My fellow blogger Harry Smeltzer is fond of pulling threads and examining family ties. And no, I am not referring to the popular Michael J. Fox television show from the 1980’s. Instead, the idea is to choose a personality and see what family ties can be found by pulling on a few threads. Harry has done some excellent thread pulling with respect to Judson Kilpatrick.

My fellow blogger Harry Smeltzer is fond of pulling threads and examining family ties. And no, I am not referring to the popular Michael J. Fox television show from the 1980’s. Instead, the idea is to choose a personality and see what family ties can be found by pulling on a few threads. Harry has done some excellent thread pulling with respect to Judson Kilpatrick.

I got the new issue of Patriots of the American Revolution yesterday (in the interest of full disclosure: Patriots is a sponsor of this blog). The cover story is about General Hugh Mercer, who was mortally wounded in action at the Battle of Princeton. That was a very fortuitous thing, as it ties into my current project and, if I pull the threads, it leads directly to one of my very favorite military figures of all time, General George S. Patton, Jr. This will be one of a couple threads that I intend to pull about General Patton.

Hugh Mercer was born in Scotland on January 17, 1726. At the young age of 15, he graduated from college and became a physician. He was present at the 1746 Battle of Culloden, serving as a physician in Bonny Prince Charlie’s army, which suffered a crushing defeat. Forced to flee Scotland as a result, the young doctor immigrated to America, settling near Mercersburg, PA, where he practiced medicine for eight years (the town was not known as Mercersburg then, but the name was changed to honor General Mercer).

Hugh Mercer was born in Scotland on January 17, 1726. At the young age of 15, he graduated from college and became a physician. He was present at the 1746 Battle of Culloden, serving as a physician in Bonny Prince Charlie’s army, which suffered a crushing defeat. Forced to flee Scotland as a result, the young doctor immigrated to America, settling near Mercersburg, PA, where he practiced medicine for eight years (the town was not known as Mercersburg then, but the name was changed to honor General Mercer).

In 1755, and appalled by the butchering of Brig. Gen. Edward Braddock’s army in its unsuccessful attempt to capture Fort Duquesne, Mercer went to aid the wounded. By 1756, he had been commissioned a captain in a Pennsylvania regiment, and was promoted to colonel. Along the way, he forged a warm, lifelong friendship with another colonial colonel, George Washington of Virginia. Both then served under General John Forbes during the second attempt to capture Fort Duquesne. At the end of the successful campaign, Forbes’ ill health forced him to return to Philadelphia, leaving Mercer in command of the fort and the settlement that grew up around it, Pittsburgh.

In 1760, Mercer settled in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he established a medical practice and apothecary. He purchased Ferry Farm–George Washington’s childhood home–from Washington. Mercer was involved in patriot affairs, and was appointed colonel of the 3rd Virginia Regiment in January 1776. Six months later, he was appointed a brigadier general in the Continental Army. Mercer originated the plan that led to the successful Battle of Trenton, and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. He died on January 12, with these as his last words: “What is to be, is to be! Goodbye, dear native land! Farewell, adopted country! I have done my best for you! Into thy care, O America, I commit my fatherless family! May God prosper our righteous cause! Amen!” He rests in Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. A photo that I took of General Mercer’s grave on a prior visit to Laurel Hill Cemetery can be found here.

One of Mercer’s grandsons was Col. George Smith Patton, who was the victorious commander in the August 26-27, 1863 Battle of White Sulphur Springs, which is the subject of the book manuscript that I will finish up in the next week or so.

One of Mercer’s grandsons was Col. George Smith Patton, who was the victorious commander in the August 26-27, 1863 Battle of White Sulphur Springs, which is the subject of the book manuscript that I will finish up in the next week or so.

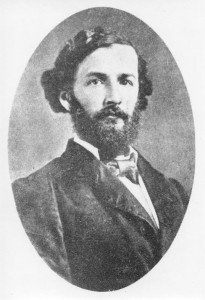

Patton was born in Federicksburg, Virginia in 1833. He was tall and slender, like his mother, and had dark, curly hair and dark eyes. Colonel Patton graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1852, and then helped to found a private school in Richmond, where he served as assistant principal and taught mathematics and English, all the while studying law in the hope of joining the Virginia bar.

He married in 1856 and relocated his new family to Charleston, the eventual capital of West Virginia, where he started a law practice with a partner. He soon founded a volunteer militia company known as the Kanawha Riflemen.

When war came in the spring of 1861, the Kanawha Riflemen became Co. H of the 22nd Virginia Infantry. Patton was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the regiment and was ordered to report to Brig. Gen. Henry Wise’s Army of the Kanawha. Patton was badly wounded in action during the July 1861 Battle of Scary Creek, where he was left behind as too badly hurt to be moved.

After being exchanged, he eventually returned to duty and received a second serious combat wound near Giles Court House, in southwestern Virginia in May 1862. He was shot in the belly, and in those days, most gut shots were fatal. Patton himself believed that the wound was mortal, but a gold coin in his pocket saved his life by preventing the bullet from fully entering his abdominal cavity. However, he developed blood poisoning and had to go home to recuperate from his second serious combat wound. He also learned that his exchange had never been formally completed, meaning that he could have been shot if captured again for violating his parole. Nevertheless, when Patton returned to duty, he was commissioned colonel of the 22nd Virginia. Interestingly, three of his brothers also served as colonels of Confederate regiments.

A friend described Patton:

His various and accurate learning revealed talents of a high order and of unusual versatility. To concentrate his thoughts upon a subject before him was natural and easy—not a laborious and painful exercise. Rapidly scouring the page, his eye would as quickly transfer to his mind whatever value it contained. Preferring the profession of law to any other business, and the sanctities of home and family to all other pleasures, he had, nevertheless, peculiar aptitude for a soldier’s duty and a soldier’s life. He enforced discipline without exciting dislike, and commanded his men without diminishing their self-respect. No private was ever denied the pleasure of conversation with his commander, and a courteous reception awaited all who chose to visit his quarters. When duty compelled him to deny a request, it was done with such evident reluctance, or with such kindliness of manner, that refusal gave less pain than is often suffered when a favor is granted with roughness or unwillingly.

Due to the frequent ill health of his brigade commander, Brig. Gen. John Echols, Patton frequently commanded the brigade that included his 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment. Patton led the brigade so ably that it was often called Patton’s Brigade, and not Echols’ Brigade. He commanded Echols’ brigade at White Sulphur Springs and defeated William Woods Averell’s Fourth Separate Brigade in a grinding, two-day battle. Patton was recommended for promotion to brigadier general as a result of his outstanding performance at White Sulphur Springs, but the Confederate Senate did not confirm the promotion in a timely fashion. The Senate’s failure to confirm the promotion in a timely fashion meant that notice of his promotion never reached Patton while he was still alive. Patton was mortally wounded on September 19, 1864 during the Third Battle of Winchester, and died a few days later. He was buried with his brother, Col. Waller Tazewell Patton, who was mortally wounded during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, in Winchester’s Stonewall Cemetery.

Four years after George Patton’s death, his 11-year-old son, originally named George William Patton, asked his mother for permission to change his name to George Smith Patton, to honor the dead war hero. His mother granted permission, and the boy changed his name. He became a renowned and prominent attorney in California, and his son, named George Smith Patton, Jr., went on to become America’s most successful battlefield commander during World War II.

George Smith Patton was the grandfather of the great World War II general, George S. Patton, Jr. Thus, there is a direct link between Hugh Mercer, Revolutionary War hero, and the great World War II hero who was his great-great grandson. I will pull together a few other threads regarding General Patton soon.

Scridb filterComments

Comments are closed.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like

Thanks for the interesting and informative post on one of my favorite historical figures.

Robert Krick also wrote an excellent essay on the fighting Pattons in the book ‘The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864’ published by the University of North Carolina Press.

Chris

Question: why, when the son changed his name, did he not become “junior,” making the WW II GSP “III”?

You be heading there, but allow me to note that Mercer’s grandson John Mercer Patton, a Virginia Congressman and in 1841 briefly Virginia’s acting governor, is another notable descendant. One of John’s eight children was the ill-fated Col. George Smith Patton (which means that George is Hugh Mercer’s great-grandson — small correction). John Mercer Patton’s proudest achievement was being the major re-organizer of Virginia’s legal code in 1850. That, I presume, is why the column rising from his grave at Richmond’s Shockoe Hill Cemetery is topped with a stack of books.

I don’t know, Bob. That’s a good question, but I can’t answer it.

Interesting stuff, Jeffry. Thanks for sharing that!

Eric

And then there’s Johnny Mercer the song writer . . . a several more times great grandson

And then there’s Johnny Mercer, the songrwiter, a several more great’s grandson

Bob,

I believe the Jr. question is answered in the excellent book about Patton by Carlo D’Este. Don’t have it at hand right now though.

Patton’s father was born George William Patton then changed his name in 1868 to honor his father (Patton’s Grandfather).

Chris

Patton was wounded at 3rd Winchester and later died from its effect. His brigade broke under the assault of Custer’s and Devin’s cavalry, who caught him during a withdrawal.

The family story is that Patton was wounded in town while trying to rally his men. He was hit in the leg, unhorsed and captured. The story is that he refused the have the leg amputated and enforced his decision with a cocked pistol. Unfortunately this led to his demise as the wound became infected, whereas amputation might have saved his life.

Enjoyed your article very much. I especially enjoyed reading about General Echols. I lived off Echols Street in Alexandria, VA, many years ago. At the time I looked up General Echols and found he was a very big guy. Strangely enough I ran into a fellow member of the Army JAG Corps whose name tag was “Echols”. He was a big guy 6’6″. Turns out he was the General’s direct descdant! Looked just like the picture of gg-grandpa! Small world.

I have recently discovered your blog and it is very interesting and fun to read. I am sharing it with my second son who is currently active military.