Category:

Union Cavalry

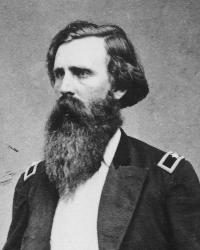

Time for another installment in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten Civil War Cavalrymen. Today, we feature Col. James H. Childs, colonel of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, who was killed in action at the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862.

James Harvey Childs was born on the 4th of July, 1834, at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father was Harvey Childs, a native of Massachusetts. His mother, Jane Bailey (Lowrie) Childs, was a sister of the Hon. Walter H. Lowrie, late Chief Justice of Pennsylvania. He was educated at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, where he graduated in the class of 1852. He stood six feet tall, was well-proportioned, and enjoyed good health. He was married on the 14th of July, 1857, to Mary H. Howe, eldest daughter of the Hon. Thomas M. Howe, of Pittsburgh.

James Harvey Childs was born on the 4th of July, 1834, at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father was Harvey Childs, a native of Massachusetts. His mother, Jane Bailey (Lowrie) Childs, was a sister of the Hon. Walter H. Lowrie, late Chief Justice of Pennsylvania. He was educated at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, where he graduated in the class of 1852. He stood six feet tall, was well-proportioned, and enjoyed good health. He was married on the 14th of July, 1857, to Mary H. Howe, eldest daughter of the Hon. Thomas M. Howe, of Pittsburgh.

After graduation, he settled in his home town of Pittsburgh, where he was a civil engineer and a wholesale dry good merchant and manufacturer of cotton goods. He became a prominent and well-respected businessman in the community.

Childs served as first lieutenant of a militia unit, the Pittsburgh City Guards, before the Civil War. When the call was made for troops in that struggle, he promptly tendered his services, and was commissioned first lieutenant of Company K, 12th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. After his short term of service expired, he became active in recruiting the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and was commissioned the new regiment’s first lieutenant colonel on October 18, 1861. On March 12, 1862, before his regiment took the field, he was promoted to colonel when the regiment’s original colonel was transferred to the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

In McClellan’s 1862 Peninsula Campaign, he served with his regiment, the scouting and skirmishing being unusually severe on account of the lack of troops in this arm of the service. His regiment opened the battle at Mechanicsville, during the first of the Seven Days’ engagements, and at Gaines’ Mill and Glendale, was actively employed, proving, in both these desperate encounters what a good regiment he led, as well as the steadfast purpose of its commander.

On evacuating the Peninsula, the regiment moved to Washington, arriving in time to join the Maryland campaign. At Antietam it was attached to Averell’s brigade, and on account of the sickness of General Averell, command of the brigade devolved upon Colonel Childs. The brigade was assigned to the left of the Union line, and after crossing the stone bridge, was posted in support of Clark’s battery, which was heavily engaged. The duty was difficult, and the enemy’s fire proved very destructive. Colonel Childs was upon every part of the field, encouraging his men, and intelligently directing the movements. He had just completed an inspection of the skirmish line and had returned to his headquarters, where he was cheerfully conversing with his staff, when he was struck by a cannonball on the left hip which threw him from his horse, and passed completely through his body.

For a time his mind was clear, and recognizing at once that his wound was mortal, his first concern was for his command. He dispatched Captain Hughes, one of his staff officers, to Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton, commander of the cavalry division assigned to the Army of the Potomac, to apprise him of his fall, and another to his regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Kerr, to request him to assume command of the brigade. He then sent a message to Dr. Marsh, that, “If he was not

attending to anyone whose life could be saved, to come to him, as he was in great pain.” Finally, he called to his side his Assistant Adjutant-General, Captain Henry King, a townsman, and personal friend, to whom he gave brief messages of affection to his wife and three little children. Of the oldest of the three, a boy bearing the name of his maternal grandfather, as if thinking in his dying moments only of his country for which he had perilled and lost his own life, he said: “Tell Howe to be a good boy, and a good man, and true to his country.” Twenty minutes later, he became delirious, and he died a few minutes later, joining the many other brave men who lost their lives on the bloody battlefield of Antietam. His remains were taken home to Pittsburgh, and were buried in Allegheny Cemetery.

After the war, when the Antietam battlefield was marked, Childs received a monument. Located on Maryland Route 34 near Antietam Creek, the simple stone monument says:

After the war, when the Antietam battlefield was marked, Childs received a monument. Located on Maryland Route 34 near Antietam Creek, the simple stone monument says:

At this spot Colonel James H. Childs of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry in temporary command of Averill’s Brigade fell mortally wounded on the morning of Sept. 17, 1862.

Here’s to forgotten cavalryman Col. James H. Childs, who lost his life at Antietam on the Civil War’s bloodiest day.

Scridb filterYesterday, I mentioned that Mort Kunstler had called me to discuss a painting he’s planning on doing of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Today, Don Troiani e-mailed me to let me know that he’s finally ready to begin working on a scene of the charge of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry at St. James Church during the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station that he’s been planning for the better part of ten years. He asked whether I’d be willing to help and answer questions for him on it, and I agreed. I’ve already given Don pretty much everything that I have on this episode, but I am nevertheless more than happy to help.

That makes two scenes of the Lancers by two prominent artists in two days. How cool is that?

Scridb filterI had a very interesting but surprising telephone call this morning. Renowned Civil War artist Mort Kunstler phoned me this morning, out of the clear blue sky. Mort has gotten interested in the Rush’s Lancers and figured out that I know something about them. He’s planning to do a painting of the Lancers, and got hold of me to see if I might be interested in helping. I’ve worked with Don Troiani, Don Stivers, and Dale Gallon in the past, and enjoyed each instance. So, I readily agreed to help Mort.

I quoted him my usual fee for helping: a copy of the print personally signed to me, and we had a deal.

I’m looking forward to working with him, and am especially looking forward to seeing my favorite regiment honored. I will keep everyone posted as to the progress of the project.

Scridb filterToday, I am going to profile a forgotten cavalryman named Bvt. Brig. Gen. Thomas Jefferson Jordan, who, like me, was an alumnus of Dickinson College, one of a number of notable cavalry officers who graduated from Dickinson.

Thomas Jefferson Jordan was born in December 3rd, 1821, to Benjamin Jordan and Mary Crouch on the family farm, Walnut Hill, in Paxtang, Dauphin County Pennsylvania. The family was of Scottish origin and came to this country in 1720, first settling in King and Queen County, Virginia. In 1742, his great-grandfather, James, left Virginia, and with his slaves came to Pennsylvania, where he bought a large tract of land on the Susquehanna River, near Wrightsville, York county. His grandfather, Thomas Jordan, was born in Cecil County, Maryland, and married Ann Steele, daughter of Capt. William Steele of Drumore, Lancaster County, PA and widow of Robert Dickson.

Benjamin Jordan was born near Milton, PA in 1779 shortly before the family fled due to Indian attacks. They later lived in Hopewell, York County, PA. During the war of the Revolution the grandfather was a paymaster with the rank of Major, and served as such during the entire war. The father married Molly, the only daughter of Edward Crouch, a Captain in the Revolutionary army, she being a granddaughter of General James Potter, of Pennsvalley, also a soldier of the Revolution. Jordan was paymster for General Potter in the Pennsylvania militia and fought with Potter in Chester County, PA.

Benjamin Jordan’s mother had three brothers that eventually became generals in the Revolution and War of 1812. His aunt, Rachel Steele, married Jacob Bailey, brother of Francis Bailey, and the Baileys and Steeles were involved in the printing trade for multiple generations with Francis Bailey printing newspapers, almanacs and becoming the official printer for Continental Congress, and a close friend of Benjamin Franklin and witness to Franklin’s will. Benjamin’s half brothers, William and Robert Dickson, were associated with the Lancaster Intelligencer and Benjamin had apprenticed there as a young man before going on to a career in politics . He was a friend of Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s first Secretary of War and was also an investor in the Bank of Middleton with Cameron.

Thomas Jefferson Jordan spent first fourteen years of his life in the local country school, along with the other farmers’ boys, remaining enrolled there until in the summer of 1839. In December, 1839, he enrolled in the Law Department at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, then under the leadership of its founder, Judge John Reed. He attended the College for the following two years and in February, 1843 was called to the Dauphin County bar in Harrisburg and opened a practice.

He practiced law and ran a lumber business in Harrisburg until the Civil War broke out. On April 17, 1861, the day after Fort Sumter fell, Jordan was commissioned as aide to Maj. Gen. William Hugh Keim, who was raising volunteers in Pennsylvania. He served Keim well. Jordan carried the first news of the riots in Baltimore to Bvt. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, and then commanded a brigade in the Shenandoah Valley. Jordan first saw action with Keim at Falling Waters in early July 1861, gaining valuable experience against the Virginia forces of Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston.

At the end of that campaign, Jordan was mustered out and received a new commission as a major. He was ordered to assist Col. Edward C. Williams in the recruiting and organization of a cavalry unit that became the Ninth Pennsylvania Cavalry in October 1861. This regiment was also known as the “Lochiel Cavalry” and as the 92nd Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers.

With Jordan commanding its Third Battalion, the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry was deployed to the Cumberland Valley and then was sent west to the column commanded by General Don Carlos Buell, then at Louisville, Kentucky, where it arrived in November, 1861. The regiment saw action in Kentucky and Tennessee in early 1862. At Tompkinsville, Kentucky, on July 9, 1862, a superior force of Confederate raiders under command of the dashing Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan surprised Jordan and three companies of the Third Battalion. Jordan organized a fighting retreat but elements of the rearguard and the major himself were captured by Morgan. He was sent to the Confederate POW camp at Madison, Georgia, and was later transferred to Richmond’s Libby Prison.

Once a prisoner of war, Jordan came under attack for alleged ill-treatment of civilians in Sparta, Tennessee the previous May and was moved from Libby Prison to Castle Thunder Prison to face charges. However, a subsequent investigation determined that his unit had only been in Sparta for a few hours and that the charges were based on Jordan’s demand to the women of the town quickly to prepare a meal for his men. He was exonerated and subsequently exchanged in December 1862.

Jordan returned to his regiment in January 1863. In the meantime the Colonel had resigned, and the Lieutenant Colonel was terminally ill. Jordan was, accordingly, appointed Colonel. At Shelbyville, Tennessee, on June 9, 1863, he led the charge on the left, a most gallant action, which scattered the enemy and put him to inglorious flight. At Thompson’s Station, when Colonel Coburn of an Indiana regiment had tamely surrendered, he brought off the surviving forces, saving the artillery and baggage, and fighting heroically against a force of 5000 cavalry, led by Nathan Bedford Forrest. At the moment when General Bragg’s army was retiring across the Cumberland mountains at Cowan, Tennessee, Colonel Jordan and his command charged and captured over five hundred prisoners.

In the Battle of Chickamauga, when ruin was impending on other parts of the field, he heroically defended the right of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, enabling that gallant soldier to stem the tide of disaster. His conduct so impressed Thomas that he asked President Lincoln to promote Jordan in recognition of his meritorious service at Chickamauga.

He fought and defeated Brig. Gen. George Dibbrell’s cavalry at Reedyville, though the latter was at the head of a force of 2500 men. He was active in the campaign against Longstreet in East Tennessee in the winter and spring of 1863-64, and fought in the battles of Mossy Creek, Dandridge and Fairgarden. In the battles of Lafayette, Dalton, Kenesaw, Big Shanty, Resaca, New Hope Church, Peach Tree Creek, and in front of Atlanta, Colonel Jordan was constantly engaged. When the enemy finally retreated, he followed close upon the trail and was sharply engaged with Wheeler’s troopers at Jonesborough and Lovejoy’s Station.

He was placed in command of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the cavalry in the March to the Sea, with which he met Wheeler at Lovejoy’s Station, and after a sharp engagement routed him and captured all his artillery, retaining the pieces which were of superior quality in his command until the end of the war. He again defeated Wheeler at Waynesburg, Georgia, where he led his brigade in a charge upon the enemy’s position, and ended the fight before the reserves, sent to his relief, could arrive. He first invested Fort McAllister near Savannah, driving the rebels within their works, and was only prevented from carrying them by assault by the arrival of General William B. Hazen, with his division of infantry, who superseded him in command.

On the march through the Carolinas Colonel Jordan crossed the Savannah River in advance of the infantry at Sister’s Ferry, and covered the Left Wing of Sherman’s army under command of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum. His position in the column on the march north was such that he was brought often to severe conflict. He led the charge at Blackville, dislodging the enemy from the town. He held the position at Lexington, protecting the flank of the infantry, while Columbia was being occupied. With Wheeler and Hampton he had a stubborn action at Lancaster, and crossing into North Carolina led the advance to Fayetteville, daily and hourly skirmishing heavily.

The Battle of Averasboro, fought on March 16, 1865, opened early in the day. Jordan’s brigade fought unaided until two in the afternoon, when the infantry of the Twentieth Corps came to his assistance. In this action, every twelfth man in his entire force was either killed or wounded. At Bentonville, he held the left flank, and participated in all the movements of the day. In the advance against Raleigh he again had the lead, and entered the city on the morning of April 12th, 1865. On passing through, he found that the rebel cavalry was ready for action on the Hillsborough road, and at once moved forward to the attack, driving them before him the entire day. At Morristown he was met by a flag of truce, with a letter for General Sherman from General Joseph E. Johnston, proposing to surrender, when fighting ceased. Jordan was brevetted to brigadier general of volunteers for his long and meritorious service in February 1865. The 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and Jordan with it, was mustered out on July 18, 1865.

He had married before the war and he corresponded extensively with his wife, Jane, during the war. After the war, he briefly returned to the legal profession in Harrisburg. A few years later, he went into the lumber business in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, but the business eventually failed. Perhaps due to his advanced age, he secured a position with the U. S. Post Office and then transferred to the U. S. Mint in Philadelphia. He died in Philadelphia on April 2, 1895 and was buried in Section 11, Lot 19 of the Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware. He was seventy-four years old.

Jordan was an able field commander who was well thought of by his superiors and respected by his men. Except during his time as a POW, he was constantly in the field with the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, in spite of bad health that often compelled him to accompany his command in an ambulance.

Here’s to forgotten cavalryman and Dickinson College alum, Bvt. Brig. Gen. Thomas Jefferson Jordan.

Scridb filterTime for another in my infrequent series of profiles of forgotten cavalrymen….

Andrew Jonathan Alexander was born to a wealthy and influential family in Woodford County, Kentucky on November 21, 1833. He was one of six children; one of his sisters married Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair, the influential Missouri Congressman. His father died in a mill accident on the family estate, and his mother went blind. Opposed to slavery, Mrs. Alexander freed her slaves and settled in St. Louis. Andrew attended Centre College in Danville, Kentucky and then returned to St. Louis, where he was engaged in business pursuits when war came in the spring of 1861.

Andrew Jonathan Alexander was born to a wealthy and influential family in Woodford County, Kentucky on November 21, 1833. He was one of six children; one of his sisters married Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair, the influential Missouri Congressman. His father died in a mill accident on the family estate, and his mother went blind. Opposed to slavery, Mrs. Alexander freed her slaves and settled in St. Louis. Andrew attended Centre College in Danville, Kentucky and then returned to St. Louis, where he was engaged in business pursuits when war came in the spring of 1861.

He was commissioned in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles as a second lieutenant on July 26, 1861. He was immediately promoted to first lieutenant the same day. The new lieutenant was assigned to serve on the staff of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, where he impressed the general with his efficiency. Alexander was appointed assistant adjutant general, serving first with McClellan, and later with Maj. Gen. George Stoneman.

He received brevets for gallantry for the 1862 Peninsula Campaign for carrying messages from McClellan to and from Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman under fire and for leading various scouting expeditions with the Union cavalry, for performing outstanding scouting and reconnaissance services before and during the Battle of Gettysburg, the Atlanta Campaign, and other engagements, eventually receiving a brevet to brigadier general of volunteers, dated March 13, 1865.

Originally assigned to the staff of Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, he joined Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s staff as assistant adjutant general of the Cavalry Corps when Stoneman took medical leave after the Battle of Chancellorsville. At the end of July, 1863, Stoneman became the first commander of the newly-formed Cavalry Bureau, an organization intended to provide remounts for the Union cavalry forces. Alexander went with him, serving on Stoneman’s staff at the Cavalry Bureau. On September 13, 1863, he was promoted to captain in the 3rd U. S. Cavalry (the successor designation of the Regiment of Mounted Rifles).

When John Buford contracted the typhoid fever that claimed his life, he went to Washington to recuperate, staying in Stoneman’s rented home. On December 16, 1863, the day Buford died, Alexander brought him a long-coveted prize: a major general’s commission. Buford, who was in and out of lucidity as the end drew near, had a lucid moment and said, “Too late. Now I wish I could live.” Alexander helped his fellow Kentuckian sign the commission.

In the spring of 1864, Stoneman was assigned to take command of a division of cavalry attached to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army. When Stoneman left, Alexander stayed on, joining the staff of his successor, Brig. Gen. James Harrison Wilson. Later that spring, Wilson assumed command of the 3rd Division, Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac, and Alexander went to join Stoneman’s staff once again. He served on Stoneman’s staff with Capt. Myles W. Keogh, a dashing Irish soldier of fortune who had loyally served Brig. Gen. John Buford until the dragoon’s untimely death on December 16, 1863. Alexander and Keogh developed a very close and lasting friendship that lasted until Keogh’s untimely death at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876 (Keogh and Alexander rest in the same cemetery in Auburn, NY). Alexander married Evelina Throup Martin on Nov. 3, 1864.

When Alexander returned to the army after his wedding, he joined Wilson’s staff as his chief of staff. Wilson, nominally Sherman’s chief of cavalry, was in the process of assembling a 15,000 man all-cavalry army that became a mounted juggernaut that served as the prototype for modern armored cavalry. Alexander performed especially valuable service in rounding up sufficient quality mounts for Wilson’s new army. Wilson urged Alexander’s promotion to full brigadier general of volunteers, but the war ended before that recommendation could be acted upon. However, he was brevetted colonel in the Regular Army by Grant.

On July 28, 1866, he was appointed senior major of the newly-formed 8th U. S. Cavalry and settled with his family at Camp McDowell, Arizona, where he and his wife had their first child, Emily. Commanding the Subdistrict of the Verde, Alexander scouted regularly against Apache Indians with the cooperation of the Pima Indians. He also contended with fights among residents of of nearby settlements.

In 1869, he was reassigned, commanding Camp Toll Gate until February 1870, when he went on leave. He rejoined the regiment in New Mexico. While commanding Fort Bayard in 1871, he was ordered to Fort Garland, Colorado at the direction of Sec. of War Belknap. He took leave in 1872 to tend to his ill wife after she had a miscarriage and then returned to duty in 1872, when he reported back to Fort Garland.

He was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 2nd Cavalry on March 20, 1879. In 1883, he began suffering serious health problems, including malaria, diabetes, and rheumatism. In 1884, he developed a bad inner ear infection and was retired as a full colonel as being unfit for further duty, effective July 3, 1885. His friends (including Generals Sherman and Stoneman) tried to arrange for him to be appointed deputy commander of the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C., but his health was too poor to permit him to perform the duties associated with the job. He spent much of his retirement writing about his war-time experiences and in maintaining a regular correspondence with Wilson, with whom he became close friends.

On May 4, 1887, while on a railroad train with his wife on their way to their home near Auburn, New York, he died suddenly and unexpectedly. He was a mere 54 years old. Alexander was buried in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, joining his dear friend Keogh there.

Maj. Gen. James Harrison Wilson wrote of him, “Those who had the fortune to know him during the war will readily recall and bear witness to his superb figure, his stately carriage, his bright, flashing blue eyes, his flowing beard as tawny as a lion’s mane, his splendid shoulders, his almost unequalled horsemanship…Standing over six feet in height, he was trim and commanding a figure as it was ever my good fortune to behold.”

Here’s to A. J. Alexander, a forgotten cavalryman who gave good service to his country both during the Civil War and in the years afterward.

Scridb filterEarlier today, there was some discussion on the Gettysburg Discussion Group about the role of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. By way of background: Brig. Gen. John Buford’s First Cavalry Division was ordered to leave Gettysburg and march to Maryland, where it would spend the rest of July 2 and all of July 3 guarding wagon trains and keeping the Army of the Potomac’s lines of supply, communications, and retreat open. By about noon, Buford’s two brigades had left the battlefield, leaving the left flank of the Army of the Potomac’s position in the air.

Responding to calls by Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield, the army’s chief of staff, to send additional cavalry to guard that flank, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, sent a single regiment, the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, to fill the role that had kept two brigades occupied for most of the morning. The question posed was what was the precise mission of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry on July 2, and when did it arrive on the Union flank.

As for the assignment, the 4th PA was supposed to provide screening for the left flank of the Army of the Potomac’s position. Butterfield’s note to Pleasonton of 12:50 states: “the patrols and pickets upon the Emmitsburg road must be kept on as long as our troops are in position.” OR 27, pt. 3, 490. A few minutes later, Butterfield wrote, “[Meade] expected, when Buford’s force was sent to Westminster, that a force should be sent to replace it, picketing and patrolling the Emmitsburg road.” Ibid. From these two dispatches, it’s clear that the 4th was supposed to perform the same duties that Col. William Gamble’s brigade of Buford’s division had been performing before it was pulled out.

As for the timing, I wrote this in an article that appeared in issue 37 of Gettysburg Magazine, in an article about the withdrawal of Buford’s division on July 2:

Gregg sent the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Its numbers were insufficient to cover the entire flank, and it is unclear when these men arrived in the area. The Pennsylvania horse soldiers had come to Gettysburg by way of Hanover after an all-night march, and they were exhausted. By the time they arrived, it was too little, too late, as Longstreet was about to unleash his sledgehammer blow on the Army of the Potomac’s left flank. It is unclear where the responsibility for the failure to replace Buford’s departing troopers lies, but it ultimately must fall upon the Cavalry Corps commander, Pleasonton, for failing to recognize the need to protect the army’s position with a cavalry screen. The Union left flank was left unprotected, leaving it open to the attack that would come that afternoon.

This paragraph appears on p. 71 of the magazine.

Lt. Col. William E. Doster of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry wrote in his after-action report of the battle: “At noon of the 2d of July, I was ordered to report with my regiment to Major-General Pleasonton, and was stationed in rear of a battery in the center of our line by a captain on General Pleasonton’s staff. Upon reporting to General Pleasonton in person, I was ordered to return to General Gregg, there being sufficient cavalry at that point, which was done.” (OR vol. 27, Pt 1, 1058-9).

He said more in his post-war memoirs:

…Gregg ordered us into a field of clover on Rock Creek, between Hanover and Taneytown roads. At three I was ordered to accompany a staff officer of General Pleasonton’s with my regiment. We hastened through the crowded roads to what I afterwards learned was Little Round Top, in rear of some artillery, McGilvery’s artillery brigade of Sickles’s corps, where I left my regiment and went with my guide to Pleasonton for instructions. This was the headquarters of our army.

The house was a small cottage on the left of the Taney Town Road, sheltered somewhat by the hill above. Outside were many staff officers and orderlies. Within was Butterfield, Meade, and Pleasonton. They occupied a room that contained the ordinary bedroom furniture of an ordinary Pennsylvania farmer. Their gentlemanly manner and brilliant uniforms contrasted strangely with the surroundings.

Pleasonton begged my pardon for having made me ride so far. There was no need of exposing the cavalry in front. I should rejoin Gregg on the right and tell him to take good care of it. My orderly’s horse was struck by a shell here. I rejoined my regiment, who were very glad to get out of the fearful rain of shell which, directed to the caissons in front of them, dismounted a number of them. On my way back noticed Sickles on a stretcher, smoking a cigar. They said his leg had been shot off in the last charge. This is giving the ‘Solace Tobacco’ a new meaning. By the time I reached Gregg he was just going into camp in the clover field above mentioned. The men were just leaving their horses to run at random to graze and sitting down to make coffee, when a long Rebel infantry skirmish line issues from the woods and advances towards us, while artillery on the edge of the woods reach us with shells. We get our artillery limbered up again, throw out a stronger line, drive them back, and then, in sight of one another, take supper, for the first time since we left Edwards Ferry, with some degree of comfort…..

Thus, the answer is that this lone regiment arrived as Longstreet’s assault was getting ready to step off, far too little and far too late to make any difference at all. Then, the Pennsylvanians were pulled back out of line and sent to re-join the rest of Gregg’s division. They played no role at all in the repulse of Longstreet’s assault.

It’s an interesting question as to what Pleasonton really hoped to accomplish, and also why he failed to send a proper force to screen the left flank in a timely fashion. Had he done so, it’s entirely possible that Sickles would not have moved his 3rd Corps out to the Emmitsburg Road plateau, where his command fought valiantly, but was largely sacrificed to Longstreet’s blow. Pleasonton never said, so we will never know. It’s just one of many egregious failures by him during the Campaign, and undoubtedly the most costly in terms of human life.

Scridb filterMy old friend Andy German, who is THE authority on all things 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, left a really outstanding comment to my post on George D. Bayard. So good, in fact, that I decided to feature it here:

Hello Eric,

I’m just catching up with your posts. It’s great to give Bayard his due. From my work on the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, he’s an old friend. It’s true that his volunteer troopers initially hated him for his strict discipline–and he knew that some had threatened to shoot him the first time they got to fire on the enemy–but after that first winter of instruction they had complete confidence in him. At a time when the federal cavalry in the east was trying to find its footing, he pushed his command and they met expectations. You mentioned the reconnaissance at Falmouth, which was actually a night attack to secure the bridge, thwarted by an ambush. At the end of May, Bayard’s “Flying Brigade” (which included a battalion of the “Bucktails” (riflemen) and a battery of mountain howitzers) reconnoitered far south of Fredericksburg, then immediately turned around and marched to the Valley, catching the end of Jackson’s column at Strasburg before Fremont’s command finished its much shorter march to complete the pincer movement. Then the cavalry led the federal advance through the rain, fighting aggressively with Jackson’s rear guard. You even see dismounted tactics employed here.

Under Pope, Bayard and Buford acted independently but supportively. Bayard’s fighting withdrawal from the Rapidan slowed Jackson’s advance by a day and permitted Pope to get into position at Cedar Mountain. There, Bayard sacrificed one battalion of his 1st Pennsylvania in a mounted charge against infantry. Later, as the Army of Virginia withdrew across the Rappahannock, Bayard conducted a successful mounted engagement with Confederate cavalry–a mini Brandy Station I. His troops then held Thorofare Gap against Longstreet and during Second Manassas maintained a cavalry presence on the left flank, prepared for a night cavalry charge in the center, and held the rear during the retreat to Centreville.

He remained in command of the cavalry in front of DC during the Antietam Campaign, but conducted scouts as far as Warrenton and proposed a mounted raid not unlike Stoneman’s Raid of six months later. As mentioned, his brigade joined the AoP at the beginning of November, and Pleasonton was not happy to be outranked by such a young officer. Bayard’s brigade performed well at Aldie, at Warrenton, and in the night seizure of the bridge at Rappahannock Station. At Fredericksburg, his brigade in the Left Grand Division was the only cavalry engaged. On the day before the battle they felt out the Confederate position and skirmished sharply with Confederate infantry along the railroad. After Pelham’s artillery flank attack, the 1st Pennsylvania was deployed to picket the left flank and sat on horseback all day under artillery fire. The rest of the brigade remained near Franklin’s headquarters, where Bayard was mortally wounded. It was speculated that a bolt from the Confederate Whitworth gun did the deed as the range was too great for conventional artillery. What a sad fluke.

Bayard’s death was a great loss, and his men found they missed his leadership greatly. They came to appreciate David Gregg’s fatherly leadership, and would do anything for him, but Gregg didn’t have the dash of Bayard. We can’t know for sure, but I’d say Bayard would have made a great division commander. His confidence in the mounted arm and comfort in independent command probably would have made him support the cavalry corps concept. Whether he would have suffered some of the fools in command and been able to manage the whole show is an intriguing question.

Thanks,

Andy German

Thanks for the input, Andy.

Scridb filterIt’s been quite a while since I profiled a forgotten cavalryman, so I think it’s time to do so again. Today’s subject is Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard.

Bayard was born on December 18, 1835 at Seneca Falls, New York. He was a direct, linear descendant of the family of Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard, known as “the Good Knight”. Chevalier Bayard was also called “the knight without fear and without reproach.” George’s great-grandfather had commanded the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Revolutionary War, so cavalry was in the boy’s blood. When he was 8 years old, the family moved to Iowa for several years. In 1849, the family returned and settled in New Jersey. In 1852, young George was appointed a cadet at large in the Military Academy at West Point by President Millard Fillmore. He graduated in 1856, standing eleventh in a class which originally numbered ninety members. On leaving the Academy, he chose the cavalry arm of the service, and was assigned to duty with the 1st U. S. Cavalry (now the 4th U.S. Cavalry), rising to the rank of captain.

Not long after he joined the regiment, the 1st U.S. Cavalry, was ordered to the plains, where it had frequent encounters with the Indians. In 1860, while engaged with a party of Kiowas, Bayard was severely wounded. His father gave the following account of this event: “After a pursuit of more than twenty miles; some Indians were seen at a distance. Lieutenant Bayard, being mounted on a superior horse, whose speed surpassed that of any in the command, led the way in the chase. He soon came up with an Indian warrior, and, presenting his revolver, demanded his surrender. The Indian, as Lieutenant Bayard rode up to him, had dismounted from his pony for the purpose of dodging the shot from the pistol he anticipated, or to enable him the better to use his bow and arrow. At this moment, while in this attitude, Lieutenant Bayard saw some Indians running at a distance, and turned to see if any of his men were near enough to receive a signal from him that other Indians were in sight, and as he turned again towards the chief he had brought to bay, the latter shot him with his arrow. The arrow was steel-headed, in shape like a spear-head, and the head two and a half inches long. It struck Lieutenant Bayard under the cheek-bone, and penetrated the antrim. If the Indian had not been so near, he would have drawn his bow more taut, and probably killed his enemy.”

The arrow head was imbedded so firmly in the bone that it could not safely be removed except by superior skill. Though enduring intense suffering, Bayard made a journey of 800 miles to St. Louis before he could have the operation performed. Its removal gave some relief, but the wound did not heal, and he was subject to severe hemorrhage which threatened his life. The artery, which had been severed, was cauterized, freeing him from further danger, and he was soon after assigned to duty as cavalry instructor at West Point.

When the war broke out in 1861, even though his wound was still unhealed and very painful, he repeatedly asked to be relieved, and allowed to join a regiment of volunteers. In a letter to his father of April 13, 1861, he wrote: “The capital will very soon be the object of attack, and I think it the duty of all good Americans to march to its defence. My heart is too full to write you anything about Sumter. The Southerners have made a great mistake attacking it. All my sympathy with the South is now gone. It is now war to the knife.” And again, on July 26, 1861 he wrote, “I must go to this war. I cannot stay here and rust while gallant men are in the field. This Rebellion is a much more serious thing than many suppose. I pity the Southern officers in our army. They cannot but condemn the madness of their politicians who have brought on this war, and yet they feel in honor bound to go with their section.”

Finally, his request to be relieved of duty at West Point was granted in September 1861, when he was made major of a newly recruited regiment pf New York cavalry. On his arrival at Washington, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, then commander-in-chief, would not consent to his taking this position, and instead gave him the option to take command of a regiment or to serve as an aid upon his staff. Bayard chose an independent command, and was appointed colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry, which was part of the Pennsylvania Reserves, by Keystone State Governor Andrew G. Curtin. He quickly became known as a martinet, and he was not especially popular with the men who served under him. His first speech to his men, delivered as they were about to undertake a hazardous duty, was characteristic: “Men! I will ask you to go in no place but where I lead.”

A friend left this description: “As a soldier, in camp and on the field, in bivouac or in the height of an engagement, he was a perfect model. He had a quiet but keen eye, detecting and correcting what was wrong, and just as quick to discern merit. In the field, he participated in all the hardships with the men, declining a shelter when they were exposed.” During a reconnaissance of Confederate-held bridges outside Falmouth, Virginia, he came under attack, and rifle fire hit his horse three times. He survived the engagement unharmed, and was commissioned Chief of Cavalry of the III Corps and brigadier general of volunteers on April 28, 1862.

When McClellan went to the Peninsula, Bayard remained with the army of observation before Washington. At Cross Keys, and all the subsequent operations under Maj. Gen. John Pope, he acquitted himself with great credit, capably commanding a brigade assigned to Pope’s Army of Virginia. He had been at the Academy with J. E. B. Stuart, and at Cedar Mountain they met; first in conflict, and afterwards under flag of truce for the burial of the dead, where they conversed in a friendly way. No allusion was made to the present war, but they talked of former associations. “During the interview,” says a Washington paper, “a wounded Union soldier lying near was groaning and asked for water. ‘Here, Jeb,’ said Bayard – old time recollections making him familiar as he tossed his bridle to the rebel officer – ‘hold my horse a minute, will you, till I fetch that poor fellow some water.’ Jeb held the bridle. Bayard went to a stream and brought the wounded man some water. As Bayard mounted his horse, Jeb remarked that it was the first time he had ‘played orderly to a Union General.'” Stuart was then a major general in the Confederate service. The business for which they met was soon arranged, and when the bugle sounded the recall, they shook hands and turned away, mortal enemies again.

Despite the disfiguring wound, Bayard was engaged to be married. The wedding was scheduled for his 27th birthday, December 18, 1862. That fall, as the senior cavalry officer, he took the field with the Army of the Potomac. “I have been troubled a good deal of late with rheumatism, owing to having been thoroughly drenched with rain,” he wrote to his father on November 22. “I ought to be in the hospital. But I must go with this army through. I am senior General of cavalry. Honor and glory are before me – shame lurks in the rear. It looks as if I should not be able to leave at the time appointed for my marriage, but will have to postpone it till this campaign is over.”

His cavalry opened the December 13, 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, holding the enemy in check until the infantry could come up, when he was withdrawn and posted on the extreme left of the line, his left flank abutting upon the river. His command spent the morning of December 13 more or less with the enemy’s skirmishers and advance. His last directions, before leaving his troops to go to the headquarters of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, who commanded the Right Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac, were given to his artillery officer to change the position of some of his guns. Bayard then rode off to see Franklin.

“A little before two o’clock he rode to headquarters, to receive such orders as General Franklin might deem proper to give. He found the General in a grove of trees, with some of his staff and other General officers. The enemy were then throwing their shells at and around this grove. General Bayard, soon after he arrived, having dismounted, seated himself at the foot of a tree, but with his face towards the quarter from whence the shells came. He was warned by a brother officer of his needless exposure, and invited to change his position. This he did not do, but remained for some time participating in the conversation of those around. In a little while, however, he rose from his seat, and hardly stood erect, when he was struck by a shell just below the hip, shattering his thigh near the joint. In this frightful condition, with mind still clear and active, he lingered until noon of the following day, arranging his business and sending messages of love and affection to friends.” He dictated a brief note to his parents: “I have to dictate to you a few words, ere it becomes too late. My strength is rapidly wasting away. Goodbye, dearest father and mother; give my love to my sisters.”

He did not appear to suffer much pain, and about 24 hours after being struck, quietly died just five days before his 27th birthday. “Not one,” wrote Horace Greeley, “died more lamented than Major-General George D. Bayard, commanding our cavalry on the left, who was struck by a shell and mortally wounded. But twenty-seven years old, and on the eve of marriage, his death fell like a pall on many loving hearts.” He was buried in Princeton Cemetery in Princeton, New Jersey.

Bayard was the senior officer in the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry at the time of his death. Although Maj. Gen. George Stoneman would have been entitled to command of the Cavalry Corps at the time of its formation in February 1863, Bayard would have been the senior division commander. Thus, when Stoneman took medical leave on May 15, 1863, Bayard would have assumed command of the Cavalry Corps, and not Alfred Pleasonton. The complexion of cavalry operations would have been very different indeed, and it is intriguing to consider what effect Bayard might have had on the evolution of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps had he lived.

Scridb filterLast night, in order to answer a question that someone sent via e-mail, I pulled out the H. E. Howard regimental history of the 16th Virginia Cavalry. After checking the roster to answer the question I’d been asked, I decided to have a look to see what the book might have about Monocacy, as the 16th Virginia was part of McCausland’s Brigade, which fought all day at Monocacy on July 9, 1864. There’s not much, a couple of paragraphs. However, there was a map that caught my eye.

This map indicated that there was a skirmish on July 7 between the men of McCausland’s Brigade and troopers of the 4th U.S. Cavalry at Hagerstown, after which the town was ransomed. This really puzzled me–not because the town was ransomed; I already knew that–but because I was completely unaware of there being any troopers of the 4th U. S. Cavalry still in the Eastern Theater in July 1864. So far as I knew, the entire regiment was serving in Col. Robert H. G. Minty’s brigade in the Army of the Cumberland as of that date. The histories of the other two regiments of McCausland’s brigade–the 14th and 17th Virginia Cavalry regiments–had the same map and even less detail in the narrative.

Consequently, I sent Don Caughey an e-mail asking him if he knew anything about this. Don’s done a great deal of work on the 4th U. S. Cavalry with the thought of a book project, so I figured that if anyone would know, it would be Don. Don wrote back and confirmed what I thought–the regiment was serving in the Western Theater. That, I thought, was that–another example of poor scholarship and poor fact checking in one of the H. E. Howard regimental histories.

Today, J.D. was going through some copies of some documents from the Cavalry Bureau that he’d gotten, and sure enough, he found a letter dated June 22, 1864, by a captain of the 4th U. S. Cavalry, discussing how the large detachment of dismounted cavalrymen from the Army of the Potomac that had accumulated during Grant’s Overland Campaign had been sent to Julius Stahel in the Shenandoah Valley to operate against Early.

So, I’m left with the fascinating question of just who these guys were that McCausland tangled with at Hagerstown on July 7, 1864. I suspect that this is going to be a difficult question to answer, so if any of you have any ideas, I’m more than happy to hear them. Please feel free to pass them along.

Scridb filterIt’s been a while since I’ve profiled a forgotten cavalryman, so I thought it was high time that I did so.

Bvt. Brig. Gen. William Emile Doster was born on January 8, 1837, at the Moravian town of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His father, Lewis Doster, a native of Swabia, Germany, served a campaign against Napoleon, and emigrated to America with his father, Doctor Daniel Doster, in 1817, at the age of twenty. His mother, Pauline Louise (Eggert) Doster, was the daughter of Matthew Eggert, at one time Vorsteher of the Brethren’s House, and granddaughter of Adam Rupert, a soldier of the Revolution. His father owned and operated the successful Moravian Woolen Mills in Bethlehem.

As a child, he preferred drawing and painting, but as the seventh son, as his grandfather before him had been, he appeared destined for the profession of medicine. However, he did not like medicine or have any interest in pursuing it as a career. William attended the Moravian school until the age of fourteen, and after a careful preparatory training entered the sophomore class of Yale College, graduating in 1857. In 1859 he graduated as LL.B. at the Harvard Law School. In 1860 he matriculated as student of civil law, in the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and heard lectures on the Code Napoleon in Paris.

Upon his return home he apprenticed with ex-Governor Andrew H. Reeder, at Easton, and was admitted to practice at the Northampton County bar. Aside from fencing and riding, taught in the European universities, he had no military training.

When the war broke out he was in the office of S. Van Sant, of Philadelphia, but putting aside briefs and black letter-books, he responded to the President’s call for volunteers, and recruited a company of cavalry, which, not being wanted for that arm, was turned over to Colonel Edward D. Baker’s infantry regiment. Doster then raised another company for Harlan’s Light cavalry, of which he was made Captain, his muster bearing a date of August 15th, 1861. A few weeks later this company was transferred to the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

On October the 28th of October he was promoted to Major, and a little more than a month later, was detailed with a squadron to act as bodyguard to General Erasmus Keyes.

Toward the close of February, 1862, he was placed in command of the mounted provost guard of Washington, D. C. When the Army of the Potomac departed for the Peninsula, and the appointment of General James S. Wadsworth as Military Governor of the District, Colonel Doster was selected for Provost Marshal, giving him command, by detachment, of four infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment, together with a flotilla cruising upon the Chesapeake.

In October, 1862, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, but continued at his post as Provost Marshal. Just previous to the opening of the spring campaign of 1863, he applied for an order to return to his regiment, which was granted, and was coupled with a recommendation from General Wadsworth to President Lincoln, for his appointment as Brigadier General. On rejoining his regiment he assumed command, and led it during the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns. He had his horse shot under him at Ely’s Ford, and in a charge which he led at Upperville, was taken prisoner. However, in less than an hour, Doster escaped by striking down his guard and returned to his command.

At Gettysburg he was ordered to report with his regiment to General Pleasanton, at General Meade’s headquarters. On the afternoon of July 2, the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry was the only regiment sent to take position on the Federal left flank, meaning that one regiment was supposed to provide the same coverage as the provided by two brigades of Brig. Gen. John Buford’s division. That evening, Doster was ordered to picket duty on the left flank, and established a line in front of the infantry at eleven o’clock that night. On July 5th, he was ordered to advance through Gettysburg in pursuit of the enemy.

Tearing aside the barricades that obstructed the way, he pushed on as far as Stevens’ Furnace, where he engaged the rebel rear guard. By the evening of the 6th, he had reached Marion, near Greencastle, where he struck Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry. After a severe action brought on by reconnoitering towards Winchester, he led his regiment back to the Rappahannock, where he was prostrated by malaria. Too ill to return to duty, he sent in his resignation, which was accepted. He returned home to Easton and was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar. However, soon after, he was appointed colonel of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry, but never joined the regiment. He was subsequently brevetted brigadier general of volunteers.

Doster practiced law in Washington for a short time, and at the trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, he was appointed, by Judge-Advocate-Generals Hold and Bingham, to defend Lewis Payne and George Atzerodt, two of the defendants. Both were convicted and hanged.

Soon after the close of the war he returned to Northampton County and resumed the practice of the law at Easton, residing at Bethlehem. From 1867-1879, he held the office of Register in Bankruptcy for the Eleventh Congressional District. He was also the long-time president of the Lehigh National Bank and also of the New Bridge Street Company.

On August 15, 1867, he married Evelyn A. Depew, daughter of Edward A. Depew, of Easton. They had one son. The couple settled in Bethlehem in 1873. Doster traveled to Europe more than 30 times in the years after the Civil War.

In 1891, Doster published his Brief History of the Fourth Pennsylvania Cavalry, following it in 1915 with his memoirs, Lincoln And Episodes Of The Civil War.

Doster died on July 2, 1919, and was buried in Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like