Yesterday was the 152nd anniversary of the Battle of Morton’s Ford, fought on February 6, 1864. I had wanted to get something posted yesterday, but I was presenting at a symposium and then had a 7.5 hour drive today to get home. So, unfortunately, this is a day late. Let’s hope it’s not a dollar short. 🙂

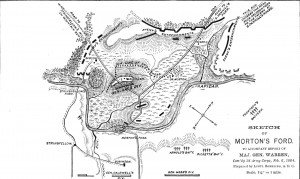

For a larger view of this map, please click on it.

For a larger view of this map, please click on it.

“A Curious Affair:” The Battle of Morton’s Ford, February 6, 1864 Proceeding south on Batna Road (Rt. 663), one observes an isolated hillock to the west. Called “Stony Point” in the Civil War, this knoll was home during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac to 2,000 soldiers of the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division of the 2nd Army Corps. In early February 1864, little did these peacefully reposed troops realize they would soon help initiate one of the strangest and least known of all military actions occurring in and about Culpeper County.

In order to support a planned cavalry-infantry raid on Richmond, Union strategists in Washington instructed the Army of the Potomac to initiate a diversionary attack against entrenched Confederates south of the Rapidan. Although stoutly opposed to the impending assault against the enemy’s “strongly entrenched line,” Federal commander Gen. John Sedgwick selected Morton’s Ford as the avenue of attack.

On the morning of February 6, 8,000 soldiers of the 3rd Division secretly amassed north of Stony Point. Once his ranks were formed, Gen. Alexander Hays ordered his division to move out quickly toward Morton’s Ford, located just over a mile south. As it turned out, this stealthy advance would be the only positive thing the Yankees accomplished for the remainder of a

long and bloody day.Crossing in front of Powhatan Robinson’s house, Struan, the 3rd Division rushed toward Morton’s Ford. Near the head of the assaulting force rode General Hays, who “had added two or three extra fingers to his morning dram.” Actually, this was a polite way of revealing that General Hays was stone drunk. As his advancing soldiers leaped into the icy river, General Hays followed closely behind swinging an ax high over his head at tree branches while shouting, ‘We will cast then down as I do this brush!”

Ignoring Rebel musket fire, Hays’ men dived for cover to escape their “reckless and incoherent” commander’s wildly heaving blade. With inebriated leadership at the fore, the dubious operation kicked off. Over on the Southern side, one artillerist described a “rather sudden transition from peace to war.” Undaunted, the famed Richmond Howitzers opened up on the Yankees now pouring across the river. Riding up quickly, Gen. Richard Ewell asked in amazement, “What on earth is the matter here?” Convinced his corps was under attack, General Ewell focused the plunging fire of his big command on the soon outnumbered attackers. “We crossed the river to feel the enemy, “one bluecoat wrote, “and we got the feel badly.” Another Yank pointed out the obvious, “The enemy was not badly scared.” Under direct fire from Rebel works located a mile back of the ford, the courageous but poorly led Federals withered and their “attack” ground to a halt. One Federal officer theorized the “purpose of our attack was to draw a force of enemy to our front.” The Federals achieved that objective as the cool Southerners responded “in a deadly focus of fire.” Northerners fell dead by the dozens.Late in the day, things only got worse for the besieged Federals as the Confederates initiated a bold counterattack. One Union officer—obviously a future politician—artfully described this Rebel thrust as the “enemy retreating toward us.” Disingenuous semantics aside, the Yankees withdrew after dark over the river, losing near 300 casualties in the process while Dick Ewell’s corps incurred about 55 casualties. R.E. Lee’s great biographer accurately termed the daylong battle a “curious affair.” And also stupid in the extreme, one might offer, as this pointless action accomplished nothing but death and misery.

Following the battle, General Sedgwick complained bitterly that Washington authorities should not have initiated orders resulting in the disastrous Battle of Morton’s Ford. But with General Sedgwick’s castigations of higher-ups noted, this debacle on the Rapidan would not represent the last time American warriors entered a battle with an ill-defined mission, while engaged in an action counseled against by generals in the field, and also fighting in a locale wherein they were not wanted to begin with.

This is what Morton’s Ford looks like as of last week.

This is what Morton’s Ford looks like as of last week.

This is what Struan looks like today.

This is what Struan looks like today.

Both photos are by Clark B. Hall.

The Battle of Morton’s Ford, although a small engagement in terms of numbers involved, was an important engagement that had strategic implications for the coming campaign seasons, and which was remembered by the soldiers who fought there. Let’s remember their sacrifices there. Hopefully, some or all of this pristine battlefield will be preserved some day.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Comments

Comments are closed.