Category:

Battlefield stomping

Yesterday finally ended three weeks of insanity.

On Friday morning, I hit the road for Virginia, headed for Culpeper. It’s nearly 435 miles each way, and it’s a LONG drive. I reached the Graffiti House at Brandy Station about 3:30, and then spent the next 90 minutes laying out a driving tour for my Brandy Station book, including shooting GPS coordinates for the stops on the tour (I ended up shooting 36 of them). I then went and checked into my hotel, had dinner in the hotel restaurant, and spent the evening watching the Pens beat the big, bad Red Wings to bring Lord Stanley’s Cup home to Pittsburgh. It was really pretty remarkable.

Last summer, I auctioned off a two-day tour as a fundraiser for battlefield preservation, and this weekend was time to deliver the goods. That’s why I made the trip. Saturday, with the help of Mike Block, who is a member of the board of trustees of the Brandy Station Foundation, who came along to help me lead the tour, we covered the Battles of Kelly’s Ford and Brandy Station in detail. We finished at the National Cemetery in Culpeper. This is now the second time that Mike and I have done this dog-and-pony show, and we really work together well. I really enjoy doing tours with him.

I was also fortunate enough to have Prof. Chris Stowe, who teaches at the Army Command and General Staff College’s branch campus at Fort Lee in Petersburg, VA, along. Chris is working on George Gordon Meade’s papers, and he is extremely knowledgeable. Finally, I had the opportunity to have Tim Ferry and Lance Williams along, and we had a great day. After a long, hot day, I then had dinner with old friend Melissa Delcour at a terrific Italian place in Culpeper called Luigi’s that I highly recommend.

The Brandy Station battlefield looks great, with the exception of the hideous McMansion that was built on the crest of Fleetwood Hill. We saw pretty much the whole field, although we didn’t hike out to the stone wall on the Cunningham farm. The ground was too soggy, and there would have been too many snakes and too many mosquitoes out there, and I made the command decision not to expose ourselves to it.

On Sunday, I took Chris, Tim, and the four fellows who won the tour to Trevilian Station. We drove the 45 miles down, toured the battlefield–none had been there previously–and then I took Tim and one of the others back to the Graffiti House, where they had left their cars. While I didn’t go off into the woods to look at the property–no time for that–I was able to confirm that the parcel of property that is going to be the subject of the CWPT’s next fundraising campaign is a key parcel because it connects the first and second days’ battlefields with a pristine parcel to make that link. It’s a pristine, 250-acre parcel that was part of the farm that was a major portion of the second day’s battlefield that was called the Gentry farm in 1864.

I then had to drive home. I left at 3:00, and got home at nearly 9:45. With the trip to Trevilians, I drove about 550 miles yesterday while making the banzai run. By the time I got home, I was completely exhausted, and I am still tired now, even after a decent night’s sleep in my own bed last night.

There’s nothing I love more than battlefield stomping, but after three straight weekends of leading tours and too much driving, I am worn out. I’m thrilled at the prospect of actually being home this weekend for a change. I also haven’t had a chance to see stuff I want to see because I’ve been leading tours non-stop. It would be nice to see something new while having someone else lead the tour for a change.

Anyway, that’s it for the banzai runs for now. I have a talk to the Western Pennsylvania Civil War Roundtable on Wednesday night, and then nothing again until October. It’s going to be a nice break. In the meantime, if any of my readers are in the Pittsburgh area, I hope you can make the talk on Wednesday night.

Scridb filterAt 4:30 on Wednesday afternoon, as I was busily working on a draft of a complaint, my laptop suddenly locked up. When I tried to reboot it, it would not boot; the hard drive just made a clicking noise, and I came to the incredibly unhappy realization that I had suffered the same hard drive crash that my wife had suffered 13 days earlier. Apparently, the Fujitsu hard drives that Apple was using at the time (and Sony, too) are prone to zero-sector damages, which lead to crashes.

Of course, my whole life is on that computer. Most of the important stuff had a recent back-up done, but I still panicked. Anything that was sone since the back-up the week before would be lost, and there was a lot of work done during that period of time.

Luckily, everything will be recoverable. I should have it all back early next week. WE went and bought a new 2.5 inch drive for the laptop–Western Digital this time–and it was installed today. The old drive was 120GB, while the new one is 250GB, so I am better than doubling drive capacity. And the best part was that drives have come down so much that it cost me $79.99 for the new drive.

I am using our back-up laptop as I write this. It’s something like 6 years old, and it was the forebear to netbooks. Susan calls it the tiny laptop, for good reason. It weighs like 3 pounds and has a 10-inch screen. However, unlike netbooks, this is a full Pentium II processor running Windows XP, and it will do until I get my machine back Sunday when I get home.

All things considered, it could have been MUCH worse. However, as I told Susan yesterday, I feel like Linus from Peanuts does when he can’t find his security blanket.

I spent the afternoon today laying out the driving tour of the Brandy Station battlefield for my upcoming book, including adding GPS coordinates. I only addressed the publicly accessible portions of the battlefield; the Yew Ridge portion of the battlefield is entirely in private hands, and I have too much respect for the property owners to turn tourists loose on their property.

The battlefield is still beautiful, and I’m so grateful that I know it well enough to be able to lead tours there. I’m leading a tour of Kelly’s Ford and Brandy Station tomorrow and of Trevilian Station on Sunday before making the banzai run home Sunday.

Like I said, all things considered, it could be much, much worse.

Scridb filterTomorrow begins my crazy travel schedule. Tomorrow, it’s off to Gettysburg for the annual muster of the Civil War Discussion Group Online, and a retreat tour on Saturday. We come home Sunday (Susan’s going with me on this one), and then it’s back to Gettysburg again next Friday for the annual conference of the CWPT, where I have a full day tour to lead. Then, we’re off to Middleburg, VA on Sunday night for a memorial for our friend Deborah Fitts, and then home to Columbus on Monday morning. I leave again that Friday, this time for Brandy Station and Trevilian Station, to fulfill a commitment I made last year, when I auctioned off a personal tour to raise money for the CWPT at one of Ted Alexander’s Chambersburg Civil War Seminars.

The good news is that these events will provide lots of opportunities to see friends I haven’t seen in quite a while, including Clark B. “Bud” Hall, whom I haven’t seen since he lost Deb last July. Seeing old friends will make all of the driving worthwhile.

So, it’s going to be a busy next couple of weeks with way too much driving. I will post when I can, but don’t be surprised if postings are a bit sparse until I get through this craziness.

Scridb filterFrom yesterday’s edition of The Gettysburg Times:

Electric Map may have found a home

BY SCOT ANDREW PITZER

Times Staff Writer

Published: Tuesday, May 12, 2009 7:40 AM EDTA nonprofit group is working with the National Park Service to keep the historic Electric Map in Gettysburg.

Historic Gettysburg-Adams County is talking to the park about obtaining the map and featuring it in a new museum, possibly along Steinwehr Avenue.

“It’s quite possible that it could be coming out of storage,†HGAC President Curt Musselman said Monday morning.

Musselman was the guest of broadcaster Fred Snyder during the Breakfast Nook program on 1320 WGET.

Musselman’s group has been working to obtain the map for “about a year,†and the group has set up a task force to acquire it.

“We’re going to build a museum — a map museum — making the Electric Map a centerpiece for that,†said Judi McGee, chairwoman of the HGAC task force.

“The map itself will be restored,†McGee said. “We’ll also be able to preserve and restore some other period maps along the way and some artifacts.â€

She promised that the map will be staying in the Borough of Gettysburg, although she did not name specific sites.

“We’re looking at an adaptive re-use of an old building,†McGee told Snyder. “We’re also looking at building something new. We’re looking at a number of sites.â€

Steinwehr Avenue businessman Eric Uberman said Monday that he has land beside his American Civil War Museum to accommodate the group. He called the property an “optimum site†for the Electric Map.

“We’re cooperating with them — we’re not buying the map,†said Uberman.

“We have the space,†continued Uberman. “It’s the spot that has the most visibility, it’s in Gettysburg, and it’s literally right where the map was before.â€

Gettysburg National Military Park spokeswoman Katie Lawhon confirmed Monday afternoon that the park is talking to the group, but stressed that “it’s very early in the process.†The park has entertained offers for the map in the past, but nothing panned out.

“Their goals would certainly be in sync with the Park Service’s goals, which would be to display the Electric Map once again to the visiting public,†said Lawhon. “The goal is to work cooperatively and re-open it to the public.â€

Uberman’s property is located across the street from the entrance to the old visitor center. He thinks that the map would “do wonders†in revitalizing Steinwehr Avenue, which has seen a dramatic drop-off in commerce since the old visitor center closed.

“It would be a tremendous boost to Steinwehr,†said Uberman. “I really hope that the town fathers support this group. It would be a tremendous tax benefit to the area, and maybe pull back some of the revenue that has been lost since the new visitor center opened.â€

The map was cut into four pieces in March and moved out of the old park visitor center. It is now being stored in a park facility along the Hanover Road, just east of Gettysburg. The map was not incorporated into the plans for the new $103 million Battlefield Visitor Center, which opened in April 2008 along the Baltimore Pike.

“I just think in their new design, the Electric Map didn’t fit in,†Musselman said. “Some day again, people will be able to see it.â€

McGee noted that “there are some issues there with asbestos and construction that we need to address,†and that talks are ongoing between the federal government and HGAC.

HGAC has worked with the Park Service on other projects, said Musselman. The group is aiming to have the map on display again in time for the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which occurs in 2013.

“That would sort of be the time-line on the project, so don’t hold your breath waiting for it to happen,†Musselman said. “Everything would take time. It’s not just a little project.â€

The map entertained millions of tourists over the years, when it was the park’s primary attraction. It used 625 flashing Christmas bulbs to illustrate the movement of troops during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Opponents argue that the map’s technology is obsolete, while proponents believe that it’s an iconic American treasure.

The current map dates back to 1962-63, although the original map dates back to the 1930s.

See the complete transcript of the Breakfast Nook interview by visiting www.gettysburgtimes.com/blogs.

There’s absolutely no doubt that the technology of the Electric Map has been obsolete for years. At the same time, it’s been the first introduction to the Battle of Gettysburg for hundreds of thousands of tourists for decades, and that many have very happy memories of it. There’s also no doubt that it’s been missed by tens of thousands of tourists, including me. I also think that it would help to bring tourists back to Steinwehr Avenue, which would definitely benefit the local businesses. I view this as a real win-win scenario.

I certainly hope that this pans out and that the Map finds a home. Even if it is obsolete, it should be on display and it should be available for the world to see. I support it wholeheartedly.

Scridb filterFrom the current issue of National Journal, we have the following article on John Latschar’s reign at Gettysburg:

LINCOLN BICENTENNIAL

A New Battle Rages At Gettysburg

Gettysburg National Military Park had a $103 million makeover, but conflict at the iconic site continues.

by Edward T. Pound

Saturday, Feb. 21, 2009GETTYSBURG, Pa. — In August 1994, John A. Latschar arrived here to take over as superintendent of the Gettysburg National Military Park, site of the most momentous battle of the Civil War. The longtime National Park Service ranger and decorated Vietnam veteran was appalled by what he saw: a battlefield in need of restoration; a 307-foot, privately owned tourist observation tower, widely reviled, looming over the Soldiers’ National Cemetery where Union soldiers were laid to rest and where President Lincoln delivered his immortal address in 1863; and a musty museum and visitor center that had seen far better days.

In the ensuing years, he began restoring important landscapes and led the Park Service’s effort to demolish the eyesore of the so-called National Tower, which was done in July 2000 and highly praised by the preservation community. He also set in motion plans for a new state-of-the-art museum and visitor center, using a partnership consisting of a private, nonprofit foundation and the Park Service.

As it turned out, that partnership venture became one of the most important arrangements in the Park Service system, which is always hard-pressed for cash. The new facility finally opened in April. A few months later, during a visit to the park, then — Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne called Latschar “a national treasure.”

A pretty rosy picture, to be sure. But the reality is a bit more complicated.

Latschar’s tenure at Gettysburg has been marked by repeated conflicts with some Civil War preservationists and others aghast at the mammoth size of the new museum-visitor center and by what they see as the lack of government supervision of the project and the Gettysburg Foundation, the Park Service’s controversial nonprofit partner. His plans for the park have led to clashes with battlefield guides, with local businesses, and with the family that contributed a famed collection of 38,000 artifacts to the park.

Now 61, Latschar gets things done. He is known within the Park Service for his “can-do” reputation — he loathes rules that get in the way — his mental toughness, and his ability to forge close relationships with higher-ups. But that tenacity can be a two-edged sword. To critics, he is someone more than willing to run over people who get in his way.

Behind the scenes, after Park Service staffers in Washington raised concerns in 2003 that a 139,000-square-foot museum and visitor center was too large and too expensive, Latschar went around them to a senior agency official who arranged a meeting with the director of the Park Service. The staffers were reprimanded, and a Park Service board swiftly approved the project’s comprehensive design, according to Latschar’s account of the incident. Without the approval, the project would have been delayed and might have required downsizing.

As the nation celebrates the 200th birthday of Abraham Lincoln this month, the long-running conflict at Gettysburg isn’t likely to end anytime soon. The heart of the conflict, to critics, boils down to this: promises made, promises not kept.

The museum-visitor center project initially carried a price tag of $39.3 million. In the end, it cost $103 million. While selling the public on its public-private partnership idea, the Park Service repeatedly maintained that the project would not need federal monies and would be financed solely with private donations, corporate sponsorships, and loans. That isn’t quite what happened. Over the years, Congress earmarked $15 million for the project — Rep. John Murtha, D-Pa., arguably the king of pork on Capitol Hill, arranged the funding — and the state of Pennsylvania tossed in another $20 million.

And from the get-go, Park Service and Gettysburg Foundation officials did not envision charging an admission fee for visitors to view the museum’s exhibits and collection of world-famous artifacts. But only six months after opening the center in April and projecting an annual revenue shortfall of nearly $1.8 million, officials imposed an admission fee of $7.50. The “all-in-one” fee also allows visitors to view other park attractions. But as one critic of the new policy pointedly noted at a public meeting, according to The Gettysburg Times, “it would take 52,364 people paying $7.50 just to pay” the foundation president’s annual salary of $392,735.

Meanwhile, Latschar’s conduct has come under government scrutiny. Investigators from the Interior Department, which includes the Park Service, are reviewing, among other issues, whether he misused $8,700 in funds from the park and a private group for construction of a fence on 4 acres of parkland -adjacent to his home. His wife, Terry, uses the pasture to exercise her horses under a park permit. In an interview, Latschar said he was confident that investigators would determine that he did nothing improper.

Although the inquiry’s breadth is unclear, the investigators from Inspector General Earl Devaney’s office also contacted the Gettysburg Foundation; they didn’t question anyone and were provided with a list of contractors on the museum-visitor center project, according to foundation officials. Investigators declined to comment.

Latschar has faced other ethics issues as well. Last November, after announcing he would retire from the Park Service and take over the lucrative presidency of the Gettysburg Foundation, critics accused him of a conflict of interest. They cited his extensive dealings with the foundation as Gettysburg’s superintendent. Indeed, Latschar played an important role in planning the museum project and in the agreements that the Park Service struck with the foundation to operate the facility. Interior Department lawyers, in an opinion issued last month, strongly suggested that moving over to the foundation would constitute a conflict. Latschar decided to stay in his government position.

High-Profile Partners

For many Americans, Gettysburg is sacred ground. Established in 1895, the 5,900-acre park 80 miles north of Washington remains a popular attraction; last year, about 1.5 million visitors viewed the ornate monuments and historical exhibits, walked the open ground, and climbed the stony hills where, on the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg unfolded in the pivotal clash of the Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army, seeking a decisive victory on Northern soil, was defeated by Union forces in a bloodbath that left 51,000 soldiers dead and wounded. In November, President Lincoln delivered his 272-word Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

Gettysburg’s public-private partnership experiment is a model that other parks can use to preserve and improve resources and facilities, officials explained. The reason for the partnership is pretty straightforward: Much like a beggar on the street, the National Park Service needs money. Created in 1916, the agency has an annual budget of only $2.5 billion, a pittance considering it must manage and maintain some of the nation’s most precious assets — 391 parks, including 24 Civil War sites. The Park Service also has a staggering deferred-maintenance backlog of nearly $9 billion in projects.

In speeches drumming up public support for the Gettysburg partnership, Latschar described the Park Service’s problems succinctly: “Why are we broke? Most simply stated, both Congress and the American public are in a love affair with national parks — but are not willing to pay for the consequences of their devotion.”

As the Park Service declares on its website, public-private partnerships are “a way to get things done.” The chief of the agency’s partnership program, John Piltzecker, said in an e-mail response to National Journal’s questions that “there have been numerous instances of partners raising all or part of the funds needed to help the [Park Service] accomplish its mission, whether it was a new or improved facility, the rehabilitation of a trail system, or the enrichment of park programming.” These partners include nonprofits, companies, and volunteers.

The way Latschar and Gettysburg Foundation officials see it, the partnership has been an unmitigated success and a good deal for the public. Latschar’s many critics don’t agree. “Let me put it as simply as I can,” said Franklin Silbey, a former congressional investigator, a Civil War preservationist, and a longtime thorn in Latschar’s side. “Latschar and the Park Service have repeatedly misled the public. The new museum costs three times more than it was supposed to. They said they didn’t need federal funds, yet they got $15 million in federal earmarks. The old museum and its artifacts used to be free. Now the public has to pay $7.50 a head just to walk in the museum door. A for-profit vendor sells trinkets on sacred ground. Need I say more?”

In a three-and-a-half-hour interview at his offices in the new facility, Latschar said he has always been truthful with the public. “From the very first speech on this project in January, February 1995 to today, I have never misled the public about a single thing. Everything that I’ve ever said has been based upon the best [information] that I knew and the best I believed at the time. It turned out in a couple cases that what I believed didn’t happen the way we thought it would, but there’s been absolutely no deceit involved.”

Latschar, who has a Ph.D. in American history, said he enjoys wide support among Civil War historians, preservationists, and local business leaders. They understand, he said, that a desire to protect Gettysburg’s treasures and to provide the public with high-quality interpretation of the Gettysburg campaign and its consequences has always motivated him. Some critics, he said, “are not going to be happy until I am dismissed from this position in disgrace. It’s unfortunate that it has sunk to that level.”

Lightning Rod

The massive museum-visitor center, with its fieldstone building and barn-like structure, was designed to look like a big Pennsylvania farm. It is about a half mile south of, and below, the old visitor center that sits on historic Cemetery Ridge. Inside the new facility is a large lobby; 11 exhibit galleries, based on phrases from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address; two theaters for viewing a 22-minute film, A New Birth of Freedom, narrated by actor Morgan Freeman; storage for artifacts; a library and reading room; a restaurant; and a book and gift shop. The center also houses the magnificent oil painting-in-the-round, known as the Cyclorama, which depicts “Pickett’s Charge” — Confederate Gen. George Pickett’s doomed advance on Cemetery Ridge that led to Lee’s crushing defeat. The restored painting measures 42 feet by 377 feet.

Under the Park Service’s agreement with the Gettysburg Foundation, the nonprofit owns the facility and receives significant revenues from its operations. Those revenues include some of the proceeds from the book and gift shop and a restaurant run by separate for-profit companies. The foundation also takes in all revenues from admission sales. The nonprofit must pay the operating and maintenance costs for the center — an arrangement, Latschar says, that saves the Park Service $300,000 annually — and retire $15 million in long-term debt. The agreement requires the foundation to donate the museum-visitor center and the land it sits on to the Park Service in 2028.

Initially known as the Gettysburg National Battlefield Museum Foundation, the nonprofit has had some esteemed board members; in the past decade they have included prominent Civil War historians and business leaders. Dick Thornburgh, the former Republican governor of Pennsylvania and later U.S. attorney general, continues to serve on the board.

From the beginning, more than a decade ago, critics of the partnership arrangement viewed it as a profit-making scheme for private interests. Robert Kinsley, a major construction contractor from York, Pa., put the foundation together after the Park Service selected him to develop the museum-visitor center.

Kinsley and Latschar are close. Indeed, as chairman of the foundation, Kinsley asked Latschar to take over as the nonprofit’s president last year, only to be disappointed when ethics questions forced Latschar to step aside. Like Latschar, Kinsley has been a lightning rod for criticism: Critics say he profited from Gettysburg Foundation work on the museum-visitor center, a charge he strenuously denied in an interview with National Journal.

Kinsley, chairman and CEO of Kinsley Construction, has repeatedly said that philanthropy, not profit, has motivated him. The chairman of the Gettysburg Foundation since its inception, Kinsley has donated nearly $8.4 million to the nonprofit through his family foundation, his personal funds, and Kinsley-owned partnerships, according to foundation officials. The gifts have included cash, forgiven loans, and donated real estate. The contributions, the officials say, make Kinsley the largest private donor to the project; the next-biggest donor gave $4.5 million.

At the same time, Kinsley’s construction company and another family-owned company, LSC Design, worked on the development of the museum-visitor center. The foundation’s decision to use the Kinsley companies, Latschar said, was approved by Park Service officials in Washington.

According to the Gettysburg Foundation, it has paid the companies a total of $8,509,825 for their work on the project. The foundation said that Kinsley Construction was “reimbursed” $1,332,550 for supplying equipment, drawings, supplies, and other items to the project. It paid another $3,461,275 to Kinsley Construction for providing construction management “at cost” and at “no profit,” the foundation said. Additionally, the foundation has paid $3,716,000 to LSC Design, which is headed by one of Kinsley’s sons, Robert II. Those fees, the foundation said, covered architectural design work for the museum-visitor building and other services, including structural, traffic, and civil engineering.

The senior Kinsley acknowledges that LSC Design got the design work at his suggestion. He said he suggested that the board hire LSC Design when he realized that the foundation could save money by using the firm run by his son. After foundation lawyers and the Park Service signed off on the arrangement, Kinsley said, the board gave its approval. Kinsley said he recused himself from all board discussions on the issue. Moreover, foundation officials said that an auditing firm, independent of Kinsley, is reviewing his companies’ charges.

Apart from the museum project, Kinsley’s construction company has worked as a major subcontractor on two contracts awarded by the Park Service in 2007 to a New Jersey company, Puente Construction Enterprises. Puente, a minority contractor under a U.S. Small Business Administration program, was hired to repave 19 historic roads, repair a bridge, and replace deteriorating water lines in the Gettysburg park.

The Puente contracts were worth nearly $4.1 million. The minority firm paid Kinsley Construction $2.5 million as the principal subcontractor on the park work, according to Barbara Sardella, general counsel for the Kinsley firm. In the interview, Kinsley said that his company’s work as a subcontractor “has nothing to do with the museum.” Both he and Latschar said that the park superintendent played no role whatsoever in his firm’s getting the work.

As for the foundation payments to his companies on the museum project, Kinsley said he was not profiting from the arrangement. “I made a promise when I went to Gettysburg that I would not profit from this or anything else in Gettysburg because of this,” Kinsley said. “I am very happy I have been able to contribute to Gettysburg the way I have. I just wish [critics] would do the same.”

The Price Of Preservation

Kinsley and park officials said that the ambitious museum project allowed them to convey to the public much more clearly the Gettysburg story and the battle’s consequences. The old facility, they said, did not do justice to the historical importance and emotional power of Gettysburg. “We only had one chance to do this,” Latschar explained, “and we wanted to do it right, as befits this hallowed ground.”

Even at its original cost estimate of $39.3 million in 2001, the Gettysburg project was the most expensive Park Service visitor center in the works. The Government Accountability Office reviewed 80 visitor center projects under construction or renovation and found that the “average cost to build a visitor project was $6.7 million.” But Gettysburg Foundation officials say that the report is misleading when applied to their project. “If you just looked at our visitor center piece of it, it’s probably not much more than that,” the foundation’s president, Robert C. Wilburn, told National Journal. “The real expensive part is the museum and the Cyclorama [painting]. We spent $15 million on the [restoration of] the Cyclorama painting alone.”

The Cyclorama is a historical icon painted in the 1880s by French master Paul Philippoteaux and a team of artists and is considered central to the park’s story line. The painting’s restoration is a prime example of why the cost of the project increased so dramatically — and why federal funds ended up in the mix. Back in 1997, the restoration was projected to cost $5 million. By 2002, the estimate had jumped to $6.6 million. By the time the restoration was completed and the painting was moved to the new museum-visitor center from the old facility, the cost had skyrocketed to $15 million — all paid for with congressional earmarks arranged by Rep. Murtha.

Other increases came from the cost of construction, design services, fundraising, exhibits, and landscape restoration. The foundation also expanded its role in the park. It merged with another foundation, which had long supported the park, and it recently spent $1.9 million to acquire an 80-acre farm, “protecting the historically significant site from private development, according to a foundation press release.

Wilburn, who formerly served as president and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, makes no apologies for the cost, or the size, of the Gettysburg center. “What I have said before,” he explained during an interview in his second-floor offices in the center, “is that I regret that we weren’t able to raise money to make it even better.” Wilburn went on, “The restaurant is too small for the summer, the gift shop gets jammed… it is not oversized.” Most visitors and professional reviewers have given the new center a big thumbs-up.

Wilburn also defended the decision to charge visitors an “all-in-one” fee of $7.50 to see the museum artifacts and exhibits, along with viewing the Cyclorama painting and A New Birth of Freedom. The foundation, he said, had planned to keep the museum free and charge a $12 fee to see the painting and film. But shortly after opening the center, he said, foundation officials and the Park Service realized that revenues couldn’t cover expenses. “We have had almost no negative comments about it,” he said. “People seem to think it’s a real bargain.”

That’s a difficult argument to make to descendants of Gettysburg resident John Rosensteel who, at the age of 16 in July 1863, began collecting artifacts from the battlefield just days after the guns fell silent.

Over the years, the Rosensteel family acquired Gettysburg and Civil War artifacts. The 38,000-piece collection, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, was donated to the government in 1971 by George and Emily Rosensteel. Pamela Jones, their grandchild and a resident of Gettysburg, said that the park should never have implemented a fee to see the artifacts. “The gift was made to the American people,” she said in an interview, “in the hope that the artifacts would always be viewed for free.” The collection includes the saddle cover used by President Lincoln when he rode on horseback from the town of Gettysburg to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, as well rifles, cannons, drums, uniforms, maps, photographs, and paintings.

According to Latschar, the old visitor center, which was built by George Rosensteel in 1920, will soon meet the wrecking ball, and demolition plans are also in the works for the cylindrical building that used to house the Cyclorama painting. But a group that favors preserving significant modern architecture is attempting in a federal lawsuit to block the demolition. The Cyclorama building was designed by the late modernist architect Richard Neutra, whose son, Dion, is a plaintiff in the case. Both buildings sit on Cemetery Ridge, one of the most historically significant battlefield sites in the park. The plan is restore the landscape to its 1863 appearance.

Speaking His Mind

Latschar operates the park on a relatively small budget. Along with the adjacent Eisenhower National Historic Site, the home of the late President Eisenhower, he has about $7.6 million annually to work with. In one four-year period, though, Congress gave him some extra money — $1.1 million over a four-year period — to help with historic landscape rehabilitation.

Latschar’s superintendent’s reports provide details on the park’s operations and funding — and a forum he uses to speak his mind. He made the reports available to National Journal, explaining that they were “a long-cherished tradition in the Park Service.” Latschar went on: “Historians start there. By tradition, it is the one report where the superintendent can say exactly what he thinks is important to put on the record. Nobody can change it. A copy goes straight to the National Archives.”

The reports offer frank assessments of some critics, even the few who emerged occasionally in Congress. In his 1999 report, Latschar suggests that then-Rep. Ron Klink, a Democrat who opposed the museum project, was nothing but a political opportunist. He wrote that Klink, who was running for the Senate against the incumbent, Rick Santorum, “was virtually unknown in the central part of the state”‘ and “apparently decided that he needed a ‘name recognition’ issue.”

At the same time, Latschar heaped praise in his reports on Santorum, a big supporter of the project, once even describing the Republican as a “hero.” Latschar wasn’t too happy, though, when the GAO reviewed the partnership arrangement in 2001. He wrote that the GAO “seemed obsessed with what the partner [Kinsley] gets out of the partnership,” adding: “When told ‘nothing but the good feeling of making a difference,’ they were obviously unconvinced, a sad indication that philanthropy is not well understood inside the Washington Beltway.”

Latschar describes how Murtha repeatedly arranged for earmarks to fund the Cyclorama restoration, and details the historic landscape rehabilitation at the park, including the removal of “nonhistoric” woods, the replanting of orchards, the construction of a historic fence, and the removal of a “major nonhistoric structure” that once housed an automobile dealership.

He doesn’t let roadblocks stand in his way. Witness his dispute with the construction management staff of the Park Service’s Development Advisory Board over the comprehensive design for the museum-visitor project. In the end, Latschar prevailed, but had he failed at the DAB level, the project could not have gone forward without being scaled back; the board must review and sign off on all major construction projects.

Latschar, in an annual report, described what happened: “Showing a human foible… all too common, the staff of the DAB seemed overly concerned that the Museum Foundation was building too large a complex and spending too much money, even though the Foundation was taking all the risks, and the [National Park Service] was taking none.” In October 2003, he wrote, “we had a highly unsatisfactory call with the Washington Office construction management staff. The staff of the Museum Foundation was insulted by the unprofessional treatment and skepticism they received from the NPS staff. I was embarrassed.”

Latschar contacted a senior Park Service official who arranged for a meeting between the foundation and Fran Mainella, then the director of the Park Service. “The Director apologized to the Foundation,” Latschar wrote, “and promised to be personally present at the Foundation’s presentation to the Development Advisory Board on November 4, 2003.”

Mainella, Latschar, and the DAB and some of its staff members attended that subsequent meeting in Washington. According to Latschar’s report, “Rob Kinsley, the project architect, presented a superb power-point presentation” detailing how the design was developed. “There were relatively few questions asked, and none with any merit,” Latschar wrote. “In the end, the project was approved.”

Latschar makes no apologies for going over the heads of the DAB’s staff. He told National Journal that Mainella “reprimanded” the staffers for insulting the Kinsleys and others involved in the project.History As Judge

Now, with Interior’s IG reviewing the Gettysburg partnership and the museum-visitor center project, Latschar, at least outwardly, exudes an air of confidence. He said he was recently questioned by investigators who had “just swept up” every allegation “and decided it made sense to ask the questions.” They mostly wanted to know about “the birth and evolution and the maturation of the partnership.” The investigators asked him, he said, about the Gettysburg Foundation’s use of companies affiliated with the senior Kinsley, the foundation’s chairman, and “a few other odds and ends.”

Latschar acknowledged that investigators are also exploring whether he had misused park and nonprofit funds to replace a wire fence around 4 acres of park land at the back of his 2-acre home. His wife uses the pasture for her two adult horses and a yearling under a “special-use permit” issued by the park. The Park Service replaced three sections of the fence in 2002; it replaced another section late last year. The total cost was $8,700.

Under the park’s “agricultural lease program,” Latschar said, Terry Latschar pays $75 a year for the permit, which he said was consistent with similar arrangements in the park. His wife first obtained the permit in August 1999, or two years before the couple was married. Under the arrangement, John Latschar said, she is responsible for maintaining the park pasture and repairing the wire fence. “But when it comes time that the fence is beyond repair and needs to be replaced,” he said, the permit requires the Park Service to replace the fence. “That’s the Park Service responsibility,” he explained.

Indeed, the permit does require her to maintain the fence but it does not contain a clause requiring the park to replace the fence. When asked about this in a later interview, Latschar acknowledged that there’s nothing in his wife’s permit requiring the park to replace the wire fence. Nonetheless, he said, the “practice” of the park has been to replace deteriorated fencing in such cases. In a follow-up e-mail, he cited other instances in which the park had replaced fencing on parkland used by other permit holders. The park, Latschar said, acts under broad authority to “preserve resources and, or, protect visitors.”

The park spent $3,910 to replace “505 feet of No Climb Horse Fence” last year, according to the contract with the contractor who did the job. An explanation from the park’s maintenance division says that “the fence is an emergency replacement as a very large section of the fence has been destroyed from a horse being entangled in the fence.”

Earlier, in March 2002, Latschar used funds from a nonprofit to replace 1,126 feet of the pasture fence. The $4,800 job was billed to Eastern National, a nonprofit that operated the bookstore in the old visitor center and provided funds for preserving the park. The purchase order includes Latschar’s note that the new fencing will “prevent livestock from getting out in the vicinity of Sedgwick equestrian monument.”

Latschar said he did not “pressure” the park’s maintenance chief to replace the fencing and there was “not a frigging chance” that he had acted improperly.

Even today, 146 years after Americans spilled blood on this hilly farm country, controversy at Gettysburg never seems more than a musket shot away. And John Latschar, a man whose self-confidence and take-no-prisoners style brings to mind the brash generals of the armies that clashed here, is convinced that history will treat him well.

Asked to list his accomplishments, he ticks off the removal of the National Tower, the landscape restoration program, and the partnerships formed with the Gettysburg Foundation and local townspeople. His legacy, Latschar is convinced, is to have helped preserve a transcendent moment in the nation’s past and literally enshrine the battle in its rightful place as a turning point in the Civil War.

However his tenure at Gettysburg concludes, Latschar clearly doesn’t mind being on the hot seat. But like everything connected to Gettysburg and the Civil War, the debate over actions, consequences, and meaning never comes to an end.

Something continues to smell bad about all of this…..

Scridb filterI’ve been a student of the Battle of Gettysburg for about 40 years. I have seen a lot of strange and even bizarre things about the battle, and I’ve met a lot of people who share my fascination with it. I have even met a few who had an overarching, Gettysburg-only focus, to the exclusion of all other aspects of the Civil War, which is something I just have never understood.

However, I have never seen anyone with a dedication to the Battle of Gettysburg like Dennis Morris. Visit his website. But prepare to be blown away before you do. I’ve never seen anything that reflects dedication to the Battle of Gettysburg that comes close to holding a candle to Dennis’ work….

Check it out.

Scridb filterWow…what a long day….

We just got home from a whirlwind trip to Virginia for a speech to the Louisa County Historical Society on the Battle of Trevilian Station. It’s about 450 miles from my house to Louisa, so it’s not exactly around the corner.

We left on Friday afternoon, 2.5 hours later than I had wanted or planned to leave. It meant that we had to make most of the trip in the dark, and much of it in pretty heavy snow. It started snowing while we were still in Ohio and continued snowing the whole way through West Virginia, only quitting about the time we crossed from West Virginia into Virginia. We didn’t get to Louisa until 11:00 after a tough trip. There were places and times where it was almost whiteout conditions coming through the mountains of West Virginia between Charleston and Beckley.

Louisa is a small town and there’s only one motel. It’s kind of seedy, so we stayed at a bed and breakfast where we’d stayed previously. The place has changed hands since then. The woman who now owns it as nice as can be, and makes a mean breakfast. However, she’s completely re-decorated the place. It went from understated and fairly plain to stuffed to the brim. As just one example, there must have been 100 or so Boyd’s Bears and beanie babies in our room, and they were only a small percentage of the total amount of junk filling the room. It was so incredibly crowded that I was genuinely afraid I would knock something over every time I turned. I had to move a bunch of stuff just to clear a place to put my keys, wallet, watch, etc. There was so much junk in this room that it was actually stressful, so much so that I cannot ever envision myself staying there again.

The talk went well. I had about 40 for the talk, and signed a bunch of books. From there, we drove to Fredericksburg to meet old friend Melissa Delcour and her beau for lunch. I had two choices of routes from Louisa to Fredericksburg. One is shorter but requires the driver to spend about 15 miles on Route 3. The other is longer, but misses Route 3 altogether. I opted for the Route 3 choice, meaning that we passed through a whole series of battlefields along the way: Verdiersville (where Stuart was nearly captured and lost his plumed hat in August 1862), Mine Run/Locust Grove, the Wilderness, Chancellorsville/Salem Church, and finally Fredericksburg. We also passed the spot where WalMart wants to build its new blight–sorry I mean superstore. Route 3 is a traffic nightmare, especially on a Saturday twelve days before Christmas. The construction of the WalMart will only extend the traffic nightmare farther west to Orange County.

After fighting our way through the traffic nightmare, we had a spectacular lunch at a place called Bistro Bethem, and then visited a nearby wine store. We then wandered over to the visitor center on Marye’s Heights and arrived in time to visit with Frank O’Reilly while he and his colleagues were placing luminaria for the evening commemoration of the 146th anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg.

I’m used to the ridiculous crowds that infest Gettysburg on the anniversary of the battle, so I was surprised that the crowds in Fredericksburg were much smaller than what I expected. We saw a few farby Confederate reenactors wandering around downtown, and one fairly large tour group on Marye’s Heights, but, other than many more cars than usual, it didn’t really seem like a special occasion. But for the luminaria, in fact, it probably wouldn’t have seemed any different than any other day.

Last night, the Trevilian Station Battlefield Foundation threw an invitation-only dinner in my honor. The incoming president of the TSBF, Kathy Sheridan-Stiles (a direct descendant of an uncle of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan), owns a lovely old home and private party facility called Early House. Kathy hosted the dinner last night, and a good time was had by all.

Today, we got up extra early, as Susan wanted to do a little shopping in Leesburg on the way home. That meant we had to drive 90 miles to get there, passing right through the Brandy Station battlefield along the way. We arrived in Leesburg, got the things Susan wanted, and then headed for home. We covered about 1000 miles in 48 hours, drove by or past a whole bunch of major battlefields, and finally got home about 6:30, just in time to pick up the dogs at the place where we board them.

It was a whirlwind of activity. It was a lot packed into a very short period of time, but it was worth the trip. But, boy, what a whirlwind of activity, and I got to be in Fredericksburg–even just for a couple of hours–on the anniversary of the battle, which is something I’ve never done before. On top of all of it, I have two very intense days coming up tomorrow and Tuesday….

Thank heavens my Civil War travels are at an end for about 90 days or so. I really need the rest.

Scridb filterFrom today’s issue of the Chester, VA Village News:

Historical Park Soon to Close Doors to Public

Dec 3, 2008 – 12:32:55 PM

Effective January 2, 2009, Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier in Dinwiddie County will be open by reservation only. Guests wishing to visit the Park may do so by making a reservation forty-eight hours in advance. Admission fees for non-members will be $100 for a group of up to ten people, and $10 per adult for groups of more than ten. Park members may make reservations twenty-four hours in advance with no minimum numbers and no admission fee.

The Park will continue to offer all reservation-based programming as usual, including its popular school field trips, battlefield tours, Annual Symposium, Civil War Adventure Camps, Summer Teacher Institutes, and History Day Camps.

“The severe economic downturn has undercut the ability of the Pamplin Foundation to support the Park at current levels,†says Pamplin Historical Park President, A. Wilson Greene. “We deeply regret the necessity to curtail normal daily operations to meet this new fiscal reality.â€

None of the Park’s four museums will be altered and the Park will continue to maintain its four historic structures, ten reconstructed buildings, and three miles of interpretive trails. There will be no changes to the Park’s extensive artifact collection. “Should economic conditions improve, we hope to restore some regular public operating hours next spring,†adds Greene.

The Park will continue to accelerate its use of the internet to fulfill its educational mission through on-line programming. Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier preserves 422 acres near Petersburg, Virginia, including the Breakthrough Battlefield, a National Historic Landmark. It is owned and operated by the Pamplin Foundation of Portland, Oregon. The Park opened in 1994 as Pamplin Park Civil War Site and debuted the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier in 1999, when it adopted its current name.

Pamplin Park, which is funded by the Pamplin Family Foundation (the Pamplins are the majority shareholders of the company that owns and operates Boise Pacific), has, for more than a decade, been the model of an upscale Civil War battlefield with a state-of-the-art museum and an excellent bookstore. The park features the spot where Union troops broke Robert E. Lee’s lines at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, meaning it includes some critical ground. It always made its neighbor, the Petersburg National Battlefield, look like its poor red-headed stepchild little brother.

Now, even Pamplin Park is suffering as a consequence of the economy, which is tragic. The Petersburg Campaign, which gets little enough attention from historians and the public, will get even less attention now that Pamplin Park will no longer be available to the public on a regular basis. And that’s a tragedy.

Scridb filterThree of my friends, including Mike Peters, from our CWRT, and I spent the day touring the battlefield at Perryville yesterday. I’d only been there once before, in 1994 or 1995, and Mike likewise had only been there once before. Tim was making his first visit, while Rory, our fourth, has been there multiple times. As you will see from the photographs, it was an absolutely magnificent day–lots of sun, blue skies, no humidity, gentle breezes, and about 80 degree temperatures. One could not have asked for any better weather for battlefield stomping.

The last time that I was there, there was only a fraction of the interpretation that’s present now, and thanks to the efforts of the CWPT, lots of land has been added to the park. It is important to note that the battlefield is a Kentucky state park, NOT a national park. Nevertheless, it’s gorgeous, mostly pristine, and has tons of interpretive markers and trails. There are, in fact, more interpretive markers on this battlefield than there are on a lot of the national parks, and I was really impressed by it.

Imagine a battlefield as rural and pristine as Antietam, about the same size, only without all of the monumentation that marks Antietam, and you have Perryville. The battlefield is narrow and very compact; there are places where opposing batteries were blasting away at each other from within cannister range. The battle was one for ridge line after ridge line; the ground undulates and is marked by one ridge after another.

There’s also a nice little visitor center with a decent selection of Western Theater books and some other trinkets (I added another pin to the collection on my CWPT hat), and a small museum with some well-presented exhibits.

We were fortunate enough to have a couple of West Point alums who are retired Regular Army officers with us for a a couple of hours, meaning we were able to get onto some private property and see some sites associated with the battle that we otherwise would not have seen, including the site where Sheridan disobeyed orders and brought on the battle. That was extremely helpful to helping us to understand how things proceeded once fighting broke out.

We easily walked 8 or 9 miles over some extremely hilly, undulating terrain. It was tiring, but we saw pretty much the entire battlefield. I came away from it with a much better understanding of this battle and how it developed and played out. I am going to re-read Ken Noe’s excellent history of the battle, and then I should really have a solid understanding of it.

This beautiful battlefield, with its gorgeous hills and dales and lovely views, could easily and rapidly become one of my very favorites. You can also easily see the entire battlefield in a single day, which is nice. It’s compact and accessible, and I highly recommend a visit.

A lovely view from Peters Hill, which was Phil Sheridan’s headquarters during the battle. The view in the distance is of the main battlefield. This is the position from where Sheridan gave the orders that brought on a general engagement in violation of his orders.

Our group, at Parsons’ Battery. From left to right: Tim Maurice, Mike Peters, Rory McIntyre, Clair Conzelman, Tasha Conzelman, and yours truly.

Starkweather’s Hill, from Parsons Battery. This was the highest point on the Union line, a position from which the Union troops were driven.

The monument to the Union soldiers on the battlefield near the Confederate cemetery.

The Union order of battle monument.

The monument in the Confederate cemetery. This is a mass grave with only two specific soldiers identified with their own headstones. The rest are apparently unidentified.

The Dye house, which served as Simon Bolivar Buckner’s headquarters during the battle.

Looking down on the Squire Bottom house from the main Union line.

A full shot of the Squire Bottom house. Bottom lost everything as a result of the day when the war visited his property.

This is a recent addition to the battlefield honoring Michigan’s contributions to the Battle of Perryville. It overlooks the Squire Bottom house.

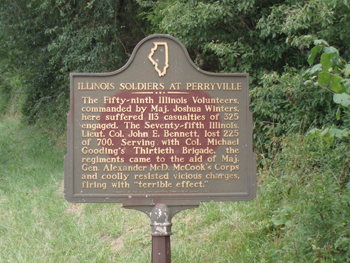

A similar marker honoring Illinois’ contributions to the Battle of Perryville. This is located very near the final Union line, at the Dixville Crossroads.

We encountered this cheeky llama at the end of the day, near the position that marked the final Union line of battle near the Davidson house. We determined that he is the sole surviving member of the 143rd Peruvian Llama Cavalry. 🙂

Scridb filterThe following review of the new visitor center at Gettysburg by publisher Pete Jorgensen appeared in the most recent issue of the Civil War News:

The new Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park is not a museum at all and it has little on display regarding the battles of July 1, 2 and 3 in 1863.

It is a massive, attractively designed structure with vast amounts of exhibit space devoted not to exhibits, but to presentations. It also has a large gift shop operated by Event Network, a for-profit cultural attraction retailer.

The museum/visitor center is owned by a private, non-profit foundation which has engaged the National Park Service as groundskeepers, guides and guardians of the country’s largest collection of Civil War artifacts, which are stored away, far out of the visitor’s view.

Just before the “museum” opened, Gettysburg National Park Superintendent John Latschar tried to excuse the lack of exhibits and the identification of artifacts by saying of the old visitor center, “What we’ve got here right now is what is known as a collections museum. We’ve got rows and rows of rifles and pistols and cases full of battle debris, and zero story.”

He explained, “What we’re creating is a storyline museum, where you use artifacts to illustrate the storyline. So we have no need for 40 varieties of rifle muskets. We’re trying to provide our visitors with a basic understanding of the battle of Gettysburg in the context of the war and in the context of America….”

For 10 years people who have been involved in this project argued that the reason for building a new museum was that they had storage rooms full of more than 38,000 artifacts from the famous Rosensteel Collection and no room to display them.

Now that they have the room, they still have no interest in displaying them. We’d call this “museum fraud.”

This collection was started by John Rosensteel of Gettysburg who was age 16 in July 1863. In the 1890s he opened the Round Top Museum to display his collection to visitors. He expanded his collection by purchasing others and bought from local residents who had barns full of stuff from the battlefield.

In 1921, his nephew George Rosensteel opened the Gettysburg National Museum on land purchased from his uncle and continued buying up other Civil War artifact collections. His museum remained in private hands until 1971 when it was donated to the National Park Service.

At the former visitor center — the Rosensteel museum building — the Park Service displayed 6,633 artifacts from the Rosensteel collection. In April, when the new visitor center opened, only 1,338 artifacts were put on display, according to a Park Service news release.

That’s 79.8 percent fewer objects now exhibited than during the 37 years the Park Service has been responsible for the collection. It’s only 3.5 percent of the total artifacts locked away in storage.

We don’t even have to go to the definition of what the word “is” really “is” to unravel this outright fraud. Just pick up the dictionary — any dictionary — and look up the definition of the word “museum.”

You won’t find any definition for a “storyline museum,” nor will you find that a museum is “a place where stories are told.” No. That’s under “theater.”

The universally recognized arbiter of the language is the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary. It states: museum.n, A building or institution in which objects of historical, scientific, artistic, or cultural interest are preserved and exhibited. Also: the collection of objects held by such an institution. ?

There is no secondary definition of the word “museum.”

Gettysburg park officials apparently don’t know or don’t care what a museum is or what the general public expects to find in a museum. They built a “theater” to tell a “storyline” and now are trying to convince us that it is a new kind of museum that people who write dictionaries don’t know about yet.

Since this so-called museum isn’t designed to exhibit the 38,000 plus artifacts in storage at Gettysburg National Park, why keep them hidden? Why keep them at all? Let’s have an auction so that the people who value these objects can acquire them at market price.

What purpose is served by locking up thousands and thousands of Civil War muskets, rifles, carbines, shells, belt plates, uniforms, buttons, and all sorts of other stuff? Always the excuse has been “we don’t have the room to display it.” But now that they have the room, they won’t display it and we doubt many in the Gettysburg Park management can correctly identify any five objects in the collection selected at random.

That’s their problem, but it is our problem too. It’s a problem for the American taxpayer and the public in general. It’s a problem for the thousands of school kids who visit Gettysburg each year and the tens of thousands of visitors who think they will see some of the old guns, uniforms, bullets, cannon projectiles and other artifacts left behind after the battle. These are the things they expect to find in a museum.

We suspect park managers don’t know what they have, so they don’t know what is important to put on display and what is not.

For example, Gettysburg National Military Park has the best collection of Confederate 12-pounder bronze Napoleon cannon in the country. But not a single Confederate bronze Napoleon is on display in the “museum.”

All the Union 12-pounder Napoleon cannon look the same from a distance, regardless of maker, as all were made to a set of standard specifications. But there are five types of bronze Confederate Napoleons, all with distinct profiles.

On the field at Gettysburg you can pick out a Macon Arsenal Napoleon from 200 yards away, but you have to get closer to positively identify many others. Confederate Napoleons were made at Augusta Arsenal, Macon Arsenal and Columbus Arsenal in Georgia. And at the Tredegar Foundry in Richmond, Va., at Leeds & Company in New Orleans, at Quinby & Robinson Foundry in Tennessee and at a small cannon works in Charleston, S.C.

All of these represent different scientific and historical views on cannon design and economy of materials in the 19th century. That’s stuff you go to a museum to study and see first hand.

The first case in the museum’s display area contains a mixture of 26 Union and Confederate field artillery projectiles. None are identified. You’d never know which ones were used by which side or that each one actually does have a name, type and size associated with it.

Shells, solid shot, canister rounds, case shot, rifled and smoothbore ammunition are all mixed together. To everybody except a projectile collector the case is just a pile of old iron. And that apparently includes the National Park Service museum curatorial staff.

There are four more cases with 93 artifacts identified only as Civil War Firearms. But, again, there are no individual identifications as to Union or Confederate, carbine, rifle, or musket. One of these cases has 44 “pistols,” many of which are actually revolvers, not pistols. Each, of course, had a model, maker, type name, bore size and intended use, but there is no signage to tell anybody that.

A careful review of all 93 firearms confirms that nobody on the National Park Service staff knows anything about Civil War firearms and, worse, they don’t care if you do either.

One model infantry arm was ubiquitous during the four years of war — the Model 1861 Springfield Musket. They were everywhere. They were used in every major Civil War battle, carried for four years by half the Union army and they were also fired in hundreds of skirmishes between the forces of North and South.

Springfield Armory itself turned out more than 265,000 Model 1861 rifle muskets and 21 private contractors produced another 452,000 to the same government specifications.

In total, of the 1.5-million Union infantry rifle muskets produced, 717,000 were Model 1861 Springfields.

The number on display among the 93 firearms in the Gettysburg Museum’s display lobby: Zero.

That’s right. Zero. We counted and examined the cases three times.

Zero Model 1861 rifle muskets.

It’s like a man in charge said, “Hey, Jim, go down to the basement and get some guns to fill up those display cases.” And Jim said, “Which ones do you want, John?” And the reply could have only been, “Long ones, medium ones, short ones — mix ‘em up to get a good representative sample.”

It’s not only incredible, it’s ironic.

This place claims to be the Museum and Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Military Park, and as a museum it can’t find the space to display a single example of the one model of rifle musket that was used by nearly half the Union infantry.

According to the Gettysburg Foundation’s Web site, the following was listed as the primary goal of the new building:

“Protection of the park’s collection of artifacts and archives: The park owns collections of 38,000 artifacts and 350,000 printed texts, historic photographs and other archival documents. New facilities are needed to provide appropriate storage conditions, proper care, and display of the collections.”

Well, there is no question they haven’t met their goal when it comes to the part about “display of the collections.”

Another case along the walls contains buckles, saber belt plates and buttons. There is one standard U.S. officer’s saber belt plate, one General Officer’s 3-piece wreath plate with stippled gold-leaf plating, but not a single one of the common enlisted cavalryman’s or artilleryman’s plate with a two- or three-piece silver leaf design surmounting a brass eagle.

Actually, there might be an example of the most common saber belt plate of the Union Army but it is hard to tell. In one glass case there is a field dug, tarnished and corroded belt plate that’s nearly impossible to identify. You just can’t see which applied silver leaf design it may have had, if any.

And one more — just one more — example. The oval Confederate brass enlistedman’s belt plate with a surmounted five-point star, and identified in Steve Mullinax’s book Confederate Belt Buckles & Plates on page 164 as Plate No. 299, is one of the few artifacts in the display cases with a little identification sign. It reads, “Union Militia Belt Plate” GETT #28220.

Mullinax, known for years as the country’s most informed expert on Confederate belt plates, must be wrong. The Gettysburg Museum of the American Civil War (its official name), managed by the National Park Service, apparently knows more about Confederate belt plates than the guy who wrote the book. But if Mullinax is right, that plate is worth $3,000 today and nobody will ever know it.

Just where does one go to study an exhibition of objects having scientific and historical value? All dictionaries say these objects are to be found in a “museum.” But not at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum.

There you will be charged $8 to see a film entitled “A New Birth of Freedom” that is full of its own errors, and you’ll walk through corridors with mannequins wearing reproduction uniforms, sitting on plaster horses. Then you’ll see some short film clips of the battle as you pass from room to room enjoying the “visitor experience.”

Soon, you’ll arrive at the Bookstore, Gift Shop and Refreshment Saloon, primed to open your wallet again to capture the flavor of the Civil War and perhaps your own stuffed soldier.

It is really unfortunate that those entrusted with the acquisition, conservation, study, exhibition and educational interpretation of objects having historical value have no clue as to their public responsibilities.

They are running a theater, not a museum. And they are public employees whose salaries and benefits are paid by your tax dollars.

If these new facilities were built for theater, the public should start demanding that the nation’s largest publicly owned collection of Civil War artifacts be sold — or that a museum be built to house, conserve, study, exhibit and interpret them.

Yes. A museum. Build a museum. What a novel idea.

In fairness, it should be noted that Pete visited before the identification tags were placed on the artifacts in the exhibits. They are now properly identified.

I happen to agree with Pete’s assessment of the place. I find it a real tragedy that the massive Rosensteel collection will probably never be seen in anything close to its full glory ever again. Sure, the artifacts are preserved, but so what? If nobody sees them or even knows they exist, what good are they?

All of the extraneous stuff in the museum is nice, but I would rather see the artifacts from the battle rather than a comprehensive narrative of the Civil War. Leave that to the new museum at Tredegar, or the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Instead, let’s focus the Visitor Center on Gettysburg.

Scridb filter

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like