Author:

I was given the privilege of having the first interview with Stephen M. “Sam” Hood about a remarkable find that Sam made pertaining to his ancestor, Gen. John Bell Hood.

I was given the privilege of having the first interview with Stephen M. “Sam” Hood about a remarkable find that Sam made pertaining to his ancestor, Gen. John Bell Hood.

Sam Hood is a graduate of Kentucky Military Institute, Marshall University (bachelor of arts, 1976), and a veteran of the United States Marine Corps. A collateral descendent of General John Bell Hood, Sam is a retired industrial construction company owner, past member of the Board of Directors of the Blue Gray Education Society of Chatham, Virginia, and is a past president of the Board of Directors of Confederate Memorial Hall Museum in New Orleans. Sam resides in his hometown of Huntington, West Virginia and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina with his wife of thirty-five years, Martha, and is the proud father of two sons: Derek Hood of Lexington, Kentucky, and Taylor Hood of Barboursville, West Virginia.

Question: I understand that you are related to General Hood. How are you related to him?

I am a second cousin. I descend directly from his grandfather Lucas Hood, who was my great x 5 grandfather.

Question: When was this set of papers of General Hood’s discovered?

Well actually, they weren’t so much “discovered” as “realized.” I was invited to the home of a direct descendent in June to look through what was thought to be just boxes of routine family papers and memorabilia that had been passed down and accumulated through the decades. The descendent knew I was finishing my book and thought that maybe…just maybe…there might be something in the boxes that I could use in my manuscript.

Question: What did you do when you discovered the collection?

I was utterly stunned. The family had set me up in a vacant bedroom of their home to use as an office, and brought out 3 or 4 bankers boxes, and invited me to call for them if I needed any assistance.

Question: What was your reaction when you learned of the existence of this collection of papers?

After a few minutes with the collection, my priorities immediately changed. When I saw the incredible historical importance of many of the documents my top priority changed from seeking interesting information to helping them identify and secure the documents, which was done. The task actually took two trips of 3 days each, with my wife Martha accompanying me and assisting me on the second trip. The valuable papers were identified, placed in acid-proof folders, and physically removed to the owners’ bank safety deposit box. I made photocopies of everything to take home, where I began the process of transcribing the letters. It wasn’t until then that I started finding the historically important content of the letters.

Question: Without being too specific, as I know that you want to maintain some semblance of confidentiality regarding the specific contents, can you give our readers an idea of what’s in the collection?

Approximately 80 letters to Hood by high and lower ranked Civil War characters, Union and Confederate, wartime and postwar. Correspondents include Jefferson Davis, Robert E Lee, SD Lee, Braxton Bragg, James Seddon, AP Stewart, WH Jackson, SG French, William Bate, Henry Clayton, FA Shoup, Mrs Leonidas Polk, William M Polk, WS Featherston, Stonewall Jackson, James Longstreet, David S Terry, Matthew C Butler, GW Smith, PGT Beauregard, Louis T Wigfall, George Thomas, WT Sherman, and numerous lower ranked officers, mostly members of commanders’ staffs. There are 61 postwar letters from Hood to his wife Anna, and 35 from Anna to him as he traveled in his insurance business. Also included are Dr John T Darby’s two highly detailed medical reports of Hood’s Gettysburg and Chickamauga wounds, and the daily log of Hood’s treatment and recovery from the day of his leg amputation until November 24 in Richmond. The collection also includes Hood’s Orders and Dispatches log and 4 volumes of Telegram logs for his entire tenure as commander of the Army of Tennessee. Additionally, Hood’s first and second lieutenant’s commission certificates from the US Army are in the collection, along with 4 remarkable documents: his original commission certificates for his ranks of brigadier general, major general, lieutenant general, and full general in the Confederate Army. There are also numerous photographs and other ephemera of Hood, his children, and his grandchildren.

Question: In your opinion, what is the significance of this collection?

You should probably ask credentialed scholars this question, but I can’t imagine a discovery of Civil War documents being more profound than these.

Question: In your opinion, how does the unearthing of this collection change or impact the impression that the public has of John Bell Hood and his legacy to the American Civil War?

There are a few specific items that are quite profound. Letters from three separate officers identify Hood’s subordinate who was responsible for the Confederate failure at Spring Hill. A senior commander explains Patrick Cleburne’s behavior before and during the Battle of Franklin–characterized in modern Civil War scholarship as being peculiar–and it had absolutely nothing to do with General Hood. In one letter SD Lee makes some very serious charges against William Bate at the Battle of Franklin.

A letter sheds new light on the nature and intent of Hood’s correspondence with Richmond authorities in the spring of 1864, characterized by Hood’s critics as “poison pen” letters intended to undermine Joseph Johnston. Several letters back up claims that Hood made in his memoirs concerning controversies with Johnston, including the Cassville Affair, and Johnston’s heavy losses during the Atlanta Campaign, mostly due to desertions.

Dr Darby’s medical reports are fascinating, and include detailed daily records of the medications prescribed to Hood.

There is much more important historical information, although not so controversial.

Question: What are your intentions for the collection?

I have none. The owners, who insist on complete anonymity at this time, intend to retain all the original documents as treasured family artifacts. However, copies of all the documents will be released to a yet-to-be-determined public repository at some time in the future. I have begun work on an annotated book of the papers, which I hope to complete by next spring for publication next fall (2013.) Since the papers will be cited, copies will have to be made public at that time if not sooner.

Question: Have you used these newly-discovered documents in your forthcoming book, John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General?

Yes. I was able to transcribe many, but not all of the letters, and none of the orders and dispatches or telegram logs. I was able to include much of the important information in my forthcoming book, John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General (Savas Beatie Publishing, Spring 2013.) (It was originally to be titled History versus John Bell Hood but the publisher felt the new information justified the new title.)

Question: What would you like for the readers to know about your book?

Thanks for asking this question, Eric. Even without the newfound information I have always felt that available historical records disprove many of the outlandish charges that have been made against JB Hood in modern Civil War literature. Authors like Wiley Sword have cherry picked the records, filtering out of their books all evidence and testimony that doesn’t paint Hood as an incompetent scoundrel. My book reveals to readers, as the late Paul Harvey used to say, “The rest of the story.” Also, the paraphrasing used by critical authors is often remarkably misleading, and in many cases the exaggeration and hyperbole completely distorts the accurate context. My book is 100,000 words of examples of concealment of historical evidence and distortions, but it could have been 200,000 words long.

The newfound information just reinforces what the available historical records reveal about JB Hood had authors not had an agenda.

Eric: Thanks to Sam Hood for granting me this interview, and thanks to Sam for sharing this vital information with me.

My opinion is that this is, perhaps, THE most important find in my lifetime. This treasure trove of letters has the potential to dramatically change how history perceives John Bell Hood, and it certainly will help to change how history remembers Hood. This is certainly an exciting find, and I’m pleased that Sam chose to share these insights with me.

Scridb filter From the gift that keeps on giving–the incompetent board of appeasers of the Brandy Station Foundation–we have this delightful little tidbit.

From the gift that keeps on giving–the incompetent board of appeasers of the Brandy Station Foundation–we have this delightful little tidbit.

You can’t make this stuff up, folks.

From Sunday’s edition of the Culpeper Star-Exponent:

By: Vincent Vala | Culpeper Star Exponent

Published: October 28, 2012

» 0 Comments | Post a Comment

The Halloween spirit visited Brandy Station this weekend as the Brandy Station Foundation offered up its annual “Spirits of the Graffiti House” event at the historic facility off U.S. 29 North Saturday evening.Between 6 and 9 p.m., the former Civil War hospital facility was open to the public for tours, treats and tales of the unnatural that have been reported at the Graffiti House over the years.

Visitors could mix history, All Hallows Eve and having fun, all it the good spirit of the harvest season.

“We kind of combine a lot of different things for the evening,” said Helen Geisler, a member of the BSF board of directors. “It’s just intended as a fun evening for the children – and for the adults.”

Geisler said this is the fifth year for the event.

“Last year, we had well over 100 people turn out,” she said. “So this year we’ve prepared for at least that many.”

Throughout Saturday evening, tour guides talked to visitors about the graffiti in the upstairs rooms of the house, while Transcend Paranormal Investigators gave talks in a downstairs room.

A video produced by the R.I.P. Files about their overnight stay in the house was played in the house’s entry room and BSF President Joe McKinney offered up stories of the supernatural to those seated around a campfire in the back yard as they roasted and snacked on marshmallows.

“We’ve had at least three or four different paranormal investigative groups here,” Geisler said. “I’ve had experiences in this house myself.”

The photo is of the BSF’s intrepid leader, Joe McKinney, telling ghost stories.

Now, I enjoy fun as much as the next guy, and I don’t mean to come across as a funkiller. However, how is this an appropriate activity for a supposedly serious preservation organization? This is the stuff that McKinney and the Board of Appeasers brag about in the BSF’s annual report, not the success of their efforts to preserve and maintain the battlefield. Apparently, the board’s major accomplishment this year has been toasting marshmallows with ghosts. It most assuredly was NOT preventing the destruction of core battlefield land by a landowner.

And then there’s this gem: Geisler said. “I’ve had experiences in this house myself.”

Do tell?

The BSF has made itself entirely irrelevant by engaging in such activities that have substantially less than nothing to do with the core mission of the organization, which is the preservation and stewardship of the battlefield. Please allow me to suggest that by engaging in such frivolous and undignified activities at a place where men suffered and died for a cause that they believed in dishonors them and their sacrifices. For shame.

Scridb filter The following article appeared on MSNBC today:

The following article appeared on MSNBC today:

Plan to honor teen Confederate spy splits Ark. town

David O. Dodd was barely 17 when he was hanged in January 1864By JEANNIE NUSS

updated 10/14/2012 2:55:32 PM ET

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — The story of David O. Dodd is relatively unknown outside of Arkansas, but the teenage spy who chose to hang rather than betray the Confederate cause is a folk hero to many in his home state.

Street signs and an elementary school in the state capital have long borne Dodd’s name, and admirers gather at his grave each year to pay tribute to Dodd’s life and death.

“Everyone wants to remember everything else about the Civil War that was bad,” said one of them, W. Danny Honnoll. “We want to remember a man that stood for what he believed in and would not tell on his friends.”

A state commission’s decision, though, to grant approval for yet another tribute to Dodd has revived an age-old question: Should states still look for ways to commemorate historical figures who fought to defend unjust institutions?

“(Dodd) already has a school. I don’t know why anything else would have to be done to honor him,” James Lucas Sr., a school bus driver, said near the state Capitol in downtown Little Rock.

Arkansas’ complicated history of race relations plays out on the Capitol grounds. A stone and metal monument that’s stood for over a century pays tribute to the Arkansas men and boys who fought for the Confederacy and the right to own slaves. Not far away, nine bronze statues honor the black children who, in 1957, needed an Army escort to enter what had been an all-white school.

“He was barely 17 years old when the Yankees hung him” on Jan. 8, 1864, Honnoll said. “Yeah, he was spying, but there (were) other people that spied that they didn’t hang.”

Dodd is certainly not the only teenager to die in the war or even the lone young martyr, said Carl Moneyhon, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock history professor.

“If you start talking about the 16-, 17- and 18-year-olds who were killed in battle, the number is infinite,” Moneyhon said. “There are tens of thousands of them. They become unremarkable.”

So it seems all the more curious that some have come to portray Dodd as Arkansas’ boy martyr.

“It’s part of the romanticizing of the Civil War that began in the 1880s and the 1890s, that looks for … what could be called heroic behavior to celebrate in a war filled with real horrors,” Moneyhon said.

And it’s caught on, though many question why.

“It’s a very sad story, but at the end of the day, Dodd was spying for the Confederacy, which was fighting a war to defend the institution of slavery,” said Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Sharon Donovan — who lives on West David O. Dodd Road (there’s an East David O. Dodd Road, too) — said she wouldn’t mind another Dodd namesake in her neighborhood.

“The fact that we live in the South, I could understand why he would want to do it because he was actually working for us in a way. … For that era, I think it was probably a noble thing to do,” Donovan said.

About a half-mile away, a banner outside an elementary school proclaims, “David O. Dodd Committed to Excellence.” A doormat bearing Dodd’s name shows a black boy smiling next to a few white ones. About half of the school’s 298 students last year were black and only 27 were white.

Jerry Hooker, who graduated from Central High School years after the desegregation standoff over the Little Rock Nine, lives at the site where he says Dodd was detained almost a century and a half ago. The Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission approved his application and agreed to chip in $1,000 for the marker noting the spot’s historical significance.

Hooker, 59, said the move to commemorate Dodd is not about honoring slavery, but about remembering the past.

“I don’t think it has a thing to do with race whatsoever,” Hooker said. “He was a 17-year-old kid with a coded message in his boot that had enough of whatever it is in him that he didn’t squeal on his sources.”

Still, in a city that stripped “Confederate Blvd.” from its interstate highway signs shortly before dignitaries arrived in town for the opening of Bill Clinton’s presidential library, the question remains: Should Dodd’s name be etched into another piece of stone or metal for posterity’s sake?

“There are currently more monuments to David O. Dodd than any other war hero in Arkansas,” Potok said. “You would think that at some point it would be enough.”

This debate is a microcosm of the ongoing debate of just how prominent should Confederate history be. Kevin Levin, Brooks Simpson, and Corey Meyer have done a superb job of documenting some of the outrageous and really silly things that a lot of the advocates for so-called “Southern Heritage” (whatever that might be) claim (for what Brooks Simpson describes as “the gift that keeps on giving”, look here).

This debate is a microcosm of the ongoing debate of just how prominent should Confederate history be. Kevin Levin, Brooks Simpson, and Corey Meyer have done a superb job of documenting some of the outrageous and really silly things that a lot of the advocates for so-called “Southern Heritage” (whatever that might be) claim (for what Brooks Simpson describes as “the gift that keeps on giving”, look here).

What role should these Confederate heroes continue to play in modern society? This is a real hot button question due to the racial implications that arise for those large elements of society that equate the Confederacy with the abomination of slavery, and who, rightly or wrongly, consider anyone who supported the Confederacy a racist. What role should the Confederate flag play in modern society, given its implications as a symbol of the perpetuation of the institution of slavery? Is it appropriate to honor someone who died in the service of a rebellion against the United States government?

I have many friends with Confederate ancestors, and I understand their desire to honor the sacrifices made by their ancestors. At the same time, I have no time for, or sympathy for, anyone who says that heritage is more important than accurate history, as our friends at the gift that keeps on giving like to say. They lash out at anyone whom they think has somehow denigrated their “heritage” (again, whatever that means) in particularly violent and unpleasant rhetoric (which I expect them to do as a result of this post, not that I care a whit). Many of them are neo-Confederates and/or Lost Causers, and they use these red herring arguments to push their own twisted political agendas. They denigrate what they call “political correctness”, but the reality is that one man’s symbol of “heritage” is another man’s symbol of slavery. How do we strike that balance?

I don’t have a good answer to the big question. I don’t think anyone does. However, I view this specific question as one of local politics, and if a majority of the people in the town believe that paying further tribute to David O. Dodd is appropriate, then that’s their business.

Sooner or later, though, we as Americans will need to reconcile these issues, because they will not go away any time soon. It’s a dialogue that we as Americans need to have, but how to do so without it denigrating into personal attacks is the mystery that needs to be resolved before it can happen. Let’s hope that we can figure out the answer to that problem sooner than later.

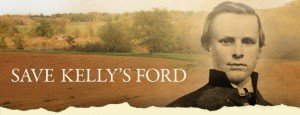

Scridb filter While I’ve known about this for some time, it’s only just become a matter of public knowledge, and I’m excited about this preservation opportunity.

While I’ve known about this for some time, it’s only just become a matter of public knowledge, and I’m excited about this preservation opportunity.

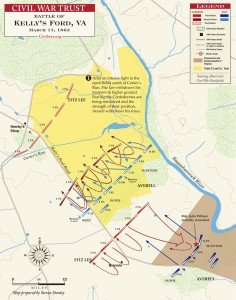

The Civil War Trust has announced a campaign to raise funds to pay for 964 acres of core battlefield land at Kelly’s Ford, near  Brandy Station. This represents almost 50% of the battlefield from the important March 17, 1863 cavalry battle between William Woods Averell and Fitz Lee’s troopers. The map shows where this particular parcel may be found. The land in yellow is the land in question. It was the scene of the most severe fighting of the battle. Click on the map to see a larger version of it.

Brandy Station. This represents almost 50% of the battlefield from the important March 17, 1863 cavalry battle between William Woods Averell and Fitz Lee’s troopers. The map shows where this particular parcel may be found. The land in yellow is the land in question. It was the scene of the most severe fighting of the battle. Click on the map to see a larger version of it.

With this large acquisition, combined with the significant portion of the battlefield owned by the Commonwealth of Virginia, nearly 75% of the entire battlefield will be safe. This is a rare and exciting preservation opportunity and one that I hope all of you will get behind.

It’s important to note that no river crossing saw more traffic during the Civil War than did Kelly’s Ford. Much of the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock River there on its way to Chancellorsville, there was an infantry fight there in November 1863, and two of the three divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps crossed there on its way to fight the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. This was probably the most famous and most important river crossing of the war, and the opportunity to preserve it is a rare one indeed.

It bears noting that this piece of the battlefield falls squarely within the bailiwick of the Brandy Station Foundation, which proudly touts that it’s going to hold an event to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford next March. However, the BSF did absolutely nothing whatsoever to help to arrange this deal or to help to raise awareness of it. Why? Because it’s got nothing to do with ghost hunting, relic hunting, or the Graffiti House (which are the things that the BSF bragged about in its 2011 annual report), and because President Joe McKinney and his board of appeasers have rendered the organization completely and entirely irrelevant. They’re just as irrelevant to this acquisition as they are to the ongoing efforts to acquire Fleetwood Hill–that is to say, wholly inconsequential. It is pathetic that the organization tasked with preserving the battlefield land in and around Brandy Station has been rendered so irrelevant that it probably had no idea that the Trust had made this deal before it was announced publicly on the CWT website today.

Because of that, all donations to preserve the Kelly’s Ford battlefield should be directed to the Civil War Trust and ONLY to the Civil War Trust. Send a message to McKinney and the Board of Appeasers: send them a copy of your donation check and let them know that if they were doing the job that they were sworn to do, that money would be coming to them and not to the Trust.

Thank you for your support for our efforts to save this important battlefield land.

Scridb filterThis Saturday, October 13, 2012, is Ohio Day at the Antietam National Battlefield.

I will be speaking at the Antietam battlefield Visitor Center at 11:00 this Saturday morning on Ohio at Antietam as part of the Ohio Day festivities. If any of you are around and might be able to make it, I hope to see you then and there. Mark Holbrook of the Ohio Historical Society will also be speaking, at 2:00, on the future presidents from Ohio who served in the Civil War. Two, William McKinley and Rutherford B. Hayes, were both at Antietam. Also, the Ohio Civil War 150 Traveling Exhibit will be set up in the Visitor Center for the day, so please take the time to check out this interesting exhibit of how Ohioans impacted the Civil War.

Antietam has long been one of my favorite battlefields, and I enjoy any opportunity to visit it. Come see me there!

Scridb filterOld friend John Hennessy has written a very interesting post on the Mysteries and Conundrums blog, wherein he addresses the positives and negatives of doing in-depth historical Internet research. I’ve been the beneficiary of John’s largesse–he has shared many of the cavalry-related newspaper articles that he has found with me, including as recently as last week when sent me an entire run of 22 articles by a trooper of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry that appeared in a long-defunct newspaper from Vevay, Indiana called the Vevay Reveille. I’ve actually been toying with the idea of transcribing them all and posting them here.

John is, of course, absolutely correct. Internet access to newspapers–some of my favorite sources, by the way–makes it possible to search for this material almost endlessly. But, as John also correctly points out, you definitely hit a point of diminishing returns, usually sooner than later. Quotable quotes are great, of course, but spending hours pouring through stuff for a single quotable sentence becomes a real question of diminishing returns. At some point, you have to decide, “I’ve fought the good fight on the research. It’s now time to put pen to paper and see what I can do with this story.” That means quitting the research process–and accepting the inevitable truth that you will never find EVERYTHING on a Civil War subject–and taking your best shot at writing whatever it is that you’re going to write about. That’s a very difficult thing to do, because you WANT to find everything, but the truth is that you won’t.

When we were writing One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863, the amount of material available on sites like Google Books and the Internet Archive meant that we spent hours and hours and hours searching for material. It meant that we used over 1100 sources in writing the book, but it also meant countless hours of searching, reams of paper and several toner cartridges printing, and then incorporating the material. Don’t get me wrong–I am EXTREMELY proud of what we accomplished with that book, and with the extent and amount of research we invested in it–but I never imagined that we would end up looking at and citing to more than 1100 sources when we started the project, and had that mountain of material not been so readily available, we never would have used as much as we did. We finally had to say “enough” and pull the plug on the researching because we realized that we had hit the point of diminishing returns.

As John correctly points out, the availability of these materials only makes it tougher to know when to call it quits on the research. It’s a fight I constantly fight.

Scridb filter The following report of the activities of the 1st Vermont Cavalry during the Gettysburg Campaign, written by its temporary commander, Lt. Col. Addison W. Preston, does not appear anywhere in either the Official Records or the Supplement to the Official Records. Preston wrote this report during the retreat from Gettysburg on the same day that the nasty fight at Funkstown occurred. It was published in the Rutland, VT newspaper on August 8, 1863, and differs from the report that appears in the Official Records. It was one of the new sources that I employed in preparing the second edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions. Since it is not available to the public, I thought I would share it here. Enjoy.

The following report of the activities of the 1st Vermont Cavalry during the Gettysburg Campaign, written by its temporary commander, Lt. Col. Addison W. Preston, does not appear anywhere in either the Official Records or the Supplement to the Official Records. Preston wrote this report during the retreat from Gettysburg on the same day that the nasty fight at Funkstown occurred. It was published in the Rutland, VT newspaper on August 8, 1863, and differs from the report that appears in the Official Records. It was one of the new sources that I employed in preparing the second edition of Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions. Since it is not available to the public, I thought I would share it here. Enjoy.

Boonsboro, Md., July 10

P. T. Washburn.

Adj. and Insp. Gen. of Vt.,Sir:

I beg leave to make the following report of engagements of the 1st Vermont Cavalry with the enemy in Maryland and Pennsylvania, from June 30 to July 8, 1863. At Hanover, Penn., June 30, aided in repelling an attack by General Stewart’s forces. Cos. M and D, under Capts. Woodward and Cummings, charged through the town, repulsing the enemy and capturing many prisoners. The rest of the regiment supported a battery until the enemy were driven from the field.

At Huntersville, Penn., July 2, in an attack upon the left of Gen. Lee’s army, this regiment was deployed as skirmishers, and subjected to a severe fire from the enemy’s batteries.

July 3, in the attack made by Gen. Kilpatrick on the right flank of the enemy at Gettysburg, this cavalry had the advance. Cos. A, D, E and I, dismounted, were deployed as skirmishers and soon drove the enemy’s skirmishers back of their main lines. The contest was continued by the opposing batteries and dismounted carbineers until 5 o’clock P.M., when Gen. Farnsworth, commanding the brigade was ordered to charge the enemy strongly posted behind stone walls and in the woods, which proved to be Maj. Gen. Hood’s division of infantry. With the 1st Va. Cavalry on the left and the 2d battalion of the 1st Vt. under Maj. Wells on the right, Gen. Farnsworth dashed forward closely followed by his men, leaping one stone wall under a severe fire. Our force drove the enemy in all directions. They then passed over another stone wall and through the enemy’s skirmish line and toward the Rebel batteries and succeeded in piercing the enemy’s 2d line, where many of our dead were found. I moved to the support of the 2d Battalion, with the 1st under Capt. Parsons, and a part under Capt. Grover. On the hill between the two walls we encountered a fresh regiment of the enemy, sent in from the right to intercept the retreat of our first column and to re-establish their lines. The struggle for this hill became most desperate but was at length carried by our boys with severe loss, the greater part of the enemy being captured. Our loss this day in killed, wounded and missing, was 75 men.

July 4th, we marched 50 miles to the rear of the enemy, and on the morning of the 5th at Lightersville, Md., captured one hundred prisoners, a drove of cattle and several wagons, and marched to Hagerstown the same night, twelve hours in advance of Lee’s army.

July 6th, our division attacked the retreating enemy at Hagerstown. Cos. D and L dismounted here, drove the enemy from a strong position and occupied it; Cos. A and D held a portion of the town against a superior force until ordered to retire in the afternoon, when a portion being cut off, were secreted by the Union citizens until our forces reoccupied it on the 12th.

In the retiring of this division at night on the Williamsport Road in the face of Lee’s army, this regiment formed a part of the rear guard, and suffered severely from assaults made upon it by superior numbers. Twice we were nearly surrounded. Capt. Beaman, with the 3d squadron, whom I ordered to hold a strong position, being cut off was ordered to surrender. He coolly replied, “I don’t see it,” and leaped a fence and by a flank movement escaped with his nearly entire force. Capt. Woodward, of Co. M, a brave officer, was killed at the head of his men, strongly resisting the advancing foe. The charge was now made by Co. K, under Capt. Grover, upon the main column of the enemy, which aided materially in checking their progress. A battery was now opened upon us by the enemy in the direction of Williamsport, and being thus attacked in front and rear we drew off under cover of night to the Sharpsburg Road on the left.

July 8, Gen. Stewart with a large force attacked our cavalry at Boonsboro early in the morning. The 1st Vt. was held in reserve until the afternoon, then it was sent by detachments to various parts of the field to strengthen our lines. At sundown a spirited charge was made by the 2d battalion under Major Wells upon the retreating enemy, and the sabres were freely used on both sides. Were I to give you a list of the meritorious it would comprise the names of every officer and enlisted man engaged.

I remain your very ob’t serv’t,

A. W. Preston,

Lt. Col. Com’g 1st Vt. Cavalry

Here are a few notes on this report:

1. A small part of the microfilmed copy of the newspaper article addressing Farnsworth’s Charge–part of one sentence–is obscured and is difficult to read. I made my best guess at what it says and I think it’s correct, but I’m not entirely certain.

2. The Huntersville that Colonel Preston refers to is actually the town of Hunterstown, PA, which is approximately 8 miles from the main battlefield at Gettysburg. There was a meeting engagement there between Kilpatrick’s division and Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Confederate cavalry brigade there on the afternoon of July 2, 1863.

3. The Lightersville referred to by Colonel Preston is actually the town of Leitersburg, MD, which is located a short distance from Hagerstown. Kilpatrick sent the 1st Vermont in the direction of Leitersburg on the morning of July 5 to pursue a Confederate wagon train while the rest of the Third Cavalry Division went to Smithsburg, where it spent most of the day skirmishing with Confederate cavalry and horse artillery before retreating to Boonsboro, where Kilpatrick’s division joined Brig. Gen. John Biford’s First Cavalry Division.

4. The regular commander of the 1st Vermont Cavalry during the Gettysburg Campaign was Col. Edward B. Sawyer, and Preston was normally second in command. Col. Sawyer was on medical leave, putting Preston in command of the regiment in his absence. Sawyer reported back to the regiment on July 10, 1863, the day that Preston penned this report. Sawyer’s return to duty may explain the otherwise odd timing of this report, considering that the campaign was still under way and that the armies were still north of the Potomac River on that date. Preston was killed in action on June 3, 1864 at Hawes Shop, Virginia. Preston was a good and brave soldier. He will soon be the subject of a forgotten cavalryman profile that I’m working on.

This photo is of the monument to the 1st Vermont Cavalry and sits near the spot where Elon J. Farnsworth was killed while leading the eponymous but unsuccessful charge on the afternoon of July 3, 1863.

This photo is of the monument to the 1st Vermont Cavalry and sits near the spot where Elon J. Farnsworth was killed while leading the eponymous but unsuccessful charge on the afternoon of July 3, 1863.

This account of the activities of the 1st Vermont Cavalry adds to our understanding of Farnsworth’s Charge by providing a different report, and it also adds to our understanding of the critical role played by the 1st Vermont during the retreat from Hagerstown to Williamsport after Kilpatrick was driven out of Hagerstown on July 6, 1863.

Scridb filterOn Thursday, September 20, I spoke to the Powhatan Civil War Roundtable. We were supposed to tie the speaking engagement to a visit with some Virginia friends, but the visit had to be postponed. That meant that Susan and I had to run-and-gun the trip. We drove out on Thursday and back on Friday. On the way back, we made a brief visit to the battlefield at White Sulphur Springs, where I paid my respects to Capt. Paul Freiherr von Koenig of William Woods Averell’s staff, who was killed while leading a flank attach on the afternoon of the first day of the battle.  Susan took the photo that appears here. I am standing next to the monument to von Koenig that marks the spot where he fell. This monument was erected by Bvt. Brig. Gen. James M. Schoonmaker in 1914 (at Schoonmaker’s own expense) and occupies the sport where the German adventurer fell. Sadly, much of the White Sulphur Springs battlefield has been destroyed by the development of a shopping center on the spot. The monument to von Koenig rests just outside a Hardee’s fast food restaurant, and if one did not know that this shopping center sits in the middle of a battlefield, there is no way to know.

Susan took the photo that appears here. I am standing next to the monument to von Koenig that marks the spot where he fell. This monument was erected by Bvt. Brig. Gen. James M. Schoonmaker in 1914 (at Schoonmaker’s own expense) and occupies the sport where the German adventurer fell. Sadly, much of the White Sulphur Springs battlefield has been destroyed by the development of a shopping center on the spot. The monument to von Koenig rests just outside a Hardee’s fast food restaurant, and if one did not know that this shopping center sits in the middle of a battlefield, there is no way to know.

Uncovering the facts von Koenig’s life story-and the story of how he died–and telling it in an appendix to my book on the Battle of White Sulphur Springs is, perhaps, the single piece of my historical work of which I am most proud (it turns out that Paul von Koenig became good personal friends with future President of the United States, Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield, which is one of the things that got me interested in Garfield’s service in the Civil War). I owe a great debt to the current Baron von Koenig, whose name is Dominik, and his son Florian, for helping me to put meat on the bones of this otherwise forgotten soldier.

We also stopped at the Old Stone Presbyterian Church in the lovely old town of Lewisburg, West Virginia.  The church and its cemetery are pictured here. For those unfamiliar with the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, the law library in the Greenbrier County Courthouse in Lewisburg was the object of Averell’s unsuccessful raid at the end of August 1863. There was one grave that I wanted to visit there, of an officer of the 22nd Virginia Infantry, who was killed during the fight at White Sulphur Springs. Along the way, we found the grave of another officer of the 22nd Virginia who played a significant role in the Confederate victory at White Sulphur Springs.

The church and its cemetery are pictured here. For those unfamiliar with the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, the law library in the Greenbrier County Courthouse in Lewisburg was the object of Averell’s unsuccessful raid at the end of August 1863. There was one grave that I wanted to visit there, of an officer of the 22nd Virginia Infantry, who was killed during the fight at White Sulphur Springs. Along the way, we found the grave of another officer of the 22nd Virginia who played a significant role in the Confederate victory at White Sulphur Springs.

This is the grave of Maj. Robert Augustus Bailey, who was a Lewisburg native. Nicknamed “Gus,” Bailey was born in Lewisburg in 1839. He was the son of prominent Circuit Judge Edward P. Bailey, which made his defense of the law library all the more notable. Gus Bailey became a lawyer himself and was practicing his trade in Fayette County in what became West Virginia when war came. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, he served as a captain In the 142nd Regiment Virginia Militia, 27th Brigade, 5th Division. With the coming of war, Bailey became captain of the Fayetteville Riflemen in Charleston on June 6, 1861. The Fayetteville Riflemen eventually became Company K, 22nd Virginia Infantry. The regiment was commanded by Col. George S. Patton, a prominent attorney from Charleston.

This is the grave of Maj. Robert Augustus Bailey, who was a Lewisburg native. Nicknamed “Gus,” Bailey was born in Lewisburg in 1839. He was the son of prominent Circuit Judge Edward P. Bailey, which made his defense of the law library all the more notable. Gus Bailey became a lawyer himself and was practicing his trade in Fayette County in what became West Virginia when war came. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, he served as a captain In the 142nd Regiment Virginia Militia, 27th Brigade, 5th Division. With the coming of war, Bailey became captain of the Fayetteville Riflemen in Charleston on June 6, 1861. The Fayetteville Riflemen eventually became Company K, 22nd Virginia Infantry. The regiment was commanded by Col. George S. Patton, a prominent attorney from Charleston.

On August 26,1861, Bailey led a small scouting party to determine the feasibility of placing artillery to shell the Federal camps at and near Gauley River Bridge. Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd implemented Bailey’s plan during the fight at Gauley River Bridge in November 1861. Bailey was promoted to major on November 23,1861, and often commanded the 22nd Virginia (or elements of it) in various battles, receiving particular notice for his bravery at Fayetteville, (West) Virginia, September 10,1862. On March 1, 1863, he was major in command of the Department at Lewisburg, (West) Virginia. He led a battalion of the 22nd Virginia at White Sulphur Springs, and played an important role in the Confederate victory there.

Bailey was trying to rally his defeated men at the November 6, 1863 Battle of Droop Mountain when he was mortally wounded. After saving the regimental colors, he was waving the flag when struck by the ball that took his life. He lingered for five days before dying, and was then buried in the Old Stone Church cemetery in his hometown of Lewisburg. Bailey played an important role in the story of the Confederate victory at White Sulphur Springs, and I just happened upon his grave serendipitously. I’m glad I found it and was able to pay tribute to a gallant Southern soldier who received his mortal wound while doing his duty.

Lt. John Gay Carr served in Co. H of the 22nd Virginia Infantry. He was known as “Gay Carr” to friends and family. Carr was born in Albemarle County, Va. in 1830, but had lived in Kanawha County (in what became West Virginia) for many years before the war. He joined Patton’s Kanawha Riflemen as a private in May 1861, and was promoted to lieutenant. He served gallantly in all of the battles of the 22nd Virginia–an active, hard-fighting regiment–until he was killed in action at the age of 31 at White Sulphur Springs on August 26, 1863. He was described as “a promising young man, had exhibited the noblest qualities of a soldier both in the ranks and as an officer, and his death was deeply mourned by his comrades and the people of his home county.”

Carr’s friend, regimental adjutant Lt. Rand Noyes, wrote, “In this battle the gallant Lieutenant Gay Carr, of the Kanawha Riflemen…fell with a bullet through his brain…in whose memory I learn a monument has been erected…in Lewisburg, which was the War Home of the 22nd Virginia Regiment. There were many other brave and gallant men who fell victims of death on this severely contested battlefield and whose memories deserve the richest pandits of tongue and men.”

In 1904, his friends contributed funds to raise the handsome tree trunk monument that stands silent sentinel over his grave in the cemetery of the Old Stone Church, which is pictured herein.

In 1904, his friends contributed funds to raise the handsome tree trunk monument that stands silent sentinel over his grave in the cemetery of the Old Stone Church, which is pictured herein.

You can see larger versions of the four images that appear in this post by clicking upon them if you so desire.

The story of the Civil War in West Virginia has long gotten short shrift, but it was truly a civil war there, with neighbors fighting each other to the death. If you’re interested in learning more, I recommend any of Terry Lowry’s excellent works on the battles fought in the Mountain State.

Scridb filterSeven years ago today, September 23, 2005, I made the first post on this blog. 1,263 posts later, I’m still here. And I have no intention of going anywhere. We’ve talked about a lot of different things here, and we’ve debated a lot of issues. I’ve enjoyed every minute of that.

Thank you to each and every one of you who takes the time to visit this blog and to indulge my rantings. Although I have never met many of you in person, I’ve come to view many of you as friends. I value the relationships that I have developed with people here, and I greatly look forward to continuing those relationships as we move forward.

Scridb filterChutzpah: unmitigated effrontery or impudence; gall; audacity; nerve.

Or, this is how the great Jewish writer Leo Rosten put it: “that quality enshrined in a man who, having killed his mother and father, throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan.”

I have a new definition of chutzpah, which appears on the home page of the website of the Brandy Station Foundation. That website indicates that the “Brandy Station Foundation Fall Picnic” will be held on September 29, 2012, “ATOP HISTORIC FLEETWOOD HILL”.

Let’s recall, shall we? This is the same Brandy Station Foundation that stood by and did absolutely nothing when the bulldozers began destroying “historic Fleetwood Hill” to build Lake Troilo, despite the president of the organization having advance knowledge that this critical piece of battlefield land was about to be devastated. This is the same Brandy Station Foundation that, instead of acting to fulfill its obligation as the steward of the land, issued a policy that said that destroying portions of the battlefield is acceptable if it’s done by a landowner there. This is the same Brandy Station Foundation that, instead of finding a way to purchase Fleetwood Hill from its present owners, stepped aside and then had the unmitigated gall to criticize the Civil War Trust for not acting quickly enough. This is the same Brandy Station Foundation that filled its 2011 annual report with bragging about its participation in ghost hunting and paranormal activity and not in battlefield preservation. This is the same board of the Brandy Station Foundation that has taken a once-great preservation organization and made it wholly and entirely irrelevant. And this is the same board of the Brandy Station Foundation that refused to allow the founder and multiple-term past president of the organization to renew his membership, claiming that he is somehow detrimental to the aims of the organization.

But yet, these people think holding a picnic on land that the BSF neither owns nor controls somehow excuses the horrific breaches of fiduciary duty perpetrated by this board and somehow justifies their rampant malfeasance.

And that, my friends, provides me with a completely new definition of the word “chutzpah” to use going forward. It’s the very definition of unmitigated effrontery and nerve, and it’s a real slap in the face to those who really care about preserving this battlefield.

Once again, I call for the resignation of Joseph McKinney and the Board of Appeasers before they further marginalize the BSF and render it completely and totally irrelevant.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like