No battle of the American Civil War has generated more ongoing and enduring controversies than the Battle of Gettysburg. With the anniversary of the battle looming once more, I wanted to address one of the more heated and oldest controversies of the battle, the Pipe Creek Circular and how it impacted the outcome of the battle. This two-part series will address the Pipe Creek Circular and its implications for the Army of the Potomac.

On June 30, 1863, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, who had only been in command of the Army of the Potomac for less than 48 hours, issued the following circular to his corps commanders:

CIRCULAR

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Taneytown, July 1, 1863.

From information received, the commanding general is satisfied that the object of the movement of the army in this direction has been accomplished, viz, the relief of Harrisburg, and the prevention of the enemy’s intended invasion of Philadelphia, &c., beyond the Susquehanna. It is no longer his intention to assume the offensive until the enemy’s movements or position should render such an operation certain of success.

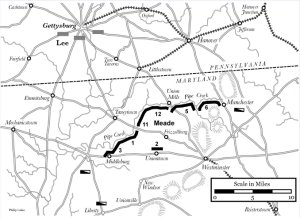

If the enemy assume the offensive, and attack, it is his intention, after holding them in check sufficiently long, to withdraw the trains and other impedimenta; to Withdraw the army from its present position, and form line of battle with the left resting in the neighborhood of Middleburg, and the right at Manchester, the general direction being that of Pipe Creek. For this purpose, General Reynolds, in command of the left, will withdraw the force at present at Gettysburg, two corps by the road to Taneytown and Westminster, and, after crossing Pipe Creek, deploy toward Middleburg. The corps at Emmitsburg will be withdrawn, via Mechanicsville, to Middleburg, or, if a more direct route can be found leaving Taneytown to their left, to withdraw direct to Middleburg.

General Slocum will assume command of the two corps at Hanover and Two Taverns, and withdraw them, via Union Mills, deploying one to the right and one to the left, after crossing Pipe Creek, connecting on the left with General Reynolds, and communicating his right to General Sedgwick at Manchester, who will connect with him and form the right.

The time for falling back can only be developed by circumstances. Whenever such circumstances arise as would seem to indicate the necessity for falling back and assuming this general line indicated, notice of such movement will be at once communicated to these headquarters and to all adjoining corps commanders.

The Second Corps now at Taneytown will be held in reserve in the vicinity of Uniontown and Frizellburg, to be thrown to the point of strongest attack, should the enemy make it. In the event of these movements being necessary, the trains and impedimenta will all be sent to the rear of Westminster.

Corps commanders, with their officers commanding artillery and the divisions, should make themselves thoroughly familiar with the country indicated, all the roads and positions, so that no possible confusion can ensue, and that the movement, if made, be done with good order, precision, and care, without loss or any detriment to the morale of the troops.

The commanders of corps are requested to communicate at once the nature of their present positions, and their ability to hold them in case of any sudden attack at any point by the enemy.

This order is communicated, that a general plan, perfectly understood by all, may be had for receiving attack, if made in strong force, upon any portion of our present position.

Developments may cause the commanding general to assume the offensive from his present positions.

The Artillery Reserve will, in the event of the general movement indicated, move to the rear of Frizellburg, and be placed in position, or sent to corps, as circumstances may require, under the general supervision of the chief of artillery.

The chief quartermaster will, in case of the general movement indicated, give directions for the orderly and proper position of the trains in rear of Westminster.

All the trains will keep well to the right of the road in moving, and, in case of any accident requiring a halt, the team must be hauled out of the line, and not delay the movements.

The trains ordered to Union Bridge in these events will be sent to Westminster.

General headquarters will be, in case of this movement, at Frizellburg; General Slocum as near Union Mills as the line will render best for him; General Reynolds at or near the road from Taneytown to l.

The chief of artillery will examine the line, and select positions for artillery.

The cavalry will be held on the right and left flanks after the movement is completed. Previous to its completion, it will, as now directed, cover the front and exterior lines, well out.

The commands must be prepared for a movement, and, in the event of the enemy attacking us on the ground indicated herein, to follow up any repulse.

The chief signal officer will examine the line thoroughly, and at once, upon the commencement of this movement, extend telegraphic communication from each of the following points to general headquarters near Frizellburg, viz, Manchester, Union Mills, Middleburg, and the Taneytown road.

All true Union people should be advised to harass and annoy the enemy in every way, to send in information, and taught how to do it; giving regiments by number of colors, number of guns, generals’ names, &c. All their supplies brought to us will be paid for, and not fall into the enemy’s hands.

Roads and ways to move to the right or left of the general line should be studied and thoroughly understood. All movements of troops should be concealed, and our dispositions kept from the enemy. Their knowledge of these dispositions would be fatal to our success, and the greatest care must be taken to prevent such an occurrence.

By command of Major-General Meade:

S. WILLIAMS,Assistant Adjutant-General.

Known commonly as the Pipe Creek Circular, this document was Meade’s plan to assume a formidable defensive position in Maryland that became known as the Pipe Creek Line, since it followed Big Pipe Creek. Shortly thereafter, Brig. Gen. Seth Williams, the Army of the Potomac’s adjutant general, sent out a correction to the Pipe Creek Circular:

MEMORANDA

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

July 1, 1863.

So much of the instructions contained in the circular of this date, just sent to you, as relates to the withdrawal of the corps at Emmitsburg should read as follows:

The corps at Emmitsburg should be withdrawn, via Mechanics-town, to Middleburg, or, if a more direct route can be found leaving Taneytown to the left, to withdraw direct to Middleburg.

Please correct the circular accordingly.

By command of Major-General Meade:

S. WILLIAMS, Assistant Adjutant-General

These two documents make it clear that George Meade had no intention of fighting in Pennsylvania on the eve of battle. That much is beyond dispute. Where the controversy arose is with whether Meade changed his mind on July 2, 1863 or whether he intended to withdraw the Army of the Potomac from its strong defensive position at Gettysburg.

The Pipe Creek Line ran just to the north of the town of Westminster, Maryland. Westminster, in particular, had great strategic significance to the Army of the Potomac, as the Western Maryland Railroad had its terminus there. The Western Maryland would serve as the primary line of supply for the army if it was going to operate anywhere in the vicinity (including at Gettysburg), and protecting it was critical.

Meade’s engineers did an outstanding job of selecting the Pipe Creek Line, something Meade himself recognized. As envisioned by the Union engineers, the Pipe Creek Line ran along Parr Ridge, a substantial ridge that ran on an east/west axis, and which extended from Manchester, Maryland on the east end to Middleburg, Maryland on the west. With the exception of some lower ground around Middleburg, the entire position was on very high, easily defensible ground that was probably impregnable unless the wily Robert E. Lee could manage to flank the federals out of their strong position.

Meade did not make a final decision to stay and fight at Gettysburg until he held a counsel of war at his headquarters on the night of July 2; he was willing to still consider falling back to Pipe Creek if seriously threatened. Two writings by Meade support his contention. At 3:00 p.m. on July 2, just before Lt. Gen. James Longstreet opened his sledgehammer attack against the Union left at Gettysburg, Meade sent a dispatch to General-in-Chief, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, “If I find it hazardous to do so, or am satisfied the enemy is endeavoring to move to my rear, and interpose between me and Washington, I shall fall back to my supplies at Westminster,” suggesting that if there was a threat to his flank or rear, he intended to abandon his position at Gettysburg. Meade elaborated on his thought process in an 1870 letter. “Longstreet’s advice to Lee was sound military sense; it was the step I feared Lee would take, and to meet which, and be prepared for which was the object of my instructions,” he explained. “But suppose Ewell with 20,000 men had occupied Culp’s Hill and our brave soldiers had been compelled to evacuate Cemetery Ridge and withdraw . . . would the Pipe Clay Creek (the real military feature is Parr Ridge which extends through Westminster) order have been so very much out of place?”

Ultimately, Meade decided to stand and fight at Gettysburg. Again, that much is beyond dispute and is not controversial. The controversy is whether Meade actually intended to retreat and to withdraw the army to the Pipe Creek Line. We will address that controversy in the next blog post.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Comments

Comments are closed.