A gentleman named Ira Shaffer contacted me today and invited me to become a member of the board of trustees of the Friends of the Alligator. Mr. Shaffer has an illustrious ancestor, Marshal Joachim Murat, perhaps the greatest of all cavalrymen. I was very pleased to accept the offer, and thought it might be nice to post some information about the Alligator.

A gentleman named Ira Shaffer contacted me today and invited me to become a member of the board of trustees of the Friends of the Alligator. Mr. Shaffer has an illustrious ancestor, Marshal Joachim Murat, perhaps the greatest of all cavalrymen. I was very pleased to accept the offer, and thought it might be nice to post some information about the Alligator.

From The Dictionary of American Fighting Ships:

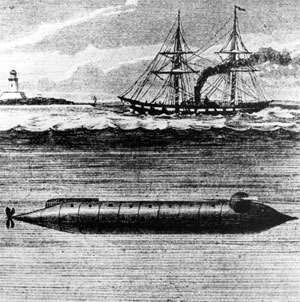

The creation of French inventor, Brutus De Villeroi. Whether a deliberate publicity stunt or not, DeVilleroi succeeded in convincing the Union Navy that he could produce a submersible warship from which a diver could place an explosive charge under an enemy ship. Six months later, in November 1861, he was under contract to build the Union’s first submarine, Alligator.

Built in Philadelphia, the 47-foot long Alligator was primarily intended to counter the threat of the Confederate ironclad, the Virginia. Although the Navy specified that the submarine’s construction take no more than 40 days at a cost of $14,000, the project suffered long delays. As project supervisor, DeVilleroi objected to changes in certain aspects of his plans for the vessel’s construction. In response, he effectively exited himself from the process and was later officially dismissed as supervisor.

About a month after its launch on May 1,1862, the oar-propelled submarine was towed to Hampton Roads, Virginia. Her first missions: to destroy a strategically important bridge across the Appomattox River and to clear away obstructions in the James River.

When the Alligator arrived at the James River, with civilian Samuel Eakins in charge, a fierce battle was being waged in the area. Because neither the James nor the Appomattox was deep enough to permit the vessel to submerge, it was feared that even a partially visible submarine would be vulnerable to seizure by the Confederates. The Alligator was sent to the Washington Navy Yard, for further experimentation and testing.

In August 1862, Lt. Thomas O. Selfridge accepted command of the submarine, after being promised promotion to captain if he and the Alligator’s new crew destroyed the new Confederate ironclad, the Virginia II. During test runs in the Potomac, the Alligator proved to be underpowered and unwieldy. During one particular trial, the sub’s air quickly grew foul, the crew panicked, and all tried to get out of the same hatch at the same time–prompting Selfridge to call the whole enterprise “a failure.†He and his crew were reassigned and the vessel was sent to dry dock for extensive conversion. The dream of using this “secret weapon†against the Virginia II was scrapped.

Over the next six months, the Alligator’s system of oars was replaced by a screw propeller. In early spring 1863, President Lincoln observed a demonstration of the “improved†vessel. Shortly thereafter, RADM Samuel Dupont ordered the Alligator, once again commanded by Eakins, to participate in the capture of Charleston.

Towed by the USS Sumpter, the unmanned Alligator left Washington for Port Royal on March 31, 1863. On April 2nd, a fierce storm forced the crew of the endangered Sumpter to cut the submarine adrift, somewhere off the Cape Hatteras coast. According to reports sent to Secretary of the Navy Welles, the Alligator was “lost” at sea.

Specifications: She was said to be about 30′ long and 6′ or 8′ in diameter. “It was made of iron, with the upper part pierced for small circular plates of glass, for light, and in it were several water tight compartments.” It had originally been fitted with sixteen paddles protruding from the sides to be worked by men inside, but on July 3, 1862, she was ordered to Washington Navy Yard to have her folding oars replaced by a propeller which was powered by a hand crank. It was said to be capable of seven knots. “The Alligator was to have been manned by sixteen men, besides one in submarine armor, who was the explorer, and a captain who was to steer the craft. An air pump in the center of the machine, to which were attached two air tubes, attached to floats, was to furnish air to the occupants, the machine being of course air tight. The entrance to it was through a man-hole at one end, which was covered with an iron plate, with leather packing.” She was to have been submerged by the flooding of compartments. The Alligator was also described as a “semi-submarine boat,” 46′ (or 47′) long and 4’6″ in diameter, with a crew of seventeen.

In other words, she was the Union’s version of the Hunley. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is conducting the search for the Alligator, which searsh goes on. NOAA plans to raise her and put her on display just as the Hunley was raised and put on display. NOAA has a very informative web site dedicated to its effort to locate the Alligator.

The Friends of the Alligator intend to construct and house a full-scale working replica of the Alligator as a major Civil War tourism attraction in the greater Philadelphia metro area (where she was built) – as well as to conduct symposia and educational opportunities to the membership. I’m honored to have been asked to assist in bringing a major Civil War attraction to my home town of Philadelphia.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Comments

Comments are closed.