Month:

February, 2009

It would appear, based on the following e-mail, that the reports of the death of North & South magazine are premature:

Wasn’t there some street fighting in Baton Rouge? THis is Keith (editor) I’ve just got back from China, where among other things I’ve been laying the )production) groundwork for a return of MILITARY CHRONICLES later this year. Email was very intermittent while I was there, so i have a huge backlog to deal with. I understand that some rumor has been circulating that North & South might be going under. Suffice to say the word of our demise has been greatly exaggerated. Next isue goes to the printer in 7-10 days. The economic climate is creating some difficulties, and may mean some slippage in schedule and/or the occasional issue reduced to 84 pages (I’m trying to avoid this). But the magazine is not going to disappear. (The problem is that advertisers have had their budgets slashed, and this will remain a problem for the next 6 months). Anyone who is waiting for an email response from me, please bear with me. Will get back to you asap.

Keith

I guess that’s a good thing, if the quality issues are resolved and a new cartographer has been located. At least my investment remains afloat for another issue. Beyond that, who knows?

I believe that the task of running this business is probably more than Mr. Poulter can capably handle. I think that his renewed attempts to start a second publication are a very bad idea, as I think it more important–not to mention his legal and fiduciary duty to the shareholders–to fix the problems with North & South before trying to launch Military Chronicles. That includes not diverting a single resource of N & S for use with the new publication, as doing so would breach that duty.

The lawyer in me seems to think that putting the interests of Military Chronicles ahead of those of North & South constitutes a misappropriation of corporate opportunity for his own use and benefit, and an actionable breach of fiduciary duty, and were I still counsel to the company, that’s what I would advise him.

However, I’m just the dumb lawyer who’s on the outs. What do I know?

Scridb filterFrom the current issue of National Journal, we have the following article on John Latschar’s reign at Gettysburg:

LINCOLN BICENTENNIAL

A New Battle Rages At Gettysburg

Gettysburg National Military Park had a $103 million makeover, but conflict at the iconic site continues.

by Edward T. Pound

Saturday, Feb. 21, 2009GETTYSBURG, Pa. — In August 1994, John A. Latschar arrived here to take over as superintendent of the Gettysburg National Military Park, site of the most momentous battle of the Civil War. The longtime National Park Service ranger and decorated Vietnam veteran was appalled by what he saw: a battlefield in need of restoration; a 307-foot, privately owned tourist observation tower, widely reviled, looming over the Soldiers’ National Cemetery where Union soldiers were laid to rest and where President Lincoln delivered his immortal address in 1863; and a musty museum and visitor center that had seen far better days.

In the ensuing years, he began restoring important landscapes and led the Park Service’s effort to demolish the eyesore of the so-called National Tower, which was done in July 2000 and highly praised by the preservation community. He also set in motion plans for a new state-of-the-art museum and visitor center, using a partnership consisting of a private, nonprofit foundation and the Park Service.

As it turned out, that partnership venture became one of the most important arrangements in the Park Service system, which is always hard-pressed for cash. The new facility finally opened in April. A few months later, during a visit to the park, then — Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne called Latschar “a national treasure.”

A pretty rosy picture, to be sure. But the reality is a bit more complicated.

Latschar’s tenure at Gettysburg has been marked by repeated conflicts with some Civil War preservationists and others aghast at the mammoth size of the new museum-visitor center and by what they see as the lack of government supervision of the project and the Gettysburg Foundation, the Park Service’s controversial nonprofit partner. His plans for the park have led to clashes with battlefield guides, with local businesses, and with the family that contributed a famed collection of 38,000 artifacts to the park.

Now 61, Latschar gets things done. He is known within the Park Service for his “can-do” reputation — he loathes rules that get in the way — his mental toughness, and his ability to forge close relationships with higher-ups. But that tenacity can be a two-edged sword. To critics, he is someone more than willing to run over people who get in his way.

Behind the scenes, after Park Service staffers in Washington raised concerns in 2003 that a 139,000-square-foot museum and visitor center was too large and too expensive, Latschar went around them to a senior agency official who arranged a meeting with the director of the Park Service. The staffers were reprimanded, and a Park Service board swiftly approved the project’s comprehensive design, according to Latschar’s account of the incident. Without the approval, the project would have been delayed and might have required downsizing.

As the nation celebrates the 200th birthday of Abraham Lincoln this month, the long-running conflict at Gettysburg isn’t likely to end anytime soon. The heart of the conflict, to critics, boils down to this: promises made, promises not kept.

The museum-visitor center project initially carried a price tag of $39.3 million. In the end, it cost $103 million. While selling the public on its public-private partnership idea, the Park Service repeatedly maintained that the project would not need federal monies and would be financed solely with private donations, corporate sponsorships, and loans. That isn’t quite what happened. Over the years, Congress earmarked $15 million for the project — Rep. John Murtha, D-Pa., arguably the king of pork on Capitol Hill, arranged the funding — and the state of Pennsylvania tossed in another $20 million.

And from the get-go, Park Service and Gettysburg Foundation officials did not envision charging an admission fee for visitors to view the museum’s exhibits and collection of world-famous artifacts. But only six months after opening the center in April and projecting an annual revenue shortfall of nearly $1.8 million, officials imposed an admission fee of $7.50. The “all-in-one” fee also allows visitors to view other park attractions. But as one critic of the new policy pointedly noted at a public meeting, according to The Gettysburg Times, “it would take 52,364 people paying $7.50 just to pay” the foundation president’s annual salary of $392,735.

Meanwhile, Latschar’s conduct has come under government scrutiny. Investigators from the Interior Department, which includes the Park Service, are reviewing, among other issues, whether he misused $8,700 in funds from the park and a private group for construction of a fence on 4 acres of parkland -adjacent to his home. His wife, Terry, uses the pasture to exercise her horses under a park permit. In an interview, Latschar said he was confident that investigators would determine that he did nothing improper.

Although the inquiry’s breadth is unclear, the investigators from Inspector General Earl Devaney’s office also contacted the Gettysburg Foundation; they didn’t question anyone and were provided with a list of contractors on the museum-visitor center project, according to foundation officials. Investigators declined to comment.

Latschar has faced other ethics issues as well. Last November, after announcing he would retire from the Park Service and take over the lucrative presidency of the Gettysburg Foundation, critics accused him of a conflict of interest. They cited his extensive dealings with the foundation as Gettysburg’s superintendent. Indeed, Latschar played an important role in planning the museum project and in the agreements that the Park Service struck with the foundation to operate the facility. Interior Department lawyers, in an opinion issued last month, strongly suggested that moving over to the foundation would constitute a conflict. Latschar decided to stay in his government position.

High-Profile Partners

For many Americans, Gettysburg is sacred ground. Established in 1895, the 5,900-acre park 80 miles north of Washington remains a popular attraction; last year, about 1.5 million visitors viewed the ornate monuments and historical exhibits, walked the open ground, and climbed the stony hills where, on the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg unfolded in the pivotal clash of the Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army, seeking a decisive victory on Northern soil, was defeated by Union forces in a bloodbath that left 51,000 soldiers dead and wounded. In November, President Lincoln delivered his 272-word Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

Gettysburg’s public-private partnership experiment is a model that other parks can use to preserve and improve resources and facilities, officials explained. The reason for the partnership is pretty straightforward: Much like a beggar on the street, the National Park Service needs money. Created in 1916, the agency has an annual budget of only $2.5 billion, a pittance considering it must manage and maintain some of the nation’s most precious assets — 391 parks, including 24 Civil War sites. The Park Service also has a staggering deferred-maintenance backlog of nearly $9 billion in projects.

In speeches drumming up public support for the Gettysburg partnership, Latschar described the Park Service’s problems succinctly: “Why are we broke? Most simply stated, both Congress and the American public are in a love affair with national parks — but are not willing to pay for the consequences of their devotion.”

As the Park Service declares on its website, public-private partnerships are “a way to get things done.” The chief of the agency’s partnership program, John Piltzecker, said in an e-mail response to National Journal’s questions that “there have been numerous instances of partners raising all or part of the funds needed to help the [Park Service] accomplish its mission, whether it was a new or improved facility, the rehabilitation of a trail system, or the enrichment of park programming.” These partners include nonprofits, companies, and volunteers.

The way Latschar and Gettysburg Foundation officials see it, the partnership has been an unmitigated success and a good deal for the public. Latschar’s many critics don’t agree. “Let me put it as simply as I can,” said Franklin Silbey, a former congressional investigator, a Civil War preservationist, and a longtime thorn in Latschar’s side. “Latschar and the Park Service have repeatedly misled the public. The new museum costs three times more than it was supposed to. They said they didn’t need federal funds, yet they got $15 million in federal earmarks. The old museum and its artifacts used to be free. Now the public has to pay $7.50 a head just to walk in the museum door. A for-profit vendor sells trinkets on sacred ground. Need I say more?”

In a three-and-a-half-hour interview at his offices in the new facility, Latschar said he has always been truthful with the public. “From the very first speech on this project in January, February 1995 to today, I have never misled the public about a single thing. Everything that I’ve ever said has been based upon the best [information] that I knew and the best I believed at the time. It turned out in a couple cases that what I believed didn’t happen the way we thought it would, but there’s been absolutely no deceit involved.”

Latschar, who has a Ph.D. in American history, said he enjoys wide support among Civil War historians, preservationists, and local business leaders. They understand, he said, that a desire to protect Gettysburg’s treasures and to provide the public with high-quality interpretation of the Gettysburg campaign and its consequences has always motivated him. Some critics, he said, “are not going to be happy until I am dismissed from this position in disgrace. It’s unfortunate that it has sunk to that level.”

Lightning Rod

The massive museum-visitor center, with its fieldstone building and barn-like structure, was designed to look like a big Pennsylvania farm. It is about a half mile south of, and below, the old visitor center that sits on historic Cemetery Ridge. Inside the new facility is a large lobby; 11 exhibit galleries, based on phrases from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address; two theaters for viewing a 22-minute film, A New Birth of Freedom, narrated by actor Morgan Freeman; storage for artifacts; a library and reading room; a restaurant; and a book and gift shop. The center also houses the magnificent oil painting-in-the-round, known as the Cyclorama, which depicts “Pickett’s Charge” — Confederate Gen. George Pickett’s doomed advance on Cemetery Ridge that led to Lee’s crushing defeat. The restored painting measures 42 feet by 377 feet.

Under the Park Service’s agreement with the Gettysburg Foundation, the nonprofit owns the facility and receives significant revenues from its operations. Those revenues include some of the proceeds from the book and gift shop and a restaurant run by separate for-profit companies. The foundation also takes in all revenues from admission sales. The nonprofit must pay the operating and maintenance costs for the center — an arrangement, Latschar says, that saves the Park Service $300,000 annually — and retire $15 million in long-term debt. The agreement requires the foundation to donate the museum-visitor center and the land it sits on to the Park Service in 2028.

Initially known as the Gettysburg National Battlefield Museum Foundation, the nonprofit has had some esteemed board members; in the past decade they have included prominent Civil War historians and business leaders. Dick Thornburgh, the former Republican governor of Pennsylvania and later U.S. attorney general, continues to serve on the board.

From the beginning, more than a decade ago, critics of the partnership arrangement viewed it as a profit-making scheme for private interests. Robert Kinsley, a major construction contractor from York, Pa., put the foundation together after the Park Service selected him to develop the museum-visitor center.

Kinsley and Latschar are close. Indeed, as chairman of the foundation, Kinsley asked Latschar to take over as the nonprofit’s president last year, only to be disappointed when ethics questions forced Latschar to step aside. Like Latschar, Kinsley has been a lightning rod for criticism: Critics say he profited from Gettysburg Foundation work on the museum-visitor center, a charge he strenuously denied in an interview with National Journal.

Kinsley, chairman and CEO of Kinsley Construction, has repeatedly said that philanthropy, not profit, has motivated him. The chairman of the Gettysburg Foundation since its inception, Kinsley has donated nearly $8.4 million to the nonprofit through his family foundation, his personal funds, and Kinsley-owned partnerships, according to foundation officials. The gifts have included cash, forgiven loans, and donated real estate. The contributions, the officials say, make Kinsley the largest private donor to the project; the next-biggest donor gave $4.5 million.

At the same time, Kinsley’s construction company and another family-owned company, LSC Design, worked on the development of the museum-visitor center. The foundation’s decision to use the Kinsley companies, Latschar said, was approved by Park Service officials in Washington.

According to the Gettysburg Foundation, it has paid the companies a total of $8,509,825 for their work on the project. The foundation said that Kinsley Construction was “reimbursed” $1,332,550 for supplying equipment, drawings, supplies, and other items to the project. It paid another $3,461,275 to Kinsley Construction for providing construction management “at cost” and at “no profit,” the foundation said. Additionally, the foundation has paid $3,716,000 to LSC Design, which is headed by one of Kinsley’s sons, Robert II. Those fees, the foundation said, covered architectural design work for the museum-visitor building and other services, including structural, traffic, and civil engineering.

The senior Kinsley acknowledges that LSC Design got the design work at his suggestion. He said he suggested that the board hire LSC Design when he realized that the foundation could save money by using the firm run by his son. After foundation lawyers and the Park Service signed off on the arrangement, Kinsley said, the board gave its approval. Kinsley said he recused himself from all board discussions on the issue. Moreover, foundation officials said that an auditing firm, independent of Kinsley, is reviewing his companies’ charges.

Apart from the museum project, Kinsley’s construction company has worked as a major subcontractor on two contracts awarded by the Park Service in 2007 to a New Jersey company, Puente Construction Enterprises. Puente, a minority contractor under a U.S. Small Business Administration program, was hired to repave 19 historic roads, repair a bridge, and replace deteriorating water lines in the Gettysburg park.

The Puente contracts were worth nearly $4.1 million. The minority firm paid Kinsley Construction $2.5 million as the principal subcontractor on the park work, according to Barbara Sardella, general counsel for the Kinsley firm. In the interview, Kinsley said that his company’s work as a subcontractor “has nothing to do with the museum.” Both he and Latschar said that the park superintendent played no role whatsoever in his firm’s getting the work.

As for the foundation payments to his companies on the museum project, Kinsley said he was not profiting from the arrangement. “I made a promise when I went to Gettysburg that I would not profit from this or anything else in Gettysburg because of this,” Kinsley said. “I am very happy I have been able to contribute to Gettysburg the way I have. I just wish [critics] would do the same.”

The Price Of Preservation

Kinsley and park officials said that the ambitious museum project allowed them to convey to the public much more clearly the Gettysburg story and the battle’s consequences. The old facility, they said, did not do justice to the historical importance and emotional power of Gettysburg. “We only had one chance to do this,” Latschar explained, “and we wanted to do it right, as befits this hallowed ground.”

Even at its original cost estimate of $39.3 million in 2001, the Gettysburg project was the most expensive Park Service visitor center in the works. The Government Accountability Office reviewed 80 visitor center projects under construction or renovation and found that the “average cost to build a visitor project was $6.7 million.” But Gettysburg Foundation officials say that the report is misleading when applied to their project. “If you just looked at our visitor center piece of it, it’s probably not much more than that,” the foundation’s president, Robert C. Wilburn, told National Journal. “The real expensive part is the museum and the Cyclorama [painting]. We spent $15 million on the [restoration of] the Cyclorama painting alone.”

The Cyclorama is a historical icon painted in the 1880s by French master Paul Philippoteaux and a team of artists and is considered central to the park’s story line. The painting’s restoration is a prime example of why the cost of the project increased so dramatically — and why federal funds ended up in the mix. Back in 1997, the restoration was projected to cost $5 million. By 2002, the estimate had jumped to $6.6 million. By the time the restoration was completed and the painting was moved to the new museum-visitor center from the old facility, the cost had skyrocketed to $15 million — all paid for with congressional earmarks arranged by Rep. Murtha.

Other increases came from the cost of construction, design services, fundraising, exhibits, and landscape restoration. The foundation also expanded its role in the park. It merged with another foundation, which had long supported the park, and it recently spent $1.9 million to acquire an 80-acre farm, “protecting the historically significant site from private development, according to a foundation press release.

Wilburn, who formerly served as president and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, makes no apologies for the cost, or the size, of the Gettysburg center. “What I have said before,” he explained during an interview in his second-floor offices in the center, “is that I regret that we weren’t able to raise money to make it even better.” Wilburn went on, “The restaurant is too small for the summer, the gift shop gets jammed… it is not oversized.” Most visitors and professional reviewers have given the new center a big thumbs-up.

Wilburn also defended the decision to charge visitors an “all-in-one” fee of $7.50 to see the museum artifacts and exhibits, along with viewing the Cyclorama painting and A New Birth of Freedom. The foundation, he said, had planned to keep the museum free and charge a $12 fee to see the painting and film. But shortly after opening the center, he said, foundation officials and the Park Service realized that revenues couldn’t cover expenses. “We have had almost no negative comments about it,” he said. “People seem to think it’s a real bargain.”

That’s a difficult argument to make to descendants of Gettysburg resident John Rosensteel who, at the age of 16 in July 1863, began collecting artifacts from the battlefield just days after the guns fell silent.

Over the years, the Rosensteel family acquired Gettysburg and Civil War artifacts. The 38,000-piece collection, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, was donated to the government in 1971 by George and Emily Rosensteel. Pamela Jones, their grandchild and a resident of Gettysburg, said that the park should never have implemented a fee to see the artifacts. “The gift was made to the American people,” she said in an interview, “in the hope that the artifacts would always be viewed for free.” The collection includes the saddle cover used by President Lincoln when he rode on horseback from the town of Gettysburg to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, as well rifles, cannons, drums, uniforms, maps, photographs, and paintings.

According to Latschar, the old visitor center, which was built by George Rosensteel in 1920, will soon meet the wrecking ball, and demolition plans are also in the works for the cylindrical building that used to house the Cyclorama painting. But a group that favors preserving significant modern architecture is attempting in a federal lawsuit to block the demolition. The Cyclorama building was designed by the late modernist architect Richard Neutra, whose son, Dion, is a plaintiff in the case. Both buildings sit on Cemetery Ridge, one of the most historically significant battlefield sites in the park. The plan is restore the landscape to its 1863 appearance.

Speaking His Mind

Latschar operates the park on a relatively small budget. Along with the adjacent Eisenhower National Historic Site, the home of the late President Eisenhower, he has about $7.6 million annually to work with. In one four-year period, though, Congress gave him some extra money — $1.1 million over a four-year period — to help with historic landscape rehabilitation.

Latschar’s superintendent’s reports provide details on the park’s operations and funding — and a forum he uses to speak his mind. He made the reports available to National Journal, explaining that they were “a long-cherished tradition in the Park Service.” Latschar went on: “Historians start there. By tradition, it is the one report where the superintendent can say exactly what he thinks is important to put on the record. Nobody can change it. A copy goes straight to the National Archives.”

The reports offer frank assessments of some critics, even the few who emerged occasionally in Congress. In his 1999 report, Latschar suggests that then-Rep. Ron Klink, a Democrat who opposed the museum project, was nothing but a political opportunist. He wrote that Klink, who was running for the Senate against the incumbent, Rick Santorum, “was virtually unknown in the central part of the state”‘ and “apparently decided that he needed a ‘name recognition’ issue.”

At the same time, Latschar heaped praise in his reports on Santorum, a big supporter of the project, once even describing the Republican as a “hero.” Latschar wasn’t too happy, though, when the GAO reviewed the partnership arrangement in 2001. He wrote that the GAO “seemed obsessed with what the partner [Kinsley] gets out of the partnership,” adding: “When told ‘nothing but the good feeling of making a difference,’ they were obviously unconvinced, a sad indication that philanthropy is not well understood inside the Washington Beltway.”

Latschar describes how Murtha repeatedly arranged for earmarks to fund the Cyclorama restoration, and details the historic landscape rehabilitation at the park, including the removal of “nonhistoric” woods, the replanting of orchards, the construction of a historic fence, and the removal of a “major nonhistoric structure” that once housed an automobile dealership.

He doesn’t let roadblocks stand in his way. Witness his dispute with the construction management staff of the Park Service’s Development Advisory Board over the comprehensive design for the museum-visitor project. In the end, Latschar prevailed, but had he failed at the DAB level, the project could not have gone forward without being scaled back; the board must review and sign off on all major construction projects.

Latschar, in an annual report, described what happened: “Showing a human foible… all too common, the staff of the DAB seemed overly concerned that the Museum Foundation was building too large a complex and spending too much money, even though the Foundation was taking all the risks, and the [National Park Service] was taking none.” In October 2003, he wrote, “we had a highly unsatisfactory call with the Washington Office construction management staff. The staff of the Museum Foundation was insulted by the unprofessional treatment and skepticism they received from the NPS staff. I was embarrassed.”

Latschar contacted a senior Park Service official who arranged for a meeting between the foundation and Fran Mainella, then the director of the Park Service. “The Director apologized to the Foundation,” Latschar wrote, “and promised to be personally present at the Foundation’s presentation to the Development Advisory Board on November 4, 2003.”

Mainella, Latschar, and the DAB and some of its staff members attended that subsequent meeting in Washington. According to Latschar’s report, “Rob Kinsley, the project architect, presented a superb power-point presentation” detailing how the design was developed. “There were relatively few questions asked, and none with any merit,” Latschar wrote. “In the end, the project was approved.”

Latschar makes no apologies for going over the heads of the DAB’s staff. He told National Journal that Mainella “reprimanded” the staffers for insulting the Kinsleys and others involved in the project.History As Judge

Now, with Interior’s IG reviewing the Gettysburg partnership and the museum-visitor center project, Latschar, at least outwardly, exudes an air of confidence. He said he was recently questioned by investigators who had “just swept up” every allegation “and decided it made sense to ask the questions.” They mostly wanted to know about “the birth and evolution and the maturation of the partnership.” The investigators asked him, he said, about the Gettysburg Foundation’s use of companies affiliated with the senior Kinsley, the foundation’s chairman, and “a few other odds and ends.”

Latschar acknowledged that investigators are also exploring whether he had misused park and nonprofit funds to replace a wire fence around 4 acres of park land at the back of his 2-acre home. His wife uses the pasture for her two adult horses and a yearling under a “special-use permit” issued by the park. The Park Service replaced three sections of the fence in 2002; it replaced another section late last year. The total cost was $8,700.

Under the park’s “agricultural lease program,” Latschar said, Terry Latschar pays $75 a year for the permit, which he said was consistent with similar arrangements in the park. His wife first obtained the permit in August 1999, or two years before the couple was married. Under the arrangement, John Latschar said, she is responsible for maintaining the park pasture and repairing the wire fence. “But when it comes time that the fence is beyond repair and needs to be replaced,” he said, the permit requires the Park Service to replace the fence. “That’s the Park Service responsibility,” he explained.

Indeed, the permit does require her to maintain the fence but it does not contain a clause requiring the park to replace the fence. When asked about this in a later interview, Latschar acknowledged that there’s nothing in his wife’s permit requiring the park to replace the wire fence. Nonetheless, he said, the “practice” of the park has been to replace deteriorated fencing in such cases. In a follow-up e-mail, he cited other instances in which the park had replaced fencing on parkland used by other permit holders. The park, Latschar said, acts under broad authority to “preserve resources and, or, protect visitors.”

The park spent $3,910 to replace “505 feet of No Climb Horse Fence” last year, according to the contract with the contractor who did the job. An explanation from the park’s maintenance division says that “the fence is an emergency replacement as a very large section of the fence has been destroyed from a horse being entangled in the fence.”

Earlier, in March 2002, Latschar used funds from a nonprofit to replace 1,126 feet of the pasture fence. The $4,800 job was billed to Eastern National, a nonprofit that operated the bookstore in the old visitor center and provided funds for preserving the park. The purchase order includes Latschar’s note that the new fencing will “prevent livestock from getting out in the vicinity of Sedgwick equestrian monument.”

Latschar said he did not “pressure” the park’s maintenance chief to replace the fencing and there was “not a frigging chance” that he had acted improperly.

Even today, 146 years after Americans spilled blood on this hilly farm country, controversy at Gettysburg never seems more than a musket shot away. And John Latschar, a man whose self-confidence and take-no-prisoners style brings to mind the brash generals of the armies that clashed here, is convinced that history will treat him well.

Asked to list his accomplishments, he ticks off the removal of the National Tower, the landscape restoration program, and the partnerships formed with the Gettysburg Foundation and local townspeople. His legacy, Latschar is convinced, is to have helped preserve a transcendent moment in the nation’s past and literally enshrine the battle in its rightful place as a turning point in the Civil War.

However his tenure at Gettysburg concludes, Latschar clearly doesn’t mind being on the hot seat. But like everything connected to Gettysburg and the Civil War, the debate over actions, consequences, and meaning never comes to an end.

Something continues to smell bad about all of this…..

Scridb filterI’ve been a student of the Battle of Gettysburg for about 40 years. I have seen a lot of strange and even bizarre things about the battle, and I’ve met a lot of people who share my fascination with it. I have even met a few who had an overarching, Gettysburg-only focus, to the exclusion of all other aspects of the Civil War, which is something I just have never understood.

However, I have never seen anyone with a dedication to the Battle of Gettysburg like Dennis Morris. Visit his website. But prepare to be blown away before you do. I’ve never seen anything that reflects dedication to the Battle of Gettysburg that comes close to holding a candle to Dennis’ work….

Check it out.

Scridb filterThis is a profile of a forgotten cavalryman that I’ve wanted to do for some time. I owe Ranger John Hoptak a big debt of gratitude for passing along the missing material that I’ve long wanted but have been unable to obtain. Thanks, John.

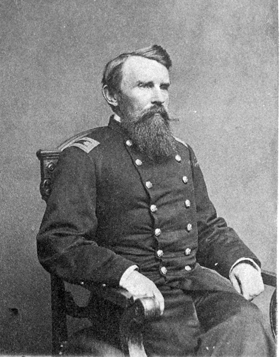

Forty-seven year-old Maj. Charles Jarvis Whiting of the 5th U.S. Cavalry led the Reserve Brigade. Whiting was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts on November 28, 1814 and was raised in Castine, Maine, and from the time of his childhood, his overarching ambition was to become a West Point cadet. When he received his appointment, he made the trip to West Point and was turned away for being too short. He spent the next year hanging from trees with a brick tied to each foot, hoping to stretch himself enough to meet the height requirement. He returned to the Academy the next year and was admitted. He graduated fourth in the Class of 1835.

Forty-seven year-old Maj. Charles Jarvis Whiting of the 5th U.S. Cavalry led the Reserve Brigade. Whiting was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts on November 28, 1814 and was raised in Castine, Maine, and from the time of his childhood, his overarching ambition was to become a West Point cadet. When he received his appointment, he made the trip to West Point and was turned away for being too short. He spent the next year hanging from trees with a brick tied to each foot, hoping to stretch himself enough to meet the height requirement. He returned to the Academy the next year and was admitted. He graduated fourth in the Class of 1835.

He was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery and served engineering duty during the Seminole War in Florida. He resigned his commission on May 31, 1836 to become a railroad surveyor in the Florida panhandle. In 1838, he served as the assistant engineer for the survey of the Mississippi River delta. He then settled in Maine, where he established, and served as headmaster of, the Military and Classical Academy in Ellsworth, which a promising young student named Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain attended. He married in June 1841, and had a daughter. His wife died in 1847, leaving Whiting a 33-year-old widower with an infant daughter, Anna Waterman Whiting. His wife’s family raised Anna, for the Army was no place for an infant.

After teaching for six years and with his wife dead, Whiting surveyed the boundary between the United States and Mexico that was established by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Whiting then settled in San Jose, California, where he farmed and surveyed. For the years 1850-1851, he served as Surveyor-General of California.

When the size of the Regular Army was increased in 1855, a new regiment of light cavalry was formed. On March 3, 1855, Whiting was commissioned a captain in the newly formed 2nd U.S. Cavalry (which was re-designated as the 5th U. S. Cavalry in 1861). He saw extensive action in the west, fighting against Comanche Indians on several occasions, and earning praise for his valor in combat. The New Englander was known as an ambitious martinet who was eager to advance his own career. The coming of Civil War gave him that opportunity.

In March 1861, at the height of the secession crisis, Whiting was stationed at Fort Inge in Texas. When Texas left the Union, he and other loyal officers were stranded there. Whiting and Capts. George Stoneman and James Oakes met to discuss how to escape. They pondered the possibility of trying to escape to the Jefferson Barracks via the Indian country. However, they had insufficient supplies and no transportation, so they abandoned the plan. Stoneman and Whiting eventually found their way back to Washington, D. C. on a steamboat. Whiting was assigned to teach new recruits basic cavalry tactics at the Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. He also took a brief furlough to return home to Maine to marry Phebe Whitney, the younger sister of his brother’s wife.

A veteran officer like Whiting was needed at the front, and he was immediately called to rejoin his regiment, which was assigned to the defenses of Washington and in Patterson’s Valley Campaign of 1861. During that campaign, he demonstrated a personality trait that cost him dearly two years later. “It is said when he was ordered, at Falling Waters, to proceed with a squadron in search of a militia regiment which had become detached from the army, that he never ceased during the entire movement, to express his opinion of militia in general and of the politicians who were responsible for the war,†duly recorded the historian of the 5th U. S. Cavalry.

Whiting then served in McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign of 1862. He led the 5th U.S. Cavalry in its ill-fated sabre charge against Confederate infantry at Gaines Mill in June 1862, and was captured when his horse was shot out from under him. An account of this charge reads: “Only the cavalry and a part of the artillery remained on this part of the field. A brigade of Texans, broken by their long advance, under the lead of the hardest fighter in all the Southern armies, come running on with wild yells, and they were a hundred yards from the guns. It was then that the cavalry commander ordered Capt. Charles J. Whiting, with his regiment to charge. No one had blundered; it was the supreme moment for cavalry, the opportunity that comes so seldom on the modern field of war, the test of discipline, hardihood and nerve. Right well was the task performed. The 220 troopers of the Fifth Cavalry struck Longstreet’s veterans squire in the face. Whiting, his horse killed under him, fell stunned at the foot of the Fourth Texas Infantry.â€

After spending a month in Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison, he was sent north to Washington under parole and then was exchanged for another captain and promoted to major. Whiting commanded the 5th U. S. Cavalry throughout the fall and winter of 1862-1863 and participated in the Maryland Campaign and also in the Battle of Fredericksburg, although the role of the cavalry was extremely limited in the great December battle. Whiting also led his regiment in the 1863 Stoneman Raid that occurred during the Chancellorsville Campaign.

Although he was one of the oldest serving officers in the Regular cavalry, Whiting assumed command of the Reserve Brigade in June 1863 when Buford took command of the 1st Division. His brigade consisted of the U.S. Army Regular cavalry units assigned to the Army of the Potomac, the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th U. S. Cavalry, and the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (also known as Rush’s Lancers). His tenure in brigade command was brief, lasting only a couple of weeks.

Whiting led the Reserve Brigade during the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. The major gave the 2nd U.S. Cavalry orders that conflicted with orders from Buford, and the Regulars failed to join in a charge to rescue the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which had charged all of the Confederate horse artillery near St. James Church, infuriating Buford. Shortly after Brandy Station, Whiting was relieved of his command and sent to the Draft Rendezvous at Fort Preble in Portland, Maine. Unexpectedly, while serving in Maine, Major Whiting was “dishonorably dismissed from the service on November 5, 1863 for disloyalty and for using contemptuous and disrespectful words against the President of the United States.â€

A letter found in Whiting’s pension file at the National Archives lends a great deal of insight into why he was cashiered. The letter states that Whiting’s hotel room in Portland faced the public square and had a balcony. “A mass meeting of Republicans was announced for a certain evening to take place, at which General [Benjamin F.] Butler was to speak. The local committee called upon the Major, as the story goes, and asked him if he had any objection to General Butler hopping through his room in order to address the gathering outside the balcony. The Major replied, ‘by no means,’ and peevishly added, permitted he could have time to ‘lock up his spoons.’ The Committee was incensed and informed General Butler and the Maj. was removed from the service.†Whiting returned to the family home in Castine to ponder his future.

After the end of the Civil War, the expanded Army had a real need for experienced officers to command troops on the western frontier. In May 1866, President Andrew Johnson reinstated Whiting to duty as Major of the 3rd Cavalry, with his records stating “the disability of holding a commission by reason of said dismissal was removed by the President of the United States.†Whiting assumed command of Fort Marcy in New Mexico. He then assumed command of Fort Union, New Mexico.

During July 1867, a party of Navajos at Bosque Redondo reservation, believed to have stolen livestock in their possession, fought back when troops attempted to recover the livestock. Six soldiers died in the exchange. Major Whiting led troopers of the 3rd Cavalry from Fort Union “to quell the present outbreak and prevent the occurrence of any future troubles with those Indians.†By the time Whiting arrived, the outbreak of violence had been quelled, and he and his troopers returned to Fort Union. Whiting later headed a board of officers that investigated the incident at Bosque Redondo, and he was appointed commander of Fort Sumner when the board determined that the former post commander had provoked the Indians.

In May 1869, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and transferred to the 6th Cavalry. He was assigned to command the Army post at Greenville, Texas, where his troopers were to keep the peace between feuding former Confederates and former Union soldiers.

In 1870, he took command of Fort Griffin in Abilene, Texas, which was responsible for protecting travelers from raiding Kiowas and Comanches. After five months there, he was transferred to the supernumerary list on December 15, 1870. On January 1, 1871, at the age of 56, he was honorably mustered out of the service. He packed his belongings and headed home to Castine. He and his wife lived out the rest of their lives there, supported by an Army pension. As he got older, the old injury to his back at Gaine’s Mill gave him more and more trouble and pain. After 20 years of peaceful retirement, Whiting died on New Year’s Day 1890 at the age of 75. He was buried in Castine.

Whiting spent nearly 30 years in the Regular Army, all in the mounted service. His service was honorable, and he was a good soldier who deserved a better fate than being cashiered from the Army. Here’s to Charles Jarvis Whiting, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filterI’ve added Corey Meyer’s interesting blog, The Blood of My Kindred, to the blogroll. Corey’s got some interesting insights, and is a fellow fighter in the neo-Confederate wars. Check it out.

Scridb filterI re-aggravated the pinched nerve in my neck again last week. It’s now been a week, and it’s finally beginning to settle down. I’ve been completely miserable and in a lot of intense pain, so I’ve been limiting my time on the computer to work, which is stuff I absolutely have to do. That’s why I haven’t posted anything since last week.

As it’s finally getting better (a number of Vicodin and three visits to the chiropractor later), I expect to resume regular posting tomorrow or Thursday at the latest.

Thanks for your patience.

Scridb filterFor the past few days, there has been a lot of discussion about the state and future of North & South magazine. It began with a post on Kevin Levin’s blog. After quite a few comments (including one by me), Ethan Rafuse pitched in. Ethan has put up two posts at the Civil Warriors group blog that also address the situation with North & South.

I think I can lend some insight. By way of introduction, I own a major block of voting stock in the company. I am in the top ten of the group of largest shareholders, and until two years ago, was a member of the company’s board of directors. I was kicked off the board by founder/editor/president Keith Poulter when he realized that I had turned hostile and would no longer approve his actions in managing the company without question. Consequently, I have some inside knowledge and insight that few others have.

The problems with this company run very deep and date back to its very beginnings. The simple truth is that the company has always been severely undercapitalized, from its very beginning. Poulter has always been very proud of the fact that he started the company on $15,000, which I can understand. That would be okay if he’d been able to take that $15,000 and turn it into a profitable operation, but it has never made a profit. In fact, the company has lost money every year of its existence.

There are a variety of reasons for that. First, and foremost, while he’s an excellent editor, Keith Poulter is an atrocious businessman. If North & South fails, it will be the second business of his to fail, the first being a wargaming company. He just has no idea how to run a successful and profitable business. The track record speaks for itself.

The biggest problem is that he and his ex-wife Kathy, who, conveniently enough, is the CFO of the company without the qualifications for the job, own enough stock to put down any attempts to depose them. I know this for a fact, because I tried. When I failed, that’s when I was kicked off the board in favor of the late Prof. John Y. Simon, who was willing to be a rubber stamp for Poulter. Since John’s death, that board position remains open and unfilled. There’s nobody to prevent Poulter from simply doing as he pleases. I’ve stopped caring, as I’ve accepted the sad reality that my investment is gone, pissed away by incompetent management.

Terry Johnston, the editor, and Joyce Gusner, the art director, were the only voices of reason, and were my allies. Terry, of course, was fired, and Joyce, sadly, died of breast cancer. Since Joyce’s unfortunate passing, all of the artwork and composition work is being done in China by people who obviously know nothing about the Civil War. Joyce had a large block of stock, but I’m not sure what happened to it. Terry had a few shares, but he was sent packing. When they dropped out of the picture, there truly was nothing to prevent Poulter from doing as he damn well pleases with the company without having to answer to anyone.

Further complicating things is that Keith Poulter spends the bulk of his time in China now. He’s never been good about communicating, and now that he’s spending most of his time there, forget getting a response from him. It’s very unprofessional, and it aggravates people to no end.

In fairness, the company’s wretched financial state has left Keith with no alternative but to serve as both editor as well as business manager. That’s a heavy burden, and it’s become clear that he’s not up to fulfilling both roles. The issues with publishing articles and things being in line for publication for years at a time are well documented in the posts and comments on the other blogs linked above. I have experienced the same problem myself–my article on the Battle of Tom’s Brook (the last thing of mine to be published in the magazine) sat in the production queue for the better part of three years before it finally saw the light of day, to my incredible frustration.

A friend of mine had an article in the last issue, and Poulter simply chopped off the conclusion without even asking him about it. Dan was absolutely flabbergasted when he saw the article in print without its conclusion, so much so that he wrote to Poulter to protest it. It took Poulter a while to respond to his e-mail, and when he did, he pretty much just blew Dan’s complaints and concerns off without even the courtesy of an explanation or an apology.

Among the financial problems is the elephant in the room. The last I knew, the magazine’s printer was owed in excess of $150,000 for back printing bills, and they may finally have finally said enough and pulled the plug. That debt has existed for pretty much the entire eleven year run of the magazine without much progress being made in whittling down the balance, and in these uncertain economic times, the printer may have finally determined that it could no longer carry this particular albatross around its neck. I certainly wouldn’t blame them if that’s the case.

Also, a couple of issues ago, the magazine lost its long-time cartographer, David Fuller, who was lured away to Civil War Times Illustrated, meaning that the last two issues were published without a single map. Given that superb maps were a hallmark of the magazine, it’s not a big surprise that the complete lack of any maps generated a lot of questions and complaints from readers. It’s very difficult to understand complicated military actions without maps, and the lack of maps really detracts from the quality of the magazine. Poulter then flagrantly lied about the situation in print in the magazine, directly contradicting the announcement that Dana Shoaf, the editor of CWTI, made in his magazine. It certainly made N & S look bad and made Keith look really petty.

Since Terry Johnston was fired, there have been a lot of complaints about the magazine’s content. Again, please see the comments and posts on the other blogs. Content has changed dramatically, and not necessarily for the best. In addition, there is a long-standing history of Poulter not paying authors timely, which has certainly hurt the magazine. Consequently, nobody really wants to write for him any more. I know of numerous authors who either haven’t been paid at all, or have been forced to wait for significant amounts of time to get paid. That has caused the stream of quality material to dry up.

So, to sum up, it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if the thing is swirling around the drain. Shame on me for not doing my due diligence and learning more about Poulter and his terrible track record before investing money into this cesspool. I’m paying the price by losing my investment. At least I’m not alone there.

As for North & South, it could have been great. Keith has a real gift for getting big name authors to clamor to write for him, and that’s how he was able to fill a brand-new publication with so much great content. But then he stopped paying authors, and his ego ran amok. The biggest shame is that it was all avoidable but for Keith Poulter’s ego.

Scridb filterThis post has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with the Civil War. I apologize to those of you who come here exclusively for the Civil War content since you will be disappointed by this post. However, I feel the need to rant about this.

Alex “A-Roid” Rodriguez at least fessed up and admitted that he had made abundant use of illegal anabolic steroids from 2001-2003, which included one of his MVP seasons and a year when he hit a career high 57 homers. All of this calls into question the validity of any of his statistics and taints his entire career. And this from the golden boy who was supposed to lead the Yankees back to the promised land. A-Fraud’s propensity for choking in the post season is already well known. I will be curious to see how he responds to hearing the chants of “A-Roid” from the faithful at Fenway Park. The worst part about it is that somewhere, Jose Canseco is snickering and saying “I told you so,” for he’s been saying for several years that A-Roid was a juicer.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but doesn’t that now make four major juicers from the recent editions of the New York Yankees: Jason Giambi, Roger Clemens, Andy Pettite, and now A-Roid? As if the Steinbrenner family has not done the game irreparable harm already, isn’t their real legacy now paying ridiculous salaries to juicers? There is simply no excuse and no justification for it or for them.

Is there any better possible reason for the imposition of a salary cap in major league baseball than what has happened this off-season with the Yankees? First, in a year when the economy is in the toilet, they spend $400 million on three free agents. And now, their golden boy–the guy with the largest contract in the history of baseball–has proved himself to be just another useless juicer.

It’s time that the rest of baseball impose a salary cap and rein in the Steinbrenners. Perhaps that way, some of the tremendous damage that they have done to the game might be undone.

I also believe that if Commissioner Selig had any cojones, he would declare that any player found to have cheated by using steroids is forever ineligible for admission to the Hall of Fame. That’s the best way I can think of to send a message to a guy like A-Roid, who desperately yearns for love and recognition, that cheating and juicing carries a large penalty. But Selig doesn’t have the stones to do it, meaning that guys like Barry Bonds, Rafael Palmiero, and now A-Roid will get into the Hall of Fame even though they cheated to get there. That’s not a good message to send kids, is it?

Scridb filterIt’s been quite a while since I’ve posted a sketch of a forgotten cavalryman, so I’ve decided to pay tribute to one today.

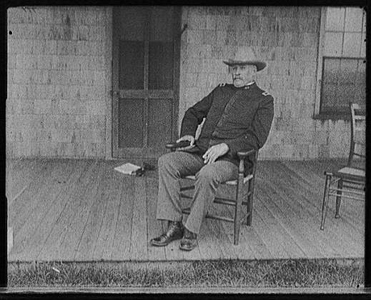

Samuel Baldwin Marks Young was born on January 9, 1840 at Forest Grove, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. His father, John Young, was of English descent as was his mother, Hannah (Scott) Young. His spent his early years upon the farm and at Jefferson College (now Washington & Jefferson) in Washington, PA, where he studied civil engineering. He married Margaret McFadden in 1861.

Samuel Baldwin Marks Young was born on January 9, 1840 at Forest Grove, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. His father, John Young, was of English descent as was his mother, Hannah (Scott) Young. His spent his early years upon the farm and at Jefferson College (now Washington & Jefferson) in Washington, PA, where he studied civil engineering. He married Margaret McFadden in 1861.

With the coming of the Civil War, he enlisted in the 12th United States Infantry as a private in April, 1861, and was made Corporal in the following June. On September 6, 1861, he was commissioned a captain in the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

He participated in heavy fighting during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, demonstrating great bravery and good leadership skills. He led the famous charge of one squadron of his regiment, and one section of Tidball’s horse artillery under Lieutenant Dennison, across the Stone Bridge on the left center of the line, in the Battle of Antietam. The defense of those guns led to the death of his regimental commander, Col. James Childs. In the wake of the death of Childs, and Young’s valor at Antietam, he was promoted to major. In November, 1862, while leading two squadrons of the 4th Pennsylvania, he attacked the rear of J. E. B. Stuart’s column at Jeffersonville, Virginia, and dismounted two guns, destroying the carriages before the supports arrived.

In the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville Campaigns, the 4th Pennsylvania served under the command of Brig. Gen. William Woods Averell, and experienced little hard fighting, although he did participate in the May 1863 Stoneman Raid. During the Gettysburg Campaign, he fought in the battles at Aldie and Upperville, where Major Young led his battalion in repeated charges with the steadiness and determination of a veteran officer. Moving on the right flank of the Army of the Potomac, the 4th Pennsylvania stretched away in its course to the Susquehanna River, arriving at Wrightsville just after the destruction of the Columbia bridge. Hastening back, the 4th Pennsylvania moved to a position on the left flank of the Army of the Potomac late in the morning of July 2, 1863. The regiment did not participate in the fighting on East Cavalry Field, and played a limited role in the pursuit of Lee’s army after Gettysburg.

On October 12, when Lee attempted his flank movement during the Bristoe Campaign, the 4th was sent to the relief of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which, while on picket duty near Jeffersonville, on the right bank of the Rappahannock and opposite White Sulphur Springs, was attacked and hard pressed by the advancing enemy. The two regiments made a stand and fought bravely in a hopeless situation. The Confederate infantry flanked the horse soldiers from their position, capturing many and inflicting a large number of casualties upon both regiments. Major Young was conspicuous for his valor, and in the heat of the engagement was struck in the right elbow by a Minie ball, inflicting a painful and serious wound. After six months of intense suffering, the arm was saved, but the joint was left permanently stiff.

In an action on July 20, 1864, this arm was again hit, breaking both bones of the forearm. He recovered and soon re-joined his regiment in the field. In the spring of 1865, the same arm was struck a third time, but Young recovered and did not lose the arm.

In October 1864, Major Young was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and in December, to Colonel, and he assumed command of a brigade of cavalry. At the battle of Hatcher’s Run in February 1865, Colonel Young was ordered to charge with his brigade after an unsuccessful attack by an infantry brigade. He carried out his orders and carried an entrenched line with his charge. Gen. David M. Gregg complimented Colonel Young for his heroic action in front of the entire 2nd Cavalry Division. Confederate General John Pegram was killed in this encounter.

Colonel Young was active throughout the retreat and pursuit of Lee’s army from Five Forks to the surrender to the surrender at Apommattox, in which the movements were remarkable for rapidity and skill. He led a charge of his brigade even after the surrender had been consummated, though not known upon the front, routing a rebel brigade and capturing its colors. He was brevetted brigadier general of volunteers for this action.

At the conclusion of the war, he was appointed to a lucrative position in the Revenue Department of the U. S. government, but refusing to sacrifice his principles to party purposes, he was removed by President Johnson.

He was soon after appointed second lieutenant in his old regiment, the 12th U. S. Infantry. When the army was reorganized in July 1866, he was commissioned a Captain in the 8th U. S. Cavalry, and enjoyed remarkable success in the various campaigns against hostile Indians in Arizona and New Mexico. He was promoted to major of the 3rd U. S. Cavalry on April 2, 1883 and to lieutenant colonel of the 3rd U. S. Cavalry on August 16, 1892. After a brief stint as acting superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, he was promoted to colonel of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry on June 19, 1897.

With the commencement of the war with Spain in 1898, he was commissioned brigadier general of volunteers, and was then promoted to major general of volunteers in July 1898, commanding a division in Cuba during the Santiago Campaign.

During the Philippine Insurrection, he returned to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers and commanded brigades in the Northern Luzon District, including serving as military governor of the District. He was commissioned brigadier general in the Regular Army on January 2, 1900, and major general on February 2, 1901.

From February 1901 to March 1902, Young commanded the Military District of California from the Presidio in San Francisco. In 1901, his daughter Marjorie married an army surgeon was a nephew of Young’s old comrade in arms, General John Gibbon. He then served as the first president of the Army War College between 1902 and 1903. Then, under the newly-implemented General Staff System, he was promoted to lieutenant general and was appointed to serve as the U. S. Army’s first Chief of Staff in August 1903. He held this position until he retired as a result of age in January 1904.

He served as Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park 1907-1908. In 1909-1910, he served as president of a Board of Inquiry that investigated the riot of black soldiers of the 25th U. S. Infantry at Brownsville, TX on August 13, 1906, and affirmed the subsequent dishonorable discharge of 159 soldiers by order of President Theodore Roosevelt. He then served as governor of the Soldier’s Home in Washington from 1910 to 1920. He then enjoyed a quiet retirement after more than 60 years of public service.

His wife Margaret died in 1892, and he married Mrs. Annie Dean Huntley of Chicago in 1908. Samuel and Margaret Young had six children. His son, Ranald MacKenzie Young, died at the age of two. His daughters all survived him. Two of his daughters married cavalry officers who attained flag rank.

General Young died at his house in Helena, MT on September 1, 1924, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery after a state funeral. Thus ended the life of a remarkable soldier who rose from private to chief of staff of the United States Army. Here’s to Samuel B. M. Young, forgotten cavalryman.

Scridb filterHere’s an article that gives you a sense of the ridiculous budgetary constraints that the Ohio Historical Society is forced to endure. Whenever the Ohio General Assembly needs to save money, the OHS budget is inevitably the first place they look. And this is the result:

Recession Forces Historians to Make Do

By James Hannah, Associated Press2/1/2009

Associated Press

http://www.newarkadvocate.com/article/20090201/NEWS01/902010332COLUMBUS — The Civil War flag that was brandished by the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry is wrapped tightly around its pole. It’s a delicate task to unfurl the almost 150-year-old banner without it crumbling.

Yet, the humidity-raising chamber used to loosen the material consists of a homemade aluminum frame covered with a plastic-like film. It was built with parts from Lowe’s that cost less than $500. The work is being done in a warehouse and in a homemade chamber instead of with state-of-the-art equipment costing as much as $20,000.

With the recession tightening its grip, budgets being cut and donors drying up, preservationists are scaling back on restorations.

In Missouri, efforts to buy well-known works by home-state artists have been cut back. A fundraising campaign to help preserve Native American art in Montana is grinding to a standstill.

Money still is being given for conservation but not at the levels that are necessary, said Eryl Wentworth, executive director of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works.

“It’s so distressing to me because it’s shortsighted,” she said. “We lose our history. We lose a portion of our culture, our memory.”

Authorities estimate 4.8 billion artifacts are in U.S. archives, libraries, museums and historical societies, but one in four institutions have no controls to protect against temperature, humidity and light.

According to a 2005 survey by Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, 13.5 million historic objects, 153 million photographs and 4.7 million works of art needed immediate care.

Lawrence Reger, president of Heritage Preservation, said publicity about the survey generated increased support for the care of collections so they are available for future generations.

“Unfortunately, the current recession has all but brought this to a standstill,” Reger said.

The Ohio Historical Society is trying to preserve much of the Ohio Adjutant General’s battle flag collection — 552 flags carried in five wars. Most earlier preservation was carried out in the 1960s and to date, only 18 flags have been preserved using updated, more costly techniques paid for largely by private funds.

Soldiers who hoisted Civil War flags in battle were fat targets for the enemy.

“Men knew it was very likely they were going to die when they were carrying them,” said James Strider, the society’s director of historic preservation.

Historical societies and museums around the country are being squeezed.

A state budget deficit of $4 billion in Illinois cost the Historic Preservation Agency a conservator and curator who were instrumental in prioritizing artifacts that need to be conserved. They include a three-wheeled wood and leather baby buggy that belonged to David Davis, who was appointed by Abraham Lincoln to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“There are literally hundreds of items in our collections at any particular moment that need repair or conservation, and without staffing the list will continue to grow,” said spokesman David Blanchette.

The State Historical Society of Missouri has backed away from an aggressive plan to buy paintings of famous Missouri artists Thomas Hart Benton and George Caleb Bingham. It risks losing the artwork to other buyers.

“It’s extremely challenging to try to raise money when virtually everybody is impacted in some way by the recession,” said Gary Kremer, the society’s executive director.

The Yellowstone Art Museum, home to historic American paintings as well as modernist and abstract expressionist art, has been trying to raise money for more than two years to build a preservation facility. About $1.8 million of a required $2.8 million has been collected.

Robyn G. Peterson, executive director of the Billings, Mont., museum, said the museum has no funds in its annual $1 million budget for preservation. Many artworks, such as Plains Indian beadwork, are being stored in a vault that is “full to bursting.”

Pete Sepp, spokesman for the National Taxpayers Union, said historic preservation has to be subject to budget priorities.

“Preserving the past is important, but if governments don’t start spending and borrowing less, there won’t be much of a future left for our kids to enjoy,” Sepp said.

The Ohio Historical Society has seen its budget shrink by 13 percent in the past eight years. The society has laid off its preservation staff.

With all of its storage space filled and no money to expand, the society is going through its collections to decide what not to keep. It virtually has stopped accepting donations of artifacts.

Many of the society’s artifacts are stored in warehouses without adequate climate and pest control. The warehouses sit about a mile from the historical center where artifacts are displayed. Moving collections back and forth risks damaging them.

Mark Hudson, executive director of the Historical Society of Frederick County (Md.), said when public and private funding shrinks, museums and historical societies often focus on exhibits that draw paying patrons.

“When you’re faced with having to pay electric bills or laying off staff, things like conservation treatments can take the back seat very quickly,” Hudson said.

I realize that we’re dealing with difficult economic times, and I realize that governmental funds are scarce. However, just once, I would like to see the budget trimmed somewhere else…..

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like