Category:

Confederate Cavalry

I’ve decided to profile a couple of my favorite forgotten Confederate cavalrymen this week. Both ended the war as colonels, but both temporarily commanded brigades at times. Today’s profile is of Col. J. Fred Waring of the Jeff Davis Legion Cavalry, long a favorite of mine for the excellent diary of the last fourteen months of the war that he left behind. Thanks to old friend Paul F. Mullen for visiting the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah to get a couple of items on Waring for me. Finding biographical material on Waring is a challenge–he died young during a massive epidemic, so there is no obituary, and not much detail on his life has ever surfaced. What follows is the most detailed biography of him ever assembled or possible given the information that is presently available.

I’ve decided to profile a couple of my favorite forgotten Confederate cavalrymen this week. Both ended the war as colonels, but both temporarily commanded brigades at times. Today’s profile is of Col. J. Fred Waring of the Jeff Davis Legion Cavalry, long a favorite of mine for the excellent diary of the last fourteen months of the war that he left behind. Thanks to old friend Paul F. Mullen for visiting the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah to get a couple of items on Waring for me. Finding biographical material on Waring is a challenge–he died young during a massive epidemic, so there is no obituary, and not much detail on his life has ever surfaced. What follows is the most detailed biography of him ever assembled or possible given the information that is presently available.

Joseph Frederick Waring was born in Savannah, Georgia on February 13, 1832. He was the son of William R. Waring, M.D. and Ann (Johnston) Waring. He had a brother named James J. Waring. Young Fred enrolled in Yale University, graduating in the class of 1952. He studied law in Philadelphia for a year and a half after graduation and then spent a year traveling around Europe. When he returned to Georgia, he became a successful planter, and also served as a city alderman in Savannah. He was married to Louise (Early) Waring.

He served in an elite militia unit from Savannah called the Georgia Hussars. Organized in 1749, the Georgia Hussars represented Savannah in all wars from colonial times through 1994. Waring became captain of Co. F of the Hussars. He took his company to Virginia a few weeks later, reporting for duty in Richmond upon arrival. Co. F was originally assigned to become part of the 6th Virginia Cavalry when they arrived in Richmond, but this did not last long. Captain Waring was wounded in the face on December 4, 1861 while leading a nighttime raid to try to capture Federal pickets near Annandale. He received “a ugly gash of an inch or an inch and one half to his right cheek from a buckshot. His head grazed by another. The skin taken off the knuckles of his right hand, twelve holes through the cape of his overcoat.â€

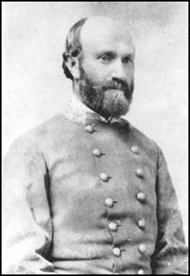

Three days later, Waring’s company of Georgia Hussars was assigned to become Company F of the Jeff Davis Legion, which was also called “The Little Jeff.†The Jeff Davis Legion was a hodgepodge—its companies included men from Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Waring was promoted to major early in 1862, and then, after participating in the Peninsula and Maryland Campaigns, was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the Jeff Davis Legion Cavalry on December 2, 1862. Waring became the regimental commander that December when Col. William F. Martin, the original commander of the Legion, was promoted to brigadier general and was transferred to the Western Theater. Waring commanded the Little Jeff for the rest of the war.

His unit served in Hampton’s Brigade, under the command of Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton, a gifted South Carolinian who eventually became the highest-ranking officer in the entire Confederate mounted arm. Waring ably led his unit through all of the major cavalry battles of the Eastern Theater, including Brandy Station, Gettysburg (where he was wounded for the second time), and Trevilian Station. In July 1864, he was promoted to colonel of the Legion, and that fall, he temporarily commanded Brig. Gen. Pierce M. B. Young’s brigade (which included the Little Jeff). Waring was a “brave and gallant†officer, but was unpopular with his command. Some of his men remembered him as “the type of a perfect knight, he was as tender of the rights of others as he was jealous of his own spotless honor,†and recalled him as “a leader of rare merit.â€

When Hampton was promoted to lieutenant general and sent to South Carolina in February 1865, his division, including the Jeff Davis Legion, went with him. Waring served through Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign, including the March 10, 1865 Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads, and surrendered at Bennett Place with the rest of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s command six weeks later.

The war over, Waring returned to Savannah, where he took a job as forwarding agent for the Georgia Central Railway Co. He also became the commanding officer of the Georgia Hussars, a position that he held until his death in 1876. “In peace firm and upright, just and generous, prompt and untiring, he achieved success and deserved it,†recalled a friend.

He returned to his post from a northern vacation just as a yellow fever epidemic reached its height. His job duties required him to be in the City of Savannah, and the disease struck him on September 30. He died of yellow fever at Whitesville, Georgia on October 4, 1876. He was only 44 years old when he died.

The men of the Georgia Hussars eulogized their fallen leader. “He was the pride of our Troop. Upon him centered our hopes, our love, our trust. The record of his life is our precious inheritance,†they declared. “In the prime of manhood, in the full maturity of every excellence, with the apparent promise of years of usefulness, he has been taken. But he has not lived in vain if his life leads us to aim at his high standard. He has not died too young, whose name is already famous.

J. Fred Waring was buried in Savannah’s Laurel Grove Cemetery.

Scridb filterAn active duty Army officer named Doug Davids left an interesting comment on my very early post on Tom Carhart’s crappy book. The comment left was good enough that I decided to pull it forward and feature in an actual blog post. Here’s the comment that Doug left earlier today:

Eric,

Sorry for the late reply. I’m at a busy time. Also, I’ll heed the warning on the language. I forget that civilians are not used to the sometimes overly blunt and colorful language we use in the military. I’ll tone it down. BTW: I appreciate you having a web site that opens up dialogue such as this discussion. I think it makes for great debate of an obviously very controversial topic.I must say I’m first very interested in who at the time said that Stuart was on the flank? That is a mystery to me, and I’d like to see how he stated it and in what context. Was it the report of Stuart’s aide…McClellan?

If I were to develop a MCOO (Modified Combined Obstacle Overlay) and a mobility overlay, Stuart would not end up on a flank, but clearly behind my lines. First, I recommend to try not to think of a units location based on latitude/longitude (as I know he is pretty much straight east of Ewell), but think of “effects†(a term we commonly use in our current combat zones). If Stuart’s intent was to somehow have an effect on the flank, he is much too far east to be doing a screening operation (i.e. on the defense), and if he is on the offense to effect the flank, he is pretty far away. I even had one of my armor NCOs state that if Stuart was trying to affect the Meade’s flank, he appears to be lost. I’ll talk McClellan’s comments later on.

If I were to make the overlays mentioned above, I would probably draw my lines to show anything that could possibly have an effect on my rear as anything east of Rock Creek and White Run Creek (I’m looking at a map which shows the battlefield din 1863), as I have Union cavalry screening just northwest of the White Creek area. On a modern map, Highway 15 is well behind my lines, and Stuart is well east of that. If I were the Operations Officer of an army, and I told my commander that Stuart was not in my rear, but on the flank, and he then saw Stuart’s position, I’d be on a quick airplane home with a recommendation on my officer evaluation report saying “do not promote†(as a minimum). From that position, Stuart is not in a good position to roll my flank, but he can have a devastating effect on my rear operations, regardless of his being about a mile or two north of my exact center rear. His position would be frightful in regards to what he could do to my rear area. If Carhart’s map is correct, all Stuart needs to do is take the Bonaughton and Baltimore roads, and my army will be experiencing a very significant emotional event in the worst way in a very short time. Stuart would not be in a good position to role my flank because he would run into the cavalry screening my flank. But he is in a great position to wreak havoc on my rear.

I doubt the theory some have used that Stuart was going to just harass the lines of communication (LOCs). Attacking LOCs can have varying effects depending on how far to my rear they are attacked. However, there is nothing Stuart can do to my LOCs which could affect my ability to hold off Picket in an attack which is about to take place. Also, rear areas in armies during those days were not like rear armies of today which practically have cities of headquarters and logistics behind them. Meade was up near the front lines, and any weapons and munitions which would be used in the attack were either near the line, or too late in coming to have an effect on the battle. Had Stuart attacked any logistical wagons along the road 12-24 hours earlier, it might have had an impact. But Lee was already out numbered in the battle. Therefore, the principle of war “Mass†and “Economy of Force†were of utmost importance to Lee, just as they had been in all Lee’s previously battles. He could not attack the full Union line, he had too few forces, but he had to use “economy of force†and concentrate his “mass†at the key location (something he was remarkably effective at during the 7 Days Battle). If Lee was sending the large groups of troops away from the battlefield to attack LOCs, I would need to take Lee of the list of great tacticians, and put him down with the three Bs (Burnside, Butler, and Banks). Napoleon’s Les Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrieres (or “Strategic Envelopment†as David Chandler translates it) had been an effective technique Lee had employed earlier, and with Stuart’s previously knowledge of the enemy rear area from his earlier venture, using the Les Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrieres was a very good idea on Lee’s part.

As far as an historical sense, I do know that Stuart’s aide, H.B. McClellan stated that “At about noon Stuart, with Jenkins’ and Chambliss’ brigades, moved out on the York turnpike, to take position on the left of the Confederate line of battle.†It’s an interesting comment and I wonder if that is the one you are refereeing to. The route does take Stuart to the Northeast, and then his move south obviously puts him in geographically east of Ewell, but I would never call Stuart on the “Line of battleâ€. In 1863 warfare, Stuart would need to be almost touching to be on the “line of battle.†In modern warfare I could see the term used, but not in 1863. If that was truly Stuart’s intent to be on the line of battle, then I think my armor NCO is correct in stating that Stuart “was lost.†However, I cannot image Stuart moving several miles up the York Road and thinking he was still on the “line of battle.†He is anything but. If that is McClellan’s true intent, he is either mistaken, or intentionally trying to cover things up. I don’t know a military mind today who would call Stuart “on the line of battle†when he met the Union cavalry.

McClellan also states that “Stuart’s object was to gain position where he would protect the left of Ewell’s corps, and would also be able to observe the enemy’s rear and attack it in case the Confederate assault on the Federal lines were successful.†“Protect the left of Ewell’s corps? !!!!“ This leaves me seriously in question of McClellan’s motives about writing this. A proper screening operation to protect Ewell’s flank and rear would have been to have positioned his troops generally along creek that goes from behinds Ewell’s lines (Stuart would have needed to connect to the east flank of Ewell, of course), and generally hold the line along that creek as it goes between Benner’s and Wolf’s Hill (I don’t see a name on the creek on the old 1863 map I am looking at). Whether Stuart screened along the creek or on the hill would depend on the terrain on the ground, but based on a map recon, I’d initially look at putting my cavalry along the northwest side of the creek, and position my artillery on Benner’s Hill (vegetation and visibility from Benner’s Hill would obviously effect my decision). I would then ensure that I had proper surveillance on both Hanover and York Pike roads.

But as it was, Ewell’s rear and flank were very much vulnerable to Gregg’s cavalry had Meade and the Army of the Potomac had any sense of offensive operations in mind. Ewell’s rear was so exposed that I’m surprise that Gregg didn’t request an attack. There was nothing stopping it. Again, if McClellan really calls Stuarts position near the Low Dutch Road as ‘protecting Ewell’s corps,’ I need to put both Stuart and Lee on the list of the three Bs. Most offensive-minded commanders would dream of such an enemy “flank protection†position. I have great difficulty believing that McClellan really thought he could be taken seriously by professional military officers in saying that the two mile gap between Stuart and Ewell was ‘protecting Ewell.’ The position of the cavalry battle field leaves both the Hanover and York Pike roads complete exposed. Stuart is not protecting the Confederate rear!!! Perhaps had McClellan known the battle would be studied so much, he might have found a different excuse. Not to be rude, but I question McClellan’s sanity with the comment. No military mind would ever call Stuart’s position “flank protection“ or “rear protection†of any confederate force that day.

The final point would come to “hearsay, I suppose. As Fitzhugh Lee wrote: “The position held by my cavalry at Gettysburg on the morning of the 3d was held by them at dark. They never left it except to go to the front in a charge. Such a condition of things could not have existed had other portions of the line been abandoned.â€

That seems to indicate that Stuart stayed on the defensive the whole time. Yet, as Carhart quotes William Brooke-Rawle of the 3rd Penn, “In close columns of squadrons, advancing as if in review, with sabers drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight, the spectacle called forth a murmur of admiration. It was, indeed, a memorable one.†There does seem to be room for Carhart’s comments that 4,000 confederates were on the move. Being so close to Meade’s rear, it would be a mystery of all times if Stuart had not made an attempt to strike Meade in the rear.

I think to sum it up I really have to question McClellan’s motives in why he said Stuart was in a position to protect Ewell. If the man were here today and told me that, I’d have no trouble telling him he were either completely ignorant or stupid, or a very bad liar. Stuart was in NO position to protect any part of the Confederate army, but he is in a dandy position to attack Meade’s rear!

V/R Doug

I appreciate the input and the dialogue.

The answer, of course, comes at least in part from Stuart’s own report. Here’s what Stuart said in his own report:

During this day’s operations, I held such a position as not only to render Ewell’s left entirely secure, where the firing of my command, mistaken for that of the enemy, caused some apprehension, but commanded a view of the routes leading to the enemy’s rear. Had the enemy’s main body been dislodged, as was confidently hoped and expected, I was in precisely the right position to discover it and improve the opportunity. I watched keenly and anxiously the indications in his rear for that purpose, while in the attack which I intended (which was forestalled by our troops being exposed to view), his cavalry would have separated from the main body, and gave promise of solid results and advantages.

Stuart does not say anything about having been ordered to launch an attack that was coordinated with the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge. Rather, it’s quite clear that what he had in mind was to exploit an opportunity if it presented itself. I have no reason to believe that Stuart’s intentions were anything but what precisely what he said in his report.

His report is entirely consistent with Robert E. Lee’s words. Here’s what Lee said in his report:

The ranks of the cavalry were much reduced by its long and arduous march, repeated conflicts, and insufficient supplies of food and forage, but the day after its arrival at Gettysburg, it engaged the enemy’s cavalry with unabated spirit, and effectually protected our left.

NOWHERE does Lee say anything about Stuart’s operations having been intended to be coordinated with the infantry assault. His report states clearly that Stuart’s operations “effectually protected our left.” In other words, Stuart operated on the flank, just as he reported that his mission was intended to be.

It seems to me that if the intention had been to coordinate something with the infantry assault, surely either Lee or Stuart, or more likely both, would have said something about it. Neither did. I think that we’re entitled to accept their reports at their face value. While I very much appreciate Doug’s analysis, the historical evidence simply doesn’t support the conclusion.

Doug, thanks for writing, and please feel free to continue the discussion in the comments to this post.

Scridb filterTime for another in my infrequent series of forgotten cavalrymen. Today, we have a guest biographer, Sheridan “Butch” Barringer, who is a cousin of our featured horseman, Brig. Gen. Rufus Barringer, the final commander of the North Carolina Cavalry Brigade. Butch was named for his father who, ironically, was named for Phil Sheridan, who captured General Barringer at Namozine Church during the retreat to Appomattox in April 1865.

Here’s Butch’s profile of his famous ancestor:

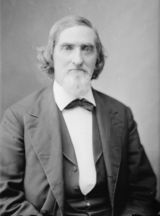

Rufus Barringer, a third generation American of Southern aristocracy, was born on December 2, 1821, in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. His father was Paul Barringer, an influential citizen of the county and officer in the militia during the War of 1812. His mother was Elizabeth Brandon, daughter of Matthew Brandon, a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Rufus was the tenth of eleven children, many of whom went on to achieve prominence.

Rufus was graduated from the University of North Carolina (UNC) in 1842, where he was active in the Dialectic Society (Debating Club), and was one of the leaders opposing the establishment of fraternities, which he considered too secretive and because he detested the severe hazing. After graduation, he returned to Concord and read law with his brother, Moreau. In June 1843, he obtained his license to practice law.

Rufus served in the North Carolina House of Delegates in 1848-49 and in the State Senate in 1850. Barringer supported progressive measures during his terms in the North Carolina Legislature, including establishment of a railroad system to serve the western part of the state,”free suffrage,” and judicial reforms.

Just prior to and during his legislative days, he purportedly had an affair with Roxanna Coleman, a mulatto slave of a neighbor in Concord. He fathered two illegitimate sons, Thomas Clay Coleman and Warren Clay Coleman. Warren Coleman is best known for establishing a black owned and operated textile mill in Concord. He became one of the wealthiest black men in the South before he died in 1904.

Also, during this period, Rufus was involved in a bitter political dispute with a prominent political figure of the time, Greene W. Caldwell. During the escalating clash with Caldwell, a duel was narrowly averted, but Caldwell attacked Barringer in the streets of Charlotte. The younger and stronger Barringer grappled with Caldwell and forced his attacker’s arm down so that three shots went through Barringer’s coat while one bullet hit him in the fleshy part of the calf of a leg. Both men were arrested and were fined, ending the dangerous affair.

After one term as a senator, Rufus tired of the legislative morass and returned to Concord, where he became heavily involved in taking care of Moreau’s practice after Moreau was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives, where, Moreau shared a desk with and became friends with another Congressman, Abraham Lincoln. This relationship proved fateful to Rufus Barringer.

In 1854 Rufus, a faithful Presbyterian, became engaged to Eugenia Morrison, fifth child of Robert Hall Morrison and Mary Graham Morrison of Lincoln County. Mr. Morrison was a prominent Presbyterian minister and the founder of Davison College. Rufus and Eugenia were married in May of 1854 and had two children, Anna Barringer and Paul Brandon Barringer. In 1874 Anna Barringer, 17, died of typhoid fever. Paul became a doctor, chairman of the faculty at the University of Virginia, and sixth President of Virginia Tech. Two other Morrison sisters married soon-to-be Confederate generals. Isabella Morrison married Daniel Harvey Hill, and Anna Morrison married Thomas J. Jackson. Thus, Rufus, Jackson, and Hill were brothers-in-law. In 1858, Eugenia died of typhoid fever. Three years later, Rufus married Rosalie A. Chunn, who died of tuberculosis in 1864, after having one child, Rufus Chunn Barringer. In 1870, he married Margaret Taylor Long, and they had one son, Osmond Long Barringer.

Barringer was a Unionist at heart and opposed secession until the failed Peace Conference of February 1861 (Moreau was a North Carolina representative to the conference). Rufus then encouraged secession and preparing the state for the war that he saw as inevitable. He raised a company of cavalry in Concord, and was elected its captain. Barringer’s Company “F” became part of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry Regiment (Ninth State Troops), commanded by Colonel Robert Ransom.

Barringer, Hill, and Jackson had cordial relations before and during the war, but Barringer and Hill became estranged over Reconstruction politics after the war. In July 1862, Jackson summoned Barringer to his headquarters to discuss Jackson’s proposed controversial “Black Flag” policy as a response to Federal commander John Pope’s threats toward Virginia civilians. Jackson never received approval for his “no quarter” war plan, and Pope’s offensive soon made the subject moot.

At the battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, Captain Barringer, acting as major that day, was seriously wounded while placing some of his troopers in position as sharpshooters to protect the Confederate artillery of Robert F. Beckham. Barringer was shot off his horse, being hit through the right cheek by a Federal sharpshooter. The bullet exited his mouth, causing serious injury that kept him out of service for five months. He was promoted to major on August 26, 1863, and returned to service at the time of the Bristoe Campaign in mid-October. Here, he rallied his troopers at Auburn and led a mounted charge at Buckland. He was promoted to Lt. Colonel on October 17.

During the 1864 spring campaign, North Carolina Brigade commander James B. Gordon was mortally wounded on May 12 at Brook Church, five miles north of Richmond during Sheridan’s attack on Richmond to draw out and fight JEB Stuart. After the death of Gordon and the wounding of Colonel William H. Cheek on May 11, Lt. Colonel Barringer took over temporary command of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry Regiment. Three senior colonels stood ahead of Barringer to be promoted to brigadier general to command the North Carolina Brigade, but Barringer, favored by Gordon and recognized as a sound organizer and disciplinarian, was promoted over the colonels, bypassing the rank of colonel to command the brigade as a brigadier general.

General Barringer performed well during the 1864 campaigns, leading Rooney Lee’s Division due to Lee’s illness during the victorious battle of 2nd Reams’s Station on August 25, 1864. He led his brigade in other fights, including Davis’s Farm, the Wilson-Kautz Raid, and Wade Hampton’s “Beef-Steak” Raid.

At the opening of the 1865 campaign, General Barringer was conspicuous in the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House (Chamberlain’s Bed), Five Forks, and Namozine Church, where a band of Maj. Henry Young’s scouts, disguised as Confederates, captured him on April 3, 1865. He was taken to Phil Sheridan’s headquarters, where he breakfasted with the Union general. He was then sent to Petersburg and to City Point, and was at City Point on April 5, when President Lincoln visited. Barringer was the first Confederate general officer captured and brought to City Point, and Lincoln, hearing the name Barringer of North Carolina, asked that Barringer be brought to see him. Lincoln thought that the prisoner might be his old friend Moreau Barringer. The two men had a congenial conversation for a period of time. Lincoln gave Barringer a note of introduction to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, since Barringer was being sent to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington. Barringer then met with Stanton for short periods over several days. Stanton had to clear out the prison because many prisoners were being received and gave Barringer the choice of prisons to be sent to. The hapless Barringer chose Fort Delaware—the worst choice he could have made.

Barringer arrived at Fort Delaware and stayed there until July 25, 1865, even though he made numerous attempts to obtain a release. After his release, he went to Washington in an unsuccessful attempt to obtain his pardon, and then went home to Concord, North Carolina. Moving to Charlotte during the post war period, he became a “Radical” Republican and strongly supported Reconstruction and was condemned by the Democratic press as a “traitor to his state.” D. H. Hill termed Barringer, and other Republicans, especially James Longstreet, as “lepers in their own community.” Hill, an elder of the First Presbyterian Church of Charlotte, refused to serve Barringer the sacraments at communion, declaring that “Republicans were not fit to sit at the Lord’s Table.” Barringer, angered at such treatment, transferred his membership to the Second Presbyterian Church and became an elder. A fearless politician, Barringer boldly stood his ground and supported black suffrage and other progressive measures to better the lives of the common people.

In 1880, Rufus Barringer was the Republican candidate for Lt. Governor, and was defeated along with Republican gubernatorial candidate Ralph Buxton, even though they nearly carried Barringer’s Democratic district. During the 1888 national election, Barringer switched parties, supporting Democrat Grover Cleveland for president. Suddenly, he was a hero to the Democratic Press, and remained so for the rest of his life. He died of stomach cancer on February 3, 1895 and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Charlotte.

Thanks to Butch for the excellent contribution. Here’s to Rufus Barringer, forgotten Tar Heel cavalryman.

Scridb filterSince I’ve profiled a Union cavalry officer who was an alumnus of Dickinson College, fairness requires that I similarly profile a Confederate Dickinsonian.

Richard Lee Turberville Beale was born into a prominent Virginia family on May 22, 1819. Young Beale attended private schools in Westmoreland County, Northumberland Academy and Rappahannock Academy, Virginia. He enrolled in Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with the class of 1838 and was elected to the Union Philosophical Society. He later left Dickinson and then completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Virginia in 1837. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and opened a private a practice in his hometown of Hague.

Richard Lee Turberville Beale was born into a prominent Virginia family on May 22, 1819. Young Beale attended private schools in Westmoreland County, Northumberland Academy and Rappahannock Academy, Virginia. He enrolled in Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with the class of 1838 and was elected to the Union Philosophical Society. He later left Dickinson and then completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Virginia in 1837. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and opened a private a practice in his hometown of Hague.

Beale also entered politics. Active in the Democratic Party, he was elected to a serve in the Thirtieth United States Congress in 1847, was a member of the 1851 Virginia constitutional convention, and served as a Virginia state senator from 1858 to 1860. He was married to the former Lucy Brown, and had several children.

Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War, in May, 1861, he was commissioned a lieutenant of cavalry in Lee’s Light Horse, a provisional unit which was later organized into the 9th Varginia Cavalry, known as “Lee’s Legion.” The unit was named for its first colonel, William H.F. Lee, the second son of Robert E. Lee. He was soon promoted captain and then major, was put in command at Camp Lee, near Hague, on the lower Potomac, where his intelligence and excellent judgment were of much value. Beale had achieved the rank of major by October 1861.

In 1862, he was named lieutenant colonel of the 9th Virginia. When Lee was promoted to colonel in the fall of 1862, Beale was promoted to colonel of the 9th Virginia. In December, 1862, he attracted attention and much favorable comment by a bold expedition into Rappahannock county, in which the Federal garrison at Leeds was captured, without loss. He served in all the cavalry battles of the Army of Northern Virginia including Fredericksburg. On April 16, 1863, he won the praise of J. E. B. Stuart for his heroic service in meeting and repelling the threatened raid of Stoneman’s cavalry division, and during the renewed movement by Stoneman at the close of the month, he was for a week in almost constant fighting, his regiment everywhere behaving valorously and capturing many prisoners. At the Battle of Brandy Station, he led the 9th in a brilliant charge in which Gen. W. H. F. Lee was wounded and Col. Solomon Williams of the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry was killed.

Beale also played a significant role in Jeb Stuart’s ride during the Gettysburg Campaign. Late in life, when he wrote a history of the 9th Virginia Cavalry, he recalled with affection seeing his alma mater during J.E.B. Stuart’s brief occupation of Carlisle on July 1-2, 1863. His son George W. Beale served as an officer in the regiment.

He was wounded in a skirmish at Culpeper Court House on September 13, 1863 and spent three months on convalescent leave. He returned to duty in January 1864, assuming command of his brigade and was eventually named a brigadier general. In March, 1864, having been stationed on the Northern Neck, he made a forced march to intercept Col. Ulric Dahlgren and his Union raiders, and a detachment of his regiment under First Lieut. James Pollard, Company H, successfully ambushed the Federals. Pollard, aided by other detachments, captured about 175 men and killed Dahlgren. The papers found upon Dahlgren’s person, revealing a design to burn Richmond and kill President Davis and cabinet, were forwarded by Colonel Beale, through Fitz Lee, to the government. A correspondence with the Federal authorities followed, in which they disavowed all knowledge of such a design. He participated in command of his regiment in the campaign from the Rapidan to the James, was distinguished in the fighting at Stony Creek, and toward Reams’ Station, in July, capturing two Federal standards; and in August, upon the death of Gen. John R. Chambliss, Jr., was given command of Chambliss’s brigade. February 6, 1865, he was promoted to brigadier general, and in this rank he served during the remainder of the struggle. Official confirmation of his rank came in January, 1865.

Ironically, Beale was a reluctant soldier who chafed against the pettiness and administration of regular army life and who regularly threatened resignation. He offered once to command guerillas or even revert to the rank of private. His superiors always persuaded him to remain at his post. By the end of the war, he had become an outstanding commander of cavalry.

Following the war he went home to Hague, Virginia to practice law and involving himself in editing and local politics. He decided to run for Congress again and was elected as a Democrat to finish the term of fellow Virginia cavalryman, Beverly B. Douglas, who had died in office. He was reelected to a full term in the next Congress and served from 1879 to 1881. After leaving Congress again, he returned to his practice and the writing of a history of the Ninth Virginia, which was posthumously published by his son George.

Richard Lee Turberville Beale died in Westmoreland County on April 18, 1893 and was buried in the family plot at Hickory Hill. He was seventy-three years old.

Here’s to forgotten Confederate cavalry and Dickinson College alum Richard L. T. Beale.

Scridb filterI’m pleased to introduce a guest blogger for a forgotten cavalrymen profile. My friend Tonia J. “Teej” Smith has spent years researching the saga of the hanging of Col. Orton Williams and his cousin, Walter “Gip” Peter as spies at Fort Granger, near Franklin, Tennessee. Williams was a cousin of Mrs. Robert E. Lee, and the hanging hit the Lee family hard. Here’s Teej’s profile of forgotten cavalryman Orton Williams.

Col. William Orton Williams, P.A.C.S.

Orton Williams was born in Buffalo, New York on July 7, 1839, the son of Captain George W. Williams of the Topographical Engineers and America Peter Williams, a Georgetown socialite. Through his mother, he was a direct descendant of Martha Washington and a cousin of Mary (Mrs. Robert E.) Lee.

By the age of seven, Orton had lost both of his parents. His father was killed at the battle of Monterey in Mexico and his mother died April 25, 1842.* Mary Lee’s father, George Washington Parke Custis, became the boy’s guardian so he grew up both at Arlington and at Tudor Place, his family home in Georgetown.

Like his boyhood idol, Robert E. Lee, Orton attended the prestigious Episcopal High School in Alexandria Virginia. He hoped then to follow in his father’s footsteps and attend West Point but was prevented from doing so by a rule which prohibited brothers from attending the Academy. His brother Laurence had graduated from there in 1852. His sister Markie, however, mounted a campaign on his behalf which included shamelessly reminding everyone involved that their father had died a hero’s death. With this, she managed to secure him the coveted appointment, though curiously, he never accepted it, instead taking a job, with the Coast Survey Service in 1858.

In 1860, R.E. Lee sought a direct commission for his young protégé. On March 23, 1861, Williams was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in Lee’s own regiment, the Second Cavalry, and was assigned to Gen. Winfield Scott’s staff. Scott took an immediate liking to the young man. Within a month Orton was promoted to 1st lieutenant and became Scott’s private secretary.

His duties allowed him to spend considerable time at Arlington, much of which may be explained by his romance with Agnes Lee. Indeed, most people expected the two to marry. When Colonel Lee resigned from the army and “went South,” however, General Scott insisted that Williams cease his visits to the Lee home. Despite Scott’s order, Orton went to Arlington on May 4 to warn Mary of the impending seizure of the heights around Arlington. Upon his return to Washington, he made known his intent to resign and offer his sword to the Confederacy. Scott immediately had him arrested and incarcerated at Governor’s Island, New York. He was released several weeks later when it was deemed that any information he might have was no longer of value to the Confederates.

On June 10, 1861, Lieutenant Williams again tendered his resignation. This time it was accepted. He served briefly on Lee’s staff but when rumors began to circulate that Lee had placed him in Scott’s office to spy, Orton transferred to the staff of Gen. Leonidas Polk at Columbus, Kentucky. It would not be the last time that the word “spy” was coupled with his name.

Shortly after his arrival, he wrote to his cousin Walter “Gip” Peter and asked him to seek a transfer west. Gip was serving as one of Lige White’s scouts in the Leesburg, Virginia area. Ignoring his sister’s warning that Orton was dangerous, Gip asked for and got the transfer. It is possible that Williams wanted his cousin and friend with him because he was not well liked by his fellow officers, most of whom saw him as arrogant and condescending. Williams added to his poor reputation when he killed an enlisted man for refusing an order. His defense for what can only be called murder was “For his ignorance, I pitied him; for his insolence, I forgave him; for his insubordination, I slew him.” There is no evidence that any formal charges were ever brought against him. Nevertheless, Orton Williams became a pariah among officers and men alike. Shortly after the incident, he legally changed his name to Lawrence Williams Orton and was transferred to Gen. Braxton Bragg’s staff.

Following the battle of Shiloh in which Williams received written praise from Bragg and an engraved sabre from P.G.T. Beauregard, he was promoted to colonel and given command of Second Brigade of Maj. Gen. W.T. Martin’s Division of Cavalry. Gip became his adjutant. His cousin’s letters home that final spring indicated that Orton was doing well and anticipating a promotion to brigadier general. Two letters, one written by Robert E. Lee to Orton on April 7, and the other a few days later by JEB Stuart to an unnamed colonel who clearly was Orton, seem to verify that Williams was not only going to be promoted but was coming back to Virginia to serve under Stuart.

Orton’s change of fortune makes what happened next very puzzling. Shortly before sundown on June 8, 1863, Orton and Gip, dressed as Union officers, rode into Fort Granger, near Franklin, Tennessee and presented papers to the fort’s commander, Col. J.P Baird, which introduced them as Col. Lawrence W. Auton and his aide, Maj. Walter Dunlop, sent from Washington to inspect all the forts in the area. Baird’s subordinates were suspicious of the strangers but he accepted their story at face value, giving them the password that would insure their safe passage to Nashville and even loaning them $50.

Eventually, Baird contacted Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans at his headquarters in Murfreesboro about the pair. By the time he received word that they were imposters, they had already left the fort. He quickly dispatched Col. Louis B. Watkins, 6th Kentucky Cavalry, to bring them back. Under intense questioning, they admitted they were Confederate officers but denied that they were spies.

Upon instructions from Rosecrans’ chief of staff, Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield, Baird called a drumhead court martial. Within thirty minutes the men were found guilty and sentenced to hang the following morning. To the end, they continued to deny they were spies. In a cryptic letter to Agnes Lee, Williams spoke of marrying her in Europe within a month had not “the fate of war decided against us. I have been condemned as a spy—you know that I am not.”

Both men met death with such bravery that the entire garrison was impressed with their courage. Baird publicly expressed the view that whatever mission the men were on, it did not involve Fort Granger. All else remained a mystery to him as it does to historians to this day. A year later their families were allowed to bring their bodies back to Georgetown for burial in the family plot in Oak Hill Cemetery.

* Author has been unable to discover the cause of Orton’s mother’s death but I strongly suspect it was due to complications following childbirth.

Thanks, Teej. There’s much more to the saga, of course, and much more to the Williams family story, but I will leave it to Teej to tell that story.

Scridb filterSusan and I got up yesterday morning at the ungodly hour of 4:00 a.m. to catch a flight to Richmond. I was invited to be the speaker at the commemoration of the anniversary of Jeb Stuart’s birth by the Stuart-Mosby Historical Society. There was a commemoration at Stuart’s grave in Hollywood Cemetery, and then a luncheon at a lovely place called the Commonwealth Club. Susan did a good job of acting as photographer; these are her photos. Fortunately, it was 67 degrees in Richmond yesterday, and it was really nice being able to walk around without a coat in early February.

Detachments of two different reenacting groups provided honor guards. One was a fife and drum corps and the other a regimental color guard. Both were quite authentic, and both did a fine job.

I’m told that there’s usually a cannon at the commemoration, but that they could not make it at the last moment. Instead, the color guard fired three volleys in General Stuart’s honor.

I found out yesterday morning that not only was I to speak at the luncheon after the graveside ceremony, I was also expected to say a few words at the cemetery. I had no idea of this until about twenty minutes before it happened, so I had to wing it. I guess I did okay.

After a nice lunch, I gave the assembled members my rendition of the events covered in Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. I’m pretty sure I’m coming down with something, and my voice was pretty rough. I’m just glad it held out.

Last night, we had dinner at The Tobacco Company Restaurant in the Shockoe Slip district of Richmond with old friend Melissa Delcour, whom we haven’t seen in ages. We had a terrific dinner getting caught up with Melissa, and then it was to bed early to get up at 4:30 to make our return flight to Columbus this morning. We were gone for 26 hours, and it was chaotic. Thanks to Skybus, we were able to fly directly into Richmond for a very inexpensive airfare ($110 roundtrip for each of us) instead of all of that driving.

Needless to say, I’m not used to being up that early, let alone that early two days in a row. I suspect we’re all headed to bed early tonight……

The great Battle of Brandy Station was fought on June 9, 1863. 12,000 Union cavalrymen splashed across the Rappahannock River at Beverly’s Ford and Kelly’s Ford to strike at Confederate cavalry thought to be near the town of Culpeper. They were surprised to find the enemy right across the river. Although the Confederate troopers were surprised by the bold attack, they rallied and held their own, keeping John Buford from taking the guns of the vaunted Stuart Horse Artillery. A fourteen hour battle raged, with Alfred Pleasonton, the Federal cavalry commander, eventually breaking off and withdrawing, leaving the battlefield in Stuart’s hands.

Pleasonton had received orders to march with his whole command and break up or disperse the large concentration of Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County, and he failed miserably. He also left the battlefield in Stuart’s hands, meaning that Brandy Station has to be considered a Confederate victory by any measure, both tactically and strategically.

Nevertheless, Stuart was excoriated by the Richmond newspapers for having been caught by surprise and for taking heavy losses in the long battle. Many amateur psychologists, most notably Emory N. Thomas, in his biography of Stuart, Bold Dragoon, have contended that Stuart’s surprise and angst over the criticism motivated him to want to do something spectacular to redeem himself, thereby triggering the “ride” during the Gettysburg Campaign. While I hope that J. D. and I have refuted that myth, there’s nothing like the letter that is the source of that theory. So, here’s Stuart’s letter to his wife Flora, responding to the allegations that he was badly surprised and badly beaten. Where something appears in [brackets], I’ve added an explanatory note to help put this letter into better context for you. Most of the officers he refers to in the letter, unless otherwise designated, were part of Stuart’s staff. The underlining is in the original. It makes for an interesting read.

Camp Farley

June 12th, 1863

My Darling Wife:

God has spared me through another bloody battle, and blessed with victory our arms. The fight occurred on the 9th between Brandy Station and will be called “Battle of Fleetwood Heights.”

We mourn the loss of [Capt. Will] Farley, my volunteer aide, killed, and [Maj. Benjamin S.] White wounded painfully. [Lt. Robert H.] Goldsborough was captured taking an important order to [Col. Williams C.] Wickham [,the commander of the 4th Virginia Cavalry]. I hope he was not hurt–he behaved most gallantly. General William H. F. Lee, with his whole Brigade, distinguished themselves, fighting almost entirely against regulars. I have no time for a detailed report to you. The papers are in great error, as usual, about the whole transaction. It was no surprise. The enemy’s movement was known and he was defeated. We captured three pieces of Artillery which the Horse Artillery now have. Lieutenant Colonel [Frank] Hampton [of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry] was killed–also Colonel Sol[omon] Williams [of the 1st North Cavalry] and a number of brave spirits who will be deeply mourned. Our entire loss does not exceed 500 killed, wounded and missing. Among the wounded are General William H. F. Lee, Lieutenant Colonel [Jefferson] Phillips [of the 13th Virginia Cavalry], Colonel [Matthew C.] Butler [of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry] (whose foot was amputated). It is considered certain that [Col. Benjamin F.] Grimes Davis (Yankee) was killed (he commanded a Brigade) and that [Col.] Percy Wyndham was wounded

Colonel [Pierce M. B.] Young [of the Cobb Legion Cavalry] made a splendid charge. Fitz Lee’s Brigade did not see much execution as it was but little engaged.

General [Robert E.] Lee reviewed the Division the day before the fight. I have not seen [Lt. Col. C. H.] Tyler since you left. [Col. Thomas L.] Rosser’s regiment [the 5th Virginia Cavalry] was absent. The Richmond Enquirer of the 12th lies from beginning to end. I lost no paper–no nothing–except the casualties of battle. I understand the spirit and object of the detraction and can, I believe, trace the source. I will, of course, take no notice of such base falsehood.

Your friends are all well except those referred to. I received a very affectionate letter from Mrs. Price about [Lt.] Thomas [Randolph Price, Jr.] leaving me [due to personality conflicts with Stuart, he was transferred to Jubal Early’s staff]. I will answer it in the right spirit but I do not regret that I did it. The very day you left I received marching orders but they were countermanded. I am now in a nice grove near the Review ground. I lost nothing whatever. The Examiner to the contrary notwithstanding. I believe it all originates in the Salt question. You must be careful now what you say. Give much love to all friends. [Maj. L.] Frank Terrill has reported to the War Department for orders. Captain [J. L.] Clark has been chosen as Captain of Gilmer’s Company, 12th Virginia Cavalry and I am free again. Weaver has returned from amongst the Yankees; they acknowledge themselves whipped badly. Davis killed, Wyndham mortally wounded. [Brig. Gen. Alfred] Pleasonton wrote to me and asked leave to bury his dead and care for his wounded. I replied that I had attended to both. He commands [Maj. Gen. George] Stoneman’s Corps now. Kiss Jimmy.

Your Own,

J. E. B. Stuart

P. S. Captured Buford’s aide [Capt. Joseph O’Keeffe].

This letter has triggered a vast amount of speculation. Read it and decide for yourself. For me, however, there is nothing in here that suggests that Stuart was anything but angry about the way he was portrayed in the newspaper accounts of the battle. I see nothing that suggests he was so bent out of shape as to feel the need to do something to “redeem himself”.

Scridb filter 143 years ago today, the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps clashed with Fitzhugh Lee’s division of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps a few miles north of Richmond at a place called Yellow Tavern at the intersection of the Telegraph and Mountain Roads. After a long, hard fight, the men of Brig. Gen. Williams C. Wickham’s brigade began giving way in the face of a determined attack by George Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, the Confederate cavalry chief, dashed forward to try to rally his troopers and received a mortal wound to the abdomen from one of the Wolverines. Stuart died in Richmond the next day after a long night of suffering. When Robert E. Lee heard of Stuart’s death, he wept and was heard to say, “He never brought me a wrong piece of information,” which was, perhaps, the ultimate compliment Lee could have paid the fallen cavalier.

143 years ago today, the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps clashed with Fitzhugh Lee’s division of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps a few miles north of Richmond at a place called Yellow Tavern at the intersection of the Telegraph and Mountain Roads. After a long, hard fight, the men of Brig. Gen. Williams C. Wickham’s brigade began giving way in the face of a determined attack by George Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, the Confederate cavalry chief, dashed forward to try to rally his troopers and received a mortal wound to the abdomen from one of the Wolverines. Stuart died in Richmond the next day after a long night of suffering. When Robert E. Lee heard of Stuart’s death, he wept and was heard to say, “He never brought me a wrong piece of information,” which was, perhaps, the ultimate compliment Lee could have paid the fallen cavalier.

Jeb Stuart was perhaps the finest all-around cavalryman ever produced by the United States Army. Stuart had a real gift for the traditional roles of cavalry, scouting, screening, and reconnaissance, and did it better than anyone has before or since. He was quite literally the eyes and ears of the army, and Robert E. Lee leaned harder on Stuart than on any other subordinate except perhaps James Longstreet. I genuinely believe that this explains Lee’s being so disconcerted at Gettysburg–not because the cavalry wasn’t there, but rather because the man he depended upon most heavily for accurate information about the enemy was not there. In May 1864, Stuart was 31, at the height of his fame and glory, and was known as the laughing cavalier. He had a real zest for life, and he loved to sing, flirt with the ladies, and always had a good time. His personal theme song, “If you want to have some fun, jine the cav’ry” certainly sums up his philosophy of life–fun.

At the same time, Stuart could be serious as a heart attack when he needed to be. He was capable on the battlefield, and did a magnificent job handling a huge infantry corps at Chancellorsville after Jackson received his mortal wound. In short, this man was flat out competent at virtually everything he did.

That’s not to say he was without flaws.  Prideful, ambitious, and always looking for an opportunity for personal glory, I tend to think that Stuart fell at just the right moment. He tended to be prone to clash with subordinates who did not appreciate his personality (see Grumble Jones, Beverly Robertson, and even Wade Hampton for good examples of what I mean here), and was very sensitive to slights, both imagined and real.Â

Because of what happened at Yellow Tavern that warm May day, Stuart will be forever the gallant young hero, struck down at the height of his fame, a symbol of the Confederacy. I suspect that had he lived, Stuart would have had a difficult time adapting to the changing and evolving role of horse soldiers. By the spring of 1864, with its men armed with repeating carbines that laid down a great deal of fire power, and with new commanders, the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps was becoming a potent offensive weapon and de-emphasizing the traditional roles of the cavalry, scouting, screening, and reconnaissance. I don’t know that Stuart would have been able to adapt to these changes and maintain his luster. Stuart symbolized the early days of the war–chivalry, fun, decorum–in other words, war as a grand adventure to be enjoyed. Wade Hampton, a solid fighting man, adapted well to dismounted fighting that closely resembled infantry tactics, but I rather doubt that Stuart would have been able to make that transition cleanly or easily. I suspect that, had he lived, much of the luster would have rubbed off.

When Stuart fell, some of the spirit left the Army of Northern Virginia forever. Its Cavalry Corps would never be the same again. Fortunately, Hampton was extremely competent in his own right, and he earned permanent command of the Cavalry Corps through his superb battlefield performance.  Make no mistake, though: it was no longer jine the cav’ry if you want to have some fun. Hampton was a grim, serious warrior, and he had none of the sense of fun possessed by Stuart.  Hampton’s serious, hard-hitting style was a stark contrast to Stuart’s lightheartedness, but it was just what was needed at the time. By May 1864, the war had become a stark war of attrition, and it was a very serious business. It needed a serious response, and Wade Hampton was just the sort of hard fighter to give that serious response. Like Stuart, Hampton was the right man at the right time.

Here’s to Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart, the legendary Virginia cavalier who redefined mounted operations, who received a mortal wound at the Battle of Yellow Tavern 143 years ago today. Â

Scridb filterA reader named Don Hallstrom posted a comment that was buried deep in a thread that I posted a year ago. If WordPress didn’t notify me whenever a comment is posted to this blog, I probably never would have noticed it.

Here’s what Don wrote:

I recently purchased a couple of your books and look forward to reading them. This portion of your blog relating to confederate cavalary has raised my interest in other lesser know leaders. I agree with your opinions about Thomas Munford and enjoyed reading them. I wanted to see if you were going to post some others. What do you think about the following:

Laurence Baker

Lunsford Lomax

James B. Gordon

John Chambliss

Pierce M.B. Young

I realize Young and Gordon have had biographies done on them(unsure of the quality). Wondered if you thought any of the others might be good subjects. One other book I have in my collection that I’ve not gotten to is THE LITTLE JEFF- Hopkins. Hopefully, will provide some good reading.

Regards

Don

Thanks for your kind words about my work.

I thought I would answer your question here in a separate post, instead of in the comments to a very old post.

You are correct that there is a biography of P.M.B. Young. It’s rather old at this point, and he could probably stand a modern treatment. I am not aware of a specific biography of James B. Gordon, although there is a very good history of his brigade by old friend Chris Hartley. The issue with Gordon, of course, is that he died in May 1864, and I have no idea what primary source material is available on Gordon himself, as opposed to his brigade.

Chambliss and Lomax both probably deserve bios. Chambliss, of course, was KIA in August 1864, but he was a West Pointer, and a very close friend of David McMurtrie Gregg. Chambliss played a very significant role in the evolution of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps, and commanded a brigade during its most important period. Lomax achieved the rank of major general and divisional command, and he was also a member of one of the First Families of Virginia.

Baker is a pretty minor player, and I think it would be extremely difficult to try to write a bio of him.

That I am no fan of Tom Rosser is no secret. I think Rosser was dramatically overrated and not an especially good soldier. Having said that, Rosser has one biography, and it’s not very good at all. Rosser needs a modern and scholarly biography if for no reason other than that he looms over much of the war in the East.

I hope that answers your questions. If you’re thinking of tackling one or more of these projects, good luck.

Scridb filterToday, J. D. Petruzzi’s blog features a post about one of my favorite primary sources, The Journal of the United States Cavalry Association, which was a professional journal for serving officers of the United States Cavalry. George S. Patton, Jr., an old horse soldier, was a regular contributor the Journal.

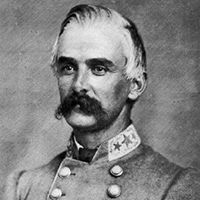

Another regular contributor was one of my favorite Confederate cavalrymen, Col. Thomas Taylor Munford. I’ve always believed that Munford got an incredibly raw deal from the Confederate hgh command. For one thing, he wasn’t a West Pointer, and for another, he wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with. At the same time, he was an extremely competent cavalryman who often commanded brigade and occasionally even a division as a colonel. He was often recommended for promotion by Stuart and Robert E. Lee, but the Confederate Senate never confirmed a promotion. However, that didn’t stop Munford from calling himself “general”.

Another regular contributor was one of my favorite Confederate cavalrymen, Col. Thomas Taylor Munford. I’ve always believed that Munford got an incredibly raw deal from the Confederate hgh command. For one thing, he wasn’t a West Pointer, and for another, he wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with. At the same time, he was an extremely competent cavalryman who often commanded brigade and occasionally even a division as a colonel. He was often recommended for promotion by Stuart and Robert E. Lee, but the Confederate Senate never confirmed a promotion. However, that didn’t stop Munford from calling himself “general”.

J. D.’s post has inspired me to select Munford for one of my periodic profiles of forgotten cavalrymen.

Here’s the biography of Munford that appears in Vol. 3 of Confederate Military History, pp. 639-641:

Brigadier-General Thomas Taylor Munford, a distinguished cavalry officer of the army of Northern Virginia, was born at the city of Richmond, in 1831, the son of Col. George Wythe Munford, for twenty-five years secretary of the commonwealth. He was graduated at the Virginia military institute in 1852, and until the outbreak of the war, was mainly engaged as a planter. He went into the Confederate service as lieutenant-colonel of the Thirtieth Virginia mounted infantry, organized at Lynchburg, May 8, 1861, and mustered in by Col. Jubal A. Early. This was the first mounted regiment organized in Virginia, and under the command of Col. R. C. W. Radford, was in Beauregard’s army at the battle of First Manassas. Subsequently it was entitled the Second regiment of cavalry, General Stuart’s regiment being numbered First, at the reorganization under Stuart, when Munford was promoted colonel of the regiment. On the field of Manassas he had commanded three squadrons composed of the Black Horse, Chesterfield, and Wise troops, the Franklin rangers, and three independent companies, and pursued the enemy further than any other command, capturing many prisoners and ten rifled guns, which he turned over to President Davis at Manassas. His career as a cavalry officer thus brilliantly begun continued throughout the war, and was notable for faithful service in whatever command was allotted him. In the spring of 1862, attached to Ewell’s command, he skirmished in Rappahannock county, and then joined Jackson in the Valley. Upon the death of General Ashby he was recommended by Gen. R. E. Lee as his successor. In this ,capacity he participated in the battle of Cross Keys, and captured many prisoners at Harrisonburg. With his regiment he led Jackson’s advance in the Chickahominy campaign, and o; the day of battle at Frayser’s farm, his men were the only part of the corps to cross the river and attack the Federals at White Oak-swamp. He joined Stuart’s command in the Manassas campaign, leading the advance of Ewell’s division, and received two saber wounds at Second Manassas. In September, assigned to the command of the brigade, he took part in the Maryland campaign, in which his men sustained the main losses of the cavalry division, fighting at Poolesville, Monocacy church, Sugar Loaf mountain, Burkittsville and Crampton’s gap. At the latter pass of the South mountain, with about 8oo men, dismounted, he made a gallant defense against the advance of a Federal corps. At Sharpsburg he was actively engaged on the 17th and 18th, on Lee’s right wing, guarding the lower fords of the Antietam, crossed the Potomac in the presence of the enemy, and defended the retreat from Boteler’s ford. In October, when the Federal army advanced in Virginia in two columns, he was put in command of one division of the cavalry to confront Hancock’s troops. Subsequently he was transferred to Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade, which he commanded after Chancellorsville at Beverly’s ford and Aldie. He took part in the Gettysburg campaign, the Bristoe campaign, and the cavalry operations in the spring of i864 under Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, participated in the Valley campaign with Early, and being promoted brigadier-general in November, 1864, was assigned to the command of Fitzhugh Lee’s division. In this rank he made a gallant fight at Five Forks, and on the retreat from Richmond was associated with General Rosser in the defeat of the Federals at High Bridge, capturing 780 prisoners; also in the battle of April 7th, when the enemy was again defeated and Federal General Gregg was captured. At Appomattox, at daybreak of April 9th, he commanded the cavalry on the right of the Confederate line, in the attack, and driving the enemy from his front, moved toward Lynchburg. After the surrender of Lee he endeavored to collect the scattered Confederate bands and make a junction with Johnston’s army, but after the latter command capitulated he disbanded his men late in the month of April. In his final report Gen. Fitzhugh Lee called attention to the excellent service of General Munford as a division commander. With the close of the war he retired to his home, and since then has been engaged in the management of agricultural interests in Virginia and Alabama, with his home at Lynchburg. He has served two terms as president of the board of visitors of the Virginia military institute.

In the years after the war, he ultimately settled in Uniontown, Alabama, where he was a planter. Munford died on February 27, 1918 at the age of 87.

I’ve always firmly believed that Munford got a raw deal. The simply fact is that he was an excellent soldier, unquestionably a better cavalryman than the likes of Thomas L. Rosser, who provides excellent proof of the truth of the Peter Principle. Somehow, Rosser, who was not competent to command a regiment, ended up a major general while Munford, who was a MUCH better soldier, never did receive a promotion to brigadier general.

Rosser and Munford detested each other. They spent the post-war years sniping at each other in print. One of these days, I’m going to do something on their decades-long feud. I’ve already got a title picked out: “There was no love lost: The Rosser/Munford Feud”.

Here’s to Thomas Taylor Munford, forgotten Confederate cavalryman.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like