Today, J. D. Petruzzi’s blog features a post about one of my favorite primary sources, The Journal of the United States Cavalry Association, which was a professional journal for serving officers of the United States Cavalry. George S. Patton, Jr., an old horse soldier, was a regular contributor the Journal.

Another regular contributor was one of my favorite Confederate cavalrymen, Col. Thomas Taylor Munford. I’ve always believed that Munford got an incredibly raw deal from the Confederate hgh command. For one thing, he wasn’t a West Pointer, and for another, he wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with. At the same time, he was an extremely competent cavalryman who often commanded brigade and occasionally even a division as a colonel. He was often recommended for promotion by Stuart and Robert E. Lee, but the Confederate Senate never confirmed a promotion. However, that didn’t stop Munford from calling himself “general”.

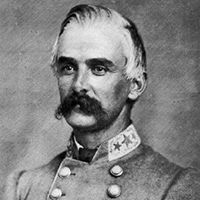

Another regular contributor was one of my favorite Confederate cavalrymen, Col. Thomas Taylor Munford. I’ve always believed that Munford got an incredibly raw deal from the Confederate hgh command. For one thing, he wasn’t a West Pointer, and for another, he wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with. At the same time, he was an extremely competent cavalryman who often commanded brigade and occasionally even a division as a colonel. He was often recommended for promotion by Stuart and Robert E. Lee, but the Confederate Senate never confirmed a promotion. However, that didn’t stop Munford from calling himself “general”.

J. D.’s post has inspired me to select Munford for one of my periodic profiles of forgotten cavalrymen.

Here’s the biography of Munford that appears in Vol. 3 of Confederate Military History, pp. 639-641:

Brigadier-General Thomas Taylor Munford, a distinguished cavalry officer of the army of Northern Virginia, was born at the city of Richmond, in 1831, the son of Col. George Wythe Munford, for twenty-five years secretary of the commonwealth. He was graduated at the Virginia military institute in 1852, and until the outbreak of the war, was mainly engaged as a planter. He went into the Confederate service as lieutenant-colonel of the Thirtieth Virginia mounted infantry, organized at Lynchburg, May 8, 1861, and mustered in by Col. Jubal A. Early. This was the first mounted regiment organized in Virginia, and under the command of Col. R. C. W. Radford, was in Beauregard’s army at the battle of First Manassas. Subsequently it was entitled the Second regiment of cavalry, General Stuart’s regiment being numbered First, at the reorganization under Stuart, when Munford was promoted colonel of the regiment. On the field of Manassas he had commanded three squadrons composed of the Black Horse, Chesterfield, and Wise troops, the Franklin rangers, and three independent companies, and pursued the enemy further than any other command, capturing many prisoners and ten rifled guns, which he turned over to President Davis at Manassas. His career as a cavalry officer thus brilliantly begun continued throughout the war, and was notable for faithful service in whatever command was allotted him. In the spring of 1862, attached to Ewell’s command, he skirmished in Rappahannock county, and then joined Jackson in the Valley. Upon the death of General Ashby he was recommended by Gen. R. E. Lee as his successor. In this ,capacity he participated in the battle of Cross Keys, and captured many prisoners at Harrisonburg. With his regiment he led Jackson’s advance in the Chickahominy campaign, and o; the day of battle at Frayser’s farm, his men were the only part of the corps to cross the river and attack the Federals at White Oak-swamp. He joined Stuart’s command in the Manassas campaign, leading the advance of Ewell’s division, and received two saber wounds at Second Manassas. In September, assigned to the command of the brigade, he took part in the Maryland campaign, in which his men sustained the main losses of the cavalry division, fighting at Poolesville, Monocacy church, Sugar Loaf mountain, Burkittsville and Crampton’s gap. At the latter pass of the South mountain, with about 8oo men, dismounted, he made a gallant defense against the advance of a Federal corps. At Sharpsburg he was actively engaged on the 17th and 18th, on Lee’s right wing, guarding the lower fords of the Antietam, crossed the Potomac in the presence of the enemy, and defended the retreat from Boteler’s ford. In October, when the Federal army advanced in Virginia in two columns, he was put in command of one division of the cavalry to confront Hancock’s troops. Subsequently he was transferred to Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade, which he commanded after Chancellorsville at Beverly’s ford and Aldie. He took part in the Gettysburg campaign, the Bristoe campaign, and the cavalry operations in the spring of i864 under Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, participated in the Valley campaign with Early, and being promoted brigadier-general in November, 1864, was assigned to the command of Fitzhugh Lee’s division. In this rank he made a gallant fight at Five Forks, and on the retreat from Richmond was associated with General Rosser in the defeat of the Federals at High Bridge, capturing 780 prisoners; also in the battle of April 7th, when the enemy was again defeated and Federal General Gregg was captured. At Appomattox, at daybreak of April 9th, he commanded the cavalry on the right of the Confederate line, in the attack, and driving the enemy from his front, moved toward Lynchburg. After the surrender of Lee he endeavored to collect the scattered Confederate bands and make a junction with Johnston’s army, but after the latter command capitulated he disbanded his men late in the month of April. In his final report Gen. Fitzhugh Lee called attention to the excellent service of General Munford as a division commander. With the close of the war he retired to his home, and since then has been engaged in the management of agricultural interests in Virginia and Alabama, with his home at Lynchburg. He has served two terms as president of the board of visitors of the Virginia military institute.

In the years after the war, he ultimately settled in Uniontown, Alabama, where he was a planter. Munford died on February 27, 1918 at the age of 87.

I’ve always firmly believed that Munford got a raw deal. The simply fact is that he was an excellent soldier, unquestionably a better cavalryman than the likes of Thomas L. Rosser, who provides excellent proof of the truth of the Peter Principle. Somehow, Rosser, who was not competent to command a regiment, ended up a major general while Munford, who was a MUCH better soldier, never did receive a promotion to brigadier general.

Rosser and Munford detested each other. They spent the post-war years sniping at each other in print. One of these days, I’m going to do something on their decades-long feud. I’ve already got a title picked out: “There was no love lost: The Rosser/Munford Feud”.

Here’s to Thomas Taylor Munford, forgotten Confederate cavalryman.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Thanks for bio… in my few short years of reading about the Civil War it has stood out to me that most frequently when a specific task was requested of Virginia cavalry it was Munford that the was the go-to guy. He seems to have been relied on to do the dirty work. Do you know if anyone has written a biography on him? I have been looking for one.

Keith,

Sadly, you will have to continue to look for one, because nobody has ever tackled a full-length bio of Munford even though there are several large collections of his papers out there to draw upon.

Eric

Rosser was a West Point ‘wannabe’. I think he was at the Point but did not graduate. As such, he was worse than actual West Pointers when it came to those who did not go there but who held places of command in the cavalry.

He hated partisans mostly because ‘Hanse’ O’Neill refused an order of Rosser’s that the wily and intelligent O’Neill believed detrimental to his command. Rosser said that ‘independent commands’ could not be made to fight – which, of course, was nonsense. His condemnation of such commands together with the obvious problems that many of them created in the areas in which they operated helped repeal the Partisan Ranger Act that had permitted many such independent commands – including the 43rd Battalion a/k/a Mosby’s Rangers – to come into being.

Rosser – who hated Mosby as much as Munford both for his partisan methods and his lack of a West Point pedigree – was smart enough to know, however, that Mosby was the darling of Stuart and very much admired by General Robert E. Lee as well as Secretary of War, James Seddon. Therefore, he kept his ‘sniping’ to Mosby’s command and methods rather than the man himself whom he ‘damned with faint praise’. In the end, only Mosby’s and O’Neill’s commands were ‘kept’ as functioning partisan commands although most independents paid no attention to the repeal of the PRA and continued to fight as usual. Elija White’s ‘Comanches’ were mustered into the regular army at that time but neither Mosby nor O’Neill wanted to go that route.

It is said that Lee spent more time keeping peace among his commanders than making war against the Union and that’s probably true. The Rosser-Munford situation is just one more reason that Lee was not able to make more of what he DID have and, indeed, given the clash of personalities that swirled around in the Army of Northern Virginia, one wonders how he made as much of it as he actually did!

General Munford graduated from VMI in July 1854 (not 1852) ranking 14th in a class of 24. (re. VMI Archives)

I am proud to have people write in honor of my grandfather’s grandfather. I am a direct descendent of Thomas Taylor Munford. I have just begun to learn of my blood past, as I was adopted at birth and a few years ago searched and found my lineage. Interestingly, the heroic blood of this calvary leader ran down generations, and his grandson, also named Thomas Taylor Munford, was a hero in the Battle of the Bulge during WWII:

Thomas Taylor Munford, a Platoon Commander for the 740th Tank Battalion in World War II from Las Cruces, New Mexico was awarded the Purple Heart whilst fighting in Germany in the battle of “The Bulge”. He was also awarded a Silver Star. His tank received an armor-piercing round, tore his leg to pieces and I understand he still managed to pull a wounded comrade to safety under fire and in his terribly injured condition. I was lucky enough to meet him before he died, and he was the humblest man I’ve known.

I was intrinsicly drawn to the military and spent 7 years in th US Marine Corps as an infrantryman in the 1980’s, even before I knew who my heroic grandfather and great-great grandfather were.

Ironicly, although raised as a Yankee in Iowa with my adopted family, since learning of my “confederate” past, I have lived as far south as an American can live – along the US/Mexico border! I would love to participate in re-enactments and stand in place of my great-great grandfather. Even if I need to go to Virginia! Anyone who could get me in touch with the right people to do that, please let me know. info@edgmexico.com

My G-grandfather George Minor Winn, served in the 5th Va Cav (64-65), co. G, sergeant,; He named his son George Munford Winn, who was born in 1865. No other “Munfords” known in our family.

My great grandfather, William S. “Billy” Overton was in the 3rd VA. Cavalry, Co. G and served with Col Munford at the Battle of Tom’s Brook where he was killed in action on Oct 9, 1864. If you have any information about my great grandfather or where he may be burried, I would appreciate it. Thanks

I am researching Thomas T. Munford for a possible biography of him. I have sent a book proposal to the publisher who is going to publish my biographies of Brig. Gen. Rufus Barringer and Maj Gen. Thomas L. Rosser. Any help with prewar or post war material on Munford will be greatly appreciated

Butch Barringer

butchbar@verizon.net

Update on my Thomas T. Munford biography: My manuscript should be completed this Fall. I founds lots of fascinating information about this competent cavalry commander. He was a good soldier and leader. Some surprises also,

Update – July 18, 2014My biography of Colonel Thomas T. Munford will be completed this Fall. It’s been fun researching this honorable cavalry commander. The draft manuscript is nearing completion. I need some good reviewers to help me with suggestions/comments on the manuscript before I can complete it.

Butch Barringer

I’m a Munford! I don’t really know if I’m a direct descendant, but my family told me we’re related to him…

Col. Munford was my father’s (Thomas Munford Boyd 1899-1985)grandfather. Dad,a UVa graduate,and long-time UVa professor of Law,was born in Roanoke,Va,but visited “the General”,as he was called in Lynchburg often,and was very fond of him,although the story was that,”the General loved a drink and the ladies,but hated grandchildren and cats…!”

With Dad (known as “Munny”Boyd)when talking about the General,it was always with a great deal of admiration and respect.