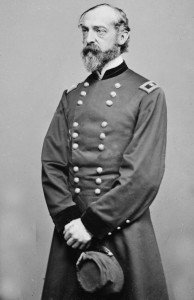

In part one of this two-part series, we examined the content of the Pipe Creek Circular, and we also looked at the Pipe Creek Line itself. In this, the second part, we will examine the controversy created by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s handling of the Pipe Creek Circular. Specifically, we will examine its role in the controversy that Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles stirred up to deflect attention away from his own conduct at Gettysburg. To recap briefly, Meade had the Army of the Potomac’s engineers lay out a very strong defensive position along Parr Ridge, a dominant east-west ridge that paralleled Big Pipe Creek in Maryland between Manchester and Middleburg, which is south and west of Taneytown. The reality is that this position was even more commanding than the position held by the Army of the Northern Virginia on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg the previous winter, and it was easily defending. Had the Army of the Potomac taken up a position there, it is very unlikely that Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army could have driven the blueclad soldiers off of it unless they somehow managed to outflank the position.

At the same time, Meade did not make the final decision to stand at Gettysburg until his council of war on the night of July 2. Earlier that day, Sickles disobeyed a direct order and advanced his Third Corps from its intended position on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge to a prominent plateau along the Emmitsburg Road near the Joseph Sherfy peach orchard. Sickles did not like his assigned position and decided to make the move on his own initiative. Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, the commander of the Second Corps, which was next in line next to Sickles’ Third Corps, watched the movement and said, “Wait a moment–you will soon see them tumbling back.” Unfortunately, Hancock was correct. Meade tried to countermand the movement, but it was too late. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps was about to launch its determined assault up the Emmitsburg Road.

As an initial note, it seems quite obvious that Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, commander of the Army of the Potomac’s left wing, did not receive the Pipe Creek Circular before he was killed at approximately 9:15 a.m. on July 1, 1863. Reynolds came to Gettysburg to reinforce Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division and was killed while placing troops of the Iron Brigade in position. Unfettered by the strictures of the Pipe Creek Circular, Reynolds made the critical decision to commit the army’s left wing to the fight at Gettysburg. Reynolds was killed early in the action, but his First Corps and Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard’s Eleventh Corps committed to the fighting there. The Third Corps and Twelfth Corps arrived that night, meaning that all but the Second, Fifth, and Sixth Corps were on the field that night.

In the interim, Meade sent Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock to Gettysburg to ascertain whether Gettysburg was the right place for the Army of the Potomac to make its stand. Hancock further validated Reynolds’ decision and reported to Meade the Army of the Potomac held a strong defensive position. Meade then rode to the battlefield himself, arriving late in the evening. However, and as pointed out in the first post of this series, the decision to stand and fight at Gettysburg was not finalized until Meade’s council of war on the night of July 2. Up until then, the possibility of a retreat to the Pipe Creek Line remained a very real possibility.

Thanks to meddling by the Radical Republicans in Congress, that possible retreat became the subject of a series of Congressional hearings during the winter of 1863-1864. The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, headed by Radical Republican Sen. Benjamin Wade of Ohio, sought to prod President Abraham Lincoln into pursuing more aggressive war policies against the Confederacy, and it sought to crucify George Meade for allowing Lee’s army to escape across the Potomac River in the wake of its defeat at Gettysburg.

The Joint Committee held a series of hearings during the winter of 1864, where Sickles accused Meade of mismanaging the Battle of Gettysburg, planning to retreat from Gettysburg prior to the Union victory there, and failing to pursue and defeat the Army of Northern Virginia north of the Potomac River. Sickles, a former Congressman and the leader of Tammany Hall, was determined to deflect criticism from his own controversial role at Gettysburg, where he intentionally disobeyed Meade’s orders and nearly caused the destruction of the Third Corps in the process.

After an exhaustive investigation reminiscent of the repeated Congressional inquiries into the death of an American ambassador at Benghazi, Libya, the Joint Committee ultimately found no evidence to support Sickles’ claims. However, Wade, determined to make the Lincoln Administration look bad, nevertheless spun the results to paint Meade in the most negative light possible.

Wade’s report indicated:

General Meade, however, decided upon making a stand at another point for the purpose of receiving the attack of the enemy, and selected a position the general line of which was Pipe Creek, the left resting in the neighborhood of Middleburg, and the right at Manchester, and even down to somewhat late in the day of the 1st of July was engaged in making arrangements for occupying that position as soon as the movements of the enemy should indicate the time for doing so. To that end, on the morning of the 1st of July, a preliminary circular was issued, directing his corps commanders to make the necessary preparations for carrying the order into effect as soon as circumstances should arise to render it necessary or advisable in the opinion of the commanding general; and it was not until information reached General Meade, in the afternoon of July 1, that the cavalry, under General Buford, had come in contact with a large force of the enemy near Gettysburg, and that General Reynolds, who had gone to his assistance with the 1st and 11th corps, had been killed, that the attention of General Meade seems to have been seriously directed to the position at Gettysburg for meeting the enemy. He sent General Hancock there to report the condition of our troops and the character of the ground. General Meade says that before he received the report of General Hancock he had decided, upon information received from officers from the scene of action, to concentrate the army at Gettysburg, and it was done that night and the next day, and the battle was there fought.

At least that much of the report finds that Meade acted prudently and appropriately. However, Wade was far from finished with the commander of the Army of the Potomac.

The report, biased as it was, relied on the testimony of three officers, including Sickles and the Army of the Potomac’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield (a close ally and friend of Meade’s predecessor, Joseph Hooker, who despised Meade and whom Meade despised in turn), who claimed that Meade had wanted to retreat from Gettysburg on July 2 and that only the onset of Longstreet’s attack prevented him from doing so. However, six officers, including Meade himself, claimed strongly that such was not the case. Meade’s own statements before the Joint Committee on this subject are particularly enlightening:

I have understood that an idea has prevailed that I intended an order should be issued on the morning of the 2d of July, requiring the withdrawal of the army, or the or the retreat of the army from Gettysburg, which order was not issued owing simply to the attack of the enemy having prevented it.

In reply to that, I have only to say that I have no recollection of ever having directed such an order to be issued, or ever having contemplated the issuing of such an order, and that it does seem to me that any intelligent mind who is made acquainted with the great exertions I made to mass my army at Gettysburg on the night of July 1, it must appear entirely incomprehensible that I should order it to retreat after collecting all my army there, before the enemy had done anything to require me to make a movement of any kind.

Meade returned on another occasion to give an additional statement, demonstrating remarkable restraint in the process (which, for a man with a well-known temper, had to have been a challenge):

I wanted to say a few words to the committee, in extension of the remarks which I made the last time I was here, in reference to a charge which I expected then would be made against me, and which I understand has since been made against me, to the effect that I intended that an order should be issued, on the morning of July 2, withdrawing the army from the position it then occupied at Gettysburg, and retreating, before the enemy had done anything to require me to withdraw.

It is proper that I should say that the fact of such a charge having been made here, or such a report given here, has reached me through outside sources, but in such a way that I can hardly disbelieve that such a statement has been made; and that it was made by an officer who occupied a very high and confidential position on my staff, the chief of staff. Major General Butterfield. Now, indulging in the utmost charity towards General Butterfield, and believing that he is sincere in what he says, I want to explain how it is possible that such an extraordinary idea could have got into his head.

I utterly deny, under the full solemnity and sanctity of my oath, and in the firm conviction that the day will come when the secrets of all men shall be made known — I utterly deny ever having intended or thought, for one instant, to withdraw that army, unless the military contingencies, which the future should develop during the course of the day, might render it a matter of necessity that the army should he withdrawn. I base this denial not only upon my own assertion and my own veracity, but I shall also show to the committee, from documentary evidence, the dispatches and orders issued by me at different periods during that day, that if I did intend any such operation I was at the same time doing things totally inconsistent with any such intention.

I shall also ask the committee to call before them certain other officers of my staff, whose positions were as near and confidential to me as that of General Butterfield, who, if I had had any such intention, or had given any such orders as he said I gave, would have been parties to it, would have known it, and have made arrangements in consequence thereof; all of whom, I am perfectly confident, will say they never heard of any such thing. I refer to General Hunt, chief of artillery, and who had artillery occupying a space of from four to five miles, drawn out on the road, and who, if I had intended to have withdrawn that army, should have been told to get his trains out of the way the very first thing, because the troops could not move until the artillery moved. I would also ask you to call upon General Ingalls, my chief quartermaster, who had charge of the trains. Also General Warren, my chief engineer, who will tell you that he was with me the whole of that day, in” constant intercourse and communication with me; and that instead of intending to withdraw my army I was talking about other matters. All these officers will corroborate what I say, that I never mentioned any such purpose to any of them.

General Butterfield remained at Taneytown on the night of the 1st July, and did not join me on the field until about 9 or 10 o’clock in the morning of the 2d, I having arrive 1 there at one o’clock. Soon after he arrived I did direct him to familiarize himself with the topography of the ground; and directed him to send out staff officers to learn all the roads. As I have already mentioned, in my previous testimony here, I had never before been at Gettysburg, and did not know how many roads ran from our position, or in what directions they ran. My orders to General Butterfield were similar to this:

“General Butterfield, neither I nor any man can tell what the results of this day’s operations may be. It is our duty to be prepared for every contingency, and I wish you to send out staff officers to learn all the roads that lead from this place; ascertain the positions of the corps; where their trains are; prepare to familiarize yourself with these details, so that in the event of any contingency you can, without any order, be ready to meet it.”

It was in anticipation of possible contingencies, and not at all that I had made up my mind to do anything of that kind.

I would furthermore call the attention of the committee to the absurdity of such an idea. If I had directed the order to be issued, why was it not issued? With General Butterfield’s capacity it would not have taken him more than ten or fifteen minutes to prepare such an order. We were furnished with what you call manifold letter-writers; so that, after the framework of an order is prepared, ten or a dozen copies may be made at once. Why was not the order issued; or if issued, why was it not executed? There was no obstacle to my withdrawing that army if I had desired. The enemy presented none. There was not a moment from the time the first gun was fired at Gettysburg, until we knew the enemy had retired, that I could not have withdrawn my army; therefore, if I had entertained such an idea, it seems to me extraordinary that I did not execute it.

That General Butterfield may have misapprehended what I said to him, that he may himself have deemed a retreat necessary, and thought we would be compelled to retreat in the course of the day, and in the excess of zeal, and desire to do more than he was called upon to do, may have drawn up an order of that kind, I do not deny; but I say he never showed me any such order, and it had not my sanction nor authority.

Reluctantly, Wade was forced to find that there was insufficient evidence to support the claims that Meade had ordered the Army of the Potomac to retreat from the battlefield at Gettysburg. However, the damage had been done. Meade’s credibility and authority as the commander of the Army of the Potomac had been badly undermined. There are plenty of lessons to be learned here, especially by modern politicians determined to use Congressional resources to pursue their own political agendas and witch hunts.

The Joint Committee, however, was not finished with George Meade. In another upcoming series, we will examine the allegations that Meade mismanaged the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia during the retreat from Gettysburg.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Eric: Excellent stuff. Looking forward to Part III.

Allan Guelzo in his book really supports the view that Meade wanted to retreat until the last moment of the

battl. Trudeau felt that Meade acted appropriately at

all times. I agree with Trudeau and furthermore, as

many do that Meade was treated shabbily after the battle.

For a man who had been in command only 3 days before the battle, that his performance was superb in that he

was concerned more with his responsibilities than with

his image. At at a remove of 152 years he remains, with

Grant and Sherman an excellent commander.

That’s just one of the many things that I really hate about Guelzo’s character assassination of Meade, Edward. That book pisses me off for that reason.

Read the series on the retreat. The first three parts are already up, with three more to go.

I agree with Eric. It’s too easy, and too attractive for too many people, to seek controversy whether it was there or not. Meade being prepared for contingencies is not at all the same as Meade wanting to retreat or ordering a retreat. It’s surprising that Guelzo, an army brat himself, would assert such a calumny, which could be made on the same grounds against his dad, or my dad, or any officer who has ever commanded troops. Maybe Gettysburg studies have indeed reached the point of diminishing returns when we return to this manufactured controversy. Instead, we should lay to rest,as Eric does here, any notion that Sickles had any justification for disobeying his clear orders and moving forward with, as far as I can tell, no recon of any point of his new line (which was not a continuous line) except for the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Pike plateau.