This is a profile of a forgotten cavalryman that I’ve wanted to do for some time. I owe Ranger John Hoptak a big debt of gratitude for passing along the missing material that I’ve long wanted but have been unable to obtain. Thanks, John.

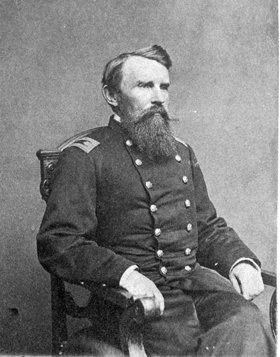

Forty-seven year-old Maj. Charles Jarvis Whiting of the 5th U.S. Cavalry led the Reserve Brigade. Whiting was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts on November 28, 1814 and was raised in Castine, Maine, and from the time of his childhood, his overarching ambition was to become a West Point cadet. When he received his appointment, he made the trip to West Point and was turned away for being too short. He spent the next year hanging from trees with a brick tied to each foot, hoping to stretch himself enough to meet the height requirement. He returned to the Academy the next year and was admitted. He graduated fourth in the Class of 1835.

Forty-seven year-old Maj. Charles Jarvis Whiting of the 5th U.S. Cavalry led the Reserve Brigade. Whiting was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts on November 28, 1814 and was raised in Castine, Maine, and from the time of his childhood, his overarching ambition was to become a West Point cadet. When he received his appointment, he made the trip to West Point and was turned away for being too short. He spent the next year hanging from trees with a brick tied to each foot, hoping to stretch himself enough to meet the height requirement. He returned to the Academy the next year and was admitted. He graduated fourth in the Class of 1835.

He was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery and served engineering duty during the Seminole War in Florida. He resigned his commission on May 31, 1836 to become a railroad surveyor in the Florida panhandle. In 1838, he served as the assistant engineer for the survey of the Mississippi River delta. He then settled in Maine, where he established, and served as headmaster of, the Military and Classical Academy in Ellsworth, which a promising young student named Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain attended. He married in June 1841, and had a daughter. His wife died in 1847, leaving Whiting a 33-year-old widower with an infant daughter, Anna Waterman Whiting. His wife’s family raised Anna, for the Army was no place for an infant.

After teaching for six years and with his wife dead, Whiting surveyed the boundary between the United States and Mexico that was established by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Whiting then settled in San Jose, California, where he farmed and surveyed. For the years 1850-1851, he served as Surveyor-General of California.

When the size of the Regular Army was increased in 1855, a new regiment of light cavalry was formed. On March 3, 1855, Whiting was commissioned a captain in the newly formed 2nd U.S. Cavalry (which was re-designated as the 5th U. S. Cavalry in 1861). He saw extensive action in the west, fighting against Comanche Indians on several occasions, and earning praise for his valor in combat. The New Englander was known as an ambitious martinet who was eager to advance his own career. The coming of Civil War gave him that opportunity.

In March 1861, at the height of the secession crisis, Whiting was stationed at Fort Inge in Texas. When Texas left the Union, he and other loyal officers were stranded there. Whiting and Capts. George Stoneman and James Oakes met to discuss how to escape. They pondered the possibility of trying to escape to the Jefferson Barracks via the Indian country. However, they had insufficient supplies and no transportation, so they abandoned the plan. Stoneman and Whiting eventually found their way back to Washington, D. C. on a steamboat. Whiting was assigned to teach new recruits basic cavalry tactics at the Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. He also took a brief furlough to return home to Maine to marry Phebe Whitney, the younger sister of his brother’s wife.

A veteran officer like Whiting was needed at the front, and he was immediately called to rejoin his regiment, which was assigned to the defenses of Washington and in Patterson’s Valley Campaign of 1861. During that campaign, he demonstrated a personality trait that cost him dearly two years later. “It is said when he was ordered, at Falling Waters, to proceed with a squadron in search of a militia regiment which had become detached from the army, that he never ceased during the entire movement, to express his opinion of militia in general and of the politicians who were responsible for the war,†duly recorded the historian of the 5th U. S. Cavalry.

Whiting then served in McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign of 1862. He led the 5th U.S. Cavalry in its ill-fated sabre charge against Confederate infantry at Gaines Mill in June 1862, and was captured when his horse was shot out from under him. An account of this charge reads: “Only the cavalry and a part of the artillery remained on this part of the field. A brigade of Texans, broken by their long advance, under the lead of the hardest fighter in all the Southern armies, come running on with wild yells, and they were a hundred yards from the guns. It was then that the cavalry commander ordered Capt. Charles J. Whiting, with his regiment to charge. No one had blundered; it was the supreme moment for cavalry, the opportunity that comes so seldom on the modern field of war, the test of discipline, hardihood and nerve. Right well was the task performed. The 220 troopers of the Fifth Cavalry struck Longstreet’s veterans squire in the face. Whiting, his horse killed under him, fell stunned at the foot of the Fourth Texas Infantry.â€

After spending a month in Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison, he was sent north to Washington under parole and then was exchanged for another captain and promoted to major. Whiting commanded the 5th U. S. Cavalry throughout the fall and winter of 1862-1863 and participated in the Maryland Campaign and also in the Battle of Fredericksburg, although the role of the cavalry was extremely limited in the great December battle. Whiting also led his regiment in the 1863 Stoneman Raid that occurred during the Chancellorsville Campaign.

Although he was one of the oldest serving officers in the Regular cavalry, Whiting assumed command of the Reserve Brigade in June 1863 when Buford took command of the 1st Division. His brigade consisted of the U.S. Army Regular cavalry units assigned to the Army of the Potomac, the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th U. S. Cavalry, and the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (also known as Rush’s Lancers). His tenure in brigade command was brief, lasting only a couple of weeks.

Whiting led the Reserve Brigade during the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. The major gave the 2nd U.S. Cavalry orders that conflicted with orders from Buford, and the Regulars failed to join in a charge to rescue the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which had charged all of the Confederate horse artillery near St. James Church, infuriating Buford. Shortly after Brandy Station, Whiting was relieved of his command and sent to the Draft Rendezvous at Fort Preble in Portland, Maine. Unexpectedly, while serving in Maine, Major Whiting was “dishonorably dismissed from the service on November 5, 1863 for disloyalty and for using contemptuous and disrespectful words against the President of the United States.â€

A letter found in Whiting’s pension file at the National Archives lends a great deal of insight into why he was cashiered. The letter states that Whiting’s hotel room in Portland faced the public square and had a balcony. “A mass meeting of Republicans was announced for a certain evening to take place, at which General [Benjamin F.] Butler was to speak. The local committee called upon the Major, as the story goes, and asked him if he had any objection to General Butler hopping through his room in order to address the gathering outside the balcony. The Major replied, ‘by no means,’ and peevishly added, permitted he could have time to ‘lock up his spoons.’ The Committee was incensed and informed General Butler and the Maj. was removed from the service.†Whiting returned to the family home in Castine to ponder his future.

After the end of the Civil War, the expanded Army had a real need for experienced officers to command troops on the western frontier. In May 1866, President Andrew Johnson reinstated Whiting to duty as Major of the 3rd Cavalry, with his records stating “the disability of holding a commission by reason of said dismissal was removed by the President of the United States.†Whiting assumed command of Fort Marcy in New Mexico. He then assumed command of Fort Union, New Mexico.

During July 1867, a party of Navajos at Bosque Redondo reservation, believed to have stolen livestock in their possession, fought back when troops attempted to recover the livestock. Six soldiers died in the exchange. Major Whiting led troopers of the 3rd Cavalry from Fort Union “to quell the present outbreak and prevent the occurrence of any future troubles with those Indians.†By the time Whiting arrived, the outbreak of violence had been quelled, and he and his troopers returned to Fort Union. Whiting later headed a board of officers that investigated the incident at Bosque Redondo, and he was appointed commander of Fort Sumner when the board determined that the former post commander had provoked the Indians.

In May 1869, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and transferred to the 6th Cavalry. He was assigned to command the Army post at Greenville, Texas, where his troopers were to keep the peace between feuding former Confederates and former Union soldiers.

In 1870, he took command of Fort Griffin in Abilene, Texas, which was responsible for protecting travelers from raiding Kiowas and Comanches. After five months there, he was transferred to the supernumerary list on December 15, 1870. On January 1, 1871, at the age of 56, he was honorably mustered out of the service. He packed his belongings and headed home to Castine. He and his wife lived out the rest of their lives there, supported by an Army pension. As he got older, the old injury to his back at Gaine’s Mill gave him more and more trouble and pain. After 20 years of peaceful retirement, Whiting died on New Year’s Day 1890 at the age of 75. He was buried in Castine.

Whiting spent nearly 30 years in the Regular Army, all in the mounted service. His service was honorable, and he was a good soldier who deserved a better fate than being cashiered from the Army. Here’s to Charles Jarvis Whiting, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Eric,

Another good bio, thank you. I haven’t found much showing that the regular cavalry units did a lot during the 1862 Maryland Campaign. Have you found any good primary/secondary sources detailing what they did during September 1862?

Larry

Nice to see you blogging again, Eric.

Eric,

These are great little bios of little known cavalrymen…have you thought of gathering them up and putting them together in a book? Or maybe putting them in a separate category archive for easy access (and collecting).

I’m rolling on the floor…. “lock up his spoons.”

Chuck, I hadn’t thought of that, but it’s a great idea. Thank you for suggesting it.

Craig, I had the same reaction. I did a spit take when I read that.

Kevin, thanks. I’m feeling better. I’m not 100% yet, but it is definitely better.

Larry, I haven’t, but I also haven’t really looked. You might consider asking Don Caughey, who has a blog that is in my blogroll. Don has done a tremendous amount of work on the 6th US Cavalry, and he can probably tell you.

Eric

Eric,

Thanks for another excellent post on a forgotten cavalryman. Glad to see you are posting again.

Chris

Eric,

Very nicely done, and thanks for the plug.

Don

Fine story of a soldier who deserves to be remembered.

I read about the charge at Gaines Mill of the 5th US Cavalry in Bruce Catton’s Illustrated Centennial History of the Civil War. That book had battle maps that were a combination of map and simplified sketches of troops and terrain. One of the last lines in the Gaines Mill story tells of a heroic charge by the 5th US to protect V Corps’ withdrawal. Although I was a first-class teen-age Civil War buff, I had never searched out a story of that charge.

Just happened to be reading the NY Times background on Crimea and Sebastopol, read again about the British cavalry at Balaclava, and thought of Gaines Mill…had I mis-remembered?

I can’t think of another mounted charge against infantry during the Civil War (aside from Farnsworth’s hopeless effort at Gettysburg).