Author:

Three of my friends, including Mike Peters, from our CWRT, and I spent the day touring the battlefield at Perryville yesterday. I’d only been there once before, in 1994 or 1995, and Mike likewise had only been there once before. Tim was making his first visit, while Rory, our fourth, has been there multiple times. As you will see from the photographs, it was an absolutely magnificent day–lots of sun, blue skies, no humidity, gentle breezes, and about 80 degree temperatures. One could not have asked for any better weather for battlefield stomping.

The last time that I was there, there was only a fraction of the interpretation that’s present now, and thanks to the efforts of the CWPT, lots of land has been added to the park. It is important to note that the battlefield is a Kentucky state park, NOT a national park. Nevertheless, it’s gorgeous, mostly pristine, and has tons of interpretive markers and trails. There are, in fact, more interpretive markers on this battlefield than there are on a lot of the national parks, and I was really impressed by it.

Imagine a battlefield as rural and pristine as Antietam, about the same size, only without all of the monumentation that marks Antietam, and you have Perryville. The battlefield is narrow and very compact; there are places where opposing batteries were blasting away at each other from within cannister range. The battle was one for ridge line after ridge line; the ground undulates and is marked by one ridge after another.

There’s also a nice little visitor center with a decent selection of Western Theater books and some other trinkets (I added another pin to the collection on my CWPT hat), and a small museum with some well-presented exhibits.

We were fortunate enough to have a couple of West Point alums who are retired Regular Army officers with us for a a couple of hours, meaning we were able to get onto some private property and see some sites associated with the battle that we otherwise would not have seen, including the site where Sheridan disobeyed orders and brought on the battle. That was extremely helpful to helping us to understand how things proceeded once fighting broke out.

We easily walked 8 or 9 miles over some extremely hilly, undulating terrain. It was tiring, but we saw pretty much the entire battlefield. I came away from it with a much better understanding of this battle and how it developed and played out. I am going to re-read Ken Noe’s excellent history of the battle, and then I should really have a solid understanding of it.

This beautiful battlefield, with its gorgeous hills and dales and lovely views, could easily and rapidly become one of my very favorites. You can also easily see the entire battlefield in a single day, which is nice. It’s compact and accessible, and I highly recommend a visit.

A lovely view from Peters Hill, which was Phil Sheridan’s headquarters during the battle. The view in the distance is of the main battlefield. This is the position from where Sheridan gave the orders that brought on a general engagement in violation of his orders.

Our group, at Parsons’ Battery. From left to right: Tim Maurice, Mike Peters, Rory McIntyre, Clair Conzelman, Tasha Conzelman, and yours truly.

Starkweather’s Hill, from Parsons Battery. This was the highest point on the Union line, a position from which the Union troops were driven.

The monument to the Union soldiers on the battlefield near the Confederate cemetery.

The Union order of battle monument.

The monument in the Confederate cemetery. This is a mass grave with only two specific soldiers identified with their own headstones. The rest are apparently unidentified.

The Dye house, which served as Simon Bolivar Buckner’s headquarters during the battle.

Looking down on the Squire Bottom house from the main Union line.

A full shot of the Squire Bottom house. Bottom lost everything as a result of the day when the war visited his property.

This is a recent addition to the battlefield honoring Michigan’s contributions to the Battle of Perryville. It overlooks the Squire Bottom house.

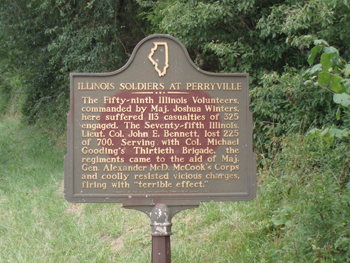

A similar marker honoring Illinois’ contributions to the Battle of Perryville. This is located very near the final Union line, at the Dixville Crossroads.

We encountered this cheeky llama at the end of the day, near the position that marked the final Union line of battle near the Davidson house. We determined that he is the sole surviving member of the 143rd Peruvian Llama Cavalry. 🙂

Scridb filterThe following article appears today on CNET. The speech that it discusses was given at a major cybersecurity conference going on in Las Vegas called Black Hat:

August 7, 2008 11:06 AM PDT

Cybersecurity lessons from the Civil War

Posted by Elinor MillsLAS VEGAS–The security issues we face today in cyberspace are the same ones the country faced during the American Civil War when Abe Lincoln was relying on telegraph transmissions to help keep the country united, a top U.S. cybersecurity official said in a keynote speech at the Black Hat security conference here Thursday.

Abe Lincoln, “the first wired president,” Beckstrom says. Lincoln was obsessed with reading telegrams that delivered updates from the battlefield, using them to learn about the military strategies and to offer feedback, said Rod Beckstrom, director of the National Cyber Security Center in the Department of Homeland Security.

“If he were alive today we would probably call him an e-mail junkie or a cyber junkie,” he said. “He was the first wired president; (telegraph) was a fixed wire” that could be severed or tapped.

Security lessons from battle were available even earlier in American history, according to Beckstrom. In the French and Indian wars, British forces relied on traditional warfare formations and often got slaughtered by French frontiersmen and their Native American supporters, who used guerrilla tactics like roadside ambushes.

One officer fighting on the side of the British who survived such attacks–George Washington–took the lessons of flexible fighting and guerrilla warfare with him in fighting for American independence, he said.

Even that American revolutionary war was almost lost because of “one of greatest threats we face today in cyberspace”–insider threats and hackers, Beckstrom said, displaying a portrait of Benedict Arnold, a disgruntled commanding officer who was passed over for promotion and charged with corruption after facing financial difficulties.

“He saw an opportunity,” and was selling plans for West Point and other military secrets to the British, but was caught in the end, Beckstrom said.

“We have the same threats today, just on different technology and mediums,” Beckstrom said.

Today, however, nations, businesses, and individuals also confront a single point of failure in cyberspace, with the Internet protocols and technologies, like the Domain Name System, he said. (A serious DNS vulnerability was the subject of a session at Black Hat on Wednesday.)

“Invest in protocols because it may be the cheapest security dollars we can invest,” Beckstrom said. The Department of Homeland Security is funding research related to DNS security, among other initiatives, he added. “We’ve got to move forward because we’ve got to change the odds of this game.”

The IP dependencies in the telecommunications sector put emergency communications, like mobile phone texting, at risk, Beckstrom said, noting that he was in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001, and in Pakistan when an earthquake hit and saw firsthand how crucial texting is. A cell phone tower can handle 200 or more calls simultaneously and about 5,000 text messages a second, according to Beckstrom.

And don’t forget the plain old telephone system, which will still be operational if the IP system goes down, he said.

Without elaboration, Beckstrom said: “Why can’t we quarantine computers that are disrupting the Internet?”

He touched on issues of punishment, “cyber justice,” and cyber diplomacy, and ended the talk asking more questions than he answered.

“What are the new cyber rules?” he asked. “How do we develop an international framework and move toward cooperation?”

Lincoln’s proclivities toward the telegraph have been well documented, most recently in a 2007 book titled Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. However, this is the first time that I’ve heard this particular analogy made.

The Civil War still permeates everything we do in this country.

Scridb filterAs I’ve mentioned here previously, I get an e-mail every time a comment is posted to this blog. Pingbacks from other blogs qualify as comments, and I get these regularly. The vast majority of those pingbacks are from splogs (spam blogs) and I immediately delete them as spam. Because of that, I check them carefully when they come in. Today, one came through from an interesting looking new blog. I checked it out and liked what I saw, so I’m adding it to the blog roll.

It’s got the intriguing name of Past in the Present, and it’s maintained by a fellow named Michael Lynch. Here’s how he describes himself: “I’m an East Tennessee native with a master’s degree in U.S. History and an interest in the American Revolution in the South. I’ve done a little college-level teaching, I used to do collections/exhibits at a Lincoln/Civil War museum, and I’m a former executive director at a late-1700’s historic house site.”

Welcome aboard, Michael. I’ve added a link from my blog roll.

Scridb filterThe following review of the new visitor center at Gettysburg by publisher Pete Jorgensen appeared in the most recent issue of the Civil War News:

The new Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park is not a museum at all and it has little on display regarding the battles of July 1, 2 and 3 in 1863.

It is a massive, attractively designed structure with vast amounts of exhibit space devoted not to exhibits, but to presentations. It also has a large gift shop operated by Event Network, a for-profit cultural attraction retailer.

The museum/visitor center is owned by a private, non-profit foundation which has engaged the National Park Service as groundskeepers, guides and guardians of the country’s largest collection of Civil War artifacts, which are stored away, far out of the visitor’s view.

Just before the “museum” opened, Gettysburg National Park Superintendent John Latschar tried to excuse the lack of exhibits and the identification of artifacts by saying of the old visitor center, “What we’ve got here right now is what is known as a collections museum. We’ve got rows and rows of rifles and pistols and cases full of battle debris, and zero story.”

He explained, “What we’re creating is a storyline museum, where you use artifacts to illustrate the storyline. So we have no need for 40 varieties of rifle muskets. We’re trying to provide our visitors with a basic understanding of the battle of Gettysburg in the context of the war and in the context of America….”

For 10 years people who have been involved in this project argued that the reason for building a new museum was that they had storage rooms full of more than 38,000 artifacts from the famous Rosensteel Collection and no room to display them.

Now that they have the room, they still have no interest in displaying them. We’d call this “museum fraud.”

This collection was started by John Rosensteel of Gettysburg who was age 16 in July 1863. In the 1890s he opened the Round Top Museum to display his collection to visitors. He expanded his collection by purchasing others and bought from local residents who had barns full of stuff from the battlefield.

In 1921, his nephew George Rosensteel opened the Gettysburg National Museum on land purchased from his uncle and continued buying up other Civil War artifact collections. His museum remained in private hands until 1971 when it was donated to the National Park Service.

At the former visitor center — the Rosensteel museum building — the Park Service displayed 6,633 artifacts from the Rosensteel collection. In April, when the new visitor center opened, only 1,338 artifacts were put on display, according to a Park Service news release.

That’s 79.8 percent fewer objects now exhibited than during the 37 years the Park Service has been responsible for the collection. It’s only 3.5 percent of the total artifacts locked away in storage.

We don’t even have to go to the definition of what the word “is” really “is” to unravel this outright fraud. Just pick up the dictionary — any dictionary — and look up the definition of the word “museum.”

You won’t find any definition for a “storyline museum,” nor will you find that a museum is “a place where stories are told.” No. That’s under “theater.”

The universally recognized arbiter of the language is the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary. It states: museum.n, A building or institution in which objects of historical, scientific, artistic, or cultural interest are preserved and exhibited. Also: the collection of objects held by such an institution. ?

There is no secondary definition of the word “museum.”

Gettysburg park officials apparently don’t know or don’t care what a museum is or what the general public expects to find in a museum. They built a “theater” to tell a “storyline” and now are trying to convince us that it is a new kind of museum that people who write dictionaries don’t know about yet.

Since this so-called museum isn’t designed to exhibit the 38,000 plus artifacts in storage at Gettysburg National Park, why keep them hidden? Why keep them at all? Let’s have an auction so that the people who value these objects can acquire them at market price.

What purpose is served by locking up thousands and thousands of Civil War muskets, rifles, carbines, shells, belt plates, uniforms, buttons, and all sorts of other stuff? Always the excuse has been “we don’t have the room to display it.” But now that they have the room, they won’t display it and we doubt many in the Gettysburg Park management can correctly identify any five objects in the collection selected at random.

That’s their problem, but it is our problem too. It’s a problem for the American taxpayer and the public in general. It’s a problem for the thousands of school kids who visit Gettysburg each year and the tens of thousands of visitors who think they will see some of the old guns, uniforms, bullets, cannon projectiles and other artifacts left behind after the battle. These are the things they expect to find in a museum.

We suspect park managers don’t know what they have, so they don’t know what is important to put on display and what is not.

For example, Gettysburg National Military Park has the best collection of Confederate 12-pounder bronze Napoleon cannon in the country. But not a single Confederate bronze Napoleon is on display in the “museum.”

All the Union 12-pounder Napoleon cannon look the same from a distance, regardless of maker, as all were made to a set of standard specifications. But there are five types of bronze Confederate Napoleons, all with distinct profiles.

On the field at Gettysburg you can pick out a Macon Arsenal Napoleon from 200 yards away, but you have to get closer to positively identify many others. Confederate Napoleons were made at Augusta Arsenal, Macon Arsenal and Columbus Arsenal in Georgia. And at the Tredegar Foundry in Richmond, Va., at Leeds & Company in New Orleans, at Quinby & Robinson Foundry in Tennessee and at a small cannon works in Charleston, S.C.

All of these represent different scientific and historical views on cannon design and economy of materials in the 19th century. That’s stuff you go to a museum to study and see first hand.

The first case in the museum’s display area contains a mixture of 26 Union and Confederate field artillery projectiles. None are identified. You’d never know which ones were used by which side or that each one actually does have a name, type and size associated with it.

Shells, solid shot, canister rounds, case shot, rifled and smoothbore ammunition are all mixed together. To everybody except a projectile collector the case is just a pile of old iron. And that apparently includes the National Park Service museum curatorial staff.

There are four more cases with 93 artifacts identified only as Civil War Firearms. But, again, there are no individual identifications as to Union or Confederate, carbine, rifle, or musket. One of these cases has 44 “pistols,” many of which are actually revolvers, not pistols. Each, of course, had a model, maker, type name, bore size and intended use, but there is no signage to tell anybody that.

A careful review of all 93 firearms confirms that nobody on the National Park Service staff knows anything about Civil War firearms and, worse, they don’t care if you do either.

One model infantry arm was ubiquitous during the four years of war — the Model 1861 Springfield Musket. They were everywhere. They were used in every major Civil War battle, carried for four years by half the Union army and they were also fired in hundreds of skirmishes between the forces of North and South.

Springfield Armory itself turned out more than 265,000 Model 1861 rifle muskets and 21 private contractors produced another 452,000 to the same government specifications.

In total, of the 1.5-million Union infantry rifle muskets produced, 717,000 were Model 1861 Springfields.

The number on display among the 93 firearms in the Gettysburg Museum’s display lobby: Zero.

That’s right. Zero. We counted and examined the cases three times.

Zero Model 1861 rifle muskets.

It’s like a man in charge said, “Hey, Jim, go down to the basement and get some guns to fill up those display cases.” And Jim said, “Which ones do you want, John?” And the reply could have only been, “Long ones, medium ones, short ones — mix ‘em up to get a good representative sample.”

It’s not only incredible, it’s ironic.

This place claims to be the Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park, and as a museum it can’t find the space to display a single example of the one model of rifle musket that was used by nearly half the Union infantry.

According to the Gettysburg Foundation’s Web site, the following was listed as the primary goal of the new building:

“Protection of the park’s collection of artifacts and archives: The park owns collections of 38,000 artifacts and 350,000 printed texts, historic photographs and other archival documents. New facilities are needed to provide appropriate storage conditions, proper care, and display of the collections.”

Well, there is no question they haven’t met their goal when it comes to the part about “display of the collections.”

Another case along the walls contains buckles, saber belt plates and buttons. There is one standard U.S. officer’s saber belt plate, one General Officer’s 3-piece wreath plate with stippled gold-leaf plating, but not a single one of the common enlisted cavalryman’s or artilleryman’s plate with a two- or three-piece silver leaf design surmounting a brass eagle.

Actually, there might be an example of the most common saber belt plate of the Union Army but it is hard to tell. In one glass case there is a field dug, tarnished and corroded belt plate that’s nearly impossible to identify. You just can’t see which applied silver leaf design it may have had, if any.

And one more — just one more — example. The oval Confederate brass enlistedman’s belt plate with a surmounted five-point star, and identified in Steve Mullinax’s book Confederate Belt Buckles & Plates on page 164 as Plate No. 299, is one of the few artifacts in the display cases with a little identification sign. It reads, “Union Militia Belt Plate” GETT #28220.

Mullinax, known for years as the country’s most informed expert on Confederate belt plates, must be wrong. The Gettysburg Museum of the American Civil War (its official name), managed by the National Park Service, apparently knows more about Confederate belt plates than the guy who wrote the book. But if Mullinax is right, that plate is worth $3,000 today and nobody will ever know it.

Just where does one go to study an exhibition of objects having scientific and historical value? All dictionaries say these objects are to be found in a “museum.” But not at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum.

There you will be charged $8 to see a film entitled “A New Birth of Freedom” that is full of its own errors, and you’ll walk through corridors with mannequins wearing reproduction uniforms, sitting on plaster horses. Then you’ll see some short film clips of the battle as you pass from room to room enjoying the “visitor experience.”

Soon, you’ll arrive at the Bookstore, Gift Shop and Refreshment Saloon, primed to open your wallet again to capture the flavor of the Civil War and perhaps your own stuffed soldier.

It is really unfortunate that those entrusted with the acquisition, conservation, study, exhibition and educational interpretation of objects having historical value have no clue as to their public responsibilities.

They are running a theater, not a museum. And they are public employees whose salaries and benefits are paid by your tax dollars.

If these new facilities were built for theater, the public should start demanding that the nation’s largest publicly owned collection of Civil War artifacts be sold — or that a museum be built to house, conserve, study, exhibit and interpret them.

Yes. A museum. Build a museum. What a novel idea.

In fairness, it should be noted that Pete visited before the identification tags were placed on the artifacts in the exhibits. They are now properly identified.

I happen to agree with Pete’s assessment of the place. I find it a real tragedy that the massive Rosensteel collection will probably never be seen in anything close to its full glory ever again. Sure, the artifacts are preserved, but so what? If nobody sees them or even knows they exist, what good are they?

All of the extraneous stuff in the museum is nice, but I would rather see the artifacts from the battle rather than a comprehensive narrative of the Civil War. Leave that to the new museum at Tredegar, or the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Instead, let’s focus the Visitor Center on Gettysburg.

Scridb filterThe following article appeared in last Friday’s edition of the Hanover Evening Sun newspaper, about how the new Gettysburg Visitor Center–of which I am not a fan–is harming the businesses that line Steinwehr Avenue:

Steinwehr business: Gettysburg visitor center move hurts strip

By ERIN JAMES

Evening Sun Reporter

Article Launched: 08/01/2008 09:36:10 AM EDTGettysburg business leaders are bracing for the potential negative impact of the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center’s recent move away from Steinwehr Avenue by pursuing a revitalization project of the tourist hub.

In fact, that was the premise of a grant application submitted by Main Street Gettysburg to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said USDA spokeswoman Rosemarie Massa.

On Thursday, the federal agency announced it will award $70,000 in grant money to “complete a revitalization plan for the small businesses which will be negatively affected by the relocation,” according to a USDA press release.

Main Street Gettysburg executive director Deb Adamik said the visitor center’s move is not the only reason Steinwehr Avenue is in need of funding, but it is the most obvious, she said.

“You’re taking a base of thousands of visitors farther away,” she said.

Gettysburg officials, headed by Main Street, announced in June that they had secured $215,000 toward the project’s planning phase, but they didn’t specify at the time where the grants were coming from. Adamik said Thursday that the USDA’s $70,000 was included among the original total and that the sources of other grants would announce their own donations at a later time.

The potential for tourists to abandon Steinwehr Avenue as a shopping destination now that the visitor center has moved was vaguely mentioned as a reason for beginning the revitalization project when it was announced in September 2007 and when its status was updated in June. The street is due for a new look and new infrastructure, planners said.

But Massa said the gist of Main Street’s application to the USDA suggests a stronger sentiment among business leaders to address growing concerns about the visitor center’s move.

Fears about declining business on Steinwehr Avenue as a result of the visitor center’s move date back to the project’s planning phase.

At that time, the National Park Service came under attack from residents and business owners concerned the facility would lure tourists away from the downtown area and already established tourist sites along Steinwehr Avenue – just down the street from the visitor center’s original location.

In response, park Superintendent John Latschar said the Park Service was committed to creating a shuttle system to take tourists to the Eisenhower National Historic Site and into Gettysburg. And he said he believed the new facility would encourage visitors to extend their stay and spend more money around town.

Groundbreaking on the new site off of Hunt Avenue and Baltimore Pike commenced in summer 2005, and the visitor center opened April 14 of this year.

But when tourism season kicked off in May, many Steinwehr business owners wouldn’t say whether they expected the visitor center’s move to negatively impact the street. Some even said they felt the potential impact had been overestimated.

At the time, the head of the Steinwehr Avenue Business Alliance said it was “too early to tell.”

But earlier this week, Tom Crist said there’s evidence the original fears were well-founded.

In fact, he attributed this year’s slow business to two reasons – the state of the economy and the opening of the new visitor center.

“(Tourists are) not coming down Steinwehr Avenue right now,” said Crist, who owns Flex and Flanigan’s at 240 Steinwehr Ave.

Adamik said she hasn’t spoken with “too many” business owners yet about the impact so far of the visitor center’s move.

But she suspects the economy is the “overriding issue” in preventing visitors from spending money downtown.

“They just don’t have as much money as they used to as disposable income,” she said.

Contact Erin James at ejames@eveningsun.com.

This doesn’t surprise me a bit. The first time that I saw the junk store in the new VC that masquerades as a book store, I knew it was going to do substantial harm to the local businesses that have drawn on the tourist trade for years.

It’s really no wonder that a lot of the local citizenry hates the battlefield:

* The Park is not always the best neighbor, as evidenced by the harm being done to the local businesses.

* The needlessly large Harley Davidson dealership owned by local blood sucking leech David LeVan brings vast amounts of noise and debauchery to a small town that neither wants nor needs it.

* LeVan, who just doesn’t know when to quit, remains absolutely determined to bring gambling to Adams County in the form of a horse track and slot machine casino, even though his last attempt to do so went down in flames by a large margin at the polls.

* Tourist traffic causes gridlock in the town and makes it impossible to find a parking space or a table in a restaurant at times.

There’s plenty more, but you get the point. While the old VC was long past its prime and had to go, the current thing is not what anyone needed. There will be more to say about that later.

Scridb filterI’ve known for some time that our book One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 was being considered by the History Book Club and the Military Book Club.

Ted Savas has today announced that both book clubs have chosen One Continuous Fight to be offered to their members. This is exciting for a lot of reasons. It means that the book will get a great deal of exposure it might not otherwise have gotten, any books purchased by them are non-returnable (which is a good thing), and only worthy publications are selected by the book clubs. Even though One Continuous Fight has sold well since the moment of its release, this will mean even greater sales.

Another of my books, The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Last Campaign, published in 2006, was also selected by both of the book clubs, and both substantially boosted the sales of the book. And, it’s a very cool thing to see my work featured in the mailers that the book clubs send out each month. It very much says that you’ve made the grade as a historian, and that’s really a gratifying thing.

So, thanks to Ted’s excellent work promoting and selling the books that he publishes, we’re going to be offered by the two book clubs, and I’m very pleased by that. Thanks, Ted.

Scridb filterThe first published review of One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 appeared in today’s issue of the Washington Times newspaper. Here’s the review, which is quite fair and quite favorable all at the same time:

Travel with the cavalry on Gettysburg retreat

Authors bring to light a captivating storyREVIEWED BY THOMAS J. RYAN

Thursday, July 31, 2008THE RETREAT FROM GETTYSBURG AND THE PURSUIT OF LEE’S ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA, JULY 4-14, 1863

By Eric J. Wittenberg, J. David Petruzzi and Michael F. Nugent

Savas Beatie

$34.95, 519 pages, illus.

A long-neglected aspect of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Northern Campaign in June and July 1863, the Confederate army’s harrowing retreat from Gettysburg is beginning to receive the attention it deserves. This was a high-stakes event, the outcome of which would have a profound impact on the progress of the war.

In 2005, Kent Masterson Brown published an incisive study called “Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics, & the Pennsylvania Campaign.” As the title implies, this work emphasized the logistics of moving a large army in unfamiliar and unfriendly territory in an attempt to reach safety at the end of an arduous campaign while being closely pursued by the enemy.

When Civil War armies confronted each other, ordinarily the infantry was at center stage. When armies were on the move, however, the cavalry generally played the more important role. It screened and protected a marching army, and gathered information about the opposing force’s location and intentions.

“One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863” by Eric J. Wittenberg, J. David Petruzzi and Michael F. Nugent highlights and scrutinizes the Union and Confederate cavalries’ role in the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, and factors in the results of cavalry engagements in the overall outcome of the pursuit of Lee’s army.

Mr. Wittenberg has published a number of studies on Civil War cavalry actions (most recently “Rush’s Lancers” and “Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg”), and is recognized as one of the foremost scholars on this subject. Mr. Petruzzi also specializes in cavalry matters, and authored the Jeb Stuart book with Mr. Wittenberg. Mr. Nugent, a newcomer to the publishing field, brings credentials of military service as an armored cavalry officer. The benefit of three authors collaborating is reflected in the extensive research conducted to produce this study.

In the foreword, Civil War writer Ted Alexander reviews the lean historical record on this subject, and cites the heavy casualty count for cavalry during this campaign.

Military historian Noah Andre Trudeau, in the preface, laments the absence of “the full Lee versus Meade story.” He cites the lost opportunities that Lee and Union commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade experienced during the post-Gettysburg period – not the least of which occurred during the retreat. In essence, he frames the issue that is at the heart of the examination undertaken in “One Continuous Fight,” that is, whether Meade put forth sufficient effort to attack and destroy Lee’s army.

In the introduction, the authors point out that the cavalry of both sides bore the brunt of the fighting during the retreat. The title is derived from a Confederate cavalryman’s description of the march from Gettysburg as “one continuous fight.” The objective, therefore, was to link more than a score of cavalry engagements, and to explain the impact of each on the outcome of the Army of the Potomac’s pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Several of these engagements occurred at locations that may not be familiar to some, such as Monterey Pass, Williamsport, Funkstown, Hagerstown, Boonsboro and Falling Waters. In the context of Lee’s attempt to escape with his army still relatively intact, however, each of these battles or skirmishes had a bearing on the eventual outcome.

The authors take the reader on a wild ride through the Pennsylvania and Maryland countryside following lengthy wagon trains and the opposing armies. Conditions were for the most part extraordinarily poor, with heavy rains and inferior or nonexistent roads. The Confederate train, filled with thousands of men wounded at Gettysburg, sustained repeated attacks along the route, yet somehow most of the wagons arrived at the Williamsport destination.

Lee’s army, already reduced by about 28,000 casualties at Gettysburg, would suffer thousands more losses from deserters and those captured along the way. The Confederates had two major terrain obstacles. Initially they had to get across South Mountain safely, and eventually ford a rain-swollen Potomac River. In both cases, they relied on Stuart’s cavalry to keep the Union army at bay in the attempt to have Lee’s forces reach safety.

Whether fighting in the mountains or clashing in the valleys, the Union and Confederate cavalries showed their mettle. These troopers conducted operations with little time for rest and paltry rations. The authors introduce several of these heroes, citing their backgrounds and accomplishments. Many would be wounded or killed in combat along the way, their makeshift graves dotting the landscape.

Particularly captivating is the description of the classic struggle between Union cavalry commanders Brig. Gen. John Buford and Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick on the one hand and the forces Brig. Gen. John Imboden was able to cobble together on the other. They fought for possession of the Confederate wagon trains that had successfully reached Williamsport. The authors point out that the outcome of this battle was crucial to the fate of Lee’s army.

While the successive cavalry battles provided the excitement, the pending confrontation involving opposing infantry supplied the drama. As both armies settled near Williamsport, Meade and Lee were left with the wrenching decision of whether to reprise the bloody conflict at Gettysburg.

Detailed discussion of the military and political ramifications of potential choices makes for fascinating reading. The authors assess the respective commanders’ capacity to accept responsibility and manage stress under these trying circumstances. While their commanders pondered the options, a sizable majority of Union officers and enlisted men who went on record expressed a desire to attack the enemy and bring an early end to the war.

A feature of this study is the extensive research and use of primary sources to authenticate the findings presented. Facts and statements are documented with the words of participants recorded in letters, memoirs and official correspondence. This plus the inclusion of ample maps, photos and illustrations enhances the feeling of being close to the action. An appended order of battle aids in identifying military units, and the comprehensive bibliography will permit further investigation.

Given the depth of research, it is surprising that this study does not include a number of reports dated July 9-11 from civilian and military scouts of the Army of the Potomac’s intelligence staff known as the Bureau of Military Information.

These documents, located in files at the National Archives and published in available sources, were from BMI personnel who reconnoitered Lee’s army in the vicinity of Hagerstown and Williamsport and provided details of its location, disposition, defensive preparation, supply efforts, movements across the river, and the conditions in the area. These reports were by far the most detailed Meade had available about enemy plans and activities.

Also note that the figure cited by the authors of 12,000 Union cavalry at the Battle of Brandy Station should read just under 8,000, and recent scholarship provides satisfactory evidence that Imboden’s cavalry brigade had a strength of 1,300 to 1,400 rather than the 2,245 cited. These changes for the record do not detract from the exceptional research accomplished in this study.

Some bonuses are two separate driving tours that afford the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of the retreating Confederate army and its wagon trains along the hazardous routes they followed. The length involved along these somewhat parallel routes (about 50 and 65 miles respectively), that begin and end in the same locations, may dictate taking one route forward and the other in reverse to save time. A listing of GPS Waypoints for the Wagon Train of Wounded Driving Tour provides additional guidance.

Those with an interest in the critical 10 days after the Battle of Gettysburg will welcome this essentially eyewitness account based on voluminous personal descriptions and recollections. “One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863” should be at the top of everyone’s Civil War shopping list.

Thomas J. Ryan of Bethany Beach is past president of the Central Delaware Civil War Round Table.

That’s a very favorable review, and I couldn’t be more pleased about it. Hopefully, there will be more. Thanks, Tom, and I’m glad to know you enjoyed the book.

Scridb filterHat tip to Kevin Levin for bringing this to my attention (please be sure to read the interesting tributes to Alan in the comments to Kevin’s post).

I had an opportunity to meet Alan and spend some time with him over the years. We did several programs together over the years, and he was a regular attendee at Gabor Borit’s annual Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. A number of years ago, Alan had a devastating stroke that left him largely wheelchair bound. Although his body had failed him, his mind remained active and he retained a keen interest in the Civil War. Even after the stroke, he continued to come to CWI, sitting on the aisle in a special spot reserved just for him. Alan passed away on July 27 at age 85.

I particularly enjoyed talking with him. For one thing, he was an attorney with decades of experience, so we spoke the same professional language. Alan was an NLRB arbitrator, and he thoroughly enjoyed that role. In addition, he was an accomplished and universally respected Civil War historian. His history of the Iron Brigade is considered to be one of the great classics of Civil War literature, and for good reason. It was a great book that helped to pave the way for contemporary unit historians; many still use its approach as a model for the modern unit histories. And, most importantly, Alan was always willing to chat with anyone who came by, and he was unfailingly kind and generous to all. Through it all, he remained humble, friendly, and always approachable, even as his illness sapped his productivity as a Civil War historian.

As for me, his work had a profound impact on me. In 1991, his seminal work, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. This book, which has spurred vast amounts of controversy since the day it was published, broke new ground: it contradicted the Lost Cause mythology and instead argued that Robert E. Lee was a human being filled with ordinary foibles who was not perfect. Writing a brilliant legal brief, Alan argued that Lee was not a god, but just a man, imperfect and eminently human, and prone to mistakes and even to some unpleasant and not altogether likable personality traits. In short, the book was a brilliant and ultimately revolutionary work that had a great impact on the world of Civil War history.

As for me, his work had a profound impact on me. In 1991, his seminal work, Lee Considered: General Robert E. Lee and Civil War History. This book, which has spurred vast amounts of controversy since the day it was published, broke new ground: it contradicted the Lost Cause mythology and instead argued that Robert E. Lee was a human being filled with ordinary foibles who was not perfect. Writing a brilliant legal brief, Alan argued that Lee was not a god, but just a man, imperfect and eminently human, and prone to mistakes and even to some unpleasant and not altogether likable personality traits. In short, the book was a brilliant and ultimately revolutionary work that had a great impact on the world of Civil War history.

I read the book when it first came out and was blown away by it. And I remembered it.

Years later, when I decided to assess Phil Sheridan’s role in the Civil War, I used Alan’s Lee Considered as the model for my book Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. I very much modeled my approach on Alan’s and I was unabashed about saying so in the introduction to the book. In a lot of ways, Little Phil was my personal tribute to Alan and his work, and like Lee Considered, it’s generated a great deal of controversy. Like Alan’s book, readers either love it or they hate it; I frankly don’t care whether they love it or hate it. If readers reassess their opinions about Sheridan, then I will have accomplished what I set out to do. Alan took very much the same approach to his work, and to the same effect.

I owe Alan Nolan a great debt, and I will miss him. Rest in peace, Alan. While your presence will be missed, your legacy will live on.

They say that bad things come in threes. Our little Civil War community has lost Deborah Fitts, Prof. John Y. Simon and now Alan Nolan in a period of just three weeks or so. Let’s hope that there will be no more losses for a while. Our ranks are thin enough.

Scridb filterI’m back home after Mother of All Gettysburg Seminars. It was a jam-packed few days. Here’s a run-down on the event.

WEDNESDAY: I put half a day at the office and hit the road at little after noon. It took me 5.5 hours to get to Chambersburg. JD beat me there–his trip is shorter than mine–so he was waiting for me. We had dinner together, and then there was an opening session. After it was over, we went to visit the traveling bookshop set up by old friend Jim McLean of Butternut and Blue. I spent WAY too much money on books this trip. It was good to see folks such as Ed Bearss, Jeff Wert, Tom Clemens, Blake Magner, Sean Dail, David Martin, Andy Waskie, Patrick Falci, and others. I also finally got to meet fellow blogger Ethan Rafuse. I did some client work and got to bed at a reasonable hour.

THURSDAY: JD and I had a full-day bus tour of a portion of Stuart’s Ride. It’s basically the tour at the end of our book Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. We had about 20 people, and while we’ve got this tour down to a science at this point, it makes for a LONG day. I got to see the new Custer monument at Hunterstown, which is pretty nifty. We left at 7:00 and got back to the hotel in Chambersburg at 5:30. There was a dinner and then a bunch of additional sessions, including a panel discussion on George Gordon Meade that included Jeff Wert, Kent Masterson Brown, Ethan Rafuse, Rick Sauers, and me. That was lots of fun.

FRIDAY: Friday was a full day of lectures. Neither JD nor I could bear the thought of sitting through them on a nice day, so we went and did our own thing. We left early and headed to the Monocacy National Battlefield, as we were going to follow Jubal Early’s route to Washington. We stopped into the new visitor’s center there, and, having forgotten that my pocket had a big hole in it, lost my digital camera. Fortunately, the ranger found it and kept it for me, but it meant I didn’t have a camera that day, which made me mad.

We followed the Georgetown Pike into DC, and then went to Rock Creek Park. Ranger Ron Harvey gave us some useful information there, and we then went and found the nearby and well-preserved Fort DeRussy, which was one of the circle forts around Washington, and which is remarkably well preserved. It saw action during the attack on Fort Stevens.

From there, we went and found what’s left of Fort Stevens. There’s not much there, but it was nevertheless cool to see the spot where Lincoln stood (which is not where the marker is, but rather where the dumpster is–not very dignified). From there, we went to nearby Battleground National Cemetery, which holds the remains of 41 men killed during the fighting for Fort Stevens, as well as four handsome regimental monuments. It’s the smallest national cemetery, but a cool site nevertheless.

After lunch, we went to Abraham Lincoln’s cottage on the grounds of the Soldier’s Home. We visited the nearby national cemetery, and visited the graves of Generals Henry J. Hunt, John A. Logan, and David S. Stanley, and then we had our tour of Lincoln’s cottage. It was a wonderful tour, and, quite coincidentally, guided by an alum of my alma mater, Dickinson College.

From there, it was back to Monocacy to retrieve my camera, and then back to Chambersburg for the annual auction to raise money for battlefield preservation. I donated a tour for four of Brandy Station, Kelly’s Ford, and Trevilian Station. It raised the largest amount of money of the night, which I felt good about.

SATURDAY: On Saturday morning, JD and I had the morning free, so we bummed around Gettysburg for a while. After a lap around the battlefield, we went to the bookstore at the Farnsworth House, where I once again spent too much money. We also went to the Antique Center downtown, and spent even more money on books.

After lunch, with JD’s help, I led a tour of Merritt’s attack on South Cavalry Field, Farnsworth’s Charge, and Fairfield for a group of 7. The group included a woman named Rae Anne McDonald, who is related to Elon J. Farnsworth, which was very cool. It was very hot and somewhat sticky, and I was drenched with sweat by the time we finished the tour. Climbing the hills was a real challenge with my ongoing Achilles tendonitis problem, but I forced myself to do it.

After the tour, we left the group–none of us could bear the thought of yet another tour of the new visitor center at Gettysburg (which I’m not really terribly impressed by anyway), so JD, Jeff Wert, and I traveled to Fairfield to meet Dean and Judy Shultz and our friends Dave and Carol Moore for a fabulous dinner at Dave and Jane’s Crab House. We had several dozen Maryland blue crabs and an amazing meal, and we were all blown away by JD’s session of truly prodigious eating (if I ate the way he does, I would weigh 600 pounds). We got back late, but in time for the final session.

The problem was that there was a bad combination at the hotel: a hillbilly wedding with lots of drunken rednecks and a large batch of mostly unsupervised teenage boys run amok. It made for quite an evening. The hotel, by the way, was a dump. The toilet in my room–probably the second most important thing in a hotel room after the bed–was broken and had to be flushed by taking the lid off the tank and pulling up the flap until it was finally fixed yesterday. Ted got lots of complaints about the hotel, so hopefully, this was the last time it’s going to be used.

SUNDAY: After a leisurely breakfast, we caught the last couple of sessions, followed by a final panel on Stuart in the Gettysburg Campaign featuring J.D., Jeff Wert, and me. It was a good wrap-up to the weekend, and then I hit the road.

I’m glad to be home–if not excited about going back to work tomorrow–and also glad that I’m pretty much done with my conferences for the year–I have only one left, and it’s in November. I’m pretty burned out on them, and I’m definitely burned out on the travel, and just ready to enjoy being home for a while.

Tomorrow, it’s back to normal.

Scridb filterTomorrow at noon, I’m once more on the road, this time to Chambersburg for Ted Alexander’s Mother of All Gettysburg Seminars. On Thursday, JD and I are leading a full day tour of Stuart’s Ride sites. On Friday, we’re going to Washington, D.C. to see sites associated with Jubal Early’s 1864 raid on Washington. Saturday, I’m leading a tour of Farnsworth’s Charge at Gettysburg, and then on Sunday morning, JD, Jeff Wert, and I are doing a panel discussion on Stuart’s role in the Gettysburg Campaign.

This is a real lollapalooza of a Gettysburg program. Historians include, but are not limited to, Ed Bearss, Jeff Wert, Ethan Rafuse, Kent Brown, Joe Bilby, Blake Magner, Rick Sauers, and Dr. Richard Sommers. It’s going to be quite an event. I will have a detailed report on Sunday night when I get home.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like