Category:

Civil War books and authors

A few minutes ago, I got off the phone with Dan Hoisington, the head honcho at Edinborough Press. At the suggestion of two friends, Bill Christen and fellow blogger Jim Schmidt, I submitted the Dahlgren bio manuscript to Dan. After making some revisions suggested by Steve Sears, I resubmitted a couple of pieces of the book, and Dan just informed me that he has accepted it for publication.

That’s great news. My research indicates that Dan, who has a master’s degree in history, is extremely selective about what he takes. He only puts out about four books per year, but all are quality works by good authors, and I’m flattered to have my work considered as such, particularly since I know that there are a lot of aspects of this book that are guaranteed to trigger controversy. Dan also puts out an aesthetically pleasing book, so I know that the production values will be good, too.

Most importantly, Dan shares my view of how to market and sell books. Consequently, I feel very comfortable with having the book placed there and knowing that Dan will be selling it.

For those interested, it looks like the book will have a spring 2009 release date, since Dan’s plate for 2008 is already full, in part with Jim Schmidt’s first book, which is scheduled for release in the spring.

Thanks to all for the support you’ve shown this project, as I’ve wrestled my way through it.

Scridb filterI spent about four hours scanning illustrations for the retreat book today. When it was all said and done, there were about 75 images. I have a couple I’m waiting to get from JD, meaning that the final tally will be close to 80, which does not count the photos of the modern appearance of the sites along the driving tour routes. I don’t know if Ted will permit us to use all of them–there are 80 for the main text, close to 50 for the driving tours, and 16 maps–but I would rather give him too many and have him cull some out than not enough and have a deficient book.

I tried something new today. The computer that I had been using for the scanner has been in my office since I went back out on my own at the end of March. So, I was looking at disconnecting it and bringing it home, or coming up with a new solution. I checked and found a Mac OSX driver for the scanner, installed it on my Mac laptop, brought the scanner downstairs, and scanned all of the illustrations while I suffered through the misery of yet another horrible performance by the Philadelphia Eagles this afternoon. It literally took about four hours to get them all scanned (600 DPI, saved as TIFF files), but they’re done. I have to admit that I had been REALLY dreading this task, and am very happy indeed that it’s now over with.

Fortunately, I have a very large collection of images of my own that I’ve accumulated over the years. It makes the job of locating and identifying illustrations for my book projects much easier and also goes a long way toward expediting the process to the extent possible. Most of them have now been digitized, so I doubt I will have to go through another four hour marathon again any time soon. Which will be just fine by me. It’s a pain. But, it’s done, and that’s the important thing.

As I’ve said previously, this is going to be a BIG book, more than 500 pages plus all of the images and maps mentioned here. I can’t wait to see this one in print.

Scridb filterAs J. D. has noted, we’ve gotten some very good news on the publishing front the last two days. Yesterday, Ted Savas told us that less than 50 copies remain of the second printing of Plenty of Blame to Go Around and that he has ordered a third printing. This is the first time that one of my books has gone to a third printing, so this is virgin territory for me.

Today, we got the good news that the publication date for One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 has been pushed up from June to May of 2008. Ted also told us that the price will be $34.95, which is a really good price for a book that will be more than 500 pages long. Finally, Ted told us that the book clubs are extremely interested in the retreat book, which is also very exciting news.

All things considered, today was filled with nothing but good news for the financial prospects of my book projects.

Scridb filterStephen W. Sears was kind enough to agree to write a foreword to the Dahlgren biography for me. In addition to being a terrific writer in his own right, Steve’s done a lot of editing in his day, including serving as an editor of the late, lamented American Heritage magazine. Steve not only wrote an excellent foreword for the book, he also gave me some really good suggestions for making it a better book.

I had originally written the conclusion by presenting the range of possibilities for what Lincoln knew and when he knew it and then permitting the reader to draw his or her own conclusions about this critical issue. Steve suggested that I should instead take a position–tell the reader what I think is the truth, based on the evidence–while dealing with the other possibilities and by using the evidence to eliminate them. I did so. It went through several drafts of re-write, and Steve gave me excellent feedback on each of those drafts.

It’s finally done. It’s at the point where I think it’s finished, and where I think that the conclusions stated are well-supported by the evidence at hand.

I also added some good new material from the very useful volume of the notebooks of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman that just add good insight to the overall manuscript, some of which I have already mentioned here. The addition of this material has only further bolstered the quality of this book.

I submitted the revised pieces of the manuscript to Dan Hoisington, the publisher of Edinborough Press, who is currently considering the manuscript for publication.

Scridb filterOld friend Jim Morgan asked me to put up an announcement here that he will be speaking on his excellent book on the Battle of Ball’s Bluff before the New York Civil War Roundtable on December 12. I’ve included a link to Roundtable’s page that provides the necessary information for anyone who might be interested in attending. Jim’s written an excellent book on a small but extremely important early battle in the Eastern Theater.

Scridb filterWell, it never fails.

Some of you might recall that I had breathlessly announced that the retreat book was not only finished, but that it had been submitted to the publisher, Ted Savas.

Last night, my friend Scott Mingus spoke to the Central Ohio Civil War Roundtable, and brought me a copy of his new book, Human Interest Stories of the Gettysburg Campaign, Vol. 2. Sure enough, while thumbing through the book last night, I found six really nifty items that ought to be included in the retreat book, as they really add to the story. So, today, I had to call Ted Savas and get permission to add stuff (Ted has already complained that the thing is too long), which he readily gave. So, now I have to add material to the book.

Just when I thought it was done, I get pulled back in……

Scridb filterThe following review of my history of the Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry, also known as Rush’s Lancers was published on H-Civil War:

H-NET BOOK REVIEW

Published by H-CivWar@h-net.msu.edu (November 2007)

Eric J. Wittenberg. _Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War_. Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2007. xi + 316 pp. Maps, photographs, bibliography, index. $29.95 (cloth), ISBN 1594160325.

Reviewed for H-CivWar by A. James Fuller, Department of History, University of Indianapolis

A Cavalry Regiment’s Ride through the Civil War

Regimental histories afford the historian the opportunity to bring the past to life through the shared experience of men in military service. Using the intimate lens of the individual like a biographer while tracing the collective story of the unit and connecting it to context offers new

insights and perspectives on the issues and questions raised in works of broader scope. In _Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War_, attorney Eric J. Wittenberg argues that the regiment overcame initial obstacles and obsolete weaponry with superb training and brave fighting that earned it the reputation as one of the finest cavalry units of the war.

Wittenberg is the author of many other books about the Civil War cavalry, including several studies of the role of horse soldiers in the Gettysburg campaign _Protecting the Flanks: The Battles for Brinkerhoff’s Ridge and East Cavalry Field, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2-3, 1863 (2002), _Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions (1998), and a biography of Philip Sheridan _Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan_ (2005). In researching battles and campaigns, he repeatedly came back to the Sixth Pennsylvania and this added to an interest that had been kindled when he was a boy growing up in a town from which one of the regiment’s companies had come. His passion for the subject and his expertise on cavalry make Wittenberg the ideal writer for a regimental history.

The regiment initially organized as Lancers when they mustered in fall 1861, and the men trained hard in learning to use the long spears that had proven so formidable in past conflicts. Considered obsolete by the 1860s, the lance still enjoyed many supporters, including George B. McClellan, who had studied the weapon’s use in Europe and urged Colonel Richard Henry Rush to

adopt it for his new unit. The regiment’s limited use of the lance, complete with red pennons to flutter in the breeze, soon gave way to the carbine. Despite losing the distinctive arms that had given them their identity, the unit kept its name.

That name came to mean something in the Union Army. By the end of the war, the Sixth Pennsylvania had earned respect and become a tough, hard-fighting regiment. But it was not an easy road. Most of the officers hailed from the elite families of Philadelphia, the unit was commanded by the grandson of Dr. Benjamin Rush, while others pointed to famous ancestors who had led or fought in the American Revolution. At the same time, the rank and file of the regiment was made up of young men from the lower ranks of society, including many from Philadelphia’s working class. Class tensions threatened to cause real problems early on, but when Philadelphia newspapers published accounts about the few officers whose aristocratic ways grated on the enlisted men, the tensions eased. Nationalism combined with training and

the personality of fine officers to overcome the dangers of class conflict in the regiment.

The real test came, of course, on the battlefield. Time after time, the Lancers rode into combat. From minor skirmishes and reconnaissance missions to raids and actions on the flanks of major battles, even full-scale cavalry clashes, the Sixth Pennsylvania found itself in action. In between came the tedious monotony of camp life and the inevitable hardships caused by the

weather, the supply situation, and separation from home and family. Sometimes the enemy proved less dangerous than epidemics. As the months rolled into years, the Lancers developed into veterans and became a reliable unit upon whom the generals could count.

Wittenberg rightly places the regiment’s history within the story of the brigade and always reminds his readers of the broader context of the war. Mistakes in decision making at the highest rank are brought to awful reality at the company, squad, and even individual levels. Familiar battles like Gettysburg are seen from the perspective of the cavalry, a view that sheds

new light on the whole campaign. Instead of the usual recounting of the battle, the reader is taken to places on the flanks and rides along with the Sixth Pennsylvania as the Confederates retreat. The great cavalry battle at Brandy Station receives a well-deserved chapter as does Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign. Success followed failure, disappointment followed victory. The regiment’s participation in the successful Stoneman Raid was part of the campaign that led to General Joseph Hooker’s defeat at Chancellorsville. Gettysburg was followed by disappointing results during Robert E. Lee’s retreat. Embarrassments gave way to proud victories as the Union cavalry learned to hold its own against its counterpart, and then

began to defeat the Southern cavaliers.

Throughout the book, the reader becomes familiar with the individuals whose writings make up the author’s main sources. Some of the men died, others were transferred, others were promoted, many reenlisted, and other new faces joined up. Officers and enlisted men, surgeons and chaplains are all given a voice. Some of them had the famous names of elite families, some were related to famous commanders (George Meade Jr. is the obvious example), some were wealthy lawyers, some were poor farmers, and some came from the wrong side of town. But they served together and Wittenberg allows a broad cross section of them to speak about their experiences. They served under famous generals: McClellan, Meade, John Buford, Alfred Pleasanton, George Custer, Sheridan, and Ulysses Grant. They fought against famous generals: Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Thomas Jackson, to name three. Wittenberg’s final chapter, “Requiem,” provides the stories of what happened to many of the familiar faces and brings them together in reunion celebrations.

At times, Wittenberg displays the storyteller’s gift and the reader is drawn into the narrative. It is, after all, an action packed tale. But he sometimes includes so much detail that his prose slows to a plodding slog that reminds the reader of some of the Lancers’ miserable rides through

terrible weather. This makes the book less attractive for use in the classroom and will make it less appealing to general readers. But, it is a must read for those interested in the cavalry, buffs, readers in the Philadelphia area, and specialists in Civil War history. The book is well

researched, generally well written, and the author’s argument is persuasive. In the end, Wittenberg has provided a very capable regimental history that deserves a place on the shelf alongside other such studies.

I’m very pleased with this review. I think it’s very fair and accurately reflects the book.

Scridb filter The November issue of Civil War News contains a really outstanding review of my Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War. I’m not normally one to blow my own horn–I actually find it unseemly–but this review is so good that I wanted to share it. As book reviews go, it doesn’t get much better than this.

The November issue of Civil War News contains a really outstanding review of my Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War. I’m not normally one to blow my own horn–I actually find it unseemly–but this review is so good that I wanted to share it. As book reviews go, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War

By Eric J. Wittenberg

Illustrated, notes, index, appendix, 304 pp, 2007. Westholme Publishing LLC, 8 Harvey Ave., Yardley, PA, 19067, $29.95 plus shipping.

Reviewer: Chuck Romig

Chuck Romig graduated from Penn State University with a B.S. in secondary education and teaches history at Penns Valley High School in Spring Mills, Pa. He continues to read and research Civil War history.

Review:

Eric J. Wittenberg has produced a gem of a regimental in Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War. Probably every Civil War buff can name one or two favorite John Wayne films and I’d be willing to bet that in at least one of those films the Duke was in the cavalry.

Wittenberg, in this work, expertly reveals not only untold morsels about one of the Civil War’s famed cavalry units, but also the experience of a horse soldier in the war.

He begins the story with the formation of the regiment in Philadelphia, Pa., spearheaded by one Richard H. Rush, a descendant of Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia renown. Rush was a member of the West Point class of 1846 but failed to live up to the reputation for which that class was known.

After a hiatus from the military Rush had problems gaining a commission in 1861. He used his family’s name to eventually gain rank.

The 6th Pennsylvania initially mustered at Camp Meigs in the City of Brotherly Love where they actually trained with lances, a fad that Gen. George McClellan had advocated since his Crimean trip.

After the endless drilling common to any volunteer regiment of the Civil War, the 6th Pennsylvania was ordered to join the Army of the Potomac at Manassas. On their way to the Peninsula to take part in that debacle, they sat as peaceful spectators and viewed the battle of Hampton Roads where the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia dueled to a draw in mid-March 1862.

Wittenberg uses his subjects to tell their story with deftness and accuracy. Pulling from a slew of privates, officers and a chaplain, he allows the men of the 6th Pennsylvania and those who interacted with them to tell their tale posthumously.

This style picks up once the men are on the Peninsula and continues through the Maryland Campaign of 1862, Fredericksburg, Stoneman’s Raid and Chancellorsville, Brandy Station, Gettysburg, the transition of Grant to the East, and the 1864 Valley Campaign.

Wittenberg’s work is filled with points of human interest, as well as strategic and tactical analysis, which make this regimental a more exciting read than many others. But it is not just the human interest and military analysis that make this book a keeper. It’s the group of troopers that Wittenberg chose as subjects.

I’m sure that stories as good as the 6th Pennsylvania’s exist, but there are none better. Taste these tidbits to understand what I mean. Why was Stonewall Jackson late in arriving on the Peninsula from the Valley? The 6th Pennsylvania.

Which was the only unit to get a shot off at Stuart’s troopers in their first ride around the Army of the Potomac? The 6th Pennsylvania. Who led brave charges into the teeth of hell at Brandy Station and South Cavalry Field at Gettysburg? The 6th Pennsylvania.

Theirs is a story that needed to be told. Frankly, I’m shocked it took this long with all the Civil War literature published these days.

Wittenberg matches fantastic subjects with an appropriate style of drawing from firsthand accounts in Rush’s Lancers. I wish more photographs would have accompanied the text, however, Wittenberg may have used all that were available. This one’s a good one.

Thanks, Mr. Romig. I’m humbled by your kind words for what was very much a labor of love for me. You’re quite correct in that I had an extraordinary set of subjects to work with here, all of which made the historian’s job that much easier. The eloquence of these men extended from the regimental colonel on down to lowly sergeants, all of which made documenting their exploits simpler.

I’m not quite done with the Lancers yet. I have one more project yet to go…..

And, to answer your one very mild complaint, I used EVERY photograph of a member of the Lancers that I could find. If I had managed to find more, they would have made their way into the book. There was only one photo that I did not use, of the very last reunion of the regiment, as it was a scan of a photocopy of an old newspaper, and it just didn’t duplicate well enough to run. As it was, many of those photos appear in the book for the first time anywhere.

Scridb filterIn August, I posted about the better features of Google’s book search feature. J. D. and I both made very extensive use of Google’s site, as well as the Microsoft live book search site (a note about the Microsoft site–it will not work on the Mac. That, in and of itself, is reason enough for me not to want to use it at all).

There is a third organization digitizing books. The Internet Archive is also digitizing public domain books and making them available. The following article appeared in today’s issue of The New York Times, and explains why I prefer the Internet Archive project:

Libraries Shun Deals to Place Books on Web

By KATIE HAFNER

Published: October 22, 2007

Several major research libraries have rebuffed offers from Google and Microsoft to scan their books into computer databases, saying they are put off by restrictions these companies want to place on the new digital collections.

The research libraries, including a large consortium in the Boston area, are instead signing on with the Open Content Alliance, a nonprofit effort aimed at making their materials broadly available.

Libraries that agree to work with Google must agree to a set of terms, which include making the material unavailable to other commercial search services. Microsoft places a similar restriction on the books it converts to electronic form. The Open Content Alliance, by contrast, is making the material available to any search service.

Google pays to scan the books and does not directly profit from the resulting Web pages, although the books make its search engine more useful and more valuable. The libraries can have their books scanned again by another company or organization for dissemination more broadly.

It costs the Open Content Alliance as much as $30 to scan each book, a cost shared by the group’s members and benefactors, so there are obvious financial benefits to libraries of Google’s wide-ranging offer, started in 2004.

Many prominent libraries have accepted Google’s offer — including the New York Public Library and libraries at the University of Michigan, Harvard, Stanford and Oxford. Google expects to scan 15 million books from those collections over the next decade.

But the resistance from some libraries, like the Boston Public Library and the Smithsonian Institution, suggests that many in the academic and nonprofit world are intent on pursuing a vision of the Web as a global repository of knowledge that is free of business interests or restrictions.

Even though Google’s program could make millions of books available to hundreds of millions of Internet users for the first time, some libraries and researchers worry that if any one company comes to dominate the digital conversion of these works, it could exploit that dominance for commercial gain.

“There are two opposed pathways being mapped out,” said Paul Duguid, an adjunct professor at the School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley. “One is shaped by commercial concerns, the other by a commitment to openness, and which one will win is not clear.”

Last month, the Boston Library Consortium of 19 research and academic libraries in New England that includes the University of Connecticut and the University of Massachusetts, said it would work with the Open Content Alliance to begin digitizing the books among the libraries’ 34 million volumes whose copyright had expired.

“We understand the commercial value of what Google is doing, but we want to be able to distribute materials in a way where everyone benefits from it,” said Bernard A. Margolis, president of the Boston Public Library, which has in its collection roughly 3,700 volumes from the personal library of John Adams.

Mr. Margolis said his library had spoken with both Google and Microsoft, and had not shut the door entirely on the idea of working with them. And several libraries are working with both Google and the Open Content Alliance.

Adam Smith, project management director of Google Book Search, noted that the company’s deals with libraries were not exclusive. “We’re excited that the O.C.A. has signed more libraries, and we hope they sign many more,” Mr. Smith said.

“The powerful motivation is that we’re bringing more offline information online,” he said. “As a commercial company, we have the resources to do this, and we’re doing it in a way that benefits users, publishers, authors and libraries. And it benefits us because we provide an improved user experience, which then means users will come back to Google.”

The Library of Congress has a pilot program with Google to digitize some books. But in January, it announced a project with a more inclusive approach. With $2 million from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the library’s first mass digitization effort will make 136,000 books accessible to any search engine through the Open Content Alliance. The library declined to comment on its future digitization plans.

The Open Content Alliance is the brainchild of Brewster Kahle, the founder and director of the Internet Archive, which was created in 1996 with the aim of preserving copies of Web sites and other material. The group includes more than 80 libraries and research institutions, including the Smithsonian Institution.

Although Google is making public-domain books readily available to individuals who wish to download them, Mr. Kahle and others worry about the possible implications of having one company store and distribute so much public-domain content.

“Scanning the great libraries is a wonderful idea, but if only one corporation controls access to this digital collection, we’ll have handed too much control to a private entity,” Mr. Kahle said.

The Open Content Alliance, he said, “is fundamentally different, coming from a community project to build joint collections that can be used by everyone in different ways.”

Mr. Kahle’s group focuses on out-of-copyright books, mostly those published in 1922 or earlier. Google scans copyrighted works as well, but it does not allow users to read the full text of those books online, and it allows publishers to opt out of the program.

Microsoft joined the Open Content Alliance at its start in 2005, as did Yahoo, which also has a book search project. Google also spoke with Mr. Kahle about joining the group, but they did not reach an agreement.

A year after joining, Microsoft added a restriction that prohibits a book it has digitized from being included in commercial search engines other than Microsoft’s.

“Unlike Google, there are no restrictions on the distribution of these copies for academic purposes across institutions,” said Jay Girotto, group program manager for Live Book Search from Microsoft. Institutions working with Microsoft, he said, include the University of California and the New York Public Library.

Some in the research field view the issue as a matter of principle.

Doron Weber, a program director at the Sloan Foundation, which has made several grants to libraries for digital conversion of books, said that several institutions approached by Google have spoken to his organization about their reservations. “Many are hedging their bets,” he said, “taking Google money for now while realizing this is, at best, a short-term bridge to a truly open universal library of the future.”

The University of Michigan, a Google partner since 2004, does not seem to share this view. “We have not felt particularly restricted by our agreement with Google,” said Jack Bernard, a lawyer at the university.

The University of California, which started scanning books with the Open Content Alliance, Microsoft and Yahoo in 2005, has added Google. Robin Chandler, director of data acquisitions at the University of California’s digital library project, said working with everyone helps increase the volume of the scanning.

Some have found Google to be inflexible in its terms. Tom Garnett, director of the Biodiversity Heritage Library, a group of 10 prominent natural history and botanical libraries that have agreed to digitize their collections, said he had had discussions with various people at both Google and Microsoft.

“Google had a very restrictive agreement, and in all our discussions they were unwilling to yield,” he said. Among the terms was a requirement that libraries put their own technology in place to block commercial search services other than Google, he said.

Libraries that sign with the Open Content Alliance are obligated to pay the cost of scanning the books. Several have received grants from organizations like the Sloan Foundation.

The Boston Library Consortium’s project is self-funded, with $845,000 for the next two years. The consortium pays 10 cents a page to the Internet Archive, which has installed 10 scanners at the Boston Public Library. Other members include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Brown University.

The scans are stored at the Internet Archive in San Francisco and are available through its Web site. Search companies including Google are free to point users to the material.

On Wednesday the Internet Archive announced, together with the Boston Public Library and the library of the Marine Biological Laboratory and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, that it would start scanning out-of-print but in-copyright works to be distributed through a digital interlibrary loan system.

The Internet Archive Project’s system is far superior to that of either Google or Microsoft because it’s the only truly open one available to the world. And it’s why I prefer to use its resources whenever possible.

Scridb filter

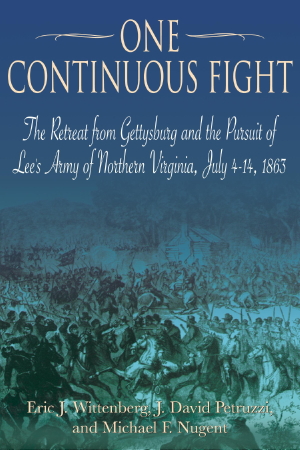

Here is the cover art for our book on the retreat from Gettysburg. The scene portrayed in the vintage woodcut is the July 8, 1863 Battle of Boonsboro. The cover art was done by the same graphic designer that did the cover art for the Stuart’s Ride book. The idea was to make the dust jacket for the retreat book be consistent with the Stuart’s Ride book, a la Gordon Rhea’s books on the Overland Campaign. It only makes me more eager to see the final product when the book is published.

There will be 16 maps, and something like 50 illustrations. Given the word count, Ted Savas tells me that we’re looking at a book in the range of 550 pages in length. That will be my longest book, by a long shot. Both of the driving tours include complete GPS coordinates, meaning that it will be VERY difficult for anyone following them to get lost.

There already seems to be some buzz building about this book. It’s a shame we have to wait for next June for it to come out…..

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like