DAVID F. DAY: MEDAL OF HONOR WINNER, FEARLESS SCOUT,

AND SELF-APPOINTED GADFLY

By: Eric J. Wittenberg©

Every now and again, a figure emerges from the obscurity of the Civil War who captures the public’s fancy. Sometimes, these figures are scoundrels. Other times, they are fearless men whose deeds of daring leave people breathless. Others perform feats of valor that leave the reader shaking his or her head, wondering where such men come from. Seldom does a single person embody all three of these interesting attributes. David F. Day, who served in Company D of the 57th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, was one of those men. This is his story.

David Frakes Day was born in Dallasburg, Ohio on March 7, 1847. He came from a farming family. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Day was only 14 years old, and had blonde hair, blue eyes, and stood only five feet, five inches tall–the boy had not even finished growing. However, his age and small stature did not deter the precocious youth, who enlisted in Company D of the 57th Ohio Infantry, which was raised in Hamilton County, Ohio, in January 1862. This regiment was organized at Camp Vance, Findlay, Ohio, on September 16, 1861. In January, 1862, just after Day’s enlistment, the regiment relocated to Camp Chase, Ohio, where it continued drilling and training for another several weeks. On February 18, the 57th Ohio received orders to report to Paducah, Kentucky, where it joined the Army of the Tennessee just in time to fight in the Battle of Shiloh. It served in the Battle of Stones River in December 1862, and in Sherman’s January 1863 Yazoo Expedition.

David Frakes Day was born in Dallasburg, Ohio on March 7, 1847. He came from a farming family. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Day was only 14 years old, and had blonde hair, blue eyes, and stood only five feet, five inches tall–the boy had not even finished growing. However, his age and small stature did not deter the precocious youth, who enlisted in Company D of the 57th Ohio Infantry, which was raised in Hamilton County, Ohio, in January 1862. This regiment was organized at Camp Vance, Findlay, Ohio, on September 16, 1861. In January, 1862, just after Day’s enlistment, the regiment relocated to Camp Chase, Ohio, where it continued drilling and training for another several weeks. On February 18, the 57th Ohio received orders to report to Paducah, Kentucky, where it joined the Army of the Tennessee just in time to fight in the Battle of Shiloh. It served in the Battle of Stones River in December 1862, and in Sherman’s January 1863 Yazoo Expedition.

That spring, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant launched his Vicksburg Campaign, which would prove to be not only of the most successful campaigns of the Civil War, but also one of the most brilliantly conceived and executed military campaigns in history. During this epic campaign, the 57th Ohio served in the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s XV Army Corps. David Day, now sixteen and with a year of service under his belt, was about to make his first mark on the Civil War.

In May 1863, Grant after failing in his first attempts to take Vicksburg, realized that a considerable force of Confederates under the command of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston was operating in his rear and might unite with Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton’s army at Vicksburg. Hoping to avoid the merging of these two armies, Grant realized that “the immediate capture of Vicksburg would save me sending for reinforcements which were so much wanted elsewhere, and would set free the army under me to drive Johnston from the State,” said Grant years later. So, Grant decided to launch an all-out assault along the siege lines at Vicksburg that later Sherman described as “the forlorn hope.”

Grant had surrounded the beleaguered city from three sides, and decided to attempt to take the stout Confederate works atop the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River in the hope of avoiding a protracted siege. Grant selected a point just to the south of one of the Southern forts atop the bluffs, which was protected by a ditch twelve feet wide and five or six feet deep, and which rose ten feet high and sloped up gently toward the enemy’s guns. The face of the fort was perpendicular, and quite steep.

The attack was to begin on at 10:00 a.m. on May 22, commencing with a furious cannonade by all of the Union artillery. Sherman’s Corps had the task of assaulting the strong Confederate works, and the Confederates had repulsed every assault. “Orders issued to all the army corps for a simultaneous attack were received. My instructions were to march by the right flank down the road before mentioned, following the First Brigade, the right of the division being led by Brigadier-General Ewing, commanding the Third Brigade, by right of rank, the position of my brigade being upon the left; a storming party of 150 men to precede,” reported Col. Thomas Kilby Smith of the 54th Ohio, who commanded Day’s brigade.

Sherman had called for 150 volunteers to serve as a storming party. These volunteers would spearhead Sherman’s assault and would prepare the way for the main attack. “As these men would be certain to draw the enemy’s fire, there was little probability of any of them returning alive, and on that account it was decided not to order any man to go, but to depend entirely on volunteers.” Each regiment was to provide its fair share of men for the assault. Due to the undue risk, none but unmarried men would be permitted the volunteer. Colonel Smith asked each of his five regiments to provide ten men. Col. A. V. Rice, the commander of the 57th Ohio, remembered that “the first man to volunteer for this hazardous undertaking was David F. Day.” These men would build a bridge over the ditch, and plant their scaling ladders against the embankment. The main body would follow behind and would use those scaling ladders to attack the fort.

On the morning of May 22, the storming party made its way through a ravine and to the Jackson Road. In the ravine waited the scaling ladders and a pile of roughly hewn logs and some piles of lumber. The advance party was to carry the logs, two men to a log, make a dash for the entrenchments, and throw the logs across the ditch to form the basis for a bridge. The second detachment would follow close up with the lumber planking, which would be thrown across the log spans. Finally, the third detachment would bring up the scaling ladders, rush across the bridge, and then plant them against the enemy works. It was truly a forlorn hope, and would lead to very heavy casualties among the courageous volunteers who would undertake the mission.

As soon as the storming party emerged from the woods, it drew heavy fire. “The gallant little band advanced at a dead run, but in the eighty rods of open ground which lay between them and the fort, about half of them were shot down.” When the survivors reached the ditch, they were unable to construct the bridges, as too many logs had been lost along the way when their bearers were shot down. “For about two hours, we had a severe and bloody battle, but at every point we were repulsed,” remembered Sherman. Pinned down by heavy fire, the storming party could not retreat. “There was nothing for it but to jump into the ditch, and seek shelter. Private Howell G. Trogden, who carried the flag of the storming party, planted it on the parapet of the fort, and dropped back into the ditch, where he kept up a fire on the Confederates whenever they attempted to reach it and take it in.”

The infantry brigades advanced, but were driven back by the heavy enemy fire, and all that reached the ditch were thirty men and four officers of the 11th Missouri, who planted their regimental colors on the embankment. A second assault launched later that afternoon met a similar conclusion, much to Sherman’s chagrin. “The Confederates finding it impossible to depress their guns sufficiently to reach them, dropped 12-pounder shells among them, but the fuses were cut too long, and consequently did not explode for about ten second. This gave the stormers time not only to get out of the way, but even to toss some of the shells back over the parapet, otherwise not a man would have survived. As it was the bottom of the ditch was strewn with mangled bodies, with heads and limbs blown off.”

When these assaults failed, the Federal infantry had no choice but to withdraw, leaving the storming party in the ditch, unable to either advance or retreat. So, they held their position and drew the fire and attention of the Confederate defenders, who loaded a gun with grape, dragged it to a position where it could enfilade the poor wretches in the ditch, and opened up on them. The storming party remained there until the survivors of the “forlorn hope” could retreat under the cover of darkness, carrying out their flags and wounded. “Of the storming party eighty-five percent were either killed or dangerously wounded, and few of them escaped without a wound of some kind.” When the attack failed, Grant ordered his army to break off and withdraw. “Thus ended the last assault on Vicksburg,” wrote Grant in his memoirs. Sherman noted, “The two several assaults made May 22d, on the lines of Vicksburg, had failed, by reason of the great strength of the position and the determined fighting of its garrison.” The city would have to be taken by siege instead.

Sixteen year old Pvt. David Day, whom his regimental commander remembered as “a most gallant and meritorious young soldier,” was conspicuous in the assault on the ditch. “In the assault he was severely wounded in the wrist, and his gun was shot from his hands,” recalled Colonel Rice. “With his bayonet he dug a hole in the Rebel works, in which he was shielded from hand-grenades, and remained there until he could return to our lines under cover of darkness.”

Eighty-one survivors of the storming party, including David F. Day, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their valor in the “forlorn hope.” More Medals of Honor were bestowed for this action than for any other single battlefield action in American history. Colonel Rice, Day’s regimental commander, wrote in 1894, “By Act of Congress medals of honor have been provided for those conspicuous for their deeds of heroism and bravery during the late war. None are more worthy and deserving this mark of honor and distinction than David F. Day, one of the survivors who volunteered for the storming party at the siege of Vicksburg.” In 1895, Day received a well-deserved Medal of Honor for “gallantry in the charge of the ‘volunteer storming party’.”

As a reward for his valor, Brig. Gen. Francis A. Blair appointed Day as an orderly on his staff in June 1863. He eventually became Blair’s chief scout, and, by the end of the war, was chief scout for the Fifteenth and Seventeenth Army Corps. He carried the moniker of “Blair’s kid scout.” In that role, Day continued chancing fate. Capt. David Ayres, who had been one of Day’s commanding officers, wrote a letter to Day’s wife. “I told her how you received your scars, how in the thick of battle you saved the captain’s life, and afterwards carried him off the field on your back, this in spite of the wound received by a Number 3 buckshot bullet, and for that act alone Major General Frank P. Blair made you chief of scouts of his division, and although you were not 17 years old you were afterward promoted to chief of scouts of the Fifteenth and Seventeenth army corps. Also how you and one other scout captured a picket post in the Atlanta Campaign by making them believe they were surrounded.”

He claimed to have been wounded in battle four times, and to have been captured three times. “I was among the first to make successful escapes from Andersonville and Florence prisons,” declared Day in his Medal of Honor application years after the war. He “escaped every time that he was captured,” declared a newspaper portrait of Day from 1905. On February 4, 1864, Day re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer, and served for the duration of the war. “I never had other than a veteran furlough,” proudly declared Day, “and never missed a fight between Shiloh and the surrender, except Jonesboro, Georgia, and then I was a prisoner in Andersonville.”

On March 10, 1865, the last major cavalry battle of Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign occurred at a place called Monroe’s Crossroads, approximately fifteen miles from Fayetteville, North Carolina. Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton, commander of the Confederate cavalry attached to Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of North Carolina, had crept up on Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry camp and had launched a savage dawn attack that swept through the sleeping camp. After being rousted from his bed and barely escaping being captured by troopers from Maj. Gen. Matthew C. Butler’s cavalry division, Kilpatrick managed to rally his troops and regain possession of this camp in a three-hour slugging match.

When Hampton grew concerned that Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s infantry was reinforcing Kilpatrick, Hampton broke off the engagement and withdrew. Kilpatrick and his horse soldiers retained possession of the battlefield at the end of the battle, but he had taken heavy losses that delayed his advance on Fayetteville for half a day. However, amused Northern infantrymen, who rushed to Little Kil’s assistance, soon dubbed this fight “Kilpatrick’s Shirt-tail Skedaddle”, much to the Federal cavalry commander’s humiliation and eternal consternation. He was determined to find a way to even the score.

On the morning of March 11, Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard, commander of the right wing of Sherman’s army, instructed Capt. William H. Duncan, the Army of the Tennessee’s chief of scouts, to gather up as many mounted men from Howard’s headquarters detachment as were available, and to scout in the direction of Fayetteville. In short order, Duncan and nearly seventy troopers, including Day, discovered an unpicketed road that led to the city. Their entrance into Fayetteville shocked the Confederate defenders, who were eager to escape. Duncan ordered part of his command to seize the bridge while the rest reconnoitered the town. “We charged into town and captured it,” recalled one of them.

After enjoying a leisurely breakfast, Hampton, and his chief scout, Hugh H. Scott, emerged from their Fayetteville hotel in time to hear shots ring out. Turning toward the sound of the gunfire, they saw some of Wheeler’s horsemen retreating down the street toward him, with blueclad cavalry hot on their heels. The burly lieutenant general borrowed a horse from a courier. “My saber was in my ambulance as I did not expect to have any use for it that morning,” he recalled. Armed only with his pistol, Hampton tried to rally some of the panicked butternuts, but Scott said to him,”General, there are not over ten or fifteen Yankees here. Give me four or five men and I will whip them right out of town.” A grinning Hampton said, “You scouts follow me, and I will lead this charge.”

Accompanied by only five men, Hampton cried, “Charge them!” The six cavalrymen dashed at the pursuing Yankees with their pistols drawn. “The eight Confederates flung themselves upon the foe, playing a lively instrumental accompaniment with their pistols to the vocal music of a splendid battle-yell,” colorfully recalled one of them.

The entire Union line blazed with fire as they delivered a volley. Although the Federals outnumbered them nearly ten to one, Hampton and his little force crashed into them. “They charged us and we had a hand-to-hand fight with them,” recalled a Federal named Collins. Scott and the Dragoons fired their pistols into the faces of their foes, knocking several from the saddle. Hampton himself blasted two Yankees from their horses, and then cut down another two with a saber that he picked up along the way.

The Federals, realizing that prudence was the better part of valor, broke off and withdrew. “They drove us back to the outskirts of the town, and we held it until our infantry came up five hours later,” noted one of Duncan’s men. The Confederates saw things differently. “The enemy broke when we struck them, we charging clear through them, and scattered to our right and left, some running towards Butler’s lines, and most of these were captured,” recalled Williams. “Hampton’s party wheeled back and kept hammering them as they fled, until all were driven out of town, or killed or captured.”

Hampton and his determined little band pursued, rounding up a dozen prisoners from the rear of the column, including Captain Duncan, the commander of the expedition, who told Hampton that he had brought sixty-eight men with him. The unidentified member of Wheeler’s command had captured Duncan when he had gotten separated from the rest of his command, and “he gave me the sword belt & pistol sheath of the captain, which I still have,” recounted Hampton in 1892. The balance of Duncan’s command galloped back to Howard’s headquarters to report their repulse.

Among the Union prisoners was David F. Day, who was dressed in a Confederate uniform. However, Day and Duncan escaped before Hampton could impose the usual punishment meted out to spies, a hangman’s noose. That night, Duncan discovered some loose boards in the floor of a closet in the house where he and Day were being held. The Federals waited for darkness and sleep to overtake their guards, and then Duncan lay down next to Day. Day told Duncan that he had removed the loose board in the closet. Duncan tried to squeeze through, but could not. He told Day that he could not do so, and also told Day that if Day could loosen the next board, but not break it, “but spring it up and stand the piece he had taken out under it to hold it up, and I would take care of the room again.”

When the fire went down, Duncan again went to the closet, when Day came through the hole in floor. The two officers dropped down through the hole, and moved stealthily from tree to tree, keeping away from the Confederate camp until they finally came to a plantation house. Some slaves told the two fugitives that they could escape via a mill-dam across the Black River. “We hurried along, not knowing much where we were going, but trusting to our deliverer.” After a day of long, hard marching, the two officers made their way back to the safety of Sherman’s army. Both served out the balance of the Carolinas Campaign, and completed their service honorably.

Hampton had intended to hang the unfortunate Day the next morning, but the spy’s timely escape saved his life. In 1891, Hampton and Day met again. “Last year when I was in Denver, he called to see me & spoke of having been in the Fayetteville fight & when I told him of the man in gray whom I had intended to hang he said that he was that man. I told him that I was glad I did not hang him, but that I certainly should have done so before his escape,” recounted Hampton in a post-war letter. A Columbia, South Carolina newspaper had a slightly different version of this meeting. “‘I had a legal right to kill you, but I am glad that I did not,’ remarked the general. ‘I am glad you did not,’ replied Dave.”

Day was honorably discharged from the volunteer service at Little Rock, Arkansas on August 14, 1865. He had served three years, seven months, and twenty-six days. He was just eighteen years old, and he was a war hero.

In the years after the war, Day moved around quite a bit. By 1879, he had married a woman named Victoria, and was living in Marshall Twp Saline, Missouri, where the census showed him as being listed as a “store Clerk”. Eventually, President Grover Cleveland appointed David F. Day Special Indian Agent for the Southern Utes, serving in the Colorado Territory. He eventually settled in Durango, Colorado, where he published an unusual and irreverent newspaper known for lampooning politicians and prominent local citizens that had the unlikely title of The Solid Muldoon, named after a Rudyard Kipling poem. The newspaper’s first issue appeared on September 5, 1879. The Solid Muldoon was one of the most strongly individualized papers of Colorado. All of the mining camps of the region had newspapers, even then, but they were mostly mean, witless sheets, subsisting mainly on legal advertising of the United States Land Office. There was little news available, and no opportunities to rpesent opinions.

“The Muldoon, therefore, burst like a fountain of sweet out of this Sahara, and there was an immediate rush for it. The scene on the afternoon of its issue was a unique and memorable one in Ouray. Copies were snatched ‘hot from the press’ and read aloud amid roars of laughter by men assembled in front of the rows of saloons that lined the main street of the camp….Its range of editorial observation covered the public men and affairs of the whole state, and its terse, incisive, nipping wit had the great merit for a newspaper of being quotable, and of course it got widely quoted. . . .The name itself was a hit. Its ridiculous incongruity with anything relating to journalism challenged curiosity. The world has probably forgotten that sometime before a party of impecunious showmen had ‘worked a fake’ on the public in imitation of the famous ‘Cardif Giant’ scheme, by ‘finding’ a petrified giant of enormous proportions in the Arkansas valley, which came to be designated the Solid Muldoon. This was the origin of the name.”

By 1900, Day was listing his profession as a “Printer, Publisher,” and had his son Stanley working with him in the business as his “Printer Foreman.” By this time, Day also had 42 different libel suits pending against him for some of the outrageous things that he wrote in his newspapers. In 1892, he had sold his interest in The Solid Muldoon to found a competing paper, The Durango Democrat. He became famous for the saying, “No man’s property or life is safe while the legislature is in session.” Day, known nationwide for his caustic wit, honesty and bitter sarcasm, proved that his pen was as mighty as his sword had been nearly thirty years earlier. His fame even spread to England, where Queen Victoria was said to have read his paper for many years.

In 1894, Day applied for a Medal of Honor. His application is both self-laudatory and self-righteous. “I deserve the medal for the reason that I have honestly won it upon more than one field, and upon more than one occasion,” he proclaimed. “I want them for my boys, as I believe every American to owe certain obligations to his country, and as I am neither a member of the Grand Army [of the Republic], or upon the pension rolls of my country, it will teach them that a grateful country sometimes (even though years between service and reward intervene) rewards those who do not parade their gallantry until recognition awaits them.” With the ringing endorsements of Colonel Rice and Bvt. Brig. Gen. Andrew Hickenlooper, a former lieutenant governor of Ohio, Day received a long-coveted and well-deserved Medal of Honor in 1895.

In a 1907 Durango Democrat article, Day railed against the granting of Medals of Honor to politicians and others who did not meet his standards for what constituted a legitimate deed of valor worthy of such decoration. A great deal of insight into Day’s personality can be gained from reading it. “Dave Day’s grandchild shall have an unclouded medal,” he declared. “It is our hobby not the verdict of coin as we have none. Not a verdict of war all patched up after near a half century, David Henry Tully’s inheritance rests upon the letters of General Andy Hickenlooper, General A. V. Rice, and others who knew every hour of it. They form a part and parcel of ‘The Records of the Rebellion.'” He concluded, “We are weary of deception, tired of presumption, disgusted with all that steals valor to promote that which individual service denies to the private.”

Day was also apparently not content with a single Medal of Honor. After receiving the Medal for Vicksburg, he tried to get a second one for his heroics at Fayetteville. “He tried several years ago to secure a medal of honor on Confederate recommendation,” noted a newspaper reporter in 1905. “Congressman Harrison, a Confederate general of Alabama, General Marcus J. Wright, commander at Macon, Georgia, and compiler of the records of the rebellion, both recommended him. He is several times mentioned in the official records of the Civil War when still under 20. When General Wade Hampton was in Denver five years before his death, Colonel Day asked for the third recommendation necessary, but failed as he got to discussing war times and he and the general had a row over the burning of Columbia, SC.” One trait of Day’s stuck out in every situation–brashness. His approaching his old nemesis, Hampton, who had intended to hang the teenaged scout, and then raising the unhappy topic of the burning of the old general’s beloved home town amply demonstrates this trait. Obviously, it cost him the coveted second Medal of Honor and probably cost him many other opportunities over the course of his life.

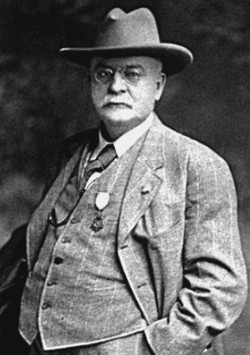

In 1905, a Colorado newspaper printed a portrait of Day, who by now was known as “Colonel Dave Day.” The promotion was apparently self-given, as there is no record of his ever being promoted beyond private during his terms of military service. The author painted a vivid portrait of a self-important war hero in his declining years. “If you see a medium sized, stoutly built man, gray eyes, iron gray mustache, with a vertically dented scar running from just below his right eye down past the corner of his mouth and a bronze medal of honor on his coat, hats off, gentlemen–that is David F. Day of Durango and that scar meant the saving of a life.”

David Day died on June 22, 1914. He was buried in Denver’s Riverside Cemetery under a simple Government-issued headstone that denotes his status as a Medal of Honor winner. Thus ended the long and fascinating life of a man who was known equally for his fearlessness, his valor, and his acid pen. His story has remained untold for far too long.

David Day died on June 22, 1914. He was buried in Denver’s Riverside Cemetery under a simple Government-issued headstone that denotes his status as a Medal of Honor winner. Thus ended the long and fascinating life of a man who was known equally for his fearlessness, his valor, and his acid pen. His story has remained untold for far too long.

Back to top

Back to top Blogs I like

Blogs I like