton Holland, Abraham Lincoln, Nellie Sheridan, and of course, Nellie’s famous son Phil Sheridan!

If you wish to get more information on The Phil Sheridan Society feel free to contact Craig Phillips at cphill17@columbus.rr.com with any questions.

I’m just guessing, mind you, but I’m thinking that they won’t be asking me to come speak to their group any time soon….. 🙂

Scridb filter I had quite a rare treat today. Sharon McCardle, who is an officer of the Rockton, IL Historical Society, stopped by my office to visit. Sharon and her husband Karl had been in Gettysburg at the conference of the Company of Military Historians, where she set up a prize-winning exhibit on Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth. Farnsworth’s charge and death are the cornerstone of my book Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions: Farnsworth’s Charge, South Cavalry Field and the Battle of Fairfield, so he’s long been of great interest to me.

I had quite a rare treat today. Sharon McCardle, who is an officer of the Rockton, IL Historical Society, stopped by my office to visit. Sharon and her husband Karl had been in Gettysburg at the conference of the Company of Military Historians, where she set up a prize-winning exhibit on Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth. Farnsworth’s charge and death are the cornerstone of my book Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions: Farnsworth’s Charge, South Cavalry Field and the Battle of Fairfield, so he’s long been of great interest to me.

Sharon brought a number of very cool items for me to see, but none cooler than Farnsworth’s saber–the one he was carrying when he was killed. I’m holding it and its scabbard in the photo. I’ve only had one cooler photo of me taken, which is of me holding John Buford’s Henry rifle, taken many years ago.

That’s Sharon in the photo with me. What a very neat thing to experience. Thanks to Sharon and Karl for coming to visit and giving me such a neat memory to savor.

Click on the photo to see a larger image.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like