Author:

We had something close to a perfect storm here yesterday.

Three things converged to create a disastrous windstorm. The combination of a shift in the jet stream, a powerful cold front, and the remnants of Hurricane Ike all came together north and west of Ohio to create a windstorm of absolutely epic proportions. For nearly four hours yesterday, the winds howled like nothing I have ever heard. 75 mile per hour gusts–Category 1 hurricane winds–were recorded at Port Columbus International Airport, which is about five miles from my house. The destruction and devastation is remarkable.

Trees are down everywhere you can imagine. About 500,000 homes in Central Ohio are without power here today, including mine. Virtually all of the schools in the area are closed. There’s no power at my office or at Susan’s. I’m sitting in a hotel room–we came here last night with our dogs–so we would have the basic amenities of life–power, hot water, air conditioning, and Internet access. When I heard it might be several days before power is restored, I elected not to check out of the hotel this morning, figuring it was better to pay for an extra day than to not have the room tonight if our power is not restored today.

Things could have been much worse for us. A limb from my next door neighbor’s oak tree came crashing down, missing my Jeep–parked in the driveway–by three or four inches. They had a tree completely uprooted by the wind. Our neighbors behind us lost about half of a 40-year-old sycamore tree, and a big chunk of it crashed down on their roof. I was out in the backyard when it happened, and I saw it come down and crash.

We lost a tree in our yard. I was outside with the dogs when one of the four main limbs of the tree came off. I had Susan come out to help me because I was trying to keep the thing away from our fence. I was just reaching up to grab the limb when the next one snapped off and came down on top of both of us. I absorbed a lot of the blow when it smacked into my shoulder and neck, but it took Susan to the ground and I had to get her out from under it. We’re both okay. A bit battered and bruised, but okay.

I hope not to ever experience anything like this again so long as I live. It was frightening. I hope all of my readers are okay. For all we experienced, we didn’t have the rain or flooding that they had in Galveston. My thoughts and prayers are with the residents of Galveston and Houston today.

Scridb filterThe closing of the Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington, D.C. has opened up a new opportunity to save a significant portion of the Fort Stevens battlefield. For those unfamiliar with the fight at Fort Stevens, Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Confederate army arrived in Silver Spring, Maryland on July 12, 1864, ready to try to assault the works and then enter the defenses of Washington. The proximity of the Confederate army prompted a response by Grant, who sent the 6th, 19th, and 8th Corps to defend the nation’s capital. Elements of the 6th Corps arrived on July 12, as Early was preparing his assault, and a very significant skirmish, witnessed in person by President Abraham Lincoln, occurred. Early, realizing that the presence of the Federal infantry made it pointless to try an all-out assault on the works, broke off and withdrew back across the Potomac River. It was the only fighting of any consequence to take place in the defenses of Washington, and the only instance where an American president came under fire on the front lines of combat.

Sadly, only a small fragment of the works of Fort Stevens survives, and the overwhelming majority of the battlefield is today a fully-developed urban neighborhood along Georgia Avenue in the District of Columbia. Only the small fragment of Fort Stevens and the Battleground Cemetery, the nation’s smallest national cemetery, survive. Unfortunately, the fragment of Fort Stevens includes a powder magazine that provides an attractive target for the area’s many homeless persons.

Steve Stanley’s fabulous and invaluable map of the battle for Fort Stevens can be found here. This is, without doubt, the best map of the battle for Fort Stevens yet tackled. Be patient–it’s a big file that takes a moment to load. It’s well worth the wait, though.

A significant portion of the Confederate assault on Fort Stevens passed across the grounds of what is today Walter Reed, and there is even a marker on the grounds of the hospital to commemorate the fighting that occurred there. The Civil War Preservation Trust is launching a new campaign to preserve that portion of the Fort Stevens battlefield that lies on the grounds of Walter Reed, and I want to wholeheartedly endorse that effort. Please do whatever you can to encourage the Federal government not to sell the front portion of Walter Reed to commercial developers; help us preserve another fragment of an important Civil War battlefield.

Keep up the good work, guys.

Scridb filterToday marks seven years since the terrorist attacks that changed our world forever. Consequently, I’m going to stray into contemporary events for one day before returning to the normal business of this blog tomorrow.

I’ve already recounted my experiences on 9/11 here, so I won’t bore you with doing so again.

Instead, I want to focus on another issue.

In prior conflicts, it was always easy to define “win”. In the Civil War, for the North, “win” meant putting down the rebellion. In the South, “win” meant separation from the rest of the Union. In World War II, it meant defeating the forces of fascism and removing the militaristic regimes. Even in the Korean War, “win” meant to maintain the sovereignty of South Korea and, under MacArthur, eliminating the Communist regime.

In this Global War on Terror, as it’s called, we don’t have that luxury. People say we have to “win” in Iraq before we can leave. My problem is that I have no idea what that means. What does “win” mean in Iraq? What does it mean in Afghanistan? It seems to me that the definition of “win” is different in Iraq from what it is in Afghanistan. And those who question such things are accused of not being patriotic and not supporting the troops. Senator McCain, for whom I have always had a great deal of respect, can’t define these terms, either.

I don’t want to be overtly political here, but my antipathy for the Bush Administration is no secret. I can’t wait for him to leave office; tomorrow would not be soon enough. In 2004, I said I would have voted for a cinder block if the Democrats had nominated one, and I meant it.

Let’s never forget the sacrifices of the victims of 9/11 and their families. Let’s honor them appropriately, as happened today. I laud both Senator McCain and Senator Obama for setting aside petty partisan politics for one day today and for appearing together in New York. We are, after all, all Americans. At the same time, though, we need to define these terms and understand what it means to “win” this war on terrorism before more tens of billions of dollars are squandered with no real strategy or end game in mind.

Hopefully, our leaders will learn these lessons of history so that their mistakes will not be repeated. Or so I hope.

Scridb filterFrom the September 5 edition of Winchester Star newspaper, it appears that the fight against the mining company is heating up at Cedar Creek. The National Trust for Historic Preservation, unlike the Cedar Creek Battlefield Association, has stepped up to the plate to use the courts to try to prevent the demolition of the battlefield’s viewshed. The Association unfortunately sold its soul for eight lousy acres of marginal land.

National Trust seeks to join quarry litigation

By Erica M. Stocks9-5-2008

Winchester Star (VA)

http://www.winchesterstar.com/Winchester — The National Trust for Historic Preservation is seeking to join 20 local property owners in challenging the Frederick County Board of Supervisors’ decision to allow the expansion of a Middletown quarry.

The trust filed a motion in Frederick County Circuit Court last week asking to intervene as a co-plaintiff in the landowners’ complaint, which questions the supervisors’ approval of a request from O-N Minerals Chemstone to rezone 394 acres to the north and south of its quarry from Rural Areas to Extractive Manufacturing

The rezoning, which will allow the company to mine high-grade limestone from property that it owns, was approved in May.

Opponents of the rezoning, including the National Trust, have argued that the quarry’s expanded operations will threaten nearby historical sites, including the Cedar Creek Civil War battlefield and Belle Grove National Historical Park.

The trust owns Belle Grove, which is open to the public as a 283-acre historical site. The property is within the boundaries of the Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park south of Middletown.

“We have a lot of concerns, not just as a property owner, but as the manager of a historic site open to the public,†Elizabeth Merritt, deputy general counsel for the National Trust, said in a phone interview Thursday.

Twenty people who own adjoining land, or land within 1,500 feet of of the Chemstone property, filed a complaint in Frederick County Circuit Court in June, asking that the court declare the rezoning decision of the Board of Supervisors void because it did not comply with state laws.

“Plaintiffs request that this Honorable Court declare that the zoning decision by the Board was improperly advertised; that it violated the law of Virginia; that the board had no jurisdiction or authority to act on May 28, 2008, on the rezoning; that the rezoning is null and void and of no effect,†the complaint states.

Merritt said the property owners’ complaint raises a number of issues that National Trust officials also think are important.

“We wanted to express our support and make it clear that we are directly supporting them,†she said of the organization’s decision to sign on as a co-plaintiff.

In its motion filed last week, the trust states that the expanded mining operation will consume nearly 400 acres of land on the battlefield property, potentially leading to direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts on the historical park.

“The National Trust, like the existing plaintiffs, seeks a determination by the Court that the rezoning decision is unlawful, and therefore null and void,†the organization states in its motion.

Merritt said the Board of Supervisors specifically failed to provide the type of public access and notice required by the county’s bylaws in approving the rezoning request of O-N Minerals Chemstone, a subsidiary of Carmeuse Lime & Stone based in Belgium. “It raises a number of procedural concerns,†she said.

The property owners’ complaint, as well as the National Trust’s decision to intervene, is in its early stages, Merritt said. “At this point, nothing has really happened.â€

Nord Wennerstrom, director of communications for the trust, said Thursday that the rezoning is not an issue his organization takes lightly.

“Belle Grove has been a historical trust site for 44 years, so it’s important,†he said in a telephone interview.

In June, trust and Belle Grove officials announced that they were ending their involvement with the Cedar Creek Battlefield Association because of the foundation’s failure to fight the quarry expansion.

Belle Grove Inc. said that in April, the foundation reversed its previous opposition to the expansion and arranged with the quarry owner to accept a land gift of eight acres.

Kudos to Belle Grove and the National Trust for taking a stand and in particular for taking a stand against the traitors at the CCBA, who have abdicated the sacred trust entrusted to them.

Scridb filterSusan and I live on the border between the City of Columbus, and its neighboring suburb of Reynoldsburg. Reynoldsburg touts itself as the “Birthplace of the Tomato”, although I’m not entirely sure why. Every year, the city hosts the Tomato Festival, a celebration of everything tomato.

For reasons that are completely lost to me, they’ve included a Civil War encampment this year. What reenactors and tomatoes have in common is really a mystery to me, but somebody has made that connection.

I learned about it at 9:30 tonight, when they started night firing artillery at their encampment, which is less than a mile away. It rattled the windows, scared the living daylights out of Nero and Aurora, who started barking like mad, and caused me and many of my neighbors to stumble outside to make sure that none of the neighborhood houses had blown sky high like that post office in my home town did one night my senior year in high school (which is a whole other story for another time).

Now, I like Civil War re-enactors as much as the next guy. They definitely play a role, and if what they do interests a single kid in the Civil War, then I’m all for them. However, what possible reason is there for firing their guns on a Saturday night in a suburban, densely populated neighborhood? I mean, please……

Scridb filterOn September 1, 1862, the important Battle of Chantilly was fought in Fairfax County, Virginia. The battle was a classic meeting engagement, where Pope’s bedraggled Army of Virginia and Stonewall Jackson’s command tangled in a blinding rainstorm. Two important Union generals, Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny and Maj. Gen. Isaac Stevens, were killed in the confused fighting that day. Unfortunately, the bulk of the battlefield was lost to commercial development in the 1980’s, and only a small fragment of the battlefield, featuring twin monuments to Kearny and Stevens, was saved. Our friend Paul Taylor has written an excellent book about the Battle of Chantilly that I commend to you.

Only one good thing came out of the loss of the Chantilly battlefield. Three dedicated locals, Clark B. “Bud” Hall, Ed Wenzel, and Brian C. Pohanka, were outraged by the loss of the battlefield, and they decided to do something about it. Consequently, they formed the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites (“APCWS”). About ten years ago, APCWS was merged into a similar organization, the Civil War Trust, to form the Civil War Preservation Trust, which does great work saving battlefield land around the country. So, but for the loss of most of the battlefield, we might not have the CWPT to do such a great job.

In any event, Ed Wenzel has remained dedicated to the preservation and marking of the battlefield at Chantilly, and after a lot of work, his efforts have finally paid some dividends. On Monday of this week, the 146th anniversary of the battle, a ceremony was held. From the Washington Times newspaper:

Ox Hill battlefield saved by locals

Restored site to be dedicated on fight’s 146th anniversaryMartha M. Boltz SPECIAL TO THE WASHINGTON TIMES

Thursday, August 28, 2008The Battle of Ox Hill on Sept. 1, 1862, the only battle fought in Virginia’s most populous county, has been virtually ignored for years.

That will end at 10 a.m. Monday, when the Fairfax County Park Authority dedicates a newly restored park 146 years to the day since about 15,000 soldiers met at a battleground called Ox Hill by Confederates and Chantilly by the Union. It has been a long time coming.

Many historians and preservationists thought the battlefield was important enough to save because it was the site of one of Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s independent actions just after the Battle of Second Manassas, the main thrust of which was to prevent Gen. John Pope’s retreating Union army from reaching the defense line of Washington.

The somewhat demoralized Confederate army, which had marched 10 miles in eight hours the previous day, could not accomplish its objective – but about 1,100 Rebels were lost before that became apparent. At the same time, the Union lost two seasoned leaders, Gens. Philip Kearny and Isaac Stevens.

Death in the rain

The battle began in the afternoon and did not end until dark. It was the scene of massive thunderstorms – lightning strikes and rolling thunder that almost overshadowed the rifle fire.

The rains that Monday were so heavy that the order was given to use sabers instead of rifles because the rain had made the paper cartridges unusable. When one officer sent a message to Jackson asking that his regiment be taken out of line because of his troops’ wet cartridges, Jackson’s acerbic reply was that he was sure the enemy’s ammunition was just as wet.

Kearny’s death came partially because of his own impulsivity. He was confident there were no Confederates in the immediate area, but after receiving a message from Gen. David B. Birney that there was a gap in the Union line, he rode furiously through a cornfield to reconnoiter. He rode directly into a line of Rebels, realized his error and tried to escape. At the same time, some of the Southern troops shouted, “That’s a Yankee officer! Shoot him!”

The order to halt was sounded. It was ignored, and a dozen muskets rang out. It was all over for Kearny. The 49th Georgia regiment is credited with the shot that killed him.

It was about 150 yards from two present-day granite monuments, in a cornfield. Kearny had come into the battle with a handicap, which did not lessen his abilities: During the Battle of Churubusco in the Mexican War, his left arm had been amputated as the result of wounds.

Stevens, another West Point graduate, entered the Union Army as colonel of the 79th New York Highlanders, later called the Cameron Highlanders. Fort Stevens on the outskirts of Washington is named for him. He was made a brigadier general on Sept. 28, 1861, and fought at Port Royal, S.C. He was transferred with his IX Corps to Virginia to serve under Pope and took part in the Northern Virginia campaign and Second Manassas.

His rather picturesque death came after he picked up the fallen colors of his old regiment and shouted, “Highlanders, my Highlanders, follow your general!” He was struck in the head by a bullet and died instantly with the colors still in his hand while leading the charge against Confederates massed in the woods (near present-day Fairfax Towne Center).

The Union sustained a great loss from these two deaths alone.

Flag of truce

Finally, as darkness closed in, the fighting had almost ended. With wet musket cartridges, the battle had disintegrated into one of clubs and bayonets. About that time, troops arrived in the area to support Jackson and his weary men.

For all intents and purposes, the battle was over; the Union forces were withdrawing to the Warrenton Pike with some of their wounded, coming on to Fairfax and Alexandria.

Kearny’s body was sent back to the Federal lines under a flag of truce. The ambulance bearing the body was escorted down the turnpike by Maj. Walter Taylor of Gen. Robert E. Lee´s staff and five or six men and delivered to pickets of the 9th New York Cavalry at Difficult Run. That site today is at the Route 50 and Interstate 66 interchange, according to Ed Wenzel, a local preservationist.

Lee’s men may have been in control of the battlefield, but the battle would go down in history as a draw, with tactical advantage to the Southerners. In the following days, Confederate and Union forces would clash again at Dranesville and then Leesburg, which set the stage for the Maryland Campaign. That would lead to the final and bloodiest battle of them all, Sharpsburg (or Antietam), on Sept. 17.

Still, Ox Hill was an important fight, and the little battlefield deserved more recognition than a brown sign and the historical marker erected in 2000.

Saving the field

As encroaching development threatened to eradicate the battlefield, a group of preservationists and historians intervened. In 1986, Mr. Wenzel, a local resident, spotted bulldozers and graders at work near the site. His warning led to the formation of the Chantilly Battlefield Association, Chantilly being the name of a nearby mansion and the name favored by Union troops. Confederates called it Ox Hill because of a 503-foot rise.

When plans were unveiled recently to move the granite markers for the two generals as well as a memorial pile of boulders, the Chantilly Battlefield Association redoubled its efforts to find a way to preserve the site.

Shopping centers and malls, high-rise office buildings, town houses and four-lane highways came closer and closer to the relatively small combat area left undeveloped from the 500 acres the battlefield originally comprised.

The remains of a Confederate soldier were found during the construction of nearby town houses as late as 1985. Uniform buttons identified him as being from South Carolina, and authorities there came to reclaim the body for burial in his home state.

To save what remained of the battlefield, a determined band of preservationists swung into action, including Mr. Wenzel, Clark B. Hall, Brian Pohanka and members of the Bull Run Civil War Round Table, who had formed the Chantilly Battlefield Association.

Mr. Pohanka’s words, spoken several years before his death in 2005, became the mantra of all: “Some kid a hundred years from now is going to get interested in the Civil War and want to see these places. He’s going to go down there and be standing in a parking lot. I’m fighting for that kid.” His widow, Cricket Pohanka, serves on the CBA in his place.

A compromise

Builders and developers have deeper pockets than preservationists or park authorities, and it was a one-sided battle, with ideas for additional construction along Route 50 being considered and the CBA laying plans to block it.

A compromise finally was reached, resulting in 4.8 acres of Fairfax County parkland. It is not enough – it never is. Some say the battlefield has been destroyed – that with just 1.4 percent of the core combat area protected, the result is minuscule. Some opine that people can’t interpret a battle from a postage-stamp park. Yet an effort is being made to do just that.

The memorial markers for Stevens and Kearny are the biggest attraction. They were erected in 1915 by the Ballard family, which owned the farmland at the time, and the nearby pile of boulders was left to the memory of the two men, both of whom are buried elsewhere.

John Ballard was a former Confederate cavalryman who had ridden with Mosby’s Rangers and had lost a leg in 1863. He married Mary Reid Thrift, the young heiress to the farm where the battle was fought. There they raised their family and farmed the land.

In 1883, Charles Walcott, formerly of the 21st Massachusetts, and Hazard Stevens, who was wounded at Ox Hill and was the son of Isaac Stevens, returned to the battlefield to retrace their steps and find the places where the two generals had fallen. They visited the Ballards, enjoyed their hospitality and walked the fields, identifying the spots where Stevens and Kearny were killed.

Ballard later marked the place where Stevens died with a white quartz boulder and other rocks. Years passed, and in 1915, John and Mary Ballard deeded a 50-by-100-foot lot at the site of Stevens’ death to three trustees from New Jersey (the 1st New Jersey Brigade Society) and three from Virginia for the placement of monuments or markers.

Subsequently, two monuments, one for Kearny and one for Stevens, were dedicated at a ceremony attended by dignitaries, local people, Union and Confederate veterans and the children and grandchildren of the two generals. The monuments were surrounded by a small wrought-iron fence. That ultimately would be the only protected area on the entire battlefield, handed down through generations.

The price tag

A large concrete marker, called Kearny’s Stump, also was left intact. It replaced the original tree stump, which had rotted away, and bears his name and a large cross. The pile of boulders was preserved by the park authority, to the extent of being covered over with dirt and a tarp to prevent its harm or destruction, and will become part of the park.

Ultimately the park authority reached an agreement with Centennial Construction Co. to leave the boulders where they were and to donate 2.4 acres to the county for a battlefield park. The Fairfax County Park Authority agreed to match the acreage. Costs to complete the park are estimated at about $400,000, of which the authority has just $274,000 budgeted. Public fundraising will be essential to complete the park, and the CBA remains optimistic it will be found.

The park contains a hiking trail, interpretive exhibits and three hexagonal information kiosks that tell the story of the battle and its significance to the war in Virginia. The visitor will step into a portion of the original cornfield, within two reconstructed split-rail fences that follow the actual fence lines of the fields. The adjacent cornfield will be planted with grasses that will give the impression of corn, as the latter is deemed too labor-intensive to be used.

A celebration

Mr. Wenzel worked closely with the park authority each step of the way, and he praises the master plan.

“To a great extent, the planning and work has resulted in an undulating landscape,” Mr. Wenzel said, “and the topography rises and falls across the fields, giving the battlefield a realism that is not apparent on a flat map.”

The new park comes with a wheelchair-ready trail surfaced with paving blocks, compliments of the regulatory process. So much for 1862 and the historic landscape – though the more urban and unsteady among us might welcome the trail.

In truth, the attractive pavers, even when surrounded by pea gravel, make walking on them difficult even with the lowest of women’s heels. Some also think the large concrete park benches are a contemporary distraction. The hexagonal information kiosks endeavor to match the color theme of the war, the gray (Confederate) sides or columns being topped with blue (Union) roofs.

Finally, 14 years after the last parcel of land from the battlefield was acquired, the Fairfax County Park Authority is ready to dedicate the new park.

Public information officer Judith Pedersen, who played a large role in the project, said of the dedication ceremony to be held Monday: “We want it to be a celebration – it would not be here if it were not for the true passion and dedication of those who care about the history and heritage found here.”

She learned firsthand of the depth of their devotion at the groundbreaking ceremony some time ago.

“It began to rain,” she said, “and it kept on raining. I couldn’t help but think that that’s the way it was back in 1862 with the storms. I kept thinking we might have to abbreviate the ceremony, leave something out, but all the participants stayed. They all had thoughts to share and knew how important the day was. I knew then I was talking with dedicated people.”

Miss Pedersen added, “It’s very unusual for us to do anything regarding cultural resources in a park. Our main thrust is recreational, and we don´t have much experience in the cultural, but this has been a wonderful project. I can’t wait for it to be open and ready for use.”

Future monuments

Another Park Authority employee, Michael Rierson, emphasized that the interpretive signs and panels will help casual visitors as well as Civil War enthusiasts to better grasp the importance of Ox Hill.

While acknowledging that he and others wish more of the battlefield could have been preserved – it runs from Fair Oaks Mall all the way to Fair Lakes – Mr. Rierson added: “Even though we did not save more of the original battlefield, it will be a great little park site.”

Plans call for a fundraising drive to erect two large granite monuments to honor the contribution of the common soldier because only the two slain officers are recognized and no attention is given to the Confederate troops who fought and died there. The Union monument will carry the name of Chantilly and the Confederate one Ox Hill.

To paraphrase the title of a famous children’s book, the little battlefield that could finally did. It survives, in large part, thanks to a group of determined local residents who would not give up the fight and to a park authority that seized the opportunity to work with them.

Somewhere up in heaven, Mr. Pohanka is raising his arm in the air and saying, “Yes!”

cMartha Boltz is a frequent contributor to the history page. She thanks Ed Wenzel for sharing his research.

I suspect that Martha is right about Brian Pohanka. Nice work, gentlemen. A little bit of the battlefield is better than none at all.

Scridb filterOur friend, Ranger Mannie Gentile, has THE coolest blog post ever on his blog this weekend. If you’ve ever wondered about the fight for the Sunken Road at Antietam, I guarantee you that Mannie’s post will answer those questions forever.

Check it out.

Scridb filterMike Block of the Brandy Station Foundation passed this item from the Shreveport Times newspaper along:

Louisianans headed to Poland to honor cavalry officer

Heros Von Borcke was a larger-than-life figure.BY JOHN ANDREW PRIME JPRIME@GANNETT.COM AUGUST 25, 2008

In a tribute to diversity, two Louisianans are headed to Poland to honor a Prussian aristocrat who fought for the Confederacy almost 150 years ago.

Chuck Rand, of Monroe, and Michael Bergeron, of Baton Rouge and Lake Charles, are en route to Eastern Europe to help dedicate a new U.S.-supplied military gravestone for Col. Johann August Heinrich Heros von Borcke, a soldier who served with the South in the 1860s and became a heroic figure among its cavalry corps. A 6-foot 4-inch prankster who fought with enthusiasm, and who almost could have been taken from an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie, his wounding in 1863 just before the Battle of Gettysburg is thought by some historians to have changed the course of the conflict.

“It is interesting that events that occurred in North America over 140 years ago not only still reverberate here but also have echoes in Europe,” said Rand, who is the national chief of staff for the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Heros von Borcke is due his tombstone through a change in U.S. law that has recognized Confederate veterans as U.S. soldiers since the early 1900s.

While the government provides tombstones for former Confederates, they are different in design from traditional gravestones for other U.S. soldiers in that they have a pointed, rather than a rounded top.

The gravestone dedication and graveside memorial service, which will be open to the public and the media, will begin at 10:30 a.m. in Gyzin, also called Giessenbrugge.

Due to wars and boundary changes in Europe, the historic residence of the Von Borcke family was once in Prussia, a part of old Germany, but now is in modern Poland.

Von Borcke’s original tombstone was destroyed by the Soviets after they occupied the region following World War II.

Rand and Bergeron will represent the Sons of Confederate Veterans at the event.

The national heritage group has another Louisiana connection through its national commander in chief, Shreveport Charles McMichael. Rand and Bergeron will present the Von Borcke Family with a certificate from McMichael noting their ancestor’s service.

Von Borcke was an imposing presence in the Confederacy, as he was a top aide and confidante to James Ewell Brown Stuart, the famous cavalry leader.

A signal character in the June 9, 1863, battle of Brandy Station, the largest cavalry encounter of the war, he was known to give advice and guidance to Stuart.

But Von Borcke was badly wounded in the neck at the Battle of Middlesburg 10 days later. Stuart and his cavalry were absent from the July 2-4 Gettysburg battle at crucial times, and some historians believe that had Von Borcke been at Stuart’s side, he might have given Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia better service when most needed.

“Upon returning to Germany, Col. Von Borcke wrote a book titled ‘Memoirs of the Confederate War for Independence,'” Rand said.

Von Borcke, who died in 1895 at the age of 60, flew the Confederate flag from the battlements at his ancestral castle and even named his daughter Virginia in tribute to his service.

The U.S. War Between the States is a topic of interest in Europe and other parts of the world, with re-enactors active in Germany, Poland, Australia and South America.

In addition to the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a company of German Confederate reenactors, Hampton’s Legion from Berlin, will fire a salute in honor of Von Bocke, with attendees from units in Germany, Sweden, Spain, Switzerland, Italy and other countries looking on.

von Borcke was a fine soldier who left his mark on the Confederate cavalry. When he was wounded at the June 21, 1863 Battle of Upperville, Stuart, his best friend, was greatly worried for his friend’s safety.

I am very pleased that von Borcke is finally having his grave marked again, and that his service in the Civil War is being honored.

Scridb filterSince I’ve profiled a Union cavalry officer who was an alumnus of Dickinson College, fairness requires that I similarly profile a Confederate Dickinsonian.

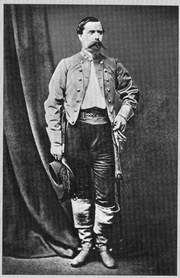

Richard Lee Turberville Beale was born into a prominent Virginia family on May 22, 1819. Young Beale attended private schools in Westmoreland County, Northumberland Academy and Rappahannock Academy, Virginia. He enrolled in Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with the class of 1838 and was elected to the Union Philosophical Society. He later left Dickinson and then completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Virginia in 1837. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and opened a private a practice in his hometown of Hague.

Richard Lee Turberville Beale was born into a prominent Virginia family on May 22, 1819. Young Beale attended private schools in Westmoreland County, Northumberland Academy and Rappahannock Academy, Virginia. He enrolled in Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with the class of 1838 and was elected to the Union Philosophical Society. He later left Dickinson and then completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Virginia in 1837. He was admitted to the bar in 1839 and opened a private a practice in his hometown of Hague.

Beale also entered politics. Active in the Democratic Party, he was elected to a serve in the Thirtieth United States Congress in 1847, was a member of the 1851 Virginia constitutional convention, and served as a Virginia state senator from 1858 to 1860. He was married to the former Lucy Brown, and had several children.

Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War, in May, 1861, he was commissioned a lieutenant of cavalry in Lee’s Light Horse, a provisional unit which was later organized into the 9th Varginia Cavalry, known as “Lee’s Legion.” The unit was named for its first colonel, William H.F. Lee, the second son of Robert E. Lee. He was soon promoted captain and then major, was put in command at Camp Lee, near Hague, on the lower Potomac, where his intelligence and excellent judgment were of much value. Beale had achieved the rank of major by October 1861.

In 1862, he was named lieutenant colonel of the 9th Virginia. When Lee was promoted to colonel in the fall of 1862, Beale was promoted to colonel of the 9th Virginia. In December, 1862, he attracted attention and much favorable comment by a bold expedition into Rappahannock county, in which the Federal garrison at Leeds was captured, without loss. He served in all the cavalry battles of the Army of Northern Virginia including Fredericksburg. On April 16, 1863, he won the praise of J. E. B. Stuart for his heroic service in meeting and repelling the threatened raid of Stoneman’s cavalry division, and during the renewed movement by Stoneman at the close of the month, he was for a week in almost constant fighting, his regiment everywhere behaving valorously and capturing many prisoners. At the Battle of Brandy Station, he led the 9th in a brilliant charge in which Gen. W. H. F. Lee was wounded and Col. Solomon Williams of the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry was killed.

Beale also played a significant role in Jeb Stuart’s ride during the Gettysburg Campaign. Late in life, when he wrote a history of the 9th Virginia Cavalry, he recalled with affection seeing his alma mater during J.E.B. Stuart’s brief occupation of Carlisle on July 1-2, 1863. His son George W. Beale served as an officer in the regiment.

He was wounded in a skirmish at Culpeper Court House on September 13, 1863 and spent three months on convalescent leave. He returned to duty in January 1864, assuming command of his brigade and was eventually named a brigadier general. In March, 1864, having been stationed on the Northern Neck, he made a forced march to intercept Col. Ulric Dahlgren and his Union raiders, and a detachment of his regiment under First Lieut. James Pollard, Company H, successfully ambushed the Federals. Pollard, aided by other detachments, captured about 175 men and killed Dahlgren. The papers found upon Dahlgren’s person, revealing a design to burn Richmond and kill President Davis and cabinet, were forwarded by Colonel Beale, through Fitz Lee, to the government. A correspondence with the Federal authorities followed, in which they disavowed all knowledge of such a design. He participated in command of his regiment in the campaign from the Rapidan to the James, was distinguished in the fighting at Stony Creek, and toward Reams’ Station, in July, capturing two Federal standards; and in August, upon the death of Gen. John R. Chambliss, Jr., was given command of Chambliss’s brigade. February 6, 1865, he was promoted to brigadier general, and in this rank he served during the remainder of the struggle. Official confirmation of his rank came in January, 1865.

Ironically, Beale was a reluctant soldier who chafed against the pettiness and administration of regular army life and who regularly threatened resignation. He offered once to command guerillas or even revert to the rank of private. His superiors always persuaded him to remain at his post. By the end of the war, he had become an outstanding commander of cavalry.

Following the war he went home to Hague, Virginia to practice law and involving himself in editing and local politics. He decided to run for Congress again and was elected as a Democrat to finish the term of fellow Virginia cavalryman, Beverly B. Douglas, who had died in office. He was reelected to a full term in the next Congress and served from 1879 to 1881. After leaving Congress again, he returned to his practice and the writing of a history of the Ninth Virginia, which was posthumously published by his son George.

Richard Lee Turberville Beale died in Westmoreland County on April 18, 1893 and was buried in the family plot at Hickory Hill. He was seventy-three years old.

Here’s to forgotten Confederate cavalry and Dickinson College alum Richard L. T. Beale.

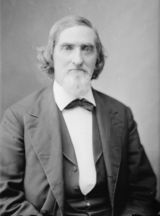

Scridb filterToday, I am going to profile a forgotten cavalryman named Bvt. Brig. Gen. Thomas Jefferson Jordan, who, like me, was an alumnus of Dickinson College, one of a number of notable cavalry officers who graduated from Dickinson.

Thomas Jefferson Jordan was born in December 3rd, 1821, to Benjamin Jordan and Mary Crouch on the family farm, Walnut Hill, in Paxtang, Dauphin County Pennsylvania. The family was of Scottish origin and came to this country in 1720, first settling in King and Queen County, Virginia. In 1742, his great-grandfather, James, left Virginia, and with his slaves came to Pennsylvania, where he bought a large tract of land on the Susquehanna River, near Wrightsville, York county. His grandfather, Thomas Jordan, was born in Cecil County, Maryland, and married Ann Steele, daughter of Capt. William Steele of Drumore, Lancaster County, PA and widow of Robert Dickson.

Benjamin Jordan was born near Milton, PA in 1779 shortly before the family fled due to Indian attacks. They later lived in Hopewell, York County, PA. During the war of the Revolution the grandfather was a paymaster with the rank of Major, and served as such during the entire war. The father married Molly, the only daughter of Edward Crouch, a Captain in the Revolutionary army, she being a granddaughter of General James Potter, of Pennsvalley, also a soldier of the Revolution. Jordan was paymster for General Potter in the Pennsylvania militia and fought with Potter in Chester County, PA.

Benjamin Jordan’s mother had three brothers that eventually became generals in the Revolution and War of 1812. His aunt, Rachel Steele, married Jacob Bailey, brother of Francis Bailey, and the Baileys and Steeles were involved in the printing trade for multiple generations with Francis Bailey printing newspapers, almanacs and becoming the official printer for Continental Congress, and a close friend of Benjamin Franklin and witness to Franklin’s will. Benjamin’s half brothers, William and Robert Dickson, were associated with the Lancaster Intelligencer and Benjamin had apprenticed there as a young man before going on to a career in politics . He was a friend of Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s first Secretary of War and was also an investor in the Bank of Middleton with Cameron.

Thomas Jefferson Jordan spent first fourteen years of his life in the local country school, along with the other farmers’ boys, remaining enrolled there until in the summer of 1839. In December, 1839, he enrolled in the Law Department at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, then under the leadership of its founder, Judge John Reed. He attended the College for the following two years and in February, 1843 was called to the Dauphin County bar in Harrisburg and opened a practice.

He practiced law and ran a lumber business in Harrisburg until the Civil War broke out. On April 17, 1861, the day after Fort Sumter fell, Jordan was commissioned as aide to Maj. Gen. William Hugh Keim, who was raising volunteers in Pennsylvania. He served Keim well. Jordan carried the first news of the riots in Baltimore to Bvt. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, and then commanded a brigade in the Shenandoah Valley. Jordan first saw action with Keim at Falling Waters in early July 1861, gaining valuable experience against the Virginia forces of Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston.

At the end of that campaign, Jordan was mustered out and received a new commission as a major. He was ordered to assist Col. Edward C. Williams in the recruiting and organization of a cavalry unit that became the Ninth Pennsylvania Cavalry in October 1861. This regiment was also known as the “Lochiel Cavalry” and as the 92nd Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers.

With Jordan commanding its Third Battalion, the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry was deployed to the Cumberland Valley and then was sent west to the column commanded by General Don Carlos Buell, then at Louisville, Kentucky, where it arrived in November, 1861. The regiment saw action in Kentucky and Tennessee in early 1862. At Tompkinsville, Kentucky, on July 9, 1862, a superior force of Confederate raiders under command of the dashing Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan surprised Jordan and three companies of the Third Battalion. Jordan organized a fighting retreat but elements of the rearguard and the major himself were captured by Morgan. He was sent to the Confederate POW camp at Madison, Georgia, and was later transferred to Richmond’s Libby Prison.

Once a prisoner of war, Jordan came under attack for alleged ill-treatment of civilians in Sparta, Tennessee the previous May and was moved from Libby Prison to Castle Thunder Prison to face charges. However, a subsequent investigation determined that his unit had only been in Sparta for a few hours and that the charges were based on Jordan’s demand to the women of the town quickly to prepare a meal for his men. He was exonerated and subsequently exchanged in December 1862.

Jordan returned to his regiment in January 1863. In the meantime the Colonel had resigned, and the Lieutenant Colonel was terminally ill. Jordan was, accordingly, appointed Colonel. At Shelbyville, Tennessee, on June 9, 1863, he led the charge on the left, a most gallant action, which scattered the enemy and put him to inglorious flight. At Thompson’s Station, when Colonel Coburn of an Indiana regiment had tamely surrendered, he brought off the surviving forces, saving the artillery and baggage, and fighting heroically against a force of 5000 cavalry, led by Nathan Bedford Forrest. At the moment when General Bragg’s army was retiring across the Cumberland mountains at Cowan, Tennessee, Colonel Jordan and his command charged and captured over five hundred prisoners.

In the Battle of Chickamauga, when ruin was impending on other parts of the field, he heroically defended the right of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, enabling that gallant soldier to stem the tide of disaster. His conduct so impressed Thomas that he asked President Lincoln to promote Jordan in recognition of his meritorious service at Chickamauga.

He fought and defeated Brig. Gen. George Dibbrell’s cavalry at Reedyville, though the latter was at the head of a force of 2500 men. He was active in the campaign against Longstreet in East Tennessee in the winter and spring of 1863-64, and fought in the battles of Mossy Creek, Dandridge and Fairgarden. In the battles of Lafayette, Dalton, Kenesaw, Big Shanty, Resaca, New Hope Church, Peach Tree Creek, and in front of Atlanta, Colonel Jordan was constantly engaged. When the enemy finally retreated, he followed close upon the trail and was sharply engaged with Wheeler’s troopers at Jonesborough and Lovejoy’s Station.

He was placed in command of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the cavalry in the March to the Sea, with which he met Wheeler at Lovejoy’s Station, and after a sharp engagement routed him and captured all his artillery, retaining the pieces which were of superior quality in his command until the end of the war. He again defeated Wheeler at Waynesburg, Georgia, where he led his brigade in a charge upon the enemy’s position, and ended the fight before the reserves, sent to his relief, could arrive. He first invested Fort McAllister near Savannah, driving the rebels within their works, and was only prevented from carrying them by assault by the arrival of General William B. Hazen, with his division of infantry, who superseded him in command.

On the march through the Carolinas Colonel Jordan crossed the Savannah River in advance of the infantry at Sister’s Ferry, and covered the Left Wing of Sherman’s army under command of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum. His position in the column on the march north was such that he was brought often to severe conflict. He led the charge at Blackville, dislodging the enemy from the town. He held the position at Lexington, protecting the flank of the infantry, while Columbia was being occupied. With Wheeler and Hampton he had a stubborn action at Lancaster, and crossing into North Carolina led the advance to Fayetteville, daily and hourly skirmishing heavily.

The Battle of Averasboro, fought on March 16, 1865, opened early in the day. Jordan’s brigade fought unaided until two in the afternoon, when the infantry of the Twentieth Corps came to his assistance. In this action, every twelfth man in his entire force was either killed or wounded. At Bentonville, he held the left flank, and participated in all the movements of the day. In the advance against Raleigh he again had the lead, and entered the city on the morning of April 12th, 1865. On passing through, he found that the rebel cavalry was ready for action on the Hillsborough road, and at once moved forward to the attack, driving them before him the entire day. At Morristown he was met by a flag of truce, with a letter for General Sherman from General Joseph E. Johnston, proposing to surrender, when fighting ceased. Jordan was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers for his long and meritorious service in February 1865. The 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and Jordan with it, was mustered out on July 18, 1865.

He had married before the war and he corresponded extensively with his wife, Jane, during the war. After the war, he briefly returned to the legal profession in Harrisburg. A few years later, he went into the lumber business in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, but the business eventually failed. Perhaps due to his advanced age, he secured a position with the U. S. Post Office and then transferred to the U. S. Mint in Philadelphia. He died in Philadelphia on April 2, 1895 and was buried in Section 11, Lot 19 of the Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware. He was seventy-four years old.

Jordan was an able field commander who was well thought of by his superiors and respected by his men. Except during his time as a POW, he was constantly in the field with the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, in spite of bad health that often compelled him to accompany his command in an ambulance.

Here’s to forgotten cavalryman and Dickinson College alum, Bvt. Brig. Gen. Thomas Jefferson Jordan.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like