The following article appeared on MSNBC today:

The following article appeared on MSNBC today:

Plan to honor teen Confederate spy splits Ark. town

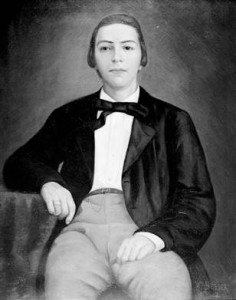

David O. Dodd was barely 17 when he was hanged in January 1864By JEANNIE NUSS

updated 10/14/2012 2:55:32 PM ET

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — The story of David O. Dodd is relatively unknown outside of Arkansas, but the teenage spy who chose to hang rather than betray the Confederate cause is a folk hero to many in his home state.

Street signs and an elementary school in the state capital have long borne Dodd’s name, and admirers gather at his grave each year to pay tribute to Dodd’s life and death.

“Everyone wants to remember everything else about the Civil War that was bad,” said one of them, W. Danny Honnoll. “We want to remember a man that stood for what he believed in and would not tell on his friends.”

A state commission’s decision, though, to grant approval for yet another tribute to Dodd has revived an age-old question: Should states still look for ways to commemorate historical figures who fought to defend unjust institutions?

“(Dodd) already has a school. I don’t know why anything else would have to be done to honor him,” James Lucas Sr., a school bus driver, said near the state Capitol in downtown Little Rock.

Arkansas’ complicated history of race relations plays out on the Capitol grounds. A stone and metal monument that’s stood for over a century pays tribute to the Arkansas men and boys who fought for the Confederacy and the right to own slaves. Not far away, nine bronze statues honor the black children who, in 1957, needed an Army escort to enter what had been an all-white school.

“He was barely 17 years old when the Yankees hung him” on Jan. 8, 1864, Honnoll said. “Yeah, he was spying, but there (were) other people that spied that they didn’t hang.”

Dodd is certainly not the only teenager to die in the war or even the lone young martyr, said Carl Moneyhon, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock history professor.

“If you start talking about the 16-, 17- and 18-year-olds who were killed in battle, the number is infinite,” Moneyhon said. “There are tens of thousands of them. They become unremarkable.”

So it seems all the more curious that some have come to portray Dodd as Arkansas’ boy martyr.

“It’s part of the romanticizing of the Civil War that began in the 1880s and the 1890s, that looks for … what could be called heroic behavior to celebrate in a war filled with real horrors,” Moneyhon said.

And it’s caught on, though many question why.

“It’s a very sad story, but at the end of the day, Dodd was spying for the Confederacy, which was fighting a war to defend the institution of slavery,” said Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Sharon Donovan — who lives on West David O. Dodd Road (there’s an East David O. Dodd Road, too) — said she wouldn’t mind another Dodd namesake in her neighborhood.

“The fact that we live in the South, I could understand why he would want to do it because he was actually working for us in a way. … For that era, I think it was probably a noble thing to do,” Donovan said.

About a half-mile away, a banner outside an elementary school proclaims, “David O. Dodd Committed to Excellence.” A doormat bearing Dodd’s name shows a black boy smiling next to a few white ones. About half of the school’s 298 students last year were black and only 27 were white.

Jerry Hooker, who graduated from Central High School years after the desegregation standoff over the Little Rock Nine, lives at the site where he says Dodd was detained almost a century and a half ago. The Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission approved his application and agreed to chip in $1,000 for the marker noting the spot’s historical significance.

Hooker, 59, said the move to commemorate Dodd is not about honoring slavery, but about remembering the past.

“I don’t think it has a thing to do with race whatsoever,” Hooker said. “He was a 17-year-old kid with a coded message in his boot that had enough of whatever it is in him that he didn’t squeal on his sources.”

Still, in a city that stripped “Confederate Blvd.” from its interstate highway signs shortly before dignitaries arrived in town for the opening of Bill Clinton’s presidential library, the question remains: Should Dodd’s name be etched into another piece of stone or metal for posterity’s sake?

“There are currently more monuments to David O. Dodd than any other war hero in Arkansas,” Potok said. “You would think that at some point it would be enough.”

This debate is a microcosm of the ongoing debate of just how prominent should Confederate history be. Kevin Levin, Brooks Simpson, and Corey Meyer have done a superb job of documenting some of the outrageous and really silly things that a lot of the advocates for so-called “Southern Heritage” (whatever that might be) claim (for what Brooks Simpson describes as “the gift that keeps on giving”, look here).

This debate is a microcosm of the ongoing debate of just how prominent should Confederate history be. Kevin Levin, Brooks Simpson, and Corey Meyer have done a superb job of documenting some of the outrageous and really silly things that a lot of the advocates for so-called “Southern Heritage” (whatever that might be) claim (for what Brooks Simpson describes as “the gift that keeps on giving”, look here).

What role should these Confederate heroes continue to play in modern society? This is a real hot button question due to the racial implications that arise for those large elements of society that equate the Confederacy with the abomination of slavery, and who, rightly or wrongly, consider anyone who supported the Confederacy a racist. What role should the Confederate flag play in modern society, given its implications as a symbol of the perpetuation of the institution of slavery? Is it appropriate to honor someone who died in the service of a rebellion against the United States government?

I have many friends with Confederate ancestors, and I understand their desire to honor the sacrifices made by their ancestors. At the same time, I have no time for, or sympathy for, anyone who says that heritage is more important than accurate history, as our friends at the gift that keeps on giving like to say. They lash out at anyone whom they think has somehow denigrated their “heritage” (again, whatever that means) in particularly violent and unpleasant rhetoric (which I expect them to do as a result of this post, not that I care a whit). Many of them are neo-Confederates and/or Lost Causers, and they use these red herring arguments to push their own twisted political agendas. They denigrate what they call “political correctness”, but the reality is that one man’s symbol of “heritage” is another man’s symbol of slavery. How do we strike that balance?

I don’t have a good answer to the big question. I don’t think anyone does. However, I view this specific question as one of local politics, and if a majority of the people in the town believe that paying further tribute to David O. Dodd is appropriate, then that’s their business.

Sooner or later, though, we as Americans will need to reconcile these issues, because they will not go away any time soon. It’s a dialogue that we as Americans need to have, but how to do so without it denigrating into personal attacks is the mystery that needs to be resolved before it can happen. Let’s hope that we can figure out the answer to that problem sooner than later.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Well said, Eric, and a useful, balanced perspective . Aside from the neo-Confeds, Lost Causers, and misfits who are cloaking their own bizarre theories and political agendas in the guise of “history”, it seems to me that there is a basic two-part question to be answered by well-intentioned folks who wish to honor individuals who sacrificed for a bad cause – (1) am I honoring the individual or the cause and (2) is there a risk that by doing the former I’m giving the impression that I’m doing the latter. I don’t know if this question gets asked often enough. F3U3

I’ve always liked the sentiment that Union veteran and writer Ambrose Bierce wrote after visiting his old battlefields in West Virginia and a place where Confederates were buried in ‘A Bivouac of the Dead’:

“They were honest and courageous foemen, having little in common with the political madmen who persuaded them to their doom and the literary bearers of false witness in the aftertime. They did not live through the period of honorable strife into the period of vilification–did not pass from the iron age to the brazen–from the era of the sword to that of the tongue and pen. Among them is no member of the Southern Historical Society. Their valor was not the fury of the non-combatant; they have no voice in the thunder of the civilians and the shouting. Not by them are impaired the dignity and infinite pathos of the Lost Cause. Give them, these blameless gentlemen, their rightful part in all the pomp that fills the circuit of the summer hills.”

Chris

Personal pride in one’s ancestors who served the Confederacy, even though I believe that pride to be misplaced and in some instances a cover for putrid things is understandable. New public monuments are different.

I do not see how one can separate the cause for which these people fought from the individual’s actions. Each new memorial is another opportunity to divide rather than unite us. We seem to do that a lot in many ways, and more is the loss for our nation.

Regards,

Dennis

It is easy to condemn slavery. As Lincoln said, “If slavery isn’t wrong then nothing is wrong.”

But the specific endorsements of slavery in the secession documents of some deep south states are not found in Arkansas or other upper south states. Moreover, Davis himself changed his mind about slavery stating specifically in July 1864 to Lincoln emissaries that ‘The south is not fighting for slavery, it is fighting for independence.” After Congress approved recruitment of slaves as soldiers, he backed it up with an executive order specifying that any slave accepted as a soldier much also be granted manumission papers.

Now, if you are going to let Lincoln change his mind about “not disturbing slavery in the states where it existed at the start of the war”, the it is necessary to permits Davis and the Confederacy to also change their War aims. Yet the common dogma of present-era historians only permits Lincoln to change his mind. It is a false dogma.

Dodd should be honored for giving up his life instead of betraying accomplices. One such accomplice was probably a teenage girl from Vermont.

“The South is not fighting for slavery. It is fighting for independence”. Well, let’s hold on there. What Davis supported by late 1864 was the manumission of slaves who enlisted as cannon fodder. I’m unaware of any sentiment for general emancipation – and, by the way, he obviously wasn’t speaking for the South even with that limited proposal because it was rejected. Davis had simply, and reluctantly, concluded that the South’s increasingly desperate military situation required getting troops from anywhere – even if it meant at the price of manumission limited to those who signed up. Even under Davis’s proposal, a victorious South still would have had slavery – albeit with a slightly reduced population of slaves. The South’s war for “independence” therefore still embraced the defense of the institution which led to secession in the first place.

1. Davis’ statement was made in July 1864 to two Lincoln peace emissaries. The chief reason it is in the historical record is that Lincoln used the comment *against* Davis by proclaiming that Davis would never agree to reunion and that the war must go on.

Thus, *Lincoln* still put reunion ahead of emancipation. Moreover, “reunion” was nothing more than a code word for Yankee hegemony in North America. That is what resulted in the ensuing 100 years, and that is what Davis wanted to avoid.

2. Davis *may* have made similar statements earlier, but historians don’t look for them because it does not conform to the false southerners-are-alway-evil dogma.

3. Certainly other prominent Rebels supported conditional emancipation earlier including Cleburne and 11 other Army of Tennessee officers in December, 1863. Cleburne’s proposal provided for manumission of the slave-soldier’s entire family. Kenner of Louisiana was even earlier.

4. Foskett discredits Davis’s decision to grant freedom to slaves in exchange for volunteering as Confederate soldiers. because it is motivated by a desire for a new military weapon. He thereby falsely implies that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation lacked similar motives.

In point of fact, the Emancipation Proclamation was *chiefly* adopted as a military and diplomatic weapon. Lincoln hoped it would (1) deter Confederate diplomatic recognition, (2) force the Confederate army to disperse troops in order to guard against slave uprisings, and (3) lead to defacto impressment of African-Americans into the Union army.

5. One reason Davis could not accept slaves into the army until March 1865 was because of his respect for constitutional procedures. The Congress of the USA was also more conservative than Lincoln, but Lincoln had less respect for the legal process. He did not wait for Congress to emancipate slaves whereas Davis did. This gets to the core of the differences between the two governments.

We can go at this all day, but it’s actually pretty simple. Davis was interested only in manumission for those who filled his desperate need for troops. There was no general emancipation agenda. (And we know for a fact that Lincoln was looking to emancipate generally, but had to settle for steps – which, of course, resulted in late 1864 in the Thirteenth Amendment being put forward). Moreover, even Davis’s limited proposition was flatly rejected by his colleagues – for the very good reason that they recognized why they had gone to war, and it wasn’t for “independence” with freed slaves. Spencer resorts to good old fashioned spin by suggesting that the reluctance here was based on devotion to constitutional principles. It wasn’t. The reluctance was because emancipation was the antithesis of everything that buttressed the decision to secede.

1. Evidently Foskett thinks denial is a river in Africa.

2. Yes, it *is* pretty simple. Lincoln was interested in emancipation chiefly as a weapon of war because it would damage the other side at no cost to his own.

3. Guys like Foskett often claim that states rights and independence were excuses made up by southerners after the War. But statements by Davis, Cleburne and others during the War demonstrate the error in such claims just as does the naming of Confederate General States Rights Gilst preceded Sumter by thirty years.

There *was *a fundamental difference between north and south in the primacy of states rights and conservative interpretation of the constitution. Pretending otherwise is common Yankee revisionism.

4. Foskett repeats standard Yankee hypocrisy by permitting Lincoln to change his war aims but not Davis.

5. I have ancestors on both sides of the War, but can readily concede the Yankee forebears shamelessly waged the war for economic domination of North America. I think they were wrong to do it. But I have no obligation of “heritage” to deny their selfish motivation and ruthless, cowardly conduct against helpless civilians.

John Foskett is from Boston where same sex marriage has been a state’s right since 2004.

If that is what Massachusetts wants, fine. I suspect that Foskett will agree the people of Arkansas have no right to interfere. But when it comes to a right of the people of Arkansas to honor the memory of David Dodd, well that’s different, see? Foskett hypocritically implies he has a right to intervene.

Furthermore, to repeat, the Arkansas secession document had *no* reference to slavery. About 80% of her families did not own slaves. But the did fight to repel invaders, and that’s a pretty satisfactory reason to fight.

Mr. Spencer,

You’re new here, so you get one warning, and one warning only.

To be quite clear about this: I pay for this website, so that means that I get to make the rules. The rules are what they are. I am the sole arbiter of them, and there is no right of appeal. Ever. If you don’t like the rules, there’s a simple solution: don’t bother coming back here, because they most assuredly are not going change just because you don’t like them.

There are three rules: (1) no posting under false or assumed names or anonymously (you’re okay with that one); (2) Be polite and respectful at all times; personal attacks are never acceptable and are never tolerated; and (3) nobody–and especially people whom I don’t know–gets to insult me on my own website.

Those are the rules. As I said, they are not negotiable, and there is no right of appeal.

Your comments are coming dangerously close to crossing the line on rule number 2. Again, I couldn’t possibly care less whether you think your comments are appropriate in tone or content. Your opinion about that subject is entirely irrelevant, as this is not a democracy. It’s a dictatorship with me as the benevolent despot, and when it comes to the application of the rules, my opinion is the ONLY one that matters.

Here is my ruling: Either dial back the snarky semi-personal attacks, or you’re gone. This is the one and only warning you will get. You will get no further warnings. There is no right of appeal. Make a comment that I think is inappropriate, it will be deleted, and your IP address will be permanently banned.

I trust that I have made myself abundantly clear.

Eric J. Wittenberg

Site Owner

Stating that a number of southern states did not include slavery in the documents outlining the rationale behind their secession is disingenuous at best. The lack of such documents from many states means you are doing nothing more than speculating.

Dennis: Good point. The other one I’d add is that Manning’s book a few years back made a strong case about the fallacy of assuming that because most southerners didn’t own slaves, slavery was not a large (if not the largest) factor in why they were fighting. Secession began and steamrolled because of the perception (right or wrong) that Lincoln’s election presaged a northern attack on an important (commercially and culturally) southern institution. One didn’t need to actually own slaves in order to decide that defending the institution of slavery was a worthwhile purpose.

That is also correct. I used to explain it to my students this way; the causes of the Civil War are like our solar system with a number of planets revolving around the sun.

The sun is slavery and the planets are all the other listed causes. Without the sun the solar system would not exist or go careening off into space. Absent slavery all the other “causes” would never have existed or been without resorting to armed conflict.

Rats! I left out a word above! the last sentence should have read …existed or been SOLVED (my caps) without resorting to armed conflict.

My apologies!

The shape and setting of the memorial in the photo reminds me of the one the DOC erected in Harpers Ferry to honor those blacks who didn’t abandon their owners for a silly thing like freedom during the Civil War.

Regards,

Dennis

If you think African-American slaves are not fully human, then the defense of the “peculiar institution”, or indeed its expansion, is worth fighting for. I submit this belief was common in the US pre-Civil War. Very few believe it now, which is why it is difficult for us to understand how people with otherwise noble qualities supported the institution of slavery.

That cited above has always been the justification for slavery. You know, like the term Untermenschen! In reality the belief in the inferiority of a group only influences WHO will be selected and not WHY slavery exists.

For those supporting the peculiar institution in the South it was all about maintaining the social, financial and political control of what was tantamount to a feudal aristocracy. Slaves allowed them to maintain control in those areas that free people who could become voters never would.

Regards,

Dennis