Category:

Battlefield preservation

Clark B. “Bud” Hall, who is the individual most responsible for the saving of the Brandy Station battlefield, has a good column on the preservation of the battlefield that appears in the current issue of Civil War News, which I commend to anyone interested in the history of the preservation effort there.

Brandy Station

By Clark B. Hall

(May 2013 Civil War News – Preservation Column)Col. John S. Mosby certainly knew more than most about fighting on horseback and his conclusion that the Battle of Brandy Station, June 9, 1863, was “the fiercest mounted combat of the war — in fact, of any war,” must today receive weighty consideration.

A staff officer to Jeb Stuart concurred when adding, “Brandy Station was the most terrible cavalry fight of the war” and the “greatest ever fought on the American continent.”

It is indisputable that Brandy Station was the largest cavalry battle of the war but we also concur with another distinction posited by a battle participant. Summoned in 1888 to offer dedicatory comments for the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry Monument at Gettysburg, Col. Frederick Newhall asserted the following:

“From my point of view, the field at Gettysburg is far wider than that which is enclosed in the beautiful landscape about us …. The larger field of Gettysburg … is the great territory lying between the battleground and the fords of the Rappahannock in Virginia.

“And while Gettysburg is generally thought of as a struggle which began on the 1st and ended on the 3rd day of July, 1863, the fact will some day be fully recognized that it had its beginning many miles from here …. It was at Beverly Ford then that Gettysburg was inaugurated.”

So with Brandy Station acknowledged as the grandest cavalry battle of the war and equally renowned as the inaugural action of the war’s threshold campaign — both matters of no small distinction — we who serve Brandy Station do “fully recognize” that the Sesquicentennial recognition of such a momentous battle must be commensurate with the import of this “sudden clash in Culpeper, precluding the thunder at Cemetery Hill.”

It is further emphasized that 20,000 soldiers fought at Brandy and many of them never departed as they are buried there yet today.

There is a myth suggesting that soldiers killed at Brandy were all disinterred after the war and given a “proper burial” elsewhere. This is a cynical myth, and one advanced by those who aimed to treat the battlefield as a utilitarian commodity.

So, our foremost duty 150 years later mandates we not only memorialize the courage and sacrifice of horse soldiers who fought and died at Brandy Station, but that we also tenderly treat the battlefield as a combat cemetery — because this is exactly what it is.

As one who has been on duty at Brandy Station since a California developer and a New York Formula One racetrack promoter deigned to destroy America’s greatest cavalry battlefield in the late 80s, I can tell you from long experience that the preservation path which led us to this point of a largely-preserved battlefield has been both tortuous and intense. Briefly, I’ll describe this heavy backdrop.

After the war, the Brandy Station Battlefield went “back to crop,” an appropriate economic configuration considering the large, open and well-watered fields have been farmed since the Colonial Era.

Indeed, when I first tried to comprehend this huge battlefield in the mid-‘80s, much of the land was comprised of several large farms, most in excess of 500 acres.

I became friends with area farmers and they granted me permission to stroll their farms with my maps in hand. It was a farm owner, in fact — my lamented friend, Bob Button — who first informed me in late 1987, “Bud, someone from California just bought my farm.” (This farm, the wartime “Cunningham Farm,” comprised John Buford’s attack platform on the morning of June 9.)

I can still recall today the uneasy feeling that washed over me when I considered Bob’s words, “someone from California….” Well when Fred Gordon shortly thereafter sold his adjacent farm (Rooney Lee’s defensive position, the “Green Farm”), I determined to find out exactly who was buying these farms.

It didn’t take long to reveal that the new owner of these two farms and, soon, several more nearby — amassing almost 6000 acres — was a commercial developer from Irvine, Calif.

We often hear the axiom that timing is everything, and for once, timing favored the good guys. Brian Pohanka, Ed Wenzel and I had previously formed the “Chantilly Battlefield Association” and we had just fought a mostly losing battle when trying to protect that sanguine battlefield from commercial development.

As a direct result of this failed preservation ordeal, a new nationwide battlefield preservation organization had formed and was solidly in place just before Brandy Station was slated for wholesale destruction.

Dr. Gary Gallagher, President of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites Inc. (APCWS), asked me to give the board a briefing on this terrible threat to Brandy Station.

Following that long update, Dr. Gallagher and the board authorized me (ordered me, actually) to meet with the developer and determine his plans.

The developer’s expressed intentions: “To farm the property.” Did we believe him? Not hardly. In fact, we girded for the battle to come.

And when considering that singular APCWS decision to become involved in Brandy Station’s preservation over 25 years ago has resulted in so much that has proven eternally good, it is appropriate that you consider the names of these few, good men who made that fateful decision on May 15, 1988:

Gary Gallagher, Bob Krick, Jack Ackerly, Merle Sumner, Don Pfanz, Alan Nolan, Will Greene, Dennis Frye, Brian Pohanka, Chris Calkins and Ed Wenzel… Brandy Station heroes, all of them, and but for their courageous decision to “get involved,” Brandy Station would now be an industrial office park, or a Formula One racetrack.

Point being APCWS showed preservation leadership when it most counted.

Many contentious years of lawsuits ensued against the developers by the APCWS-created and funded Brandy Station Foundation and finally resulted in developer bankruptcies. And after sweeping away our collective tears at the “tragic” demise of these star-struck developers, APCWS purchased hundreds of battlefield acres for millions of dollars in 1996.

Today, the Civil War Trust — the extraordinarily effective successor organization to APCWS — controls almost 2,000 acres at Brandy Station. But, although much has been accomplished, it is a reality that yet remains to be accomplished.

The hallowed ground CWT presently owns and controls at Brandy Station is vitally significant ground, to be sure, but the most significant military acreage on the entire battlefield has remained in private hands all these years, to wit: Fleetwood Hill.

Fleetwood Hill is without question the most fought over, camped upon, and marched over real estate in the entire United States.

From March 1862 to May 1864, Fleetwood Hill — especially the southern terminus — witnessed hotly-contested actions and heavy troop occupation as both Blue and Gray armies jockeyed for control of the strategically significant “Rappahannock River Line,” situated just three miles north of Fleetwood.

As one Confederate officer put it, “Fleetwood Heights … commands the country and … there was no movement of troops across Culpeper that artillery did not blaze from its summits, and charging squadrons … did not contend for supremacy.”

Recently, the Civil War Trust has undertaken steps to secure the 61 precious acres that comprise the entirety of the southern terminus of Fleetwood — Gen. Jeb Stuart’s Headquarters during the battle.

The price tag is steep and there is no guarantee of success, but for the first time in modern history Fleetwood Hill is for sale and CWT is doing everything in its power to close the deal.

We can help, each of us, to make this happen and I urge you to do your part, if you can. Here is how:

Please visit the Trust’s website, www.CivilWar.org, and click on the link, “Civil War Trust Announces Preservation Opportunity on the Brandy Station Battlefield.”

After reviewing the details, and if you are so inclined (and I sincerely hope you are), please click the “Donate” link and join with many others who believe saving Fleetwood Hill is a national preservation priority of the highest rank.

On June 8, by the way, the esteemed Loudoun County (Va.) Civil War Round Table is hosting an all-day tour at Brandy Station to commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the battle. For tour details, please see their website, lccwrt.wordpress.com. And if you attend, we promise you a cavalry battlefield outing that you will not soon forget.

To donate to our efforts to save Fleetwood Hill, please click here.

To register for the June 8, 2013 tour of the battlefield, please click here. I look forward to seeing some of you there.

Scridb filter Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

Lt. Louis Henry Carpenter served in the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the Civil War, and fought at the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. I formerly profiled Carpenter in one of my forgotten cavalrymen profiles. Carpenter was one of those great natural soldiers with no formal military training who left his mark on the United States Army, including being awarded a Medal of Honor for his service commanding African-American horse soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian wars. Carpenter plays a big role in the July 3, 1863 Battle of Fairfield; he was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to report for duty on July 4 after the debacle at Fairfield.

We’ve long known that Carpenter–a very intelligent and literate man–left behind a large set of some of the best Civil War letters home to be found anywhere. They are located in his home town of Philadelphia at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The problem is that they are in bound volumes and HSP will not permit them to be photocopied. So, if a researcher wants to use them, they must be transcribed by hand, which is, to say the least, a great inconvenience. That’s why the letters have never been published as a set, even though they really deserve to be. He also published a number of good articles on cavalry service and a large family genealogy (Carpenter was directly descended from Samuel Carpenter, who was William Penn’s right-hand man, meaning he was a Philadelphia blue-blood). His brother, J. Edward Carpenter, served as a major in the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry–a Philadelphia regiment–and left behind one of the best contemporary accounts of what we now know as “Keenan’s Charge” on May 2, 1863 during the Battle of Chancellorsville. Both Carpenter brothers were good and prolific writers.

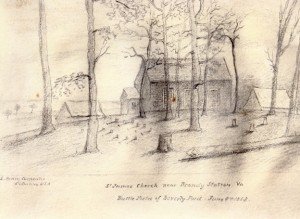

What we didn’t know is that the letters at HSP are only part of the collection of material he left behind. There are also diaries and a sketchbook of Carpenter’s observations during his time in the field during the Civil War. Bud Hall recently purchased this collection and found some amazing things therein. The most amazing find–and perhaps the most valuable of the images–is a sketch Carpenter drew in December 1863 of St. James Church–which sits in the middle of the Brandy Station battlefield, and was the site of the charges of the 6th Pennsylvania and 6th U.S. Cavalry during the morning phase of the the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. Carpenter drew the sketch just before the troopers of the 6th U.S. tore the church down to use the wood and pews for firewood and the bricks to build chimneys for their huts during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. This is the ONLY known contemporary image of the church, and it finally answers a question that those of us who study the Battle of Brandy Station have long wondered: What did St. James Church look like? Bud spent 25 years searching for a contemporary image of the little church and could never locate one. A 1989 archaeological survey of the church site told us what the footprint of the church looked like, and Bud speculated what it looked like, but nobody knew for sure. Thanks to Carpenter, we finally know the answer.

Below is a profile of St. James Church written by Bud Hall that gives the history of this otherwise obscure little church in the woods:

The Little Church that Would Not Die–St. James Episcopal: Rebirth of a Country Church

Richard Hoope Cunningham and his wife Virginia (Heth) arrived in Culpeper in 1833 and built a magnificent home, “Elkwood,” fronting the Rappahannock. Devout Christians, the Cunninghams routinely forded the river and attended services in Fauquier.

Weary of traversing a waterway that often proved dangerously swollen, the Cunninghams selected two acres about two miles back from the river as a suitable church site. Along with their neighbors, the Cunninghams then endowed the construction of a “first class country church.”

The two-story church—made of red brick fired on-site by slave labor—stood 40 by 40 feet, was “carpeted and nicely furnished, with cushioned pews.” Church officials were especially proud of its “big gallery all around for the colored people.” The total cost of construction materials was about $2000.

The beloved Rev. John Cole served as the first Rector of the new church in 1840, later consecrated in 1842 as St. James Episcopal Church. By 1860, the congregation boasted 28 communicants, with 40-50 black and white souls attending weekly services. A cemetery was laid out and all races were interred therein, with the same lovely periwinkle covering all beneath.

The little church proved so prosperous a parsonage loomed, and St James’s members donated $3000 to that end in 1861. But as events transpired, this munificent outlay soon reverted back as member families needed those funds for the next four years. War had come to Culpeper, and almost all of the county’s cherished churches were tallied as casualties during the ruinous conflict. And St. James was the first Culpeper house of worship to experience defilement, and then finally, total destruction.

Located near the wartime intersection of three roadways—Beverly’s Ford Road; Winchester Turnpike and Green’s Mill Road—St. James’s strategic placement near the river guaranteed the modest structure would suffer an inevitable concussive impact centered as it was between contending armies.

And by the thousands, Blue and Gray combatants tramped and fought about St. James. In 1862, pews were removed to enfold Rebel dead incurred in a fierce artillery duel. On June 9, 1863, fighting raged in front of St. James as Jeb Stuart’s legions beat back Federal charges during the Battle of Brandy Station. Several Rebel soldiers killed nearby sleep their final rest today in St. James’s burial ground.

Two Union soldiers in late 1863 left insightful glimpses of St. James: The first, an Illinois trooper, gazed upon the church and wrote his Chicago parents, “I admire the taste of Virginians in regard to building churches. They are not imposing structures and are always located in the woods.” A Pennsylvania officer described St. James as a “modest sanctuary…suggesting a time back when the woods were the first churches.”

Ironically, this latter soldier participated in taking St. James apart brick by brick in December 1863 to be used as chimney material during the winter encampment of the Army of the Potomac. Soon there was nothing left. Even the church bible was stolen. Robbed of their precious church, St. James members “worshipped God, like the primitive Christians, in private homes.”

But all wars finally do end, and in 1865, a new church was sought to replace St. James. We don’t know why the former site of St. James was not utilized; perhaps the reasoning suggested nothing more than the fact Brandy Station offered convenience for a post-war congregation. And then again maybe the bitterness over the loss of their lamented country church precluded a return to the “crime scene.”

“St James Church has risen from the ashes in the embodiment of Christ Episcopal Church at Brandy Station,” an exultant Rev. John Cole proclaimed in 1868.

In 1869, the new church was dedicated and consecrated “to supply the place of the building…entirely destroyed during the recent war.” Still offended at the wanton destruction of St James, Christ Church petitioned the Federal government for compensatory redress, and in 1914 the U.S. Court of Claims allowed the sum of $1,575 expended “as an equitable claim …that the United States received the benefit of the use of the material claimed for.”

Having fulfilled its duty by satisfying the honor of its ancestor church, the esteemed Christ Church congregation now also has St. James’s bible back in the fold—graciously returned by a former enemy. Christ Church continues today to hold in trust for the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia the St. James Church parcel, and the Brandy Station Foundation deferentially maintains, under lease, this beautiful, sacred church ground and its lonely cemetery.

Enter St. James today, if you will, and quietly and reverently experience the holy memory of a little church in the woods that refused to die.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

And without further adieu, here is Louis Henry Carpenter’s previously unknown sketch of St. James Church. It is important to note that Bud Hall owns this image and all rights associated with it. Bud gave me the privilege of being the first to see–and publish–this image, which will appear in Bud’s forthcoming comprehensive study of the Battle of Brandy Station when it’s completed (which will occur once the campaign to raise the funds to save Fleetwood Hill ends–please donate here). However, it cannot be duplicated or otherwise used without Bud’s express written permission. Please contact me if you want permission to use it for any reason, and I will put you in touch with him. Please click the image to see a full-sized version of it.

The image is very accurate: the graves are correctly shown, as is a defensive trench just beneath the gravestones, and if you visit the site today, you can still find the same small grouping of graves nestled among a grove of trees grown up since the war.

The self-portrait of Carpenter at the top of this post also comes from the sketchbook acquired by Bud. The same rules apply to it. I had looked for an image of him for years, but could only find one from late in his career, so I am very pleased to finally see a wartime image of him. You can see a larger image of it by clicking on it, too.

Bud has very generously agreed to permit me to use any of these images, and any of the other material that he now owns, in a future volume on Carpenter. I haven’t quite decided whether to edit the letters or to write a full-length biography of this fascinating soldier, but I will do something with them that makes good use of Bud’s collection of outstanding primary source material from Carpenter himself.

I’m tickled to be able to offer you the first look at these materials. Thanks to Bud Hall for permitting me to do so.

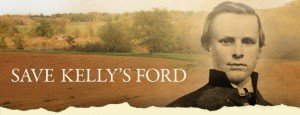

Scridb filterFor those interested in the upcoming Sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford (fought on March 17, 1863), my friend and fellow BSF board member in exile Craig Swain is leading a commemoration of the battle next Sunday (St. Patrick’s Day), from 2:00-3:15. The commemoration will occur on the battlefield proper, at the time when the battle was taking place. The event is to both commemorate the battle, but also to dedicate a new interpretive spot on some of the ground preserved last year by the Civil War Trust.

Craig has further details on his blog. If you’re in the area, please check out this event!

Scridb filter The current issue of Civil War News has an article about the Civil War Trust’s efforts to raise the money to purchase Fleetwood Hill. Disregard the astonishingly pathetic, lame excuse by Useless Joe McKinney as to why the BSF did nothing about the Lake Troilo episode (nice try, Useless Joe, but it does nothing to lend any credibility to your claims to support preservation), and you’ve got a nice overview of the situation here:

The current issue of Civil War News has an article about the Civil War Trust’s efforts to raise the money to purchase Fleetwood Hill. Disregard the astonishingly pathetic, lame excuse by Useless Joe McKinney as to why the BSF did nothing about the Lake Troilo episode (nice try, Useless Joe, but it does nothing to lend any credibility to your claims to support preservation), and you’ve got a nice overview of the situation here:

CW Trust Contracts For 61 Brandy Station Acres; Must Raise $3.6 Million

By Scott C. Boyd

(February/March 2013 Civil War News)BRANDY STATION, Va. – The Civil War Trust announced Dec. 20 it has a contract to buy 61 acres on historic Fleetwood Hill at Brandy Station for $3.6 million. The Trust has until June 7 to raise the money and close the sale, two days before the battle’s sesquicentennial.

The land at the crest of the southern end of Fleetwood Hill is the “crown jewel” of the Brandy Station battlefield, according to battle historian and Brandy Station Foundation co-founder Clark B. “Bud” Hall. It includes the site of Confederate commanding general J.E.B. Stuart’s headquarters for the battle.

“Protection of this property at the epicenter of the Brandy Station battlefield has been a goal of the preservation community for more than three decades,” said Trust President James Lighthizer in announcing the contract.

The Trust owns 878 acres of the Brandy Station Battlefield that are open to the public with signage, walking trails and a driving tour.

Unlike most Trust land purchases, this recent one became public before the Trust board had officially voted to approve the deal.

“Typically we wait until the board approves a transaction,” said Trust Director of Policy and Communications Jim Campi. “However, the news of it being under contract was leaked to the Culpeper paper, so it came out sooner than anticipated.”

Campi said the Trust’s board will make a formal decision on the purchase at its March meeting.

The Trust hopes to raise the money through $1.6 million in government grants and $2 million from private donors, according to Campi. “We need everybody involved with this deal. It’s a big number in a tight economy,” he said.

The government grants will likely be a combination of federal money from the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program and funds from Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources, Campi said.

“The key is to raise $2 million in private sector money,” he said. “Bud Hall has taken the lead in helping us identify big donors to help us get to that $2 million goal.”

Campi said, “We are concerned about the big amount of money that needs to be raised in a short amount of time.”

While being confident that Trust members “are going to step up like they always have,” he said the Trust hopes a broader group will get involved as well.

“Any help we can get from the Civil War community would be appreciated,” Campi said.

“It’s a steep uphill climb to get that $3.6 million by the sesquicentennial anniversary. We’re committed to doing our best to get there.”

The Trust plans a Fleetwood Hill Appeal mass mailing in February or March to initiate the public fundraising campaign.

Background

The Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, was the largest cavalry battle in the Civil War with 18,456 cavalry from both sides and an additional 3,000 Union infantry engaged. It was the opening phase of the Gettysburg Campaign, taking place just three weeks before the battle. In late July Confederates retreating from Gettysburg camped at Brandy Station.

“Fleetwood Hill is without question the most fought over, camped upon and marched over real estate in the entire United States,” Hall wrote in a monograph describing the Battle of Brandy Station and Fleetwood Hill’s role in the Union Army winter encampment of 1863-1864. The army left on May 4 for the Overland Campaign.

Hall said the hill was of strategic importance because artillery placed there controlled five important road junctions that converged in Brandy Station village three quarters of a mile away. And the Orange and Alexandria Railroad passed the southern base of the hill.

“Although it is most closely associated with the climactic fighting of June 9, 1863, there were, in fact, 21 separate military actions on Fleetwood Hill during the Civil War — far more than any other battle venue in this country,” Hall wrote.

Joseph Anthony “Tony” Troilo Jr., who has contracted to sell the 61 acres, said the land has been in his family for 40-45 years.

Preservationists last considered buying the property in 2002, but were unsuccessful. Hall, who participated in those negotiations with Lighthizer, said Troilo asked $4.9 million, which “far exceeded our ability to acquire it, at the time.”

In the spring of 2011, Troilo dammed the perennial stream, Flat Run, without a federal permit, to create a pond on his property (see July 2011, January 2012 CWN).

Hall notified the Army Corps of Engineers about this violation of the Clean Water Act and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. Subsequently Troilo agreed to remove the dam and restore the land and stream to their previous condition.

The Brandy Station Foundation’s (BSF) lack of action created a backlash against the BSF by some in the preservation community.

BSF President Joseph W. McKinney recently said the foundation did not want an adversarial relationship with Troilo for strategic reasons.

“We wanted to maintain good relations. The main thing I wanted to ensure was that if they came to a decision to sell, that they would be amenable to selling to preservationists,” he said.

The current deal began when Troilo and his wife put the property up for sale in late November 2011.

The controversy earlier that year over the pond was a factor in Troilo’s decision to sell. Troilo said, “No doubt, I’m sure it had some significance.”

McKinney said he was the first person Troilo told about selling and he notified the Civil War Trust.

The 2012 negotiation of the sales contract was conducted by Trust officials and Troilo.

A new appraisal, upon which the current deal was based, set the value of the 61 acres, including two houses, a pool, tennis court and other outbuildings, at $3.55 million. The Trust offered Troilo $3.6 million, which he accepted.

“It really makes sense for the Civil War Trust and Brandy Station Foundation to own that property because of the significance of the battle,” he said.

“That would put all the pieces of the puzzle together, and they would actually own what they tried to fight for 150 years ago.”

Said Hall about the pending purchase, “I could not possibly be more excited.”

Donations to the Fleetwood Hill Appeal and information about the battlefield can be found at the Trust’s website:

www.civilwar.org/battlefields/brandystation/brandy-station-2013/

The photo shows BSF founder (but banned from membership by Useless Joe and the Board of Appeasers) Bud Hall, standing on the opposite side of what would have been Lake Troilo (Flat Run runs through the low ground at the base of Fleetwood Hill), pointing up at Tony Troilo’s McMansion, which is where Jeb Stuart’s headquarters was on June 9, 1863. Again, I give Tony Troilo a great deal of credit for doing the right thing and for agreeing to sell Fleetwood Hill to the Civil War Trust.

You can donate here.

Scridb filter Here’s some more good news on the “goodbye to ugly buildings on historical ground” front….

Here’s some more good news on the “goodbye to ugly buildings on historical ground” front….

The National Park Service is finally able to tear down the hideous Cyclorama building at Gettysburg, which was constructed in a place that never should have been chosen for it, the site of Ziegler’s Grove, in the Pickett’s Charge portion of the battlefield. The family of the architect of the hideous thing protested and dragged the National Park Service through years of needless litigation while the building continued to deteriorate. It’s finally time to be done with it.

From WITF today:

National Park Service to demolish Gettysburg Cyclorama building

Written by Craig Layne, Morning Edition Host/Reporter | Jan 10, 2013 12:21 PM(Gettysburg) — The National Park Service has chosen to demolish an architecturally significant building on the Gettysburg battlefield.

The Cyclorama building was designed by famed architect Richard Neutra and once housed a 360-degree painting of Pickett’s Charge.

The structure, which closed in 2005, has been the center of a struggle between the park service and modern architecture experts for more than a dozen years.

In an August interview with witf, NPS spokeswoman Katie Lawhon says tearing down the building would allow the agency to restore Cemetery Ridge to the way it would have looked during the three-day Civil War clash in July 1863.

“There were actually some monuments associated with soldiers from the Union Army that had to be moved when they built the building,” Lawhon says. “So, the first thing we would do is put the monuments back where the veterans had originally placed them.”

The park service reviewed the environmental impact of destroying the building before making its decision.

The agency says demolition could begin later this winter.

The Cyclorama painting is now on display at the Gettysburg National Military Park’s visitors’ center.

The National Park Service provided this background information on the building:

Gettysburg National Military Park – Cyclorama Building Background

In 1999, the National Park Service (NPS) approved a General Management Plan for Gettysburg National Military Park (NMP) that addressed demolition of the Cyclorama building as part of a long-term plan to rehabilitate the North Cemetery Ridge to its historic 1863 battle and 1864-1938 commemorative-era appearance.

The 1962 Cyclorama building, designed by noted architect Richard Neutra, was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The adverse effect of demolishing the building was addressed in a 1999 Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the NPS, the State Historic Preservation Officer and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. All mitigation in the MOA has been completed.

In 2006, the NPS was sued by the Recent Past Preservation Network and two individuals challenging the government’s compliance with both the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in making the decision to demolish the Cyclorama building. The U.S. District Court found that the NPS had complied with NHPA but not NEPA and directed the NPS to undertake a “site-specific environmental analysis on the demolition of the Cyclorama Center” and to consider “non-demolition alternatives” to its demolition before “any implementing action is taken on the Center.”

Accordingly, the NPS initiated an environmental assessment (EA).

The Environmental Assessment planning process – The park prepared the EA with assistance from the regional office and with input from the Northeast Regional Solicitor’s Office and the WASO Environmental Quality Division. The EA evaluated three alternatives: the NPS preferred alternative to demolish the building; another action alternative to allow a third-party to relocate the building outside park boundaries; and the no action alternative to mothball the building in place.

The EA was released for a 30-day public review and comment period that ended on September 21, 2012. Over 1,600 pieces of correspondence were received on the EA. The majority of commenters supported demolition of the building in order to rehabilitate the battle and commemorative landscapes. All substantive comments have been addressed in consultation with the regional office and the Northeast Regional Solicitor’s Office.

No changes to the NPS preferred alternative were warranted as a result of public comment.

Next Steps – Gettysburg Foundation has funds for the demolition of the building and for most of the rehabilitation of Ziegler’s Grove. The first steps in the project will be several weeks of asbestos remediation.

Once the building is demolished, the battle and commemorative-era landscapes will be rehabilitated according to the treatment recommendations contained in the 2004 cultural landscape report (CLR) for the North Cemetery Ridge area which include returning monuments to their historic locations, rebuilding commemorative pedestrian pathways and rebuilding historic fences.

Good riddance.

Next up, the horrendous McMansion on Fleetwood Hill……

Scridb filterAt the request of the Civil War Trust, I’ve written an article on the fighting for Fleetwood Hill that occurred on June 9, 1863. That article was posted today, and can be found here. I appreciate all of your help and support for our efforts to preserve THE most fought-over piece of ground on the North American continent.

You can donate here.

Scridb filterThe Brandy Station Foundation has finally issued a statement about the purchase contract for Fleetwood Hill:

MAJOR NEWS: CIVIL WAR TRUST TO BUY FLEETWOOD HILL

It is my pleasure to inform you that on December 19, the Civil War Trust and Mr. Joseph A. Troilo, Jr., reached agreement for the Trust to purchase Tony Troilo’s fifty-seven acre property at the southern end of Fleetwood Hill. A link to an article from the December 21 edition of the Culpeper Star-Exponent is:

http://www.dailyprogress.com/starexponent/news/local_news/article_8eb4f41c-4af0-11e2-a40e-001a4bcf6878.html.

This agreement is the culmination of more than twenty years preservation efforts in Culpeper County. However, major work remains: now the Trust must raise $3.6 million to pay for the property. We encourage you to support the Trust with your generous donations. Also, as you know, we are holding a ball at the Inn at Kelly’s Ford on the evening of March 16, 2013, to commemorate the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. We will donate one-half of the proceeds from the ball to the Trust. So, come to the ball, have a good time, and help pay for Fleetwood Hill.

Joseph McKinney

President, Brandy Station Foundation

Let’s not break our arms patting ourselves on the back, shall we?

Let’s remember that this is the same organization that stood by and did NOTHING when Troilo started digging his recreational lake, even though McKinney had advance knowledge that he was going to do so. Let’s remember that this is the same organization that issued a statement saying that it’s okay if a local landowner wants to dig up the battlefield for his or her own purposes. And most importantly, this is the same organization that sat on its hands and did NOTHING for months while this critical parcel of land was listed for sale with a realtor. It did NOTHING to arrange for the land to be appraised, and it did NOTHING to negotiate a deal with the Civil War Trust.

In short, the BSF has once again proved the truth of what I’ve been saying here all along: the current, incompetent leadership of the BSF is not interested in battlefield preservation, and its incompetent leadership has rendered the organization entirely irrelevant.

So, while I applaud Useless Joe McKinney and the Board of Appeasers for getting on the train once it had already left the station, the fact that it wasn’t the original passenger on the train is what I find terribly troubling. You should too.

Scridb filterToday’s issue of the Culpeper Star-Exponent contains an article about the purchase contract to save Fleetwood Hill that I discussed here yesterday. That article contains a statement by Tony Troilo that I find really perplexing: “[Troilo] credited Brandy Station Foundation President Joe McKinney as being instrumental to the sale. ‘He kept the CWPT in the mix,’ Troilo said.”

Those of us who make up the board in exile of the Brandy Station Foundation have been in constant communication with Bud Hall about this. And Bud has been in constant communication with the Civil War Trust about this, and NOBODY has said a word about either the BSF or Useless Joe McKinney and his Board of Appeasers doing anything whatsoever about this. Indeed, this happened in spite of Useless Joe and his useless gang, not because of anything that they did. Indeed, when you do nothing, it’s hard to claim credit for doing something.

And so, I ask: What did you do, Useless Joe? What role did you play in preserving Fleetwood Hill? Pray tell. We would all like to know.

For the record, I would like nothing more than to be proved wrong, and if Useless Joe and the Board of Appeasers demonstrate to me that I am wrong, then I will gladly apologize. However, knowing what I know about this situation, I am not the least bit concerned about having to do so….

UPDATE, DECEMBER 24, 2012: As of today, there has not been even so much as a mention of the contract for the preservation of Fleetwood Hill on the Brandy Station Foundation’s website. This is, perhaps, the single most important land preservation deal yet signed, and certainly is the key acquisition of the Brandy Station battlefield. One would think that the BSF, allegedly the steward of the battlefield, would say something about such a critical transaction, but there is nary a word. This is yet more evidence of the fact that this organization is NOT interested in battlefield preservation. Either lead, follow, or step aside, Useless Joe and the Board of Appeasers.

Scridb filter From the gift that keeps on giving–the incompetent board of appeasers of the Brandy Station Foundation–we have this delightful little tidbit.

From the gift that keeps on giving–the incompetent board of appeasers of the Brandy Station Foundation–we have this delightful little tidbit.

You can’t make this stuff up, folks.

From Sunday’s edition of the Culpeper Star-Exponent:

By: Vincent Vala | Culpeper Star Exponent

Published: October 28, 2012

» 0 Comments | Post a Comment

The Halloween spirit visited Brandy Station this weekend as the Brandy Station Foundation offered up its annual “Spirits of the Graffiti House” event at the historic facility off U.S. 29 North Saturday evening.Between 6 and 9 p.m., the former Civil War hospital facility was open to the public for tours, treats and tales of the unnatural that have been reported at the Graffiti House over the years.

Visitors could mix history, All Hallows Eve and having fun, all it the good spirit of the harvest season.

“We kind of combine a lot of different things for the evening,” said Helen Geisler, a member of the BSF board of directors. “It’s just intended as a fun evening for the children – and for the adults.”

Geisler said this is the fifth year for the event.

“Last year, we had well over 100 people turn out,” she said. “So this year we’ve prepared for at least that many.”

Throughout Saturday evening, tour guides talked to visitors about the graffiti in the upstairs rooms of the house, while Transcend Paranormal Investigators gave talks in a downstairs room.

A video produced by the R.I.P. Files about their overnight stay in the house was played in the house’s entry room and BSF President Joe McKinney offered up stories of the supernatural to those seated around a campfire in the back yard as they roasted and snacked on marshmallows.

“We’ve had at least three or four different paranormal investigative groups here,” Geisler said. “I’ve had experiences in this house myself.”

The photo is of the BSF’s intrepid leader, Joe McKinney, telling ghost stories.

Now, I enjoy fun as much as the next guy, and I don’t mean to come across as a funkiller. However, how is this an appropriate activity for a supposedly serious preservation organization? This is the stuff that McKinney and the Board of Appeasers brag about in the BSF’s annual report, not the success of their efforts to preserve and maintain the battlefield. Apparently, the board’s major accomplishment this year has been toasting marshmallows with ghosts. It most assuredly was NOT preventing the destruction of core battlefield land by a landowner.

And then there’s this gem: Geisler said. “I’ve had experiences in this house myself.”

Do tell?

The BSF has made itself entirely irrelevant by engaging in such activities that have substantially less than nothing to do with the core mission of the organization, which is the preservation and stewardship of the battlefield. Please allow me to suggest that by engaging in such frivolous and undignified activities at a place where men suffered and died for a cause that they believed in dishonors them and their sacrifices. For shame.

Scridb filter While I’ve known about this for some time, it’s only just become a matter of public knowledge, and I’m excited about this preservation opportunity.

While I’ve known about this for some time, it’s only just become a matter of public knowledge, and I’m excited about this preservation opportunity.

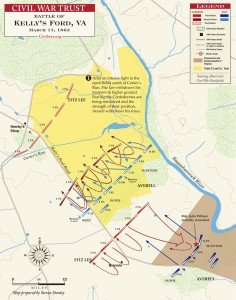

The Civil War Trust has announced a campaign to raise funds to pay for 964 acres of core battlefield land at Kelly’s Ford, near  Brandy Station. This represents almost 50% of the battlefield from the important March 17, 1863 cavalry battle between William Woods Averell and Fitz Lee’s troopers. The map shows where this particular parcel may be found. The land in yellow is the land in question. It was the scene of the most severe fighting of the battle. Click on the map to see a larger version of it.

Brandy Station. This represents almost 50% of the battlefield from the important March 17, 1863 cavalry battle between William Woods Averell and Fitz Lee’s troopers. The map shows where this particular parcel may be found. The land in yellow is the land in question. It was the scene of the most severe fighting of the battle. Click on the map to see a larger version of it.

With this large acquisition, combined with the significant portion of the battlefield owned by the Commonwealth of Virginia, nearly 75% of the entire battlefield will be safe. This is a rare and exciting preservation opportunity and one that I hope all of you will get behind.

It’s important to note that no river crossing saw more traffic during the Civil War than did Kelly’s Ford. Much of the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock River there on its way to Chancellorsville, there was an infantry fight there in November 1863, and two of the three divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps crossed there on its way to fight the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. This was probably the most famous and most important river crossing of the war, and the opportunity to preserve it is a rare one indeed.

It bears noting that this piece of the battlefield falls squarely within the bailiwick of the Brandy Station Foundation, which proudly touts that it’s going to hold an event to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford next March. However, the BSF did absolutely nothing whatsoever to help to arrange this deal or to help to raise awareness of it. Why? Because it’s got nothing to do with ghost hunting, relic hunting, or the Graffiti House (which are the things that the BSF bragged about in its 2011 annual report), and because President Joe McKinney and his board of appeasers have rendered the organization completely and entirely irrelevant. They’re just as irrelevant to this acquisition as they are to the ongoing efforts to acquire Fleetwood Hill–that is to say, wholly inconsequential. It is pathetic that the organization tasked with preserving the battlefield land in and around Brandy Station has been rendered so irrelevant that it probably had no idea that the Trust had made this deal before it was announced publicly on the CWT website today.

Because of that, all donations to preserve the Kelly’s Ford battlefield should be directed to the Civil War Trust and ONLY to the Civil War Trust. Send a message to McKinney and the Board of Appeasers: send them a copy of your donation check and let them know that if they were doing the job that they were sworn to do, that money would be coming to them and not to the Trust.

Thank you for your support for our efforts to save this important battlefield land.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like