Month:

March, 2008

We’re watching a modestly interesting documentary on the History Channel called “Axe Men”. It’s about lumberjacks in the Pacific Northwest. Once I got beyond wondering when they would sing Monty Python’s Lumberjack Song (they didn’t, by the way), I started wondering about a much bigger and more important question.

We’re watching a modestly interesting documentary on the History Channel called “Axe Men”. It’s about lumberjacks in the Pacific Northwest. Once I got beyond wondering when they would sing Monty Python’s Lumberjack Song (they didn’t, by the way), I started wondering about a much bigger and more important question.

This is a routine documentary on contemporary events, the sort of thing that has long been the staple of the Discovery Channel or the National Geographic channel. It’s NOT history. What is this doing on the History Channel? Or “Ice Road Truckers”? Again, interesting, but not history.

I can remember a time when the History Channel actually showed quality history programming. It carried the excellent “Civil War Journal” series. It has done some really interesting programming on the presidents of the United States. Or “History’s Mysteries”, another favorite of mine. There was a time when this channel was history, 24/7/365, and that’s what made it unique. You could always find something that was purely historical and often really interesting on the History Channel.

Now, it’s the UFO/paranormal channel, with lots of of programs about Adolf Hitler and Nostradamus, and these stupid documentaries that have nothing to do with history. Now, I completely understand that television programming is a business and that networks are going to air what makes money for them. I get that. It makes sense.

Here’s the description of another new series:

Gangland, the new series on The History Channel, takes you inside prisons and on the streets of America to view the most violent and influential gangs in our modern times.

The key to that description is the word “modern”. Again, it’s contemporary stuff and NOT history.

However, why not just be honest about it and give up the charade that this is still supposed to be a network that carries legitimate, serious programming about history. Just change the name and stop defrauding the public as to the nature of the content by calling yourself a “history channel” when it is now far, far from being that.

I miss the real History Channel, and I despise the crap that has taken its place.

Scridb filterBecause of its geographic location, Columbus typically does not get big snow storms. What usually happens is that it will start out as snow and then switch over to sleet or freezing rain (what I generally describe as slop) and sometimes to just plain rain. We’re usually just a little too far east to get all snow and a little too far west to get all rain. Here’s a good example. In December 2003, just a couple of days before Christmas, we had a storm that started out as snow–about 8 inches–and then turned to freezing rain. When it was all said and done we had 2.5 inches of ice on top of the snow and no power for nearly four days. The rain/snow line was about 20 miles west of us.

For a change, this time, the storm went right up the spine of the Appalachians, meaning that the rain/snow line is about 75 miles east of Columbus. The White Death From Above began falling yesterday morning about 9:00 and came down steadily until about 7:00 P.M. We had five or six inches of snow and then it stopped for a few hours before phase two of the storm came along during the night.

As I write this, we’ve had at least a foot of the White Death From Above, and we’re under a blizzard warning for the rest of the day. We’re looking at another several inches of the White Death before it ends. This is, without question, the biggest single snowfall that has occurred in the 20+ years that I have lived here in Columbus. Pretty much everything in our county is shut down at this point and they’re trying to keep people off the roads. Watching the dogs trying to negotiate their way through the White Death is quite humorous.

The snowdog laying down is Aurora. She’s two. The one running through the snow is Nero, who’s three. They’re loving this stuff.

I’ve had quite enough of the White Death From Above and am eager for spring to come. Of course, with it being March, it’s supposed to be 50 on Tuesday, meaning that all of this will turn to slop in no time flat. Spring cannot come soon enough.

UPDATE, 12:30 PM: I just was out in the yard with the dogs–I made the mistake of throwing one of their toys out there, and it was a real challenge getting them back in the house with the toy–and we’ve probably got 14-16 inches of White Death in the backyard. And it’s the dry, light, fluffy stuff. Like I said, spring cannot come soon enough.

UPDATE, 6:15 PM: The White Death From Above finally seems to be tapering to an end. We have approximately 18 inches of the stuff here at our house. The official records are set at Port Columbus International Airport, and the airport marked 20 inches of total snowfall, shattering the all-time record for a single storm since records have been kept here. We’ve now got blowing and drifting. Lots of fun. I hereby vote that the rest of winter be canceled due to lack of interest.

This photo is looking down my driveway at the street. You can’t tell where the driveway ends and the grass begins because it’s under more than a foot and a half of snow.

Scridb filterIt’s been a while since I’ve profiled a forgotten cavalryman, so I thought it was high time that I did so.

Bvt. Brig. Gen. William Emile Doster was born on January 8, 1837, at the Moravian town of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His father, Lewis Doster, a native of Swabia, Germany, served a campaign against Napoleon, and emigrated to America with his father, Doctor Daniel Doster, in 1817, at the age of twenty. His mother, Pauline Louise (Eggert) Doster, was the daughter of Matthew Eggert, at one time Vorsteher of the Brethren’s House, and granddaughter of Adam Rupert, a soldier of the Revolution. His father owned and operated the successful Moravian Woolen Mills in Bethlehem.

As a child, he preferred drawing and painting, but as the seventh son, as his grandfather before him had been, he appeared destined for the profession of medicine. However, he did not like medicine or have any interest in pursuing it as a career. William attended the Moravian school until the age of fourteen, and after a careful preparatory training entered the sophomore class of Yale College, graduating in 1857. In 1859 he graduated as LL.B. at the Harvard Law School. In 1860 he matriculated as student of civil law, in the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and heard lectures on the Code Napoleon in Paris.

Upon his return home he apprenticed with ex-Governor Andrew H. Reeder, at Easton, and was admitted to practice at the Northampton County bar. Aside from fencing and riding, taught in the European universities, he had no military training.

When the war broke out he was in the office of S. Van Sant, of Philadelphia, but putting aside briefs and black letter-books, he responded to the President’s call for volunteers, and recruited a company of cavalry, which, not being wanted for that arm, was turned over to Colonel Edward D. Baker’s infantry regiment. Doster then raised another company for Harlan’s Light cavalry, of which he was made Captain, his muster bearing a date of August 15th, 1861. A few weeks later this company was transferred to the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

On October the 28th of October he was promoted to Major, and a little more than a month later, was detailed with a squadron to act as bodyguard to General Erasmus Keyes.

Toward the close of February, 1862, he was placed in command of the mounted provost guard of Washington, D. C. When the Army of the Potomac departed for the Peninsula, and the appointment of General James S. Wadsworth as Military Governor of the District, Colonel Doster was selected for Provost Marshal, giving him command, by detachment, of four infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment, together with a flotilla cruising upon the Chesapeake.

In October, 1862, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, but continued at his post as Provost Marshal. Just previous to the opening of the spring campaign of 1863, he applied for an order to return to his regiment, which was granted, and was coupled with a recommendation from General Wadsworth to President Lincoln, for his appointment as Brigadier General. On rejoining his regiment he assumed command, and led it during the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns. He had his horse shot under him at Ely’s Ford, and in a charge which he led at Upperville, was taken prisoner. However, in less than an hour, Doster escaped by striking down his guard and returned to his command.

At Gettysburg he was ordered to report with his regiment to General Pleasanton, at General Meade’s headquarters. On the afternoon of July 2, the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry was the only regiment sent to take position on the Federal left flank, meaning that one regiment was supposed to provide the same coverage as the provided by two brigades of Brig. Gen. John Buford’s division. That evening, Doster was ordered to picket duty on the left flank, and established a line in front of the infantry at eleven o’clock that night. On July 5th, he was ordered to advance through Gettysburg in pursuit of the enemy.

Tearing aside the barricades that obstructed the way, he pushed on as far as Stevens’ Furnace, where he engaged the rebel rear guard. By the evening of the 6th, he had reached Marion, near Greencastle, where he struck Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry. After a severe action brought on by reconnoitering towards Winchester, he led his regiment back to the Rappahannock, where he was prostrated by malaria. Too ill to return to duty, he sent in his resignation, which was accepted. He returned home to Easton and was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar. However, soon after, he was appointed colonel of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry, but never joined the regiment. He was subsequently brevetted brigadier general of volunteers.

Doster practiced law in Washington for a short time, and at the trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, he was appointed, by Judge-Advocate-Generals Hold and Bingham, to defend Lewis Payne and George Atzerodt, two of the defendants. Both were convicted and hanged.

Soon after the close of the war he returned to Northampton County and resumed the practice of the law at Easton, residing at Bethlehem. From 1867-1879, he held the office of Register in Bankruptcy for the Eleventh Congressional District. He was also the long-time president of the Lehigh National Bank and also of the New Bridge Street Company.

On August 15, 1867, he married Evelyn A. Depew, daughter of Edward A. Depew, of Easton. They had one son. The couple settled in Bethlehem in 1873. Doster traveled to Europe more than 30 times in the years after the Civil War.

In 1891, Doster published his Brief History of the Fourth Pennsylvania Cavalry, following it in 1915 with his memoirs, Lincoln And Episodes Of The Civil War.

Doster died on July 2, 1919, and was buried in Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem.

Scridb filterThere have literally been thousands of books written and published about the Civil War, perhaps even tens of thousands. Thus, the field is quite full when trying to determine which are the 50 greatest Civil War books ever written. To make such a list is quite an honor indeed. It means that a book is in the 99th percentile of all published books on the Civil War.

The good folks at Civil War Interactive polled their readers to determine the 50 best books on the Civil War. 621 people cast 1863 votes to create the list. The results of that poll can be found here.

The likes of Douglas Southall Freeman, Shelby Foote, Stephen W. Sears, and Bruce Catton appear often on this list. Some appear more than once. Great classics like Battles and Leaders of the Civil War and the Official Records also understandably appear on the list. I was genuinely shocked not to find any of the four volumes of Gordon Rhea’s epic, groundbreaking study of the 1864 Overland Campaign–some of the finest campaign studies ever written, in my humble opinion–on that list. Thus, I was flabbergasted to find J.D.’s and my Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg sitting at number 50 on that list. It seems we’re in some very, very good company here.

I don’t especially enjoy tooting my own horn, and I never think of my work as being of that caliber. Given that the quality of research and writing found in Gordon Rhea’s work is that standard that I strive to match, I just don’t, look at my work that way as that’s a high standard to meet indeed. Consequently, I am always amazed when my work gets that sort of recognition because I just don’t think of it that way. Accordingly, when I found our work in such esteemed company, I was stunned, flattered, and humbled all at the same time.

All I can say is thank you for the honor bestowed upon our work, and can also say that I can only hope that I continue to live up to your expectations with my future work. Thank you.

Scridb filterThose of you who’ve read this blog for a long time know that in addition to my addiction to the Civil War, I am an ice hockey, NFL football, and baseball nut. Having grown up in the Philadelphia suburbs, I am well acquainted with the concept of losing. During my childhood, both the Eagles and the Phillies were atrocious. And then there was the 1973 Philadelphia 76’ers, who posted a 9-73 record, the worst record ever in the history of professional sports.

As a child, one of my very favorite books was the 1974 edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia. I would spend hours and hours going through that book reading statistics and learning about long-gone players that I had never heard of previously. In the process, I learned about some great teams and great players, but I also learned about some atrocious teams, too. With as bad as the Phillies were–in 1972, they were 54-108–I came to embrace the love of bad, losing teams. Consequently, I came up with an idea that I have always wanted to pursue but never had an opportunity to do anything with.

As a 13-year-old, I devised the idea of doing a study of the worst teams in the history of Major League Baseball, which I wanted to call The Losers. I picked out some teams and thought it would be fun to do the research for a project like this. The all-time worst team in the history of Major League Baseball was the 1899 Cleveland Spiders, which didn’t even make it all the way through the season. They went 20-134 and had to play their last 35 or so games on the road, because no National League team would come to their field to play due to no attendance. Or then, there were the 1930 Phillies, who had a team batting average in excess of .310 and a team ERA well over 6.00, meaning that even with that kind of offense, they finished dead last in the National League. Or the St. Louis Browns, who went to the World Series once in their history. Or the Washington Senators who went once, in 1924. It just seemed like a project that would be a blast.

I put this idea away years ago, never figuring I would get a chance to do anything about it. I just didn’t have the resources or knowledge how to do that sort of research, and I always had other projects.

Fellow blogger Michael Aubrecht has done a great deal of writing on baseball over the years for Baseball Almanac. He knows how to do this sort of research and also knows how to write about baseball. In the course of a few exchanges of e-mails some months ago, I mentioned my idea to Michael, who fell in love with the concept.

To make a long story short, once he recovers from the spinal fusion surgery he had yesterday, Michael’s going to tackle my project. I guess that I will receive some sort of writing credit for it, since it was my idea, but it’s mostly going to be Michael’s work product. Michael has the connections to get someone famous–hopefully, a Hall of Famer–to write an introduction to the book for us, which will make it even better still. Here’s the working title, which Michael came up with the other day: USTINK: Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players. I like it.

I’m just thrilled that this idea I came up with 35 years ago is finally going to come to fruition. I mentioned it to Ted Savas yesterday, and he liked the idea a great deal, too.

So, stay tuned. We will see where this fun little side trip leads. Fear not–I don’t anticipate that this will serve as any major hindrance to my getting my various Civil War projects done.

Scridb filterI was sad to see that Brian Dirck has decided to pull the plug on his excellent Abraham Lincoln blog, but I understand the reasons. Blogging can be a time-consuming thing, and Brian felt that it was taking away from other things he has to do. I completely understand, and there are times when I feel the same way.

I will miss Brian’s blog. Always insightful, I looked forward to reading it every day. Good luck to you, Brian. You will be missed.

Scridb filterThese are sixteen photos from my trip this past weekend. This first batch are from the battlefield at Five Forks.

This photo was taken at the right end of the Union line at Five Forks, where the Union cavalry hit the Confederate line.

This photo shows the Confederate trenches extending back into the woods at the angle of the Confederate line, where part of it bent back to refuse the flank. It’s not easy to see them clearly, but they’re there. They’re on the left side of the photo, and snake back into the woods.

This is the monument to the Battle of Five Forks, which is located at the intersection where the five roads come together.

This is the position where Col. Willie Pegram’s guns were, and where Pegram received his mortal wound. Behind the gun is the old visitor center at Five Forks. It’s an old gas station and is obviously not a historic structure. On March 26, ground will be broken to build a new visitor center for Five Forks, and once it’s done, this thing will be torn down.

This is far end of the Confederate line at Five Forks, where Fitz Lee’s cavalry was routed. Look at those open fields, perfect for mounted operations.

I also stopped at the Sutherland’s Station battlefield on my way back toward Petersburg. I’d never seen it before. Sutherland’s Station was fought on April 2, 1865 and marks the final cutting of the Southside Railroad by the Union army. These are two historical interpretive markers there.

This is a monument to the Confederate forces who fought at Sutherland’s Station.

This is the small marker on the spot where Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill received his mortal wound. It’s near Pamplin Park, behind a subdivision. I don’t think many people visit the spot.

This is from Thursday afternoon, although we visited this spot on Saturday. Bobby Krick took me here. These earthworks represent a small surviving section of the outer ring of defenses of Richmond. These works were briefly occupied by Judson Kilpatrick on March 1, 1864 and by Phil Sheridan on May 12, 1864. Both ultimately decided that they could not carry the intermediate line of works.

This lovely home is called Rose Hill. It’s at Stevensburg, VA, and served as Judson Kilpatrick’s headquarters during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. We had a tour of the home. The fellow in the brown jacket is my old friend Horace Mewborn, who is pretty much THE authority on Mosby’s Rangers.

Our tour leader, Dr. Bruce Venter, THE authority on the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid, holding court on Friday.

This is a nifty little monument to a trooper of the 4th Virginia Cavalry named Pvt. James Pleasants, who captured 13 men and killed one after being roused by Dahlgren’s raiders as they passed through Goochland County on March 1, 1864.

This is the James River in Goochland County. Dahlgren tried to cross here (it’s usually fordable), but when Dahlgren’s column came through, the river was at freshet and could not be forded. Dahlgren tried again about three miles further downriver and failed a second time.

This was Benjamin Greene’s farm in the Westhampton section of Richmond. This spot marks the focus of the battle between Dahlgren’s men and the defense forces of Richmond that occurred late in the afternoon of March 1, 1864. We were there at about the same time as the battle, so we were able to get a real sense of what it was like as the fighting raged. The house then served as a hospital. We were permitted into this gorgeous old house, and it’s quite a place to see.

This is Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. Kilpatrick burned it during the raid, and Custer did so again during the May Richmond Raid. It was a popular spot.

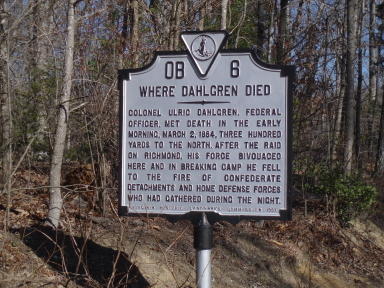

This is the Virginia historical marker at the site where Ulric Dahlgren was ambushed and killed. It’s pretty much self-explanatory, although it’s not entirely accurate. Dahlgren was killed between 10 and 11 at night on March 2, not in the early morning hours, and he was killed pretty much at the site of the marker, and not a couple of hundred yards away, as the marker indicates. Our visit to the ambush site pretty much marked our final stop of the tour.

I took a few more photos, but these ought to give you a taste of the trip. It was a very good but exhausting time. We covered nearly 375 miles in the bus, and saw an awful lot. We spent nearly two full days touring and seeing the sites. I’m glad that I went, as I came away from the tour wit a lot of different insights and perspectives on things that have subsequently made their way into the manuscript.

Scridb filterWe were up and on the bus at 8:00 again this morning. We headed up to Beaver Dam Station, a stop on the Virginia Central Railroad not far from the North Anna battlefield of May 1864. We heard about Kilpatrick’s demolition of the depot there, and then headed down into Richmond to address Kilpatrick’s attempt to push through the defenses of the Confederate capital. A small piece of the outer ring of defenses still exists at Brook Hill, which happens to be the spot where both Kilpatrick in March 1864 and Sheridan in May 1864 tried to push through. Bruce interpreted there, and then we headed in to where the intermediate line of defenses stood.

Kilpatrick, alone and unsupported, and with Bradley T. Johnson’s 1st Maryland Cavalry operating in his rear, for once, made the prudent decision and broke off instead of sending his mounted cavalrymen charging into the static defenses of Richmond. He then headed for Meadow Bridges, crossed the Chickahominy swamp there, and marched toward Atlee’s Station. There, a portion of Wade Hampton’s division, with Hampton in personal command, routed the 7th Michigan Cavalry and persuaded Kilpatrick to get out of Dodge. He fled toward Kent City Courthouse, where he met a relief column sent from Williamsburg by Ben Butler. Our last Kilpatrick stop was at Tunstall’s Station on the old James River Railroad, where Kilpatrick burned the station and was joined by the portion of Dahlgren’s command that broke through Johnson’s Confederates to rejoin the main body.

From there, it was on to the area of Hanovertown Ferry, where Dahlgren’s remnant of about 100 men crossed the Pamunkey, and then on into King and Queen County. We crossed the Mattaponi at Ayletts, just as Dahlgren did, and then proceeded on to the ambush site. After interpreting the ambush, Bruce and I laid out our respective theories as to who knew and approved what regarding the plan and the legitimacy of the Dahlgren Papers. Bruce believes Dahlgren cooked it all up on his own, while I believe it was cooked up by Kilpatrick and Stanton and that Dahlgren likely participated in the process.

That was the end of the tour, and we then headed the 30 miles back to Richmond. Along the way, Bruce gave some analysis of the raid and its results and consequences, and I spent most of the ride back hashing out some new thoughts/insights that I developed over the last two days as a consequence of both seeing the sites as well as having the benefit of having Bruce’s analysis and commentary. After saying our goodbyes, I headed straight back up to my hotel room and incorporated all of the new stuff into the manuscript. While I thought that the manuscript was good previously, I think that it’s even better now. I feel really good about it, and think it’s going to make for a really good conclusion chapter to my biography of Ulric Dahlgren.

I’m now sitting in my hotel room, hanging out. Pretty much everyone who attended the conference dispersed immediately after the conclusion, and I have a very early flight tomorrow. My flight home is at 7:30, and it’s nearly 20 miles to the airport. That means it’s up at 5:00 again tomorrow. I CANNOT wait until Skybus starts its second flight per day to Richmond, which will leave Columbus at 5:00 PM. No more of these ridiculously early mornings.

Tomorrow night, when I get home, I will post some photos from the weekend. For now, it’s time to just rest and try to get ready for what’s going to be another long and stressful week.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like